(Title of the Thesis)*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Sundance Film Festival Adds Four Films

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: December 14, 2016 Spencer Alcorn 310.360.1981 [email protected] BUT WAIT, THERE’S MORE! 2017 Sundance Film Festival Adds Four Films Two Documentary Premieres, Two From The Collection (L-R) Long Strange Trip, Credit: Andrew Kent; Reservoir Dogs, Courtesy of Sundance Institute; Bending The Arc, Courtesy of Sundance Institute; Desert Hearts, Courtesy of Sundance Institute. Park City, UT — Rounding out an already robust slate of new independent work, Sundance Institute adds two Documentary Premieres and two archive From The Collection films to the 2017 Sundance Film Festival. Screenings take place in Park City, Salt Lake City and at Sundance Mountain Resort January 19-29. Documentary Premieres Bending the Arc and Long Strange Trip join archive films Desert Hearts and Reservoir Dogs, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 1986 and 1992, respectively. The archive films are selections from the Sundance Institute Collection at UCLA, a joint venture between UCLA Film & Television Archive and Sundance Institute. The Collection, established in 1997, has grown to over 4,000 holdings representing nearly 2,300 titles, and is specifically devoted to the preservation of independent documentaries, narratives and short films supported by Sundance Institute, including Paris is Burning, El Mariachi, Winter’s Bone, Johnny Suede, Working Girls, Crumb, Groove, Better This World, The Oath and Paris, Texas. Titles are generously donated by individual filmmakers, distributors and studios. With these additions, the 2017 Festival will present 118 feature-length films, representing 32 countries and 37 first-time filmmakers, including 20 in competition. These films were selected from 13,782 submissions including 4,068 feature-length films and 8,985 short films. -

Louise Marwood Concludes Her Eight Year S�Nt on ITV’S Emmerdale As Chrissie White in Spectacular Fashion with a Fatal Car Crash

The Oxford School of Drama Spring 2018 news It’s been a busy start to 2018 Claire Foy was nominated for both a Golden Globe and Screen Actors’ Guild award for the 2nd year running for The Crown and is busy filming The Girl With the Dragon Ta2oo sequel; Babou Ceesay is filming the 3rd season of the US TV series Into the Badlands; Sophie Cookson is filming Red Joan directed by Trevor Nunn with Judi Dench; Annabel Scholey plays Amena in Sky’s Britannia wriKen by Jez BuKerworth; Richard Flood plays Ford, a regular character in HBO’s 8th season of Shameless. Mary Antony makes her screen debut as Mary Churchill, the youngest daughter of Winston Churchill in the acclaimed feature film The Darkest Hour which has just been released in cinemas. The Vault FesZval runs from 24 Jan - 18 March in London. It has been hailed as: “a major London fesZval … showcasing new and rising talent” The Independent The programme includes: Imogen Comrie in Strawberry Starburst Wildcat Theatre’s The Cat’s Mother Owen Jenkins in One Duck Down Arthur McBain in Nest Gemma BarneK in A Hundred Words For Snow Andrew Gower and Kiran Sonia Sawar star in the cult NeWliX series Black Mirror episode, Crocodile, alongside Andrea Riseborough. Black Mirror is a BriZsh sci fi series which eXplores the possible consequences of new technologies. Samantha Colley plays opposite Antonio Banderas in NaZonal Geographic’s series Genius about the life of Pablo Picasso. Samantha plays Dora Maar, the French photographer and painter who was also Picasso’s lover and muse. -

Peter Freeman

First Assistant Director Peter Freeman 30 Birch Grove Windsor, Berks SL4 5RT Tel : +44 (0)1753 862226 Mobile: +44 (0)7774 700 747 SA Mobile: +27 (0)76 4377 963 e-mail: [email protected] Languages: Greek, Basic French Over 12 years experience with Movie Magic Scheduling. South African ResidenceVisa. Advanced Production Safety Certificate, BBC Total Concept Safety Certificate Recent credits include: FEATURES “Gulliver’s Travels” Jack Black as Gulliver in modern retelling of classic tale. (Additional Assistant Director) Cast Inc: Jack Black, Jason Segel, Billy Connolly, Emily Blunt. Directors: Chris O’Dell (2nd Unit), UPM/1st AD: Terry Bamber (2nd Unit), “Broken Thread” Modern day ghost story. Shot in India, Isle of Man and London. Cast inc: Linus Roache, Saffron Burrows Director: Mahesh Matai Producer: Deepak Nayar A.P: Paul Sarony “These Foolish Things” Romantic comedy set in 1920’s theatre-land. Shot in and around Cheltenham. Cast inc: Angelica Huston, Lauren Bacall, Terence Stamp, Andrew Lincon. Director: Julia Taylor-Stanley Producers: Julia Taylor-Stanley, Paul Sarony “Spirit Trap” Horror/ghost story. Shot in Romania and the UK for Archangel Productions. Cast inc: Luke Mably, Sam Troughton, Emma Catherwood and Billy Piper. Director: David Smith Producer: Susie Brooks-Smith A.P: David Higginson / Cathy Lord “Chasing Liberty” Second unit Czech Republic. Cast inc: Mandy Moore, Mark Harmon Director: Andy Cadiff (main unit) Line Prod: Cathy Lord A.P: Hilary Benson “Jane Eyre” Retelling of classic tragic love story. Derbyshire & London Cast inc: William Hurt, Charlotte Gainsburg, Elle Macpherson Director: Franco Zeffirelli Producer: Dyson Lovell A.P: Ray Freeborn Page 2 “Soft Sand, Blue Sea” Film Four. -

About Endgame

IN ASSOCIATION WITH BLINDER FILMS presents in coproduction with UMEDIA in association with FÍS ÉIREANN / SCREEN IRELAND, INEVITABLE PICTURES and EPIC PICTURES GROUP THE HAUNTINGS BEGIN IN THEATERS MARCH, 2020 Written and Directed by MIKE AHERN & ENDA LOUGHMAN Starring Maeve Higgins, Barry Ward, Risteárd Cooper, Jamie Beamish, Terri Chandler With Will Forte And Claudia O’Doherty 93 min. – Ireland / Belgium – MPAA Rating: R WEBSITE: www.CrankedUpFilms.com/ExtraOrdinary / http://rosesdrivingschool.com/ SOCIAL MEDIA: Facebook - Twitter - Instagram HASHTAG: #ExtraOrdinary #ChristianWinterComeback #CosmicWoman #EverydayHauntings STILLS/NOTES: Link TRAILER: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x1TvL5ZL6Sc For additional information please contact: New York: Leigh Wolfson: [email protected]: 212.373.6149 Nina Baron: [email protected] – 212.272.6150 Los Angeles: Margaret Gordon: [email protected] – 310.854.4726 Emily Maroon – [email protected] – 310.854.3289 Field: Sara Blue - [email protected] - 303-955-8854 1 LOGLINE Rose, a mostly sweet & mostly lonely Irish small-town driving instructor, must use her supernatural talents to save the daughter of Martin (also mostly sweet & lonely) from a washed-up rock star who is using her in a Satanic pact to reignite his fame. SHORT SYNOPSIS Rose, a sweet, lonely driving instructor in rural Ireland, is gifted with supernatural abilities. Rose has a love/hate relationship with her ‘talents’ & tries to ignore the constant spirit related requests from locals - to exorcise possessed rubbish bins or haunted gravel. But! Christian Winter, a washed up, one-hit-wonder rock star, has made a pact with the devil for a return to greatness! He puts a spell on a local teenager- making her levitate. -

![Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4839/sexuality-is-fluid-1-a-close-reading-of-the-first-two-seasons-of-the-series-analysing-them-from-the-perspectives-of-both-feminist-theory-and-queer-theory-264839.webp)

Sexuality Is Fluid''[1] a Close Reading of the First Two Seasons of the Series, Analysing Them from the Perspectives of Both Feminist Theory and Queer Theory

''Sexuality is fluid''[1] a close reading of the first two seasons of the series, analysing them from the perspectives of both feminist theory and queer theory. It or is it? An analysis of television's The L Word from the demonstrates that even though the series deconstructs the perspectives of gender and sexuality normative boundaries of both gender and sexuality, it can also be said to maintain the ideals of a heteronormative society. The [1]Niina Kuorikoski argument is explored by paying attention to several aspects of the series. These include the series' advertising both in Finland and the ("Seksualność jest płynna" - czy rzeczywiście? Analiza United States and the normative femininity of the lesbian telewizyjnego "The L Word" z perspektywy płci i seksualności) characters. In addition, the article aims to highlight the manner in which the series depicts certain characters which can be said to STRESZCZENIE : Amerykański serial telewizyjny The L Word stretch the normative boundaries of gender and sexuality. Through (USA, emitowany od 2004) opowiada historię grupy lesbijek this, the article strives to give a diverse account of the series' first two i biseksualnych kobiet mieszkających w Los Angeles. Artykuł seasons and further critical discussion of The L Word and its analizuje pierwsze dwa sezony serialu z perspektywy teorii representations. feministycznej i teorii queer. Chociaż serial dekonstruuje normatywne kategorie płci kulturowej i seksualności, można ______________________ również twierdzić, że podtrzymuje on ideały heteronormatywnego The analysis in the article is grounded in feminist thinking and queer społeczeństwa. Przedstawiona argumentacja opiera się m. in. na theory. These theoretical disciplines provide it with two central analizie takich aspektów, jak promocja serialu w Finlandii i w USA concepts that are at the background of the analysis, namely those of oraz normatywna kobiecość postaci lesbijek. -

An Interview with Andrew Davies

EnterText 1.2 PETER SMITH “The Script is Looking Good”: an interview with Andrew Davies PS Before coming to talk to you, I asked my colleagues what they would most like to ask you, and more than one wanted to know how tight a brief a writer tends to be given when adapting for TV or cinema. AD Right – well, usually when I start something, it’s – first of all, it’s either going to be a one-off or it’s going to be an episode. If it’s for television and it’s going to be in episodes, usually I’m given, or we work out by mutual agreement, the number of episodes that would be best to do this kind of thing in – and when I say “we”, usually I’m working with the producer or it’s someone higher up like an executive producer. Smith: Interview with Andrew Davies 157 EnterText 1.2 For instance, I do a lot of work with the woman who’s Head of Drama at the BBC. This is one of the good things about having been around for a long time; I knew her when she was a script editor. She was a very good script editor, and I suppose what I’m working round to is there’s not usually a lot of disagreement about it. If she says “I think it would make three” or “I think it would make four” or whatever it is, I usually think she’s right. Occasionally, you find that there’s a difference, but generally people will go with what I say these days. -

George Eliot on Stage and Screen

George Eliot on Stage and Screen MARGARET HARRIS* Certain Victorian novelists have a significant 'afterlife' in stage and screen adaptations of their work: the Brontes in numerous film versions of Charlotte's Jane Eyre and of Emily's Wuthering Heights, Dickens in Lionel Bart's musical Oliver!, or the Royal Shakespeare Company's Nicholas Nickleby-and so on.l Let me give a more detailed example. My interest in adaptations of Victorian novels dates from seeing Roman Polanski's film Tess of 1979. I learned in the course of work for a piece on this adaptation of Thomas Hardy's novel Tess of the D'Urbervilles of 1891 that there had been a number of stage adaptations, including one by Hardy himself which had a successful professional production in London in 1925, as well as amateur 'out of town' productions. In Hardy's lifetime (he died in 1928), there was an opera, produced at Covent Garden in 1909; and two film versions, in 1913 and 1924; together with others since.2 Here is an index to or benchmark of the variety and frequency of adaptations of another Victorian novelist than George Eliot. It is striking that George Eliot hardly has an 'afterlife' in such mediations. The question, 'why is this so?', is perplexing to say the least, and one for which I have no satisfactory answer. The classic problem for film adaptations of novels is how to deal with narrative standpoint, focalisation, and authorial commentary, and a reflex answer might hypothesise that George Eliot's narrators pose too great a challenge. -

Marcella 3 Production Notes Low Res Final

ITV PRODUCTION NOTES *** The content of this press pack is strictly embargoed until 0001hrs on 14 January 2021 *** ** Following the TX of the first episode, the whole series will be available on ITV Hub and BritBox. Episodes will continue to air weekly on ITV main channel ** Contents Press Release 3 Interview with Amanda Burton 17-20 Foreword by Creator and Executive Producer Hans Rosenfeldt 4 Interview with Hugo Speer 21-23 Character Biographies 5-8 Episode one synopsis 25 Interview with Anna Friel 9-13 Cast and Production Credits 27-28 Interview with Ray Panthaki 14-16 Publicity Contacts 29 2 Critically acclaimed Marcella, starring Anna Friel, returns to ITV for the highly anticipated third series Innovative and gripping crime drama Marcella from leading UK independent content production company Buccaneer Media is returning to ITV. Created by internationally renowned screenwriter and novelist Hans Rosenfeldt and Nicola Larder, Marcella stars Emmy® award winner Anna Friel (Butterfly, Broken, American Odyssey) in the title role. Hugo Speer (The Musketeers, Britannia, The Full Monty) and Ray Panthaki (Away, Colette, One Crazy Thing) also return to the series whilst Amanda Burton (Waterloo Road, Silent Witness) joins the drama as the formidable matriarch of the Maguire family. Following on from the dramatic conclusion of the previous series, the eight new episodes focus upon Marcella’s new life in Belfast as an undercover detective. She has taken on the identity of Keira and has infiltrated the infamous Maguire family, but as she investigates their activities, questions come to the fore about how much she has embraced Keira’s persona and personality and left Marcella behind. -

35.Sayı Nisan.Indd

Pamukkale Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi Pamukkale University Journal of Social Sciences Institute ISSN1308-2922 EISSN2147-6985 Article Info/Makale Bilgisi √Received/Geliş:19.03.2018 √Accepted/Kabul:13.12.2018 DOİ: 10.30794/pausbed.407636 Araştırma Makalesi/ Research Article Gündüz, E. İ., (2019). "Tipping The Velvet: Specularised Sexualities in The Victorian Era", Pamukkale Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, sayı 35, Denizli, s. 83-91. TIPPING THE VELVET: SPECULARISED SEXUALITIES IN THE VICTORIAN ERA* Ela İpek GÜNDÜZ** Abstract Sarah Waters’s first novelTipping the Velvet (1998) is a neo-Victorian novel that adopts aspects of the Victorian English reality to depict the marginalised existence of lesbian lovers. In Waters’s novel, in which historical facts and imaginary notions are blurred, the homosexual female characters try to become visible and to offer an alternative lesbian history/lesbian counter- discourse to patriarchal discourse on sexuality and desire. In this article, Tipping the Velvet’s presentation of the alternative lesbian history/counter-discourse will be evaluated through the discussion of the way Waters portrays the constructions of femininity and sexual interactions of lesbian lovers in England during the Victorian period. Particularly, creating different social circles and classes among queer people in Victorian times, Waters succeeds in avoiding the stereotyping of lesbians and adds credibility to their existence. Key words: Sarah Waters, Queer, Neo-Victorian, Lesbian. TIPPING THE VELVET: VİKTORYEN DÖNEMDEKİ GÖZLEMLENMİŞ İLİŞKİLER Özet Sarah Waters’ın ilk romanı Tipping the Velvet (1998), Viktorya dönemindeki kadın hemcinslerin birbirlerine olan aşkının dışlanmış varlığını betimleyerek yeniden sunan neo-Viktoryen bir romandır. Waters’ın romanı tarihsel gerçekleri kurguladığı için, onun temsilleri, tarihsel gerçeklik ve hayal ürünü olan şeylerin bulanıklaştığı romanın gerçekliği haline gelir. -

Drama Co- Productions at the BBC and the Trade Relationship with America from the 1970S to the 1990S

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output ’Running a brothel from inside a monastery’: drama co- productions at the BBC and the trade relationship with America from the 1970s to the 1990s http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/56/ Version: Full Version Citation: Das Neves, Sheron Helena Martins (2013) ’Running a brothel from inside a monastery’: drama co-productions at the BBC and the trade relationship with America from the 1970s to the 1990s. MPhil thesis, Birkbeck, University of Lon- don. c 2013 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email BIRKBECK, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ART AND SCREEN MEDIA MPHIL VISUAL ARTS AND MEDIA ‘RUNNING A BROTHEL FROM INSIDE A MONASTERY’: DRAMA CO-PRODUCTIONS AT THE BBC AND THE TRADE RELATIONSHIP WITH AMERICA FROM THE 1970s TO THE 1990s SHERON HELENA MARTINS DAS NEVES I hereby declare that this is my own original work. August 2013 ABSTRACT From the late 1970s on, as competition intensified, British broadcasters searched for new ways to cover the escalating budgets for top-end drama. A common industry practice, overseas co-productions seems the fitting answer for most broadcasters; for the BBC, however, creating programmes that appeal to both national and international markets could mean being in conflict with its public service ethos. Paradoxes will always be at the heart of an institution that, while pressured to be profitable, also carries a deep-rooted disapproval of commercialism. -

MGEITF Prog Cover V2

Contents Welcome 02 Sponsors 04 Festival Information 09 Festival Extras 10 Free Clinics 11 Social Events 12 Channel of the Year Awards 13 Orientation Guide 14 Festival Venues 15 Friday Sessions 16 Schedule at a Glance 24 Saturday Sessions 26 Sunday Sessions 36 Fast Track and The Network 42 Executive Committee 44 Advisory Committee 45 Festival Team 46 Welcome to Edinburgh 2009 Tim Hincks is Executive Chair of the MediaGuardian Elaine Bedell is Advisory Chair of the 2009 Our opening session will be a celebration – Edinburgh International Television Festival and MediaGuardian Edinburgh International Television or perhaps, more simply, a hoot. Ant & Dec will Chief Executive of Endemol UK. He heads the Festival and Director of Entertainment and host a special edition of TV’s Got Talent, as those Festival’s Executive Committee that meets five Comedy at ITV. She, along with the Advisory who work mostly behind the scenes in television times a year and is responsible for appointing the Committee, is directly responsible for this year’s demonstrate whether they actually have got Advisory Chair of each Festival and for overall line-up of more than 50 sessions. any talent. governance of the event. When I was asked to take on the Advisory Chair One of the most contentious debates is likely Three ingredients make up a great Edinburgh role last year, the world looked a different place – to follow on Friday, about pay in television. Senior TV Festival: a stellar MacTaggart Lecture, high the sun was shining, the banks were intact, and no executives will defend their pay packages and ‘James Murdoch’s profile and influential speakers, and thought- one had really heard of Robert Peston. -

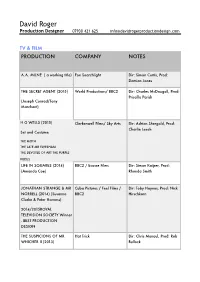

David Roger Production and Set Design CV

David Roger Production Designer 07930 421 625 [email protected] TV & FILM PRODUCTION COMPANY NOTES A.A. MILNE ( a working title) Fox Searchlight Dir: Simon Curtis, Prod: Damian Jones THE SECRET AGENT (2015) World Productions/ BBC2 Dir: Charles McDougall, Prod: Priscilla Parish (Joseph Conrad/Tony Marchant) H G WELLS (2015) Clerkenwell Films/ Sky Arts Dir: Adrian Shergold, Prod: Charlie Leech Set and Costume THE MOTH THE LATE MR ELVESHAM THE DEVOTEE OF ART THE PURPLE PILEUS LIFE IN SQUARES (2014) BBC2 / Ecosse Films Dir: Simon Kaijser, Prod: (Amanda Coe) Rhonda Smith JONATHAN STRANGE & MR Cuba Pictures / Feel Films / Dir: Toby Haynes, Prod: Nick NORRELL (2014) (Susanna BBC2 Hirschkorn Clarke & Peter Harness) 2014/2015ROYAL TELEVISION SOCIETY Winner - BEST PRODUCTION DESIGN THE SUSPICIONS OF MR Hat Trick Dir: Chris Menaul, Prod: Rob WHICHER II (2013) Bullock THE LAST WEEKEND (2012) Carnival Films Dir: Jon East, Prod: Christopher Hall GREAT EXPECTATIONS BBC Dir: Brian Kirk, Prod: George (2011) Ormond 2012 BAFTA Television Craft Awards Winner – Best Production Design 2012 EMMY Winner – Outstanding Art Direction for a Mini- series or Movie 2012 RTS Craft & Design Awards Winner – Best Production Design Drama THE SUSPICIONS OF MR Hat Trick Dir: James Hawes, Prod: WHICHER (2011) Nigel Marchant MAD DOGS (2011) Left Bank Dir: Adrian Shergold, Prod: Spencer Campbell & Andrew Benson VERA (2011) ITV Dir: Adrian Shergold, Prod: Elaine Collins MARGOT (2009) Mammoth Screen Dir: Otto Bathurst, Prod: Celia Duval ENID (2009) Carnival Films