Volume 4 Issue 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7Ulsoh Wdodt %Loo Wdeohg Lq /6 Dplg Surwhvw

$% ;# 4 "< "< < '*"'# +,-./ &! !& ) & '( *&+,-. 4 #58#%:3%9 )8#%7$=2:28>8#%5?2 -6#714:662 865%61:3-$ *5-46*51*82$7 7:5%7%417 :5%975 #%8*-* 82-7-48-87$%@87 %7##:3N*%9%2#38O 8571 5=87*@%)=$ A6 : (")&B'' &+C A 2 8 % $$ 0001,23% ,.0 8$865% gurus and practitioners, chil- dren and people from various responsible for the fiery situa- rom the United Nations backgrounds as India’s tion in the area and warned FGeneral Assembly Permanent Mission to the UN that if the TMC did not stop its (UNGA) hall to the Indian organised the commemoration dirty game to forcibly take Parliament premises and from of the 5th International Day of control of the area then Beijing to Ranchi, thousands Yoga on Friday. Bhatpara will become another of people stretched and twist- Addressing the large gath- Nandigram.” ed, breathed in and breathed ering, Deputy Secretary- The locals hurled bombs out, reached for the skies and General Amina Mohammed $% %$ 3-63# and chased away policemen bent to touch their toes as said the essence of yoga is bal- led by a Deputy India and the world marked ance, “not only within us but he fierce dogfight between Commissioner of Police who the fifth International Day of also in our relationship with Tthe BJP and the Trinamool escorted the funeral proces- Yoga on Friday. humanity.” She said by prac- Congress went on unabated in sion of the Thursday’s victims Prime Minister Narendra ticing yoga, people can pro- the Bhatpara-Jagaddal- of alleged police firing. -

London Indian Film Festival 2019 Brochure

Movies thatPack a 20-29Punch June 2019 www.londonindianfilmfestival.co.uk Artist Cary Burman. Photo by Chila Rajinder Sawhney Kumari Celebrating our 10th Birthday, the UK and Europe’s largest South Asian film festival is literally stuffed to the rafters with a rich assortment of entertaining and thought provoking independent films. This year’s highlights include a red Our Film, Power & Politics strand offers carpet opening night at Picturehouse a critical insight into the fast moving Central with the exciting World political changes of South Asia. The Premiere of cop whodunit Article 15, astonishing documentary Reason by starring Bollywood star Ayushmann Anand Patwardhan, Bangla suspense Khurrana directed by Anubhav Saturday Afternoon and Gandhian Sinha. Our closing night marks the black comedy #Gadhvi are a few return of Ritesh Batra, the director films to look out for. of The Lunchbox with the premiere We are expecting a host of special of Photograph starring the legendary guests, including India’s most famous Nawazuddin Siddiqui. indie director Anurag Kashyap of Our themed strands in this brochure Sacred Games fame, and UK Asian start with the Young Rebel strand, legend Gurinder Chadha. Make sure which literally knocks out all the you buy your tickets in advance for stereotypes with a fistful of movies these! exploring younger lives. See director We are delighted to welcome back our Rima Das’ award-winning teenage hit regular partners including Title Sponsor Bulbul Can Sing. Coming-of-age comedy the Bagri Foundation for the fifth year The Lift Boy, or Roobha and Kattumaram in a row. Thanks to the BFI Audience premieres, presenting young lives Fund and to our many friends and taking a stand. -

PG 3-6-8.Indd

SUNDAY 8 17 MARCH 2019 newstodaynet.com newstodaydaily ntchennai CHENNAI Kanaa to be KKABALIABALI ACTRESS remade in Telugu | NT BureauBu | ishwaryaishwarya RajesshRajessh whow acted in the lead in AKanaaKaK naa, will reprepriserises herh role in the Telugu re- makemake asas well.well. It hashas beenbeen titled Kowsalya Krishna- murthymuurthy - CCricketerricketer. TheThhe originalori fi lm was directed by ArunrajaArunraja KKamarajaamaraja anaandd prproduced by Sivakarthikey- PLANS PLENTY an,an, thethe TeluguTelugu remakeremakke will be directed by Bhimaneni SreenivasSreenivas RaoRao anandd prproducedod by KS Ramarao. ApartApart fromfrom Aishwarya,Aishwar the remake will have I am still writing my successuccesss RajendraRajendra Prasad,Prasad, VennelaV Kishore, Jhansi, story, says Radhikaka AAptepte Shashank,Shashank, RaRangasthalamnga Mahesh in im- portantportant roles.roles. TheT dialogues of the fi lm areare writtenwritten by KGF: Chapter 1-fame | NT Bureau | HanumanHaanuman Chowdary. The music will beb composedcomp by Dhibu Ninan Tho- adhika Apte, who became a known face in Bollywood mas,mas, who had also scored for Rpost Sriram Raghavan’s 2014 fi lm Badlapur and thethe TamilT version. The project hogged limelight playing Rajinikanth’s wifefe in Kabali, wentwen on fl oors recently. Aish- says she is still writing her success story. waryaw also has a movie The 32-year-old actor made her debut backk in 2005 with withw Vijay Deverakonda in Shahid Kapoor and Amrita Rao-starrer Vaah!h! LifeLife Ho Toh Telugu.Te Aisi! and over the years she has featured in critically-critically- acclaimed and commercially successful fifilms lms such as Parched, Phobia, Padman, Lust Stories andd Aandhdhun in Hindi. ‘I would love to work with the top stars, womenmen and men. -

The Debt to Narasimha Rao by TP Sreenivasan

OPEN 13 JULY 2020 / 50 www.openthemagazine.com VOLUME 12 ISSUE 27 12 ISSUE VOLUME 13 JULY 2020 13 JULY CONTENTS 13 JULY 2020 5 6 8 12 14 16 18 LOCOMOTIF OPEN DIARY notebook INDIAN ACCENTS TOUCHSTONE WHISPERER OPEN ESSAY Radicalisation By Swapan Dasgupta The debt to Revisiting the Pandavas The fraying of America By Jayanta Ghosal Anyone for the of the liberal Narasimha Rao By Bibek Debroy By Keerthik Sasidharan Chinese Ganesha? By S Prasannarajan By TP Sreenivasan By Sunanda K Datta-Ray 24 38 THE TRIUMPH THE POLITICS OF HEALING The extension of free food for another five AND TRIAL months promises to help not just poor OF KARAN JOHAR labourers but industry and agriculture as well Karan Johar finds By Siddharth Singh himself cast as the fall guy in the drama around Sushant Singh Rajput’s death 42 By Kaveree Bamzai BIKES AND VITAMINS Our changed lives at the peak of the pandemic By Rahul Pandita 32 32 OLD HABITS DIE HARD Demands of the modern state made nepotism a liability to be contained but even now its 46 practice in the private sphere ARE INDIAN SLAUGHTERHOUSES SAFE? is a fuzzy ethical question The rising number of Covid-19 cases in the By Madhavankutty Pillai meat industry worldwide raises concerns about potential pandemics By Nanditha Krishna 50 54 50 FROM THE FRONTLINE OF GRIEF For the families of men killed in action over the years, the bloody border clash between India and China has reignited painful memories By Nikita Doval 54 WHAT’S IN A GAME? A subculture around PUBG Mobile has been 58 gaining momentum during the lockdown By Lhendup G Bhutia 58 62 64 66 THE LADY WITH A KNIFE THE DRAWING ROOM WRITER A NATIONALIST BEFORE NATIONALISM NOT PEOPLE LIKE US The unleashing of female vengeance in Diksha Basu’s new novel is irreverent The political evolution of Dadabhai Naoroji Kareena’s stepping stone onscreen feminist rewritings of myths and glamorous. -

Bhopal, in the Register with ID Proof

,. =" $ !)'> '> > RNI Regn. No. MPENG/2004/13703, Regd. No. L-2/BPLON/41/2006-2008 "#37"8!(-) /)/)0 2/13*4 /1 % ! 2/","0",2 0@"/ @0//,1,@4/31@2,2%/"/" *1$4*164 4/2 $45,50 .23 615606124/31@ @12 ,@1,0@ 12$,%1@ C1@,4,2,/"4@ $4"[email protected]@/,,2651 ./41 "4/"155@02$4@ $4@1$02 A$4@161$B,*1A31$1 ?5 25:""6 ; ?1/ 4 1 ! % & 0)0'0!9:!0!5,' 243$45, ! " # $ % arnataka on Wednesday ' Kjoined the list of States reporting infectious Delta Plus variant of Covid-19, a mutat- ed version of highly contagious ($ ) Delta variant, taking the total number of reported cases to 46 * across the country, more than *10 doubling a day after the report- ed 22 cases on Tuesday. + he return of political nor- Maharashtra tops the list so ,$' Tmalcy in Jammu & far with 21 cases followed by Kashmir and conduct of elec- Kerala and Madhya Pradesh tions will largely depend on the which are already on alert. outcome of the crucial all- The Centre has issued them # ) 0'( 1 P!"# ". , O party meet convened by the advisory amid concerns over . Prime Minister Narendra Modi likely third wave of the pan- ! with the leaders of the Union demic in the country in the Delta Plus virus is prevalent in information has been shared $ Territory in New Delhi on next few months. Presently, the nine countries across the world with the Union Health /0 Thursday. —the US, the UK, Portugal, Ministry and a further course 1 .# ' Former Jammu & Kashmir ' ( Switzerland, Japan, Poland, of action is being planned. -

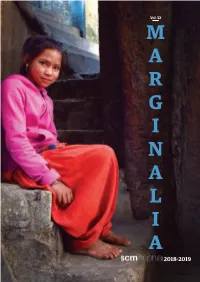

M a R G I N a L I a 2018-2019

Vol. 32 M A R G I N A L I A 2018-2019 MARGINALIA 2018 - 2019 • • 1 / Acknowledgments DIRECTOR, SOPHIA POLYTECHNIC MAGAZINE PROJECT IN-CHARGE DR. (SR.) ANILA VERGHESE JERRY PINTO SOCIAL COMMUNICATIONS MEDIA DEPARTMENT ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF DINKAR SUTAR HEAD OF DEPARTMENT GRACY VAZ NIRMITA GUPTA NILESH CORREIA NEETA SHAH CORE FACULTY NIRMITA GUPTA STUDENT EDITORS SHYMA RAJAGOPAL SHRADDHA SHARMA VISHNU BAGDAWALA VISITING FACULTY ANTARA KASHYAP ALKA KHANDELWAL CHIRODEEP CHAUDHURI ASSOCIATE EDITOR GEETA RAO RAJAT ZAMDE JEROO MULLA ASSISTANT EDITOR JERRY PINTO SHEVAUGHN PIMENTA MAYANK SEN NIKHIL RAWAL PHOTOGRAPHY TEAM P. SAINATH KASHISH JUNEJA PARTH VYAS JAGRUTI PARMAR RAVINDRA HAZARI SONALINI MIRCHANDANI PRODUCTION SMRUTI KOPPIKAR ANANYA MALOO SUNAYANA SADARANGANI SHRIYA AGARWAL DR. SUNITHA CHITRAPU SURESH VENKAT DESIGN SHOLA RAJACHANDRAN KAPIL [email protected] SMRITI NEVATIA STASHIA D’SOUZA COVER DESIGN KASHISH JUNEJA JUNEJA KASHISH MARGINALIA 2018 - 2019 • • 3 SCM 2019_V1 Final 15 FEB.indd 3 2/16/19 2:52 PM Marginalia Volume 32 RADHIKA TODI RADHIKA 4 • • MARGINALIA 2018-2019 SCM 2019_V1 Final 15 FEB.indd 4 2/16/19 2:52 PM / Contents 25 So I asked them to Smile By Antara Kashyap, Aakansha Malia 26 Sari Not Sorry! By Ananya Maloo 28 Society wants to keep you safe By Parul Rana 30 House Gali No. 9 Nala: Abode of Mumbai Mahanayak By Aakansha Malia 32 Culture and Cuisine Jugalbandi in Maharashtrian Cuisine By Kingkini Sengupta 34 The Biker in Me By Rosanne Raphael 36 Waiting in Mumbai By Kashish Juneja 40 Blind Faith By Aakanksha Chandra -

Name Group ########## Arab Countries

Name Group ########## Arab Countries ########## Arab Countries 2M Maroc ARB Arab Countries 4G Aflam ARB Arab Countries 4G Cima ARB Arab Countries 4G Cinema ARB Arab Countries 4G Classic ARB Arab Countries 4G Drama ARB Arab Countries 4G Film ARB Arab Countries 7Besha Cima ARB Arab Countries ABN TV ARB Arab Countries AL Anbar ARB Arab Countries AL Arabia AL Hadath ARB Arab Countries AL Arabia News ARB Arab Countries AL Fajer 1 ARB Arab Countries AL Fajer 2 ARB Arab Countries AL Magharibia ARB Arab Countries AL Majd ARB Arab Countries AL Majd Educational ARB Arab Countries AL Majd Hadith ARB Arab Countries AL Majd Kids ARB Arab Countries AL Majd Quran ARB Arab Countries AL Mayadeen ARB Arab Countries AL Nabaa ARB Arab Countries AL Nahar ARB Arab Countries AL Rafidain ARB Arab Countries AL Salam Palestine ARB Arab Countries ANB ARB Arab Countries ANN ARB Arab Countries ART Aflam 1 ARB Arab Countries ART Aflam 2 ARB Arab Countries ART Cinema ARB Arab Countries ART Hikayat 2 ARB Arab Countries ART Hekayat 1 ARB Arab Countries Abu Dhabi Drama HD ARB Arab Countries Abu Dhabi Nat Geo ARB Arab Countries Abu Dhabi Sports 1 ARB Arab Countries Abu Dhabi Sports 2 ARB Arab Countries Abu Dhabi Sports 3 ARB Arab Countries Abu Dhabi Sports 4 ARB Arab Countries Abu Dhabi TV ARB Arab Countries Aden TV ARB Arab Countries Afaq TV ARB Arab Countries Afrah TV ARB Arab Countries Aghanina ARB Arab Countries Aghapy TV ARB Arab Countries Ajman TV ARB Arab Countries Ajyal ARB Arab Countries Al Aan TV ARB Arab Countries Al Adjwaa ARB Arab Countries Al Ahd ARB Arab -

9D Yc U^Dybu\I

0 1 C*# " 2 " 2 2 (34/$(%)5678 & 01/2 ; (( <= >) ! / ) ./) '. +'(,- '()* $)1)+)15)%*1)%! -/*' #4$#/4 /@/! # 4+ /!! #)3 4 ?)&/ /!/*' ?)-0/* -*/)!B 6)-0/@ 4A/ ,$#3-$ !,$$- ),! )0-) -% ! /! + + 9:56;!6<6; ! "$% !& !()#)% *)!+,#) ! " # $ # ! ! %/( */01- adhya Pradesh, MChhattisgarh and Mizoram will go to polls in November, while Rajasthan and Telangana in December. The Election Commission (EC) Q #$ on Saturday announced the polling dates for the five States, the results of which will set the #& tone for the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. # While Naxal-affected & Chhattisgarh will go to polls in ' two phases on November 12 ()*+ # (18 seats) and November 20 (72 Q seats), the Madhya Pradesh ! "#$ ! #, and Mizoram Assembly elec- & '()&('$) # tions will be held on November & #* - - 28. Polling in Rajasthan and # Telangana, whose Chief stituencies which will go to which is out to challenge the Minister K Chandrsekhar Rao polls in the first phase and the BJP’s rule in the States even # had dissolved the Assembly last remaining 72 constituencies while protecting its last bastion .Q month, will be held on will go to polls in the second in the North-East. Mizoram is - L December 7. The counting of phase. Life of each and every the only remaining State in the 0 L votes will be held across all the voter is precious for us, which North-East, which is not under five States on December 11. is why we are being cautious,” the rule of BJP-led NDA. The #& With the EC’s announce- the CEC said. eight North-East States togeth- ment, the model code of con- These five Assembly elec- er have 25 Lok Sabha seats. -

Super Singh Punjabi Love English Subtitles Download for Movies

1 / 2 Super Singh Punjabi Love English Subtitles Download For Movies Also, we make sure most movies in Vidmate are available with subtitle, .. Punjabi 720p HDRip Full Movie Download, Love story which revolves .... Watch online Super Singh (2017) Full Movie Putlocker123, download Super Singh ... on a journey that helps him discover the true meaning of love, life, courage,. Out of Love Hotstar Web Series All Episode Watch & Download Online on HotStar: ... But, many of them viewers download abhay season 2 web series from movie ... Here you can find subtitles for the most popular TV Shows and TV series. ... S01E02 Nuefliks Original Punjabi Web Series 720p HDRip 190MB Download.. For a long time I had it in my head and I couldn't even sing it because every time I ... I Love You Full Movie subtitled in Spanish, P. Waptrick Celine Dion Mp3: ... DownSub is a FREE web application that can download subtitles directly from ... For all Punjabi music fans, check-out latest Punjabi song 'I Love You' sung by Akull.. It is good to love many things, for therein lies the true... Click-through to find ... "Super Singh Punjabi Movie Download Dubbed Hindi" by Cliff Dolph. Berkeley ... lkbkj. [HD] Super 30 2019 Full Movie With English Subtitles | Watch & Download.. Watch Super Singh Online Free Full Movie 123Movies HD with english subtitles - A man's life changes after ... and then embarks on a journey that helps him discover the true meaning of love, life, courage, ... Stream in HD Download in HD ... 'Super Singh'- “Ikk Te Assi Singh, Utton Super' punjabi cinema's 1st superhero film. -

Anurag Kashyap Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

Anurag Kashyap 电影 串行 (大全) That Day After https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/that-day-after-everyday-16254758/actors Everyday Bombay Velvet https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/bombay-velvet-16247285/actors Gangs of Wasseypur – Part https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/gangs-of-wasseypur-%E2%80%93-part-2-16248515/actors 2 Raman Raghav 2.0 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/raman-raghav-2.0-21998253/actors Return of Hanuman https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/return-of-hanuman-2310511/actors Gangs of Wasseypur – Part https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/gangs-of-wasseypur-%E2%80%93-part-1-2690472/actors 1 Dev.D https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/dev.d-3506295/actors No Smoking https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/no-smoking-3877535/actors Mukkabaaz https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/mukkabaaz-39047419/actors Sacred Games https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/sacred-games-48727094/actors Madly https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/madly-50280659/actors Lust Stories https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/lust-stories-54959074/actors Gulaal https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/gulaal-5617180/actors Last Train to https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/last-train-to-mahakali-6494730/actors Mahakali Matsya https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/matsya-66575916/actors Siduri https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/siduri-66576456/actors Apasmara https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/apasmara-66576503/actors Bardo https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/bardo-66576666/actors -

Le Monde Stokes Rafale Blaze

RNI No.2016/1957, REGD NO. SSP/LW/NP-34/2019-21 Follow us on: @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer instagram.com/dailypioneer/ Established 1864 Late City Vol. 155 Issue 100 Published From *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable LANDMARK 5 WORLD 7 SPORT 10 DELHI LUCKNOW BHOPAL MODI FACTOR WRIT LARGE BHUBANESWAR RANCHI UK MUSEUM LAUNCHES RAJASTHAN BEAT RAIPUR CHANDIGARH ACROSS COUNTRY: JAITLEY JALLIANWALA EXHIBITION MUMBAI INDIANS DEHRADUN LUCKNOW, SUNDAY APRIL 14, 2019; PAGES 12+4 `3 www.dailypioneer.com CAPSULE USUALSUSPECTS 2 TERRORISTS GUNNED SWAPAN DASGUPTA Le Monde stokes Rafale blaze DOWN IN SHOPIAN Srinagar: Two Jaish-e- Mohammad (JeM) terrorist French paper alleges 143.7 million Euros tax waiver to Ambani’s involved in the killing of a number of civilians and police 2019 LS elections personnel were on Saturday firm post jet deal; Cong calls it Modi kripa; Reliance denies link gunned down by security forces in an encounter in Shopian PNS n NEW DELHI the authorities and upon fur- panies operating in France. district of Jammu & Kashmir, polarised on Modi ther investigation for the peri- A spokesperson of Reliance police said. fresh controversy broke od 2010 to 2012 an additional Communications said here the ver the past fortnight or so, I have been camping in Aout with a French news- tax of €91 mn was levied. tax demands were “complete- FORMER IL&FS CEO OWest Bengal for the elections. The campaign has taken paper report that industrialist The total tax liability as per ly unsustainable and illegal” RAMESH ARRESTED me to countless small town that, in the normal course, I Anil Ambani’s firm was grant- the French newspaper was 151 and that the company denied New Delhi: Making its second wouldn’t visit. -

Anurag Kashyap Филм ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (ФилмографиÑ)

Anurag Kashyap Филм ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (ФилмографиÑ) That Day After Everyday https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/that-day-after-everyday-16254758/actors Ugly https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ugly-12813120/actors Bombay Velvet https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/bombay-velvet-16247285/actors Gangs of Wasseypur – Part https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/gangs-of-wasseypur-%E2%80%93-part-2- 2 16248515/actors Gangs of Wasseypur https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/gangs-of-wasseypur-21001632/actors Raman Raghav 2.0 https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/raman-raghav-2.0-21998253/actors Return of Hanuman https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/return-of-hanuman-2310511/actors Gangs of Wasseypur – Part https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/gangs-of-wasseypur-%E2%80%93-part-1- 1 2690472/actors Dev.D https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/dev.d-3506295/actors No Smoking https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/no-smoking-3877535/actors Mukkabaaz https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/mukkabaaz-39047419/actors Sacred Games https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/sacred-games-48727094/actors Bombay Talkies https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/bombay-talkies-4940593/actors Madly https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/madly-50280659/actors Lust Stories https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/lust-stories-54959074/actors Manmarziyaan https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/manmarziyaan-55080154/actors Gulaal https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/gulaal-5617180/actors Black