Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glasgow Cinema Programmes 1908-1914

Dougan, Andy (2018) The development of the audience for early film in Glasgow before 1914. PhD thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/9088/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] The development of the audience for early film in Glasgow before 1914 Andy Dougan Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Culture and Creative Arts College of Arts University of Glasgow May 2018 ©Andy Dougan, May 2018 2 In memory of my father, Andrew Dougan. He encouraged my lifelong love of cinema and many of the happiest hours of my childhood were spent with him at many of the venues written about in this thesis. 3 Abstract This thesis investigates the development of the audience for early cinema in Glasgow. It takes a social-historical approach considering the established scholarship from Allen, Low, Hansen, Kuhn et al, on the development of early cinema audiences, and overlays this with original archival research to provide examples which are specific to Glasgow. -

Frank Norris's "Mcteague" and Popular Culture

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1996 Frank Norris's "McTeague" and popular culture Ruby M Fowler University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Fowler, Ruby M, "Frank Norris's "McTeague" and popular culture" (1996). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 3158. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/ye6a-teps This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter 6ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Lillian Gish

Lillian Gish Lived: October 14, 1893 - February 27, 1993 Worked as: director, film actress, screenwriter Worked In: United States by Mark Garrett Cooper In 1920, Lillian Gish both delivered a landmark performance in D.W. Griffith’s Way Down East and directed her sister Dorothy in Remodelling Her Husband. This was her sole director credit in a career as a screen actor that began with An Unseen Enemy in 1912 and ended with The Whales of August in 1987. Personal correspondence examined by biographer Charles Affron shows that Gish lobbied Griffith for the opportunity to direct and approached the task with enthusiasm. In 1920, in Motion Picture Magazine, however, Gish offered the following assessment of her experience: “There are people born to rule and there are people born to be subservient. I am of the latter order. I just love to be subservient, to be told what to do” (102). One might imagine that she discovered a merely personal kink. In a Photoplay interview that same year, however, she extended her opinion to encompass all women and in doing so slighted Lois Weber, one of Hollywood’s most productive directors. “I am not strong enough” to direct, Gish told Photoplay, “I doubt if any woman is. I understand now why Lois Weber was always ill after a picture” (29). What should historical criticism do with such evidence? By far the most common approach has been to argue that Gish did not really mean what the press quotes her as saying. Alley Acker, for instance, urges us not to be fooled by Gish’s “Victorian modesty” and goes on to provide evidence of her authority on the set (62). -

1968-269.Pdf

1968 DECEMBER SPECIALS (C) SUNDAY, DEC. I--8:00-9:00 PM... "ANN MARGARET SHOW" (C) TUESDAY, DEC. 3--6:30-7:30 PM... NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SPECIAL "REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS" (C) SUNDAY, DEC. 8m6:30-7:00 PM... "A CHARLIE BROWN CHRISTMAS" JON JOHNSON JAKE HESS (C) SUNDAY, DEC. 22--6:00-6:30 PM... "HOW THE GRINCH STOLE CHRISTMAS" CHANNEL 5 OLD TIME (C) SATURDAY, DEC. 28--12:00 N TO CONCLUSION MORNING WEATHER SINGING CONVENTION ¯.. BLUE/GREY FOOTBALL GAME 7:55 AM (MON.mFRI. 12:05-12:30 PM (¢) SATURDAY, DEC. 28--2:45 PM TO CONCLUSION... SUN BOWL GAME CHANNEL 5 NEWS (MON.--FRL) 12 NOON (MON.mFRI.) EVENING SUN. MaN. TUES. WED. THURS. FRI. SAT. Weekend Report CBS CBS CBS CBS CBS Roger News Evening Evening Evening Evening Evening Weather News (c) News Ic) News () News (c) News (c) Mudd Sports W, Cronklte W. Crank;re W. Cronkite W. Cronklte W. Cronkite News Weekend 6 Channel 5 Channel 5 Channel 5 Channel 5 Channel 5 Report Lassie News News News News News (c) Weather Weather Weather Weather Weather Sports Sports Sports Sports Sports 6:30 Gentle Ben Blondie (c) The Wild, Jackie Gunsmoke Lancer Daktori Wild (c) (c) (c) Gleason West Show () Ed Hawaii Sullivan Five-o 7:30 Show (c) (c) Here’s Two Good Gomer My 3 Lucy Guys Pyle Sons (c) (c) Red Ske)eton Hour Mayberry Beverly Hogan’s The (c) Hillbillies Heroes Smothers R.FD. (c) Brothers (c) (c) 8:30 Comedy Hour Doris Family Green pefHcoat Affair Day Show Acres Thursday Junction (c] (c) Night Friday Movie Night 9 (Most in Movie Marshal color) (c) Dillon Jonathan M~ssion Carol CBS Winters 9:30 Impossible eurnette -

Lillian Diana Gish

Adrian Paul Botta ([email protected]) Lillian Diana Gish Lillian Diana Gish[1] (October 14, 1893 – February 27, 1993) was an American actress of the screen and stage,[2] as well as a director and writer whose film acting career spanned 75 years, from 1912 in silent film shorts to 1987. Gish was called the First Lady of American Cinema, and she is credited with pio - neering fundamental film performing techniques. Gish was a prominent film star of the 1910s and 1920s, partic - ularly associated with the films of director D. W. Griffith, includ - ing her leading role in the highest-grossing film of the silent era, Griffith's seminal The Birth of a Nation (1915). At the dawn of the sound era, she returned to the stage and appeared in film infrequently, including well-known roles in the controversial western Duel in the Sun (1946) and the offbeat thriller The Night of the Hunter (1955). She also did considerable television work from the early 1950s into the 1980s and closed her career playing, for the first time, oppo - site Bette Davis in the 1987 film The Whales of August (which would prove to be one of Davis's last on-screen appearances). In her later years Adrian Paul Botta ([email protected]) In her later years Gish became a dedicated advocate for the appreciation and preservation of silent film. Gish is widely consid - ered to be the great - est actress of the silent era, and one of the greatest ac - tresses in cinema history. Despite being better known for her film work, Gish was also an accom - plished stage ac - tress, and she was inducted into the American Theatre Hall of Fame in 1972. -

UFVA Final Conference Program

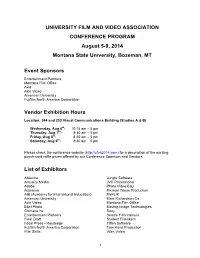

UNIVERSITY FILM AND VIDEO ASSOCIATION CONFERENCE PROGRAM August 5-9, 2014 Montana State University, Bozeman, MT Event Sponsors Entertainment Partners Montana Film Office Avid Axle Video American University Fujifilm North America Corporation Vendor Exhibition Hours Location: 244 and 233 Visual Communications Building (Studios A & B) Wednesday, Aug 6th: 10:15 am – 5 pm Thursday, Aug 7th: 8:30 am – 5 pm Friday, Aug 8th: 8:30 am – 5 pm Saturday, Aug 9th: 8:30 am – 5 pm Please check the conference website (http://ufva2014.com) for a description of the exciting punch-card raffle prizes offered by our Conference Sponsors and Vendors. List of Exhibitors Ablecine Jungle Software Actuality Media JVC Professional Adobe Photo Video Edu Adorama Michael Wiese Production AIB (Academy for International Education) MyFLIK American University Mole Richardson Co. Axle Video Montana Film Office B&H Photo Moving Image Technologies Chimera Inc. Sony Entertainment Partners Seattle Film Institute Final Draft Student Filmakers Focal Press - Routledge Tiffen Software Fujifilm North America Corporation Tom Kane Production Film Skills Vitec Video 1 Need Help? Need Help? Staff tech assistants can be identified by their blue staff shirts and will be assigned to each presentation venue. Two phone lines have been established, too. For help call either (406) 223-9129 or (406) 223-4921. Phones will be active beginning at 12:00 PM on August 5th, 2014. 2 Tuesday, August 5th Tuesday, August 5th UFVF Board Meeting – 8:00 am to 12:00 pm (Alumni Foundation Building – Great Room) -

DON JUAN CANTO FIFTH Edited by Peter Cochran

DON JUAN CANTO FIFTH edited by Peter Cochran (fair copy ): Begun Ravenna Oct r 16 th 1820 1. When amatory poets sing their Loves In liquid lines mellifluously bland, And pair their rhymes as Venus yokes her doves, They little think what mischief is in hand; The greater their success the worse it proves, 5 As Ovid’s verse 1 may give to understand; Even Petrarch’s 2 Self, if judged with due Severity, Is the Platonic 3 pimp of all posterity. 2. I therefore do renounce all amorous writing, Except in such a way as not to attract; 10 Plain – simple – short, and by no means inviting, But with a moral to each error tacked, Formed rather for instructing than delighting, And with all passions in their turn attacked; Now, if my Pegasus 4 should not be shod ill, 15 This poem will become a moral model. 1: Ovid’s verse: see above, canto I, 329: Ovid’s a rake, as half his verses show him. B.’s reference here is to Amores, I ii 23: necte comam myrto, maternas iunge columbas (Bind thy locks with the myrtle, yoke thy mother’s doves). Ovid is addressing Cupid (Venus’ son) and consenting to be led in triumph by him, with Modesty and Conscience both fettered. 2: Petrarch: Italian Renaissance poet of Platonic love: see above, III, ll.63-4. 3: Platonic: Byronic shorthand for “pseudo-spiritual”: see above, I, ll.629, 885 and 921. 4: Pegasus: the mythical winged steed, emblematic of a poet’s inspiration: see above, IV, l.3. -

University Microfilms. a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor. Michigan

71-22,452 BURMAN, Howard Vincent, 1942- A HISTORY AND EVALUATION OF THE NEW DRAMATISTS COMMITTEE. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 Speech-Theater University Microfilms. A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor. Michigan © Copyright by Howard Vincent Burman 1971 A HISTORY AND EVALUATION OF THE NEW DRAMATISTS COMMITTEE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Howard Vincent Burman, B.A* ***** The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by Adviser Division of Theatre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation to the many persons whose assistance has contributed to the completion of this dissertation* Special thanks are due to Mrs. Letha Nims and the present and former members of the New Dramatists Committee particu larly Robert Anderson, Paddy Chayefsky, Mary K, Frank, the late Howard Lindsay, and Michaela 0*Harra» who generously made both their time and files available to the author; to Dr. David Ayers for proposing the topic; to my advisers Drs. Roy Bowen, Arthur Housman and John Morrow for their prompt and valuable advice and direction; to Mrs. Tara Bleier for valuable re-writing assistance; to Mrs. Irene Simpkins for expert final typing and editing; to Mrs. Susan Holmes for her critical reading; to Mrs. Mary Ethel Neal for "emergency" typing aid; to my brother-in-law Frank Krebs for his "messenger" service; and to the U.S. Post Office for not losing my manuscript during its many cross-country trips. Also, to my wife, Karen, who, in addition to devoting countless hours of editing, proofreading and typing, has been a inexhaustible source of advice and encouragement. -

The Effects of Light on Human Consciousness As Exemplified in Johann Wolfgang Von Goethes' Fairy Tale

THE EFFECTS OF LIGHT ON HUMAN CONSCIOUSNESS AS EXEMPLIFIED IN JOHANN WOLFGANG VON GOETHES' FAIRY TALE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DNISION OF THE UNNERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURE OF EUROPEANDTHEAMEIDCAS (GERMAN) DECEMBER 2002 By Sylvia Zietze Thesis Committee: Jiirgen G. Sang, Chairperson Niklaus R. Schweizer Dennis W. Carroll iii © Copyright by Sylvia Zietze IV In memoriam William F. Scherer. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to thank Professor Jiirgen G. Sang for all the time he invested in assisting me with this thesis and for his profound advice during a period ofendless revisions. I am also very grateful to the members ofmy thesis committee, Professor Niklaus R. Schweizer, and Professor Dennis W. Carroll, for their helpful and inspiring suggestions. Furthermore, I want to acknowledge Professor Markus Wessendorf, Professor Maryann Overstreet, and Christina Bolter for their encouragement and support. This thesis is dedicated to the late Professor William F. Scherer, my long-time academic advisor and close friend. VI Table of Contents Acknowledgements V Introduction 1 Chapter One: I. Historical background ofthe Fairy Tale 4 2. Sununary ofthe Fairy Tale 11 Chapter Two: I. Botanies in the Fairy Tale 16 Chapter Three: 1.Stray-light and Light 21 2.The Lamp .33 3.Gold and Glitter. .43 Chapter Four: 1. The Shadow and Dramatis Personae ..49 2. Transformation and Death 58 Conclusion 64 Appendices: 1. Biography ofJohann Wolfgang von Goethe 75 Bibliography 84 1 Introduction The topic ofthis thesis is the analysis ofthe effects oflight on human consciousness as exemplified in Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Fairy Tale. -

Biography of D.W. Griffith David Wark Griffith Was Born in La Grange

Biography of D.W. Griffith David Wark Griffith was born in La Grange, Kentucky on January 22, 1875. After stints as both writer and actor of poetry and plays, Griffith first entered the motion picture industry as an actor for Edison Studios in 1907. He moved over to Biograph in 1908 for the salary of $5 a day. Griffith's work at Biograph would forever change the way movies were made. Biograph was one of the first motion picture studios in America, when films were sold outright by the foot, and not rented as they are today. Films were silent and no more than one reel in length (a running time of about 12 minutes). At a price of 10-cents a foot, the cost of a reel of film was about $100. When Griffith first came to Biograph, the studio was only selling about 20 copies of each new film and was in poor financial condition. Biograph was in pressing need of a director. The job was offered to Griffith at an increase in salary, but he was reluctant to take it. He was working steadily and was afraid that if he failed he would lose his job as an actor. Henry Marvin, founder of Biograph, assured Griffith that if he did fail as a director, his acting chores would continue. Griffith reluctantly accepted. Griffith had only a rudimentary understanding of film making. He knew that film directors were no more than sheepherders, moving the actors from one place to another on the screen. The cameraman was king. Biograph had two: Arthur Marvin, brother of Griffith’s boss, and a German immigrant named G.W. -

Biograph Co., Production

GUIDE TO THE BIOGRAPH COLLECTION MUSEUM OF MODERN ART DEPARTMENT OF FILM THE CELESTE BARTOS INTERNATIONAL FILM STUDY CENTER Compiled by Ronald S. Magliozzi and Alice Black Department of Film and Video Museum of Modern Art New York 1 MUSEUM OF MODERN ART DEPARTMENT OF FILM THE BIOGRAPH COLLECTION Initial processing completed December 31, 1996, by Alice Black, under the supervision of Ronald S. Magliozzi. Final arrangement and description in process from October 1999, by Ronald S. Magliozzi. As part of the Film Study Center's Special Collections, the material in the Biograph Collection has been culled from a number of sources. Catalogued together these documents trace the production history of this early American studio from its inception as the American Mutoscope Company in December 1895, through its development from the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company to the Biograph Company in the Spring of 1909. The company was formed by four men: William Kennedy Laurie Dickson, Herman Casler, Harry Norton Marvin and Elias Bernard Koopman who created and marketed their unique projection system, the Biograph. By the early 1900's the prosperity of the Biograph company posed a significant threat to the market dominated by Thomas A. Edison. A successful court challenge against Edison's powerful patent lead to the establishment of the United Film Services Protective Association to protect their interests against the exhibitors in 1907. Home to director D.W.Griffith, Biograph became one of the most successful studios of the period. The material gathered in the Biograph Collection documents the studio's early business activities as well as production practices of the later period. -

With the Fire on High, I Don’T Know What to Cook

Dedication For the women in my family, who have gathered me when I needed gathering and given me a launchpad when I needed to dream. Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Part One: The Sour Day One Emma Sister Friends Magic The Authors That Girl Immersed Kitchen Sink Conversations Chefdom The New Guy On Loss Farewells Lovers & Friends Returns Mama New Things College Essay: First Draft An Art Form Malachi Black Like Me The Read Salty Tantrums and Terrible Twos Fickle Fatherhood Exhaustion A Tale of Two Cities Fail Catharsis Pudding with a Pop Living Large & Lavish Impossibilities Santi Three’s Company Phone Calls Julio, Oh, Julio School Going Places Basura Home Is Where I Been Grown Hurricane Season Part Two: The Savory Skipping Forgiveness Sisterhood Invitations Sous Chef Anniversary Netflix, No Chill Ramifications Café Sorrel Taste Buds New Beginnings Guess Who’s Back? Visitation Proposals The Bright Side Team Player Coven Dreams Every Day I’m Hustling Out of the Frying Pan Crunch Time To the Bone Winter Dinner A Numbers Game Hook, Line, and Sinker Complications Pride On Ice Side by Side Chivalry When It Rains It Pours Blood Boil Holidays New Year, New Recipes Money Talks Flash Spain Arrival Roommates The First Night Chef Amadí Cluck, Cluck Game Time Winning The Roots Check-In Gilded Histories The Chase Children Smooch Cozy Ugly Leslie Settled Boys Will Be Heart-to-Heart Ready? Last Day Duende Home Acceptance Surprises Just Fine Next Steps Love Part Three: The Bittersweet Stuck Accepted Prom The Rising Promotion Ceremony Moving Forward Acknowledgments About the Author Books by Elizabeth Acevedo Back Ad Copyright About the Publisher Part One The Sour EMONI’S “When Life Gives You Lemons, Make Lemon Verbena Tembleque” RECIPE Serves: Your heart when you are missing someone you love.