Cuora Flavomarginata (Gray 1863) – Yellow-Margined Box Turtle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turtles #1 Among All Species in Race to Extinction

Turtles #1 among all Species in Race to Extinction Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation and Colleagues Ramp Up Awareness Efforts After Top 25+ Turtles in Trouble Report Published Washington, DC (February 24, 2011)―Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation (PARC), an Top 25 Most Endangered Tortoises and inclusive partnership dedicated to the conservation of Freshwater Turtles at Extremely High Risk the herpetofauna--reptiles and amphibians--and their of Extinction habitats, is calling for more education about turtle Arranged in general and approximate conservation after the Turtle Conservation Coalition descending order of extinction risk announced this week their Top 25+ Turtles in Trouble 1. Pinta/Abingdon Island Giant Tortoise report. PARC initiated a year-long awareness 2. Red River/Yangtze Giant Softshell Turtle campaign to drive attention to the plight of turtles, now the fastest disappearing species group on the planet. 3. Yunnan Box Turtle 4. Northern River Terrapin 5. Burmese Roofed Turtle Trouble for Turtles 6. Zhou’s Box Turtle The Turtle Conservation Coalition has highlighted the 7. McCord’s Box Turtle Top 25 most endangered turtle and tortoise species 8. Yellow-headed Box Turtle every four years since 2003. This year the list included 9. Chinese Three-striped Box Turtle/Golden more species than previous years, expanding the list Coin Turtle from a Top 25 to Top 25+. According to the report, 10. Ploughshare Tortoise/Angonoka between 48 and 54% of all turtles and tortoises are 11. Burmese Star Tortoise considered threatened, an estimate confirmed by the 12. Roti Island/Timor Snake-necked Turtle Red List of the International Union for the 13. -

Suggested Guidelines for Reptiles and Amphibians Used in Outreach

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS USED IN OUTREACH PROGRAMS Compiled by Diane Barber, Fort Worth Zoo Originally posted September 2003; updated February 2008 INTRODUCTION This document has been created by the AZA Reptile and Amphibian Taxon Advisory Groups to be used as a resource to aid in the development of institutional outreach programs. Within this document are lists of species that are commonly used in reptile and amphibian outreach programs. With over 12,700 species of reptiles and amphibians in existence today, it is obvious that there are numerous combinations of species that could be safely used in outreach programs. It is not the intent of these Taxon Advisory Groups to produce an all-inclusive or restrictive list of species to be used in outreach. Rather, these lists are intended for use as a resource and are some of the more common species that have been safely used in outreach programs. A few species listed as potential outreach animals have been earmarked as controversial by TAG members for various reasons. In each case, we have made an effort to explain debatable issues, enabling staff members to make informed decisions as to whether or not each animal is appropriate for their situation and the messages they wish to convey. It is hoped that during the species selection process for outreach programs, educators, collection managers, and other zoo staff work together, using TAG Outreach Guidelines, TAG Regional Collection Plans, and Institutional Collection Plans as tools. It is well understood that space in zoos is limited and it is important that outreach animals are included in institutional collection plans and incorporated into conservation programs when feasible. -

Batagur Affinis I Northern River Terrapin I Southern River Terrapin

IDENTIFICATION OF COMMONLY TRADED WILDLIFE WITH A FOCUS ON THE GOLDEN TRIANGLE LAO PDR · MYANMAR · THAILAND IDENTIFICATION OF COMMONLY TRADED WILDLIFE WITH A FOCUS ON THE GOLDEN TRIANGLE LAO PDR · MYANMAR · THAILAND WWW.TRAFFIC.ORG TRAFFIC is a leading non-governmental organisation working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. Reproduction of material appearing in this guide requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. © TRAFFIC 2020. Copyright of material published in this guide is vested in TRAFFIC. Suggested Citation: Beastall, C.A. and Chng, S.C.L. (2020). Identification of Commonly Traded Wildlife with a focus on the Golden Triangle (Lao PDR, Myanmar and Thailand). TRAFFIC, Southeast Asia Regional Office, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. USING THIS GUIDE This guide has been designed to assist identification of wildlife species which are commonly found in trade in the Golden Triangle (Lao PDR, Myanmar and Thailand). It is an update of the Identification Sheets for Wildlife Species Traded in Southeast Asia produced for The Association of Southeast Asian Nations—Wildlife Enforcement Network (ASEAN-WEN) between 2008 and 2013. This version was produced in 2020. This guide provides information on key identification features for the species or taxa, and what it is traded as. -

Do Zoos Work at Raising Awareness? Quantifying the Impact of Informal Education on Adults Visiting Japanese Zoos

________________________________________________________ Do zoos work at raising awareness? Quantifying the impact of informal education on adults visiting Japanese zoos ___________________________________________________________________ AYAKO UOZUMI “A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Science and the Diploma of Imperial College London.” September 2010 1 DECLARATION OF OWN WORK I declare that this thesis (insert full title) …………………………………………………………………………………………… …………………………………………………………………………………………… …………………………………………………………………………………………… …………………………………………………………………………………………… is entirely my own work and that where material could be construed as the work of others, it is fully cited and referenced, and/or with appropriate acknowledgement given. Signature …………………………………………………….. Name of student …………………………………………….. (please print) Name of Supervisor …………………………………………. 2 1 INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................... 8 1.1 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES..........................................................................................................................................10 1.2 OVERVIEW OF THESIS STRUCTURE ....................................................................................................................10 2 BACKGROUND........................................................................................................................................11 2.1 A BRIEF HISTORY OF -

Species Identification of Shed Snake Skins in Taiwan and Adjacent Islands

Zoological Studies 56: 38 (2017) doi:10.6620/ZS.2017.56-38 Open Access Species Identification of Shed Snake Skins in Taiwan and Adjacent Islands Tein-Shun Tsai1,* and Jean-Jay Mao2 1Department of Biological Science and Technology, National Pingtung University of Science and Technology 1 Shuefu Road, Neipu, Pingtung 912, Taiwan 2Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, National Ilan University No.1, Sec. 1, Shennong Rd., Yilan City, Yilan County 260, Taiwan. E-mail: [email protected] (Received 28 August 2017; Accepted 25 November 2017; Published 19 December 2017; Communicated by Jian-Nan Liu) Tein-Shun Tsai and Jean-Jay Mao (2017) Shed snake skins have many applications for humans and other animals, and can provide much useful information to a field survey. When properly prepared and identified, a shed snake skin can be used as an important voucher; the morphological descriptions of the shed skins may be critical for taxonomic research, as well as studies of snake ecology and conservation. However, few convenient/ expeditious methods or techniques to identify shed snake skins in specific areas have been developed. In this study, we collected and examined a total of 1,260 shed skin samples - including 322 samples from neonates/ juveniles and 938 from subadults/adults - from 53 snake species in Taiwan and adjacent islands, and developed the first guide to identify them. To the naked eye or from scanned images, the sheds of almost all species could be identified if most of the shed was collected. The key features that aided in identification included the patterns on the sheds and scale morphology. -

Herp. Bulletin 101.Qxd

Mountain wolf snake ( Lycodon r . ruhstrati ) predation on an exotic lizard, Anolis sagrei , in Chiayi County, Taiwan GERRUT NORVAL 1, SHAO-CHANG HUANG 2 and JEAN-JAY MAO 3 1 Applied Behavioural Ecology & Ecosystem Research Unit, Department of Nature Conservation, UNISA, Private Bag X6, Florida, 1710, Republic of South Africa . Email: [email protected] [author for correspondence] 2 Department of Life Science, Tunghai University. No. 181, Sec. 3, Taichung-Kan Road, Taichung, 407- 04, Taiwan, R.O.C . 3 Department of Natural Resources, National I-Lan University, No. 1, Shen-Lung Rd., Sec. 1, I-Lan City 260, Taiwan, R.O.C . ABSTRACT – The Mountain wolf snake ( Lycodon ruhstrati ruhstrati ) is a common snake species at low elevations all over Taiwan. Still, it appears to be poorly studied in Taiwan and adjacent areas since little has been reported about this species. On 26 th August 2002 ten L. r. ruhstrati eggs were obtained from an adult female, one of two that were caught a day before, and eight of the eggs hatched successfully on 14 th October 2002. While in captivity all the adults preyed upon Anolis sagrei , which were given to them as prey, while two neonates accepted A. sagrei hatchlings offered to them as food. On February 18 th , 2006, a DOR Mountain wolf snake, with an A. sagrei in its stomach, was found on a tarred road in Santzepu, Sheishan District, Chiayi County. This appears to be the first report from Taiwan of the Mountain wolf snake ( L. r. ruhstrati ) preying on the exotic introduced lizard A. -

Gliding Ability of the Siberian Flying Squirrel Pteromys Volans Orii

Mammal Study 32: 151–154 (2007) © the Mammalogical Society of Japan Gliding ability of the Siberian flying squirrel Pteromys volans orii Yushin Asari1,2, Hisashi Yanagawa2,* and Tatsuo Oshida2 1 The United Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Iwate University, Morioka 020-8550, Japan 2 Laboratory of Wildlife Ecology, Obihiro University of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, Obihiro 080-8555, Japan Abstract. Forest fragmentation is a threat to flying squirrel population due to dependence on gliding locomotion in forests. Therefore, it is essential to understand their gliding ability. The gliding locomotion of Pteromys volans orii, were observed from July 2003 to June 2005, in Obihiro, Hokkaido, Japan. The horizontal distance and glide ratio obtained from 31 glides were employed as indicators to know their gliding ability. The gliding ability was not affected by weight and sex in the Siberian flying squirrel. Mean horizontal distance and glide ratio were 18.90 m and 1.70 with great variation. Although maximum values were 49.40 m (horizontal distance) and 3.31 (glide ratio), most of the horizontal distance and glide ratio were in the ‘10–20 m’ and ‘1.0–1.5’, respectively. Therefore, to retain the flying squirrel populations, forest gaps should not exceed the distance traversable with a glide ratio of 1.0 (distance between forests/tree height at the forest edg). Key words: gliding ability, gliding ratio, horizontal distance, Pteromys volans orii. The Siberian flying squirrel, Pteromys volans, ranges The key purposes of gliding may be to avoid predators over northern parts of the Eurasia, and from Korea to or to minimize the energy costs of moving (Goldingay Hokkaido, Japan. -

Care of the Chinese Box Turtle Husbandry & Diet Information

Care of the Chinese Box Turtle Husbandry & Diet Information Quick Facts about Cuora flavomarginata • Lifespan: 20 years • Average weight: 400-750 grams • Shell length: 14-16.5 cm (5.5-6.5 in) Natural History This charming box turtle is native to the rice patty and pond environments of Taiwan and southern China. Reproduction The nesting season ranges from March to August, with up to 3 or 4 clutches laid annually. Clutches averaging 1-3 eggs. Incubation temperatures should be maintained at 28ºC (83ºF), humidity at 90%-100%, with ample aeration. Eggs hatch within 75-90 days. Enclosure The Chinese box turtle is a semi-aquatic species, and an outdoor enclosure with an accessible pond is best. For indoor housing, this species can be set up in a 30-55 gallon (114-208 L) aquarium with wood branches and a rock for basking. The tank should have an aquatic set up which consists of half land with a basking area and half water. 50% Land 50% Water • Maintain humidity between 60%-70% • Provide a shallow panel of water in the during the daytime. tank measuring 7-20 cm (3-8 in) in depth • Provide a basking site at 29-32ºC (85-90ºF) • As this species originates from the tropics, and full-spectrum (UVB) lighting maintain water temperature between 24- • Avoid any substrate that is small enough to 26ºC (75-80ºF) with the use of a be ingested such as bark, sand, millet, or submersible tank heater walnut shells • At night, the temperature SHOULD NOT drop below 24ºC (75ºF). Diet Asian box turtles are omnivorous, with a preference for vegetables. -

Summary Report of Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 5

Summary Report of Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 5 Summary Report of Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 5 Prepared by: Amy J. Benson, Colette C. Jacono, Pam L. Fuller, Elizabeth R. McKercher, U.S. Geological Survey 7920 NW 71st Street Gainesville, Florida 32653 and Myriah M. Richerson Johnson Controls World Services, Inc. 7315 North Atlantic Avenue Cape Canaveral, FL 32920 Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 4401 North Fairfax Drive Arlington, VA 22203 29 February 2004 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………... ...1 Aquatic Macrophytes ………………………………………………………………….. ... 2 Submersed Plants ………...………………………………………………........... 7 Emergent Plants ………………………………………………………….......... 13 Floating Plants ………………………………………………………………..... 24 Fishes ...…………….…………………………………………………………………..... 29 Invertebrates…………………………………………………………………………...... 56 Mollusks …………………………………………………………………………. 57 Bivalves …………….………………………………………………........ 57 Gastropods ……………………………………………………………... 63 Nudibranchs ………………………………………………………......... 68 Crustaceans …………………………………………………………………..... 69 Amphipods …………………………………………………………….... 69 Cladocerans …………………………………………………………..... 70 Copepods ……………………………………………………………….. 71 Crabs …………………………………………………………………...... 72 Crayfish ………………………………………………………………….. 73 Isopods ………………………………………………………………...... 75 Shrimp ………………………………………………………………….... 75 Amphibians and Reptiles …………………………………………………………….. 76 Amphibians ……………………………………………………………….......... 81 Toads and Frogs -

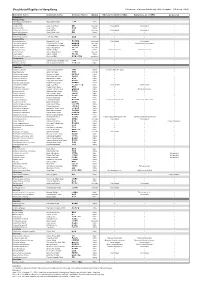

Checklist of Reptiles in Hong Kong © Programme of Ecology & Biodiversity, HKU (Last Update: 10 September 2012)

Checklist of Reptiles in Hong Kong © Programme of Ecology & Biodiversity, HKU (Last Update: 10 September 2012) Scientific name Common name Chinese Name Status Ades & Kendrick (2004) Karsen et al. (1998) Uetz et al. Testudines Platysternidae Platysternon megacephalum Big-headed Terrapin 大頭龜 Native Cheloniidae Caretta caretta Loggerhead Turtle 蠵龜 Uncertain Not included Not included Chelonia mydas Green Turtle 緣海龜 Native Eretmochelys imbricata Hawksbill Turtle 玳瑁 Uncertain Not included Not included Lepidochelys olivacea Pacific Ridley Turtle 麗龜 Native Dermochelyidae Dermochelys coriacea Leatherback Turtle 稜皮龜 Native Geoemydidae Cuora amboinensis Malayan Box Turtle 馬來閉殼龜 Introduced Not included Not included Cuora flavomarginata Yellow-lined Box Terrapin 黃緣閉殼龜 Uncertain Cistoclemmys flavomarginata Cuora trifasciata Three-banded Box Terrapin 三線閉殼龜 Native Mauremys mutica Chinese Pond Turtle 黃喉水龜 Uncertain Mauremys reevesii Reeves' Terrapin 烏龜 Native Chinemys reevesii Chinemys reevesii Ocadia sinensis Chinese Striped Turtle 中華花龜 Uncertain Sacalia bealei Beale's Terrapin 眼斑水龜 Native Trachemys scripta elegans Red-eared Slider 巴西龜 / 紅耳龜 Introduced Trionychidae Palea steindachneri Wattle-necked Soft-shelled Turtle 山瑞鱉 Uncertain Pelodiscus sinensis Chinese Soft-shelled Turtle 中華鱉 / 水魚 Native Squamata - Serpentes Colubridae Achalinus rufescens Rufous Burrowing Snake 棕脊蛇 Native Achalinus refescens (typo) Ahaetulla prasina Jade Vine Snake 綠瘦蛇 Uncertain Amphiesma atemporale Mountain Keelback 無顳鱗游蛇 Native -

P. 1 AC27 Inf. 7 (English Only / Únicamente En Inglés / Seulement

AC27 Inf. 7 (English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________ Twenty-seventh meeting of the Animals Committee Veracruz (Mexico), 28 April – 3 May 2014 Species trade and conservation IUCN RED LIST ASSESSMENTS OF ASIAN SNAKE SPECIES [DECISION 16.104] 1. The attached information document has been submitted by IUCN (International Union for Conservation of * Nature) . It related to agenda item 19. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat or the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. AC27 Inf. 7 – p. 1 Global Species Programme Tel. +44 (0) 1223 277 966 219c Huntingdon Road Fax +44 (0) 1223 277 845 Cambridge CB3 ODL www.iucn.org United Kingdom IUCN Red List assessments of Asian snake species [Decision 16.104] 1. Introduction 2 2. Summary of published IUCN Red List assessments 3 a. Threats 3 b. Use and Trade 5 c. Overlap between international trade and intentional use being a threat 7 3. Further details on species for which international trade is a potential concern 8 a. Species accounts of threatened and Near Threatened species 8 i. Euprepiophis perlacea – Sichuan Rat Snake 9 ii. Orthriophis moellendorfi – Moellendorff's Trinket Snake 9 iii. Bungarus slowinskii – Red River Krait 10 iv. Laticauda semifasciata – Chinese Sea Snake 10 v. -

Variation and Systematics of the Malayan Snail-Eating Turtle, Malayemys Subtrijuga (Schlegel and Müller, 1844)

VARIATION AND SYSTEMATICS OF THE MALAYAN SNAIL-EATING TURTLE, MALAYEMYS SUBTRIJUGA (SCHLEGEL AND MÜLLER, 1844) by Timothy R. Brophy A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Environmental Science and Public Policy Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Department Chairperson ___________________________________________ Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Fall Semester 2002 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Variation and Systematics of the Malayan Snail-eating Turtle, Malayemys subtrijuga (Schlegel and Müller, 1844) A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University By Timothy R. Brophy Master of Science Marshall University, 1995 Director: Carl H. Ernst, Professor Department of Biology Fall Semester 2002 George Mason University Fairfax, VA ii Copyright 2002 Timothy R. Brophy All Rights Reserved iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my children, Timmy and Emily, who have made this entire project worthwhile. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study would not have been possible without specimen loans or access from the following museum curators, technicians, and collection managers: C.W. Meyers and C.J. Cole, American Museum of Natural History, New York; C. McCarthy, British Museum (Natural History), London; J.V. Vindum, E.R. Hekkala, and M. Koo, California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco; E.J. Censky, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh; P.C.H. Pritchard and G. Guyot, Chelonian Research Institute, Oviedo, FL; K. Thirakhupt and P.P. van Dijk, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand; A. Resetar, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago; D.L.