Malaysia's Development Challenges for Moving up the Value Chain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malaysia Industrial Park Directory.Pdf

MALAYSIA INDUSTRIAL PARK DIRECTORY CONTENT 01 FOREWORD 01 › Minister of International Trade & Industry (MITI) › Chief Executive Officer of Malaysian Investment Development Authority (MIDA) › President, Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers (FMM) › Chairman, FMM Infrastructure & Industrial Park Management Committee 02 ABOUT MIDA 05 03 ABOUT FMM 11 04 ADVERTISEMENT 15 05 MAP OF MALAYSIA 39 06 LISTING OF INDUSTRIAL PARKS › NORTHERN REGION Kedah & Perlis 41 Penang 45 Perak 51 › CENTRAL REGION Selangor 56 Negeri Sembilan 63 › SOUTHERN REGION Melaka 69 Johor 73 › EAST COAST REGION Kelantan 82 Terengganu 86 Pahang 92 › EAST MALAYSIA Sarawak 97 Sabah 101 PUBLISHED BY PRINTED BY Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers (7907-X) Legasi Press Sdn Bhd Wisma FMM, No 3, Persiaran Dagang, No 17A, (First Floor), Jalan Helang Sawah, PJU 9 Bandar Sri Damansara, 52200 Kuala Lumpur Taman Kepong Baru, Kepong, 52100 Kuala Lumpur T 03-62867200 F 03-62741266/7288 No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form E [email protected] without prior permission from Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers. All rights reserved. All information and data www.fmm.org.my provided in this book are accurate as at time of printing MALAYSIA INDUSTRIAL PARK DIRECTORY FOREWORD MINISTER OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE & INDUSTRY (MITI) One of the key ingredients needed is the availability of well-planned and well-managed industrial parks with Congratulations to the Malaysian Investment eco-friendly features. Thus, it is of paramount importance Development Authority (MIDA) and the for park developers and relevant authorities to work Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers together in developing the next generation of industrial (FMM) for the successful organisation of areas to cater for the whole value chain of the respective the Industrial Park Forum nationwide last industry, from upstream to downstream. -

Global Practice in Incubation Policy Development and Implementation

Global Practice in Incubation Policy Development and Implementation Malaysia Incubation Country Case Study Global Good Practice in Incubation Policy Development and Implementation Malaysia Incubation Country Case Study October 2010 ©2010 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are entirely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of infoDev, the Donors of infoDev, the International Bank for Recon- struction and Development/ The World Bank and its affiliated organizations, the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank cannot guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply on the part of the World Bank any judgment of the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permis- sion to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete infor- mation to infoDev Communications & Publications Department., 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue NW; Mailstop F 5P-503, Washington, D.C. -

PHARMACEUTICAL Industry in MALAYSIA

Guide on PHARMACEUTICAL Industry in MALAYSIA Kuala Lumpur Malaysia Your Profit Centre in Asia MALAYSIAN INVESTMENT DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY www.mida.gov.my Preface This guidebook for the pharmaceutical industry in Malaysia serves as an important source of information for investors intending to invest in this industry. It also spells out the procedures and requirements for the various applications for licences and permits for the setting up of a business in the pharmaceutical industry. The Malaysian Investment Development Authority (MIDA) is the Government’s principal agency under the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) responsible for the promotion and coordination of industrial development in Malaysia. MIDA assists companies which intend to invest in the manufacturing and services sectors in the country. MIDA has a global network of 20 overseas offices covering North America, Europe and Asia Pacific to assist investors. Within Malaysia, MIDA has 12 branch offices in the various states to facilitate investors in the implementation and operation of their projects. For more information on investment opportunities in Malaysia and contact details of MIDA, visit www.mida.gov.my. Published by MALAYSIAN INVESTMENT DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY Contents Fact Sheet of Malaysia 2 - Background of Malaysia - Key Economic Indicators - Healthcare in Malaysia Status of Industry 4 - The Pharmaceutical Industry in Malaysia - Investment Opportunities Why Malaysia 6 The Costs of Doing Business in Malaysia 7 - Starting a Business - Taxation Infrastructure -

Literature Review

From a Capital City to a World City: Vision 2020, Multimedia Super Corridor and Kuala Lumpur A thesis presented to the faculty of the Center for International Studies of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Jen Yih Yap August 2004 This thesis entitled From A Capital City to A World City: Vision 2020, Multimedia Super Corridor and Kuala Lumpur BY JEN YIH YAP has been approved for the Program of Southeast Asian Studies and the Center for International Studies by __________________________________________________ Yeong-Hyun Kim Assistant Professor of Geography __________________________________________________ Josep Rota Associate Provost, Center for International Studies YAP, JEN YIH. M. A. August 2004. Southeast Asian Studies From A Capital City to A World City: Vision 2020, Multimedia Super Corridor and Kuala Lumpur (121pp.) Advisor of Thesis: Yeong-Hyun Kim In 1991, the former Prime Minister Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad introduced an initiative called Vision 2020, designed to bring Malaysia to a developed country status, and this initiative will eventually support Kuala Lumpur’s position to become a world city. This thesis examines the recent urban restructuring of Kuala Lumpur in terms of the Malaysian government’s current aspiration for world city status. Many capital cities in the developing world have been undergoing various world city projects that aim at, among other things, improving their international visibility, advancing urban infrastructures and promoting economic competitiveness in a global world economy. This thesis focuses on four large-scale constructions in the Multimedia Super Corridor, namely, the Kuala Lumpur City Center, Kuala Lumpur International Airport, Putrajaya and Cyberjaya. -

Template for for the Jurnal Teknologi

Jurnal Full Paper Teknologi TECHNOLOGY PARKS OF INDONESIA, Article history Received MALAYSIA, AND SINGAPORE: A CRITICAL 30 July 2015 Received in revised form DISCOURSE 30 September 2015 Accepted N., Baluch*, C. S., Abdullah, R., Abidin 31 October 2015 School of Technology Management & Logistics, College of *Corresponding author Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia, 06010 Sintok, Kedah, Malaysia [email protected] Graphical Abstract Abstract The emergence of global scale competition is leading towards the development of new mechanisms to help countries to become more competitive and technology parks are the vehicle of choice to achieve that. Technology Parks offer modern infrastructure and integrated info-structure to promote research and technology development and commercialization for wealth creation and sustainable economic growth and Global Competitiveness. This paper discusses the position of technology parks in East Asia; elaborates on their role in today’s nation development, analytically examines three selected technology parks in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore using GCI Index 2015 and concludes that Technology parks have contributed to gross domestic product (GDP) growth, infrastructure development, knowledge community expansion, capacity building, and export production and distribution. However, optimum benefits of Technology Parks accrue when they are established and managed professionally in line with the best practices and all transactions are equitable, just, and transparent; the whole process must culminate trust -

Computing, Technology & Games Development

COMPUTING, TECHNOLOGY & GAMES DEVELOPMENT i can transform passion into action @ APU COMPUTING, TECHNOLOGY & GAMES DEVELOPMENT INNOVATIVE THINKING CAN CHANGE YOUR WORLD IN PARTNERSHIP INSPIRING YOU TOWARDS EXCELLENCE & DIGITAL FUTURE IT STARTS NOW....... IT STARTS HERE COMPUTING, TECHNOLOGY & GAMES DEVELOPMENT APU COMPUTING & IT PROGRAMMES PROGRAMMES BSc (Hons) in Information Technology BSc (Hons) in Information Technology with a specialism in: - Information System Security - Database Administration - Cloud Computing - Network Computing - Mobile Technology - Business Information Systems - Internet of Things (IoT) BSc (Hons) in Computer Science BSc (Hons) in Computer Science with a specialism in Data Analytics BSc (Hons) in Software Engineering BSc (Hons) in Intelligent Systems BSc (Hons) in Internet Technology BSc (Hons) in Multimedia Technology BSc (Hons) in Computer Games Development BSc (Hons) in Computer Games Development with a specialism in Games Concept Art APIIT 3+0 UK DEGREE PROGRAMMES (Awarded by Staffordshire University) BSc (Hons) Business Information Technology BSc (Hons) Cyber Security BSc (Hons) Forensic Computing APU among the Highest Rated Universities in Malaysia Being rated at TIER 5 (EXCELLENT) under the SETARA 2011 Ratings by the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) and Malaysian Qualifications Agency (MQA), and has maintained this Excellent rating in the latest SETARA 2013 Ratings announced on 17th November 2014. COMPUTING, TECHNOLOGY & GAMES DEVELOPMENT 3 : Why Us APIIT amongst the Highest Rated Colleges APU amongst the Highest Rated Universities Asia Pacific University of Technology & Innovation (APU) is amongst Malaysia’s Premier Private Universities, and is where a unique fusion of technology, innovation and creativity works effectively towards preparing professional graduates for significant roles in business and society globally. -

SK One E-Brochurev2 13

URBAN LIVING WITH THE COMFORTS OF HOME AN EXCELLENT LOCATION To KL To KL N Seri Petaling LRT Station Bukit Jalil LRT Station INTERNATIONAL BUKIT JALIL STADIUM Astro MEDICAL UNIVERSITY BUKIT JALIL HIGHWAY PERSIARAN SERDANG PERDANA Novelle Hotel TECHNOLOGY PARK MALAYSIA Mobil PALACE OF THE GOLDEN PERSIARAN PUNCAK JALIL MAJU EXPRESSWAY JALAN UTAMA McDonald’s HORSES Taman Seri Kembangan Puncak Jalil South New Village City Plaza THE MINES JALAN BESAR To Kajang Caltex SERI KEMBANGAN SILK HIGHWAY SALES GALLERY Serdang GPS 3.019129, 101.704146 KTM Station SUNGAI BESI HIGHWAY PUSAT Public Bank Taman Taman PERDAGANGAN Serdang Lestari Equine SERI Petronas Jaya Perdana KEMBANGAN HIGHWAY NORTH-SOUTH Alice Smith International Taman School Universiti Indah AEON UNIVERSITY Taman PUTRA MALAYSIA Putra Permai To Puchong/ Proposed SKIP LDP/ SKVEJALAN PUTRAGIANT PERMAI Highway & Interchange To Putrajaya To Seremban Shopping Malls Educations Bank Highways Aeon University Putra Malaysia Public Bank Bukit Jalil Highway Artist’s Impression only Giant Alice Smith International School Maju Expressway The Mines International Medical University Others North - South Highway 429 units freehold South City Plaza Astro Sungai Besi Highway Landmarks McDonald’s SILK Highway Hotels Bukit Jalil Stadium Novelle Hotel Technology Park Malaysia Palace Of The Golden Horses DESIGNED FOR MODERN LIVING Built on 3.4 acres of freehold land, SK One Residence comprises 2 residential towers on top of a multi-level podium with 24-hour security system. A well-thought-out design that will accommodate all your exquisite lifestyle needs. Artist’s Impression only 1. LEGEND 15. 1. Games Room 10. Wading Pool 2. 2. Nursery 11. Jacuzzi 14. -

Astro Malaysia Holdings Berhad (“Amh” Or “The Company”)

ASTRO MALAYSIA HOLDINGS BERHAD (“AMH” OR “THE COMPANY”) 6TH ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING The Audited Financial Statements for the financial year ended 31 January 2018 and the Reports of the Directors and Auditors thereon were received and duly tabled at the 6th Annual General Meeting (“AGM”) under Agenda 1. The following Resolutions as set out in the Notice of the 6th AGM dated 8 May 2018 and the Circular to Shareholders dated 8 May 2018 were duly passed at the 6th AGM:- Ordinary Business Ordinary Declaration of a Final Single-Tier Dividend of 0.5 sen per ordinary share for the financial Resolution 1 year ended 31 January 2018. Ordinary Re-election of Datuk Yvonne Chia as a Director of the Company pursuant to Article 111 Resolution 2 of the Company’s Articles of Association. Ordinary Re-election of Tun Dato’ Seri Zaki bin Tun Azmi as a Director of the Company pursuant Resolution 3 to Article 111 of the Company’s Articles of Association. Ordinary Re-election of Renzo Christopher Viegas as a Director of the Company pursuant to Resolution 4 Article 118 of the Company’s Articles of Association. Ordinary Re-election of Shahin Farouque bin Jammal Ahmad as a Director of the Company Resolution 5 pursuant to Article 118 of the Company’s Articles of Association. Ordinary Approval of Payment of Directors’ Fees and Benefits for the period from 8 June 2018 Resolution 6 until the next Annual General Meeting of the Company to be held in 2019:- Type of Fees/Benefits Amount (RM) Board Chairman 520,000 per annum Non-Executive Director 280,000 per annum Audit and Risk Committee . -

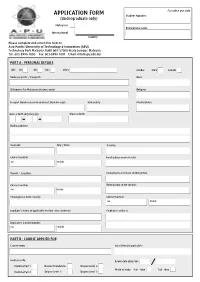

APPLICATION FORM Student Number: (Undergraduate Only)

For office use only APPLICATION FORM Student Number: (Undergraduate only) Malaysian Programme code: International Country Please complete and return this form to: Asia Pacific University of Technology & Innovation (APU) Technology Park Malaysia, Bukit Jalil, 57000 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Tel : 603-8996 1000 Fax: 603-8996 1001 Email: [email protected] PART A : PERSONAL DETAILS Title: Mr Ms Mrs Other Gender: Male Female Name (as per IC / Passport): Race: IC Number (For Malaysian Students only): Religion: Passport Number (For International Students only): Nationality: Marital Status: Date of birth (dd/mm/yy): Place of birth: Mailing Address Postcode: City / State: Country: Contact number: Email (please write clearly): Tel Mobile Parent / Guardian: Contact person in Case of Emergency: Contact number: Relationship to the student: Tel Mobile Email (please write clearly): Contact number: Tel Mobile Employer’s Name (if applicable for Part -Time students): Employer’s address: Employer’s Contact number: Tel Mobile PART B : COURSE APPLIED FOR Course name: Specialism (if applicable): Level of study: Intake date (mm/yy): Diploma Part 1 Degree Foundation Degree Level 2 Mode of study: Part - time Full - time Diploma Part 2 Degree Level 1 Degree Level 3 PART C : ACADEMIC BACKGROUND (from highest to lowest) Please list in chronological order all secondary and tertiary studies completed. Please attach a copy of your certificates and the transcripts of all results obtained for your highest level of study, plus a certified translation if the originals are not in English. Qualification: Name of School / College / University: Year completed: Result: Actual Forecast PART D : MEDICAL DISCLOSURE Do you have any medical condition that requires the attention of the University? If yes, please indicate below: Allergies Anaemia Asthma Colour Blindness Epilepsy Heart Disease Others (please give details): Note (for International Students Only): 1. -

CYBERJAYA Global Technology Hub Blueprint INTRODUCTION

CYBERJAYA Global Technology Hub Blueprint INTRODUCTION The Global Technology Hub Blueprint study was commissioned to carve out the technology strength in Malaysia, to be strategically developed and to strengthen its core competency for innovative technology development within Cyberjaya. The development of specific technology focus is to consolidate key resources and distinctive capabilities of Cyberjaya, for developing new opportunities to invoke and foster innovative values in technology as a driver for the country. The study undertook benchmarking of the best technology parks and start-up ecosystems across the globe that played a pivotal role in the success of their own technology driven economies. This strategic approach brings to light a broader perspective in using global practices to work with various agencies across the ecosystem. This includes collaborative industry partnership and commercialisation in the technology value chain of Malaysia. The blueprint provides a conceptual framework to evaluate the impact of innovation and technology at a global level; to benchmark local technology integration competency and a yardstick for resources efficiency to develop a competitive edge for achieving the digital aspirations of Malaysia No part of this document may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission of Cyberview Sdn Bhd (CSB). This document has been compiled for the exclusive use of the Global Technology Hub committee and stakeholders and is not complete without the underlying detail analyses and the oral presentation. CSB does not assume any responsibility for the completeness and accuracy of the statements made in this document. © 2014 by Cyberview Sdn Bhd. -

Promoting Knowledge Transfer in Science and Technology: a Case Study of Technology Park Malaysia (TPM)

Promoting Knowledge Transfer in CORE Science and Technology: A CaseMetadata, Study citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk of Technology Park Malaysia (TPM) Abd Hair Awang* ** Mohd Yusof Hussain *** Jalaluddin Abdul Malek Abstract Knowledge transfer can be defined as a process of knowledge creation and application, knowledge mobilization and exchange, information search and transformation as well as the learning process at and outside the workplace. The success of companies in a knowledge-based economy relies more on knowledge and intellectual capital than on other resources. Therefore, transferring new knowledge from foreign multinational corporations (MNC) to the local workforce is a basic step for sustaining competitive advantages. Success in knowledge transfer depends on employee absorption capacities, organizational learning climate, and the willingness of foreign expatriates in MNCs to transfer knowledge. Using the case study of Technology Park Malaysia (TPM), this paper investigates to what extent knowledge inflows and outflows have taken place among the professional Malaysian workforce. It also analyzes the factors influencing knowledge transfer. Keywords: knowledge transfer, organizational learning, employee absorption capacities JEL classification: D83, O14, O31, O32 * Abd Hair Awang, Center of Social, Development and Environmental Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, National University of Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia, e-mail: hairukm.my. ** Mohd Yusof Hussain, Center of Social, Development and Environmental -

Promoting Knowledge Transfer in Science and Technology: a Case Study of Technology Park Malaysia (TPM)

Promoting Knowledge Transfer in Science and Technology: A Case Study of Technology Park Malaysia (TPM) Abd Hair Awang* ** Mohd Yusof Hussain *** Jalaluddin Abdul Malek Abstract Knowledge transfer can be defined as a process of knowledge creation and application, knowledge mobilization and exchange, information search and transformation as well as the learning process at and outside the workplace. The success of companies in a knowledge-based economy relies more on knowledge and intellectual capital than on other resources. Therefore, transferring new knowledge from foreign multinational corporations (MNC) to the local workforce is a basic step for sustaining competitive advantages. Success in knowledge transfer depends on employee absorption capacities, organizational learning climate, and the willingness of foreign expatriates in MNCs to transfer knowledge. Using the case study of Technology Park Malaysia (TPM), this paper investigates to what extent knowledge inflows and outflows have taken place among the professional Malaysian workforce. It also analyzes the factors influencing knowledge transfer. Keywords: knowledge transfer, organizational learning, employee absorption capacities JEL classification: D83, O14, O31, O32 * Abd Hair Awang, Center of Social, Development and Environmental Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, National University of Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia, e-mail: hairukm.my. ** Mohd Yusof Hussain, Center of Social, Development and Environmental Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, National