Transcript of an Audio Interview with Professor Salima

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Withheld File 2020 Dividend D-8.Xlsx

LOTTE CHEMICAL PAKISTAN LIMITED FINAL DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2020 @7.5% RSBOOK CLOSURE FROM 14‐APR‐21 TO 21‐APR‐21 S. NO WARRANT NO FOLIO NO NAME NET AMOUNT PAID STATUS REASON 1 8000001 36074 MR NOOR MUHAMMAD 191 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 2 8000002 47525 MS ARAMITA PRECY D'SOUZA 927 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 3 8000003 87080 CITIBANK N.A. HONG KONG 382 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 4 8000004 87092 W I CARR (FAR EAST) LTD 191 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 5 8000005 87094 GOVETT ORIENTAL INVESTMENT TRUST 1,530 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 6 8000006 87099 MORGAN STANLEY TRUST CO 976 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 7 8000007 87102 EMERGING MARKETS INVESTMENT FUND 96 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 8 8000008 87141 STATE STREET BANK & TRUST CO. USA 1,626 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 9 8000009 87147 BANKERS TRUST CO 96 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 10 8000010 87166 MORGAN STANLEY BANK LUXEMBOURG 191 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 11 8000011 87228 EMERGING MARKETS TRUST 58 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 12 8000012 87231 BOSTON SAFE DEPOSIT & TRUST CO 96 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 13 8000017 6 MR HABIB HAJI ABBA 0 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 14 8000018 8 MISS HISSA HAJI ABBAS 0 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 15 8000019 9 MISS LULU HAJI ABBAS 0 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 16 8000020 10 MR MOHAMMAD ABBAS 18 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 17 8000021 11 MR MEMON SIKANDAR HAJI ABBAS 12 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 18 8000022 12 MISS NAHIDA HAJI ABBAS 0 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 19 8000023 13 SAHIBZADI GHULAM SADIQUAH ABBASI 792 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 20 8000024 14 SAHIBZADI SHAFIQUAH ABBASI -

FRIDAY 16Th NOVEMBER 2018

FAIZ INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL 16th – 18th November 2018 Alhamra Halls, Mall Road Lahore All events are free and open for all (Except for Tahira Syed, Tina Sani and Zia Mohyeddin performances) FRIDAY 16th NOVEMBER 2018 Hall 1 Hall 2 Gallery 4:00 – 4:45 pm ک یفی اور فی ض Shabana Azmi, Salima Hashmi (Adeel Hashmi & Mira Hashmi) Exhibition Opening 4:00 – 6:30 5:00-6:00 pm 5:00 pm Preparation Time Preparation Time 6:30 – 7:30 pm 6:00 – 7:00 pm زرد پتوں کا بن جو میرا د یس ہے Guests to be Seated Guests to be Seated 7:00 – 9:00 pm 7:30 – 9:00 pm بھ ُ کاﻻ م ینڈا یس یاد کی راہ گزر A Play by Ajoka Theatre An Evening with Tahira Syed Dedicated to Madeeha Gohar Note: Please download latest copy of the schedule nearer to the Festival as slight changes are expected. SATURDAY 17th NOVEMBER 2018 Time Hall 1 Hall 2 Hall 3 Gallery Adbi Baithak Exhibition Area Master Class on Screen Writing ت ت am 11:00 خواب کی ت لی کے ی چھے Javed Akhtar 12:00 pm (Adeel Hashmi) A performance by Sanjan Nagar Students Meet Uncle Sargam: A Conversation with نور کی لہر ق ق (Over My Shoulder (Alys Faiz ساق تا ر ص کوئی ر ِص ص تا صورت pm 12:00 Blurring the Boundaries: Imaging the Film Farooq Qaiser 12:45 pm Dance Performance Nayyar Rubab (Translator) Salima Hashmi, Imran Abas (Arshad Mehmood) (Lahore Grammar School) (Dr Sheeba Alam) (Mira Hashmi) َ Space, Place & Art: A Discussion on Art for Public ا تا لی ہوس والوں نے خو رسم چلی ہے ح ب عن یر د ت ت ب ی ِ س Spaces & People Patras Bukhari: A Friend, Diplomat, Teacher & Writer ,Natasha Jozi, Rabeya Jalil سمی دی وار صحافت م یں س ناست -

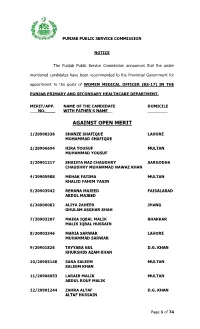

Against Open Merit

PUNJAB PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION NOTICE The Punjab Public Service Commission announces that the under mentioned candidates have been recommended to the Provincial Government for appointment to the posts of WOMEN MEDICAL OFFICER (BS-17) IN THE PUNJAB PRIMARY AND SECONDARY HEALTHCARE DEPARTMENT. MERIT/APP. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE DOMICILE NO.____ WITH FATHER'S NAME ________ AGAINST OPEN MERIT 1/20900338 SHANZE SHAFIQUE LAHORE MOHAMMAD SHAFIQUE 2/20906694 HIRA YOUSUF MULTAN MUHAMMAD YOUSUF 3/20901217 SHAISTA NAZ CHAUDHRY SARGODHA CHAUDHRY MUHAMMAD NAWAZ KHAN 4/20905988 MEHAK FATIMA MULTAN KHALID FAHIM YASIN 5/20903942 REHANA MAJEED FAISALABAD ABDUL MAJEED 6/20900082 ALIYA ZAHEER JHANG GHULAM ASGHAR SHAH 7/20903207 MAIRA IQBAL MALIK BHAKKAR MALIK IQBAL HUSSAIN 8/20903346 MARIA SARWAR LAHORE MUHAMMAD SARWAR 9/20901826 TAYYABA GUL D.G. KHAN KHURSHID AZAM KHAN 10/20905148 SARA SALEEM MULTAN SALEEM KHAN 11/20906053 LARAIB MALIK MULTAN ABDUL ROUF MALIK 12/20901244 ZAHRA ALTAF D.G. KHAN ALTAF HUSSAIN Page 1 of 74 From Pre-page 1315 posts of Women Medical Officer (BS-17) in the Punjab Primary & Secondary Healthcare Department MERIT/APP. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE DOMICILE NO.__ WITH FATHER'S NAME ________ 13/20903132 ZAHRA MUSHTAQ RAWALPINDI MUHAMMAD MUSHTAQ AHMAD 14/20901604 MARIA FATIMA OKARA QURBAN ALI 15/20901854 HAFIZA AMMARA SIDDIQI FAISALABAD MUHAMMAD SIDDIQUE 16/20904115 QURAT-UL-AIN SARWAR LAHORE MANZOOR SARWAR CHAUDHARY 17/20901733 AALIA BASHIR D.G. KHAN SHEIKH DAUD ALI 18/20905234 FARVA KOMAL M. GARH GHULAM HAIDER KHAN 19/20901333 SADIA MALIK SARGODHA GHULAM MUHAMMAD 20/20904405 ZARA MAHMOOD RAWALPINDI MAHMOOD AKHTER 21/20900565 MARIA IRSHAD HAFIZABAD IRSHAD ULLAH 22/20902101 FARYAL ASIF SARGODHA ASIF ILYAS 23/20901525 MAHAM FATIMA M. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

Koppal-Davanagere-Tumkur- Approved List Bidaai-201920

Bidaai-201920 Koppal-Davanagere-Tumkur- Approved List REG NAME OF THE Name of the Account SL.NO. TALUK Holder Amount NO BENEFICIARY Father/Mother 1 79/2018-19 Gangavthi KHAJABNI KHAJABANI 25000 2 92/208-19 KOPPAL YASMEEN SHAHAJADIBI 25000 3 128/18-19 KOPPAL ASMA BEGUM SHAHIDA BEGUM 25000 4 82/18-19 KOPPAL MABOOBI RAMJA BEE 25000 5 76/18-19 KOPPAL RIZVANA KHAM SALIMA BEGAM 25000 6 78/18-19 KOPPAL RESHMA MODINA BI 25000 7 88/18-19 KOPPAL BIBI ASHIYA BEGUM BIBI BEGUM K HABEEBA 25000 8 83/19-19 KOPPAL MARDAN BEE IMAMSAB 25000 9 99/18-19 KOPPAL AYISHA BANU NILOFAR 25000 10 107/18-19 KOPPAL YASMEEN BANU BI 25000 11 129/18-19 KOPPAL CHAND BI IMAM SAB 25000 12 122/18-19 KOPPAL TASLEEM BANU SHAKILA BANU 25000 13 85/18-19 KOPPAL RUKSANA PIRAMBI 25000 14 101/18-19 KOPPAL YASMEEN BANU JAIRABEE GUDDADAR 25000 15 115/18-19 KOPPAL SANIHA TABASUM SANIHA TABASSUM 25000 16 127/18-19 KOPPAL HEENA TAZ BABUSAB DAMBAL 25000 17 96/18-19 KOPPAL RUBIYA BEGUM SHAHAJAD BEGUM 25000 18 108/18-19 KOPPAL SABEEHA BANU KHAJABANI MAJEERA 25000 19 89/2018-19 KOPPAL RUKSHANA BEGUM Rukshana Begum 25000 20 120/2018-19 KOPPAL NISHAMA FATHIMA Raheema Begum 25000 21 136/2018-19 KOPPAL Ashabee KHAJA BEE 25000 MAMTAJBI BASHUSAB 22 80/2018-19 KOPPAL Sabina Begum 25000 VALIKAR 23 106/2018-19 KOPPAL Yasmeen Kasim Sab 25000 24 79/2018-19 KOPPAL Mohaseena Nafees Hafiza bi 25000 25 84/2018-19 KOPPAL Navina Begum Mabusab Yenni 25000 26 91/2018-19 KOPPAL Shamina Begum Fathimabi 25000 27 132/2018-19 KOPPAL Yasmeen Arifa Begum 25000 28 121/2018-19 KOPPAL Parveen Mamataj Begum 25000 29 134/2018-19 -

Newsletter July 2018 | Issue 25 | Half Yearly

NEWSLETTER JULY 2018 | ISSUE 25 | HALF YEARLY Celebrating 35 Years of Excellence in Mental Health Care CEO’s Message I am pleased to present the Newsletter of Karwan- free of cost treatment, has set an example for many to follow. e-Hayat with great happiness. This year, we are The last six months have been very busy, crowded as they were with celebrating Karwan’s 35 years of excellence in a number of events, workshops, fundraisers, awareness sessions, mental health care. Karwan-e-Hayat has been at the zakat campaign and most of all the 1st International Conference on forefront in redefining and introducing innovative Psychosocial & Psychiatric Rehabilitation, which was a huge success. practices through which mental healthcare is I am thankful to all the supporters, employees and friends of Karwan provided to the people of Pakistan. Our successful without whom this success would not have been possible. I wish you all model of being a network of paperless hospitals, providing happy reading and a prosperous year ahead and hope for your continued indiscriminate quality mental healthcare and above all providing 90% support. Thank you Zaheeruddin Babar Yadain Karwan’s Annual Fundraising Event This year Karwan’s annual Fundraiser was on 17th & 18th February 2018, at The Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, where renowned artist, Humaira Channa, performed on two magical musical evenings of songs and ghazal. She sang ghazals of legends like Madam Noor Jehan, Mehdi Hasan, Farida Khanum, Ahmed Rushdi and many more. The show was hosted by well-known music composer, artist and friend of Karwan, Mr. -

Bilingual / Bi-Annual Pakistan Studies, English / Urdu Research Journal

I ISSN: 2311-6803 PAKISTAN STUDIES Bilingual / Bi-annual Pakistan Studies, English / Urdu Research Journal Vol. 03 Serial No. 1 January - June 2016 Editor: Dr.Mohammad Usman Tobawal PAKISTAN STUDY CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF BALOCHISTAN, QUETTA. II III MANAGING COMMITTE Patron Prof. Dr. Javaid Iqbal Vice Chancellor Editor Inchief Prof. Dr. Naheed Anjum Chishti Editor Dr. Muhammad Usman Tobawal Assistant Editors Dr. Noor Ahmed Prof. Dr. Kalimullah Prof. Dr. Ain ud Din Prof. Ghulam Farooq Baloch Prof. Yousuf Ali Rodeni Prof. Surriya Bano Associate Editors Prof. Taleem Badshah Mr. Qari Abdul Rehman Miss. Shazia Jaffar Mr. Nazir Ahmed Miss. Sharaf Bibi Composing Section Mr. Manzoor Ahmed Mr. Bijar Khan Mr. Pervaiz Ahmed IV EDITORIAL BOARD INTERNATIONAL Dr. Yanee Srimanee, Ministry of Commerce, Thailand. Prof. M. Aslam Syed Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Dr. Jamil Farooqui Dept. of Sociology and Anthropology, International Islamic University, Kaula Lumpur Prof. Dr. Shinaz Jindani, Savannah State University of Georgia, USA Dr. Elina Bashir, University of Chicago. Dr. Murayama Kazuyuki, #26-106, Hamahata 5-10, Adachi-ku, Tokyo 1210061, Japan. Prof. Dr. Fida Muhammad, State University of New York Oneonta NY 12820 Dr. Naseer Dashti, 11 Sparows Lane, New Elthaw London, England SEQ2BP. Dr. Naseeb Ullah, International Correspondent, Editor & Political Consultant, The Montreal Tribune, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Johnny Cheung Institute of Culture & Language Paris, France. V EDITORIAL BOARD NATIONAL Prof. Dr.Abdul Razzaq Sabir, Vice Chancellor, Turbat University. Dr. Fakhr-ul-Islam University of Peshawar. Dr. Abdul Saboor Pro Vice Chancellor, University of Turbat. Syed Minhaj ul Hassan, University of Peshawar. Prof. Dr. Javaid Haider Syed, Gujrat University. -

Research and Development

Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT FACULTY OF ARTS & HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY Projects: (i) Completed UNESCO funded project ―Sui Vihar Excavations and Archaeological Reconnaissance of Southern Punjab” has been completed. Research Collaboration Funding grants for R&D o Pakistan National Commission for UNESCO approved project amounting to Rs. 0.26 million. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE & LITERATURE Publications Book o Spatial Constructs in Alamgir Hashmi‘s Poetry: A Critical Study by Amra Raza Lambert Academic Publishing, Germany 2011 Conferences, Seminars and Workshops, etc. o Workshop on Creative Writing by Rizwan Akthar, Departmental Ph.D Scholar in Essex, October 11th , 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, University of the Punjab, Lahore. o Seminar on Fullbrght Scholarship Requisites by Mehreen Noon, October 21st, 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, Universsity of the Punjab, Lahore. Research Journals Department of English publishes annually two Journals: o Journal of Research (Humanities) HEC recognized ‗Z‘ Category o Journal of English Studies Research Collaboration Foreign Linkages St. Andrews University, Scotland DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE R & D-An Overview A Research Wing was introduced with its various operating desks. In its first phase a Translation Desk was launched: Translation desk (French – English/Urdu and vice versa): o Professional / legal documents; Regular / personal documents; o Latest research papers, articles and reviews; 39 Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development The translation desk aims to provide authentic translation services to the public sector and to facilitate mutual collaboration at international level especially with the French counterparts. It addresses various businesses and multi national companies, online sales and advertisements, and those who plan to pursue higher education abroad. -

Greenwich Earns the Most Exculsive Awards Banking Future Lies in Islamic Banking Muhammad Raza Head of Consumer Banking & Marketing Meezan Bank

Vol. XIII, Issue III - ISSN 2305-7947 Winter Semester 2013-2014 A Quarterly Periodical of Greenwich Earns the Most Exculsive Awards Banking Future Lies in Islamic Banking Muhammad Raza Head of Consumer Banking & Marketing Meezan Bank “Smart Thinking Can Lead To Success” Karim Ismail Teli Director, Orient Textile & Ibrahim Group of Companies Greenwich Alumnus Dear Readers, It gives us immense pleasure and joy to see G.Vision take its final shape at the com - pletion of another successful semester: Winter 2013-14.We can look at it and say that it’s an accomplished piece of work. This issue of G-Vision highlights an environ - ment of innovation and several significant events around Greenwich campus as we continue to evolve and grow. It is indeed a matter of great pride to be the editor of an issue where the cover story is all about the unwavering efforts, hard work and dedication of our Vice Chancel - lor and her entire team. Our cover story shines with Greenwich being the first ever EDITORIAL BOARD HEC recognized university to achieve the most prestigious awards namely The Brand of the Year Award and The Brand Scientist Award. Patron It is best said that “life is a succession of lessons which must be lived to be under - stood”. Life is an informal school. Each day we have an opportunity to learn. In this Ms Seema Mughal process of trial and error emerges the process of growth. Vice Chancellor Keeping this in mind I believe we have succeeded in putting together a well- Editor rounded, enjoyable memento for everybody. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2008 the Management Team Is Also Being Trained on Various Basel II Requirements

Contents Corporate Information......................................................................01 Director’s Report to the Shareholders........................................02 Statement of Compliance with the Code of Corporate Governance.......................................................07 Statement of Internal Control........................................................09 Notice of Annual General Meeting...........................................10 Review Report to the Members on Statement of the Compliance with Best Practices of Code of Corporate Governance...................................................................12 Auditor’s Report to Members.......................................................13 Balance Sheet......................................................................................15 Profit and Loss Account..................................................................16 Cash Flow Statement.......................................................................17 Statement Of Changes In Equity................................................18 Notes to Financial Statements.....................................................19 Six Years Key financial Data...........................................................62 Annexure - 1.........................................................................................63 Combined Pattern of CDC and Physical Share Holdings...................................................................64 Combined Pattern of CDC and Physical Share Holdings ..................................................................65 -

Year 2018-19

Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi List of Students Department Wise/State Wise/Gender Wise For Session Jul/2018 - Dec/2018,Jul/2018 - Jun/2019 AND Jan/2018 - Dec/2018 Run Date : 12/02/2020 Department :ALL Admission Type : ALL S.No. State/Country Gender S.No. Student ID Name Category Course 1 Andhra Pradesh Female 1 20175620 Gulafsha Fatima Muslim Women M.A./M.Sc. Mathematics( Self Finance) - II Yr. 2 20173501 Afreen Sheikh Muslim M.A.(Mass Communication)(Semester) - III Sem. 3 20185044 Aseya Fatima Muslim Women B.Tech.(Computer Engineering)(Semester) - I Sem. 4 20172098 Intifada P.B. Muslim Women M.A.(Convergent Journalism)(Semester Self Finance) - III Sem. Male 5 20182188 Qureshi Asif Ali Muslim OBC/Muslim ST M.A.(History)(Semester) - I Sem. 6 20182861 Ismail Shaik Arifulla Muslim B.A. (H) Arabic(Semester) - I Sem. 7 20181456 Mohammed Feroz Muslim M.A.(Conflict Analysis & Peace Building)(Semester) - I Sem. 8 20177481 Shaik Mohammed Muslim OBC/Muslim ST B.Tech.(Mechanical Muaviya Engineering)(Semester) - III Sem. 9 20181401 Abdul Khadar Muslim B.Ed. - I Yr. 10 20186322 Saidheeraj General M.A.(Economics)(Semester) - I Vayugundlachenchu Sem. 11 20157693 Mohammed Omar NRI ward under B.Tech.(Electrical Siddiqui Supernumeray category Engineering)(Semester) - VII Sem. 12 20159109 Venkata Saibabu General Ph.D.(Bio Science)(Semester) Thokala 13 20172111 Bhanu Prasad Palanati General M.Ed.(Special Education)(Semester) - III Sem. 14 20174688 Fakruddin Mohammed Muslim M.A.(Islamic Studies)(Semester) Ali Halaharvi - III Sem. 15 20177060 Abdul Sofiyan Muslim M.A.(Political Science)(Semester) - III Sem. 16 20148252 C. -

PRINT CULTURE and LEFT-WING RADICALISM in LAHORE, PAKISTAN, C.1947-1971

PRINT CULTURE AND LEFT-WING RADICALISM IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN, c.1947-1971 Irfan Waheed Usmani (M.Phil, History, University of Punjab, Lahore) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and it has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information which have been used in the thesis. This thesis has also not been submitted for any degree in any university previously. _________________________________ Irfan Waheed Usmani 21 August 2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First I would like to thank God Almighty for enabling me to pursue my higher education and enabling me to finish this project. At the very outset I would like to express deepest gratitude and thanks to my supervisor, Dr. Gyanesh Kudaisya, who provided constant support and guidance to this doctoral project. His depth of knowledge on history and related concepts guided me in appropriate direction. His interventions were both timely and meaningful, contributing towards my own understanding of interrelated issues and the subject on one hand, and on the other hand, injecting my doctoral journey with immense vigour and spirit. Without his valuable guidance, support, understanding approach, wisdom and encouragement this thesis would not have been possible. His role as a guide has brought real improvements in my approach as researcher and I cannot measure his contributions in words. I must acknowledge that I owe all the responsibility of gaps and mistakes in my work. I am thankful to his wife Prof.