Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik™S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Debate Over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue

Jack Wertheimer (ed.) The American Synagogue: A Sanctuary Transformed. New York: Cambridge 13 University Press, 1987 The Debate over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue JONATHAN D. SARNA "Pues have never yet found an historian," John M. Neale com plained, when he undertook to survey the subject of church seating for the Cambridge Camden Society in 1842. 1 To a large extent, the same situation prevails today in connection with "pues" in the American syn agogue. Although it is common knowledge that American synagogue seating patterns have changed greatly over time - sometimes following acrimonious, even violent disputes - the subject as a whole remains unstudied, seemingly too arcane for historians to bother with. 2 Seating patterns, however, actually reflect down-to-earth social realities, and are richly deserving of study. Behind wearisome debates over how sanctuary seats should be arranged and allocated lie fundamental disagreements over the kinds of social and religious values that the synagogue should project and the relationship between the synagogue and the larger society that surrounds it. As we shall see, where people sit reveals much about what they believe. The necessarily limited study of seating patterns that follows focuses only on the most important and controversial seating innovation in the American synagogue: mixed (family) seating. Other innovations - seats that no longer face east, 3 pulpits moved from center to front, 4 free (un assigned) seating, closed-off pew ends, and the like - require separate treatment. As we shall see, mixed seating is a ramified and multifaceted issue that clearly reflects the impact of American values on synagogue life, for it pits family unity, sexual equality, and modernity against the accepted Jewish legal (halachic) practice of sexual separatiop in prayer. -

Half the Hanukkah Story Rabbi Norman Lamm Chancellor and Rosh Hayeshiva, Yeshiva University

Half the Hanukkah Story Rabbi Norman Lamm Chancellor and Rosh HaYeshiva, Yeshiva University This drasha was given by Rabbi Lamm in the Jewish Center in NYC on Shabbat Chanuka, December 23, 1967. Courtesy of Rabbi Lamm and the Yad Lamm online drasha archiveof the Yeshiva University Museum. Two Themes of Hanukkah Two themes are central to the festival of Hanukkah which we welcome this week. They are, first, the nes milhamah, the miraculous victory of the few over the many and the weak over the strong as the Jews repulsed the Syrian-Greeks and reestablished their independence. The second theme is the nes shemmen, the miracle of the oil, which burned in the Temple for eight days although the supply was sufficient for only one day. The nes milhamah represents the success of the military and political enterprise of the Macabeeans, whilst the nes shemmen symbolizes the victory of the eternal Jewish spirit. Which of these is emphasized is usually an index to one’s Weltanschauung. Thus, for instance, secular Zionism spoke only of the nes milhamah, the military victory, because it was interested in establishing the nationalistic base of modern Jewry. The Talmud, however, asking, "What is Hanukkah?," answered with the nes shemmen, with the story of the miracle of the oil. In this way, the Rabbis demonstrated their unhappiness with the whole Hasmonean dynasty, descendants of the original Macabees who became Saducees, denied the Oral Law, and persecuted the Pharisees. Yet, it cannot be denied that both of these themes are integral parts of Judaism. Unlike Christianity, we never relegated religion to a realm apart from life; we never assented to the bifurcation between that which belongs to God and that which belongs to Ceasar. -

1 Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos

Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos: Some Tentative Thoughts David Berger The deep and systemic tension between contemporary egalitarianism and many authoritative Jewish texts about gentiles takes varying forms. Most Orthodox Jews remain untroubled by some aspects of this tension, understanding that Judaism’s affirmation of chosenness and hierarchy can inspire and ennoble without denigrating others. In other instances, affirmations of metaphysical differences between Jews and gentiles can take a form that makes many of us uncomfortable, but we have the legitimate option of regarding them as non-authoritative. Finally and most disturbing, there are positions affirmed by standard halakhic sources from the Talmud to the Shulhan Arukh that apparently stand in stark contrast to values taken for granted in the modern West and taught in other sections of the Torah itself. Let me begin with a few brief observations about the first two categories and proceed to somewhat more extended ruminations about the third. Critics ranging from medieval Christians to Mordecai Kaplan have directed withering fire at the doctrine of the chosenness of Israel. Nonetheless, if we examine an overarching pattern in the earliest chapters of the Torah, we discover, I believe, that this choice emerges in a universalist context. The famous statement in the Mishnah (Sanhedrin 4:5) that Adam was created singly so that no one would be able to say, “My father is greater than yours” underscores the universality of the original divine intent. While we can never know the purpose of creation, one plausible objective in light of the narrative in Genesis is the opportunity to actualize the values of justice and lovingkindness through the behavior of creatures who subordinate themselves to the will 1 of God. -

Theological Affinities in the Writings of Abraham Joshua Heschel and Martin Luther King, Jr.*

Theological Affinities in the Writings of Abraham Joshua Heschel and Martin Luther King, Jr.* Susannah Heschel T he photograph of Abraham Joshua Heschel walking arm in arm with Mar tin Luther King, Jr. in the front row of marchers at Selma has become an icon of American Jewish life, and of Black-Jewish relations. Reprinted in Jewish textbooks, synagogue bulletins, and in studies of ecumenical relations, the pic ture has come to symbolize the great moment of symbiosis of the two commu nities, Black and Jewish, which today seems shattered. When Jesse Jackson, Andrew Young, Henry Gates, or Cornel West speak of the relationship between Blacks and Jews as it might be, and as they wish it would become, they invoke the moments when Rabbi Heschel and Dr. King marched arm in arm at Selma, prayed together in protest at Arlington National Cemetery, and stood side by side in the pulpit of Riverside Church. The relationship between the two men began in January 1963, and was a genuine friendship of affection as well as a relationship of two colleagues working together in political causes. As King encouraged Heschel’s involve ment in the Civil Rights movement, Heschel encouraged King to take a pub lic stance against the war in Vietnam. When the Conservative rabbis of Amer ica gathered in 1968 to celebrate HeschePs sixtieth birthday, the keynote speaker they invited was King. Ten days later, when King was assassinated, Heschel was the rabbi Mrs. King invited to speak at his funeral. 126 Susannah Heschel 127 What is considered so remarkable about their relationship is the incon gruity of Heschel, a refugee from Hitler’s Europe who was born into a Hasidic rebbe’s family in Warsaw, with a long white beard and yarmulke, involving himself in the cause of Civil Rights. -

Kol Hamevaser 2.1:Torahumadah.Qxd

Kol Hamevaser Contents Volume 2, Issue 1 Staff September 20, 2008 Managing Editors Alex Ozar 3 Editorial: On Selihot Ben Kandel Rabbi Shalom Carmy 4-5 On Optimism and Freedom: A Preface to Rav Gilah Kletenik Kook’s Orot Ha-Teshuvah Alex Ozar Emmanuel Sanders 6-7 Levinas and the Possibility of Prayer Shaul Seidler-Feller Ari Lamm 7-9 An Interview with Rabbi Hershel Reichman Staff Writers Rena Wiesen 9-10 Praying with Passion Ruthie Just Braffman Gilah Kletenik 10 The Supernatural, Social Justice, and Spirituality Marlon Danilewitz Simcha Gross 11 Lions, Tigers, and Sin - Oh My! Ben Greenfield Noah Greenfield Ruthie Just Braffman 12 Lord, Get Me High Simcha Gross Joseph Attias 13 Finding Meaning in Teshuvah Emmanuel Sanders Devora Stechler Rena Wiesen Special Features Interviewer Ari Lamm Gilah Kletenik 14-15 Interview with Rabbi Marc Angel on His Recently Published Novel, The Search Committee Typesetters Yossi Steinberger Aryeh Greenbaum Upcoming Issue In the spirit of the current political season and in advance of the pres- idential elections, the upcoming edition of Kol Hamevaser will be on Layout Editor the topic of Politics and Leadership. The topic burgeons with poten- Jason Ast tial, so get ready to write, read, and explore all about Jews, Politics, and Leadership. Think: King Solomon, the Israel Lobby, Jewish Sovereignty, Exilarchs, Art Editor Rebbetsins, Covenant and Social Contract, Tzipi Livni, Jewish non- Avi Feld profits, Serarah, Henry Kissinger, the Rebbe, Va'ad Arba Aratsot, and much more! About Kol Hamevaser The deadline for submissions is October 12, 2008. the current editors of Kol Hamevaser would like to thank and applaud our outgoing editors, David Lasher and Mattan Erder, Kol Hamevaser is a magazine of Jewish thought dedicated to spark- as well as Gilah Kletenik and Sefi Lerner for their efforts to- ing the discussion of Jewish issues on the Yeshiva University campus. -

DAVID-HARTMAN-Edited.Pdf

Passover, Rabbi Prof. David Hartman wrote in 2010, is meant to celebrate and sustain our deep yearning for freedom, not necessarily to show that God can change the order of the universe. Passover is a holiday that inculcates the belief that man will overcome oppression, that freedom will reign throughout the world. The faith that tyranny will ultimately be vanquished is deeply embedded in the significance of Passover. By DAVID HARTMAN 1931-2013 …Coupled with the concerns about food, Passover suggests a supernatural model of redemption, which posits that God will break into history and save us just as He did during the Exodus from Egypt. Rather than give weight to our own personal will, responsibility and moral agency, this theological worldview says that the best we can hope for is that God will look down and have mercy on us. It is a way of understanding the holiday that positions us as passive and patient, waiting for an interventionist God to rescue us from our galut (Def: Jewish Diaspora) realities. Does this truly reflect what Passover is about? A memory of miracles? An obsession with rituals? Whatever happened to the dramatic, overarching themes of freedom from oppression, self-governance, and spiritual rebirth? In search of a little religious sobriety, I recently began revisiting the work of Mordechai Kaplan, the great 20th century Jewish thinker and founder of the Reconstructionist movement. The crucial question for Kaplan is how do the commandments percolate into the lifestream of the Jewish people? How do the rituals shape us ethically? How do the mitzvot propel us to become full human beings and reach our powers of ethical personality? In other words, how does Judaism impact us in the quest for human self-realization? Kaplan’s philosophy grew out of his quest to understand how the Jewish people created patterns of living with the potential to redeem us from selfishness, narcissism, cruelty, and open us to a world of holiness. -

This Inspiring and Eminently Readable Book by John C

“This inspiring and eminently readable book by John C. Merkle, Heschel’s leading Christian interpreter, provides a lucid introduction to the Jewish thinker and activist’s God-centered thought. Written with earnestness, analytical subtlety, and faith, Approaching God demonstrates how Heschel’s radical interpretations of traditional Judaism can favor theological humility, religious diversity, and interfaith dialogue.” — Edward K. Kaplan Kaiserman Professor in Humanities, Brandeis University Author of Spiritual Radical: Abraham Joshua Heschel in America “John Merkle has pondered the thought of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel for many years. In Approaching God, Merkle provides readers with a discerning analysis of the wisdom of this eminent religious figure. Those who follow Merkle’s sensitive exploration of Heschel will partake of this wisdom themselves.” — Mary C. Boys, S.N.J.M. Skinner and McAlpin Professor of Practical Theology, Union Theological Seminary Author of Has God Only One Blessing? Judaism as a Source of Christian Self-Understanding “John Merkle has produced a first-class study of the life and writings of Abraham Joshua Heschel, a man who has deeply influenced today’s generation of theologians. Merkle has engaged thoughtfully with Heschel’s approach to the divine-human encounter and Approaching God will be welcomed by Jews and Christians alike. Readers of this work are extremely fortunate to benefit from the author’s lifelong interest in Heschel. The book not only provides an insight into this hugely significant Jewish theologian but also offers profound wisdom on the spiritual journey, daily undertaken by each and everyone of us.” — Edward Kessler Executive Director, Woolf Institute of Abrahamic Faiths, Cambridge, England Author of What Do Jews Believe? “Here is a lucid, powerful, and beautiful guide to one of the most compelling theolo- gians of our time. -

Annual Report 2012

SHaloM HartMan Institute 2 012 ANNUAL REPORT תשעב - תשעג SHaloM HartMan Institute 2 012 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL REPORT 2 012 Developing Transformative Ideas: Kogod Research Center for Contemporary Jewish Thought 11 Research Teams 12 Center Fellows 14 iEngage: The Engaging Israel Project at the Shalom Hartman Institute 15 Beit Midrash Leadership Programs 19 Department of Publications 20 Annual Conferences 23 Public Study Opportunities 25 Strengthening Israeli-Jewish Identity: Center for Israeli-Jewish Identity 27 Be’eri Program for Jewish-Israeli Identity Education 28 Lev Aharon Program for Senior Army Officers 31 Model Orthodox High Schools 32 Hartman Conference for a Jewish-Democratic Israel 34 Improving North American Judaism Through Ideas: Shalom Hartman Institute of North America 37 Horizontal Approach: National Cohorts 39 Vertical Regional Presence: The City Model 43 SHI North America Methodology: Collaboration 46 The Hartman Community 47 Financials 2012 48 Board of Directors 50 ] From the President As I look back at 2012, I can do so only through the prism of my father’s illness and subsequent death in February 2013. The death of a founder can create many challenges for an institution. Given my father’s protracted illness, the Institute went through a leadership transition many years ago, and so the general state of the Institute is strong. Our programs in Israel and in North America are widely recognized as innovative and cutting-edge, and both reach and affect more people than ever before; the quality of our faculty and research and ideas instead of crisis and tragedy? are internationally recognized, and they Well, that’s iEngage. -

Rabbi Asher Schechter Study (718) 591-4888 Fax (718) 228-8677 Email [email protected]

CONGREGATION OHR MOSHE In Memory of Rav Moshe Feinstein ZT"L 170-16 73rd Avenue Hillcrest, NY 11366 (718) 591-4888 Rabbi Asher Schechter Study (718) 591-4888 Fax (718) 228-8677 Email [email protected] Dear Friends, This letter certifies that all items sold on the BAGEL BOSS WEBSITE are strictly Kosher. The bagels, rolls, challahs, challah rolls and other bread products are PARVE & PAS YISROEL, all other products are ASSUMED DAIRY (either dairy ingredients or dairy utensils) unless a label discloses otherwise. Any questions should be directed to me (contact information above). The following Bagel Boss locations are under my Supervision: Bagel Boss of Carle Place Bagel Boss of East Northport Bagel Boss of Hewlett Bagel Boss of Hicksville Bagel Boss of Jericho* Bagel Boss of Lake Success Bagel Boss of Manhattan (1st Ave.) Bagel Boss of Merrick Bagel Boss of Murray Hill, NYC (3rd Ave.) Bagel Boss of Oceanside Bagel Boss of Roslyn* All these locations mentioned above are owned and operated by Non-Jewish Owners/Partners for Shabbos & Yom Tov. The bagels, rolls, challahs, challah rolls and other bread products baked at these locations (except those with *) are PARVE & PAS YISROEL. All products are assumed DAIRY, unless a sign or label discloses otherwise. All Dairy products are assumed to be Non-Cholov-Yisrael except in Bagel Boss of Manhattan as described in detail in its Certification Letter. Off premises parties are generally not under my Supervision, unless special arrangements are made. .which coincides with September 19, 2020 ראש השנה תשפ"א This letter is valid through With Torah Greetings, Rabbi Asher Schechter AS/tf. -

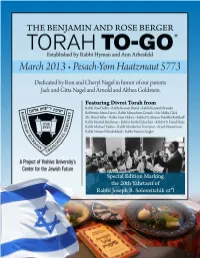

Pesach to Go - 5773.Pdf

1 Yeshiva University • The Benjamin and Rose Berger Torah To-Go Series• Nissan 5773 Richard M. Joel, President, Yeshiva University Rabbi Kenneth Brander, The David Mitzner Dean, Center for the Jewish Future Rabbi Joshua Flug, General Editor Rabbi Michael Dubitsky, Editor Andrea Kahn, Copy Editor Copyright © 2013 All rights reserved by Yeshiva University Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future 500 West 185th Street, Suite 413, New York, NY 10033 • [email protected] • 212.960.5263 This publication contains words of Torah. Please treat it with appropriate respect. For sponsorship opportunities, please contact Genene Kaye at 212.960.0137 or [email protected]. 2 Yeshiva University • The Benjamin and Rose Berger Torah To-Go Series• Nissan 5773 Table of Contents Pesach/Yom Haatzmaut 2013/5773 Rabbi Akiva’s Seder Table: An Introduction Rabbi Kenneth Brander . Page 7 Reflections on Rav Soloveitchik zt"l Growing up in Boston An Interview with Rebbetzin Meira Davis . Page 11 Insights into Pesach On the Study of Haggadah: A Note on Arami Oved Avi and Biblical Intertextuality Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik zt"l . Page 15 Use of the Term Makom, Omnipresent, in the Haggadah Rabbi Yosef Adler . Page 19 What Is Judaism? Rabbi Reuven Brand . Page 21 Why Don’t We Recite Shehecheyanu on Sefiras ha-Omer Rabbi Menachem Genack . Page 29 The Dual Aspect of the Four Cups: A Core Idea of Pesach from the Rav zt”l Rabbi Hershel Reichman . Page 33 Charoses: Why Don’t we Recite a Beracha? Rabbi Hershel Schachter . Page 35 Insights from the Rav on the “Maggid” Section of the Haggadah Rabbi Michael Taubes . -

Mahzor - Fourth Edition.Indb 1 18-08-29 11:38 Mahzor

Mahzor - Fourth Edition.indb 1 18-08-29 11:38 Mahzor. Hadesh. Yameinu RENEW OUR DAYS A Prayer-Cycle for Days of Awe Edited and translated by Rabbi Ron Aigen Mahzor - Fourth Edition.indb 3 18-08-29 11:38 Acknowledgments and copyrights may be found on page x, which constitutes an extension of the copyright page. Copyright © !""# by Ronald Aigen Second Printing, !""# $ird Printing, !""% Fourth Printing, !"&' Original papercuts by Diane Palley copyright © !""#, Diane Palley Page Designer: Associès Libres Formatting: English and Transliteration by Associès Libres, Hebrew by Resolvis Cover Design: Jonathan Kremer Printed in Canada ISBN "-$%$%$!&-'-" For further information, please contact: Congregation Dorshei Emet Kehillah Synagogue #( Cleve Rd #!"" Mason Farm Road Hampstead, Quebec Chapel Hill, CANADA NC !&)#* H'X #A% USA Fax: ()#*) *(%-)**! ($#$) $*!-($#* www.dorshei-emet.org www.kehillahsynagogue.org Mahzor - Fourth Edition.indb 4 18-08-29 11:38 Mahzor - Fourth Edition.indb 6 18-08-29 11:38 ILLUSTRATIONS V’AL ROSHI SHECHINAT EL / AND ABOVE MY HEAD THE PRESENCE OF GOD vi KOL HANSHEMAH T’HALLEL YA / LET EVERYTHING THAT HAS BREATH PRAISE YOU xxii BE-ḤOKHMAH POTE‘AḤ SHE‘ARIM / WITH WISDOM YOU OPEN GATEWAYS 8 ELOHAI NESHAMAH / THE SOUL YOU HAVE GIVEN ME IS PURE 70 HALLELUJAH 94 ZOKHREINU LE-ḤAYYIM / REMEMBER US FOR LIFE 128 ‘AKEDAT YITZḤAK / THE BINDING OF ISAAC 182 MALKHUYOT, ZIKHRONOT, SHOFAROT / POWER, MEMORY, VISION 258 TASHLIKH / CASTING 332 KOL NIDREI / ALL VOWS 374 KI HINNEI KA-ḤOMER / LIKE CLAY IN THE HAND OF THE POTIER 388 AVINU MALKEINU -

Modern Orthodoxy and the Road Not Taken: a Retrospective View

Copyrighted material. Do not duplicate. Modern Orthodoxy and the Road Not Taken: A Retrospective View IRVING (YITZ) GREENBERG he Oxford conference of 2014 set off a wave of self-reflection, with particu- Tlar reference to my relationship to and role in Modern Orthodoxy. While the text below includes much of my presentation then, it covers a broader set of issues and offers my analyses of the different roads that the leadership of the community and I took—and why.1 The essential insight of the conference was that since the 1960s, Modern Orthodoxy has not taken the road that I advocated. However, neither did it con- tinue on the road it was on. I was the product of an earlier iteration of Modern Orthodoxy, and the policies I advocated in the 1960s could have been projected as the next natural steps for the movement. In the course of taking a different 1 In 2014, I expressed appreciation for the conference’s engagement with my think- ing, noting that there had been little thoughtful critique of my work over the previous four decades. This was to my detriment, because all thinkers need intelligent criticism to correct errors or check excesses. In the absence of such criticism, one does not learn an essential element of all good thinking (i.e., knowledge of the limits of these views). A notable example of a rare but very helpful critique was Steven Katz’s essay “Vol- untary Covenant: Irving Greenberg on Faith after the Holocaust,” inHistoricism, the Holocaust, and Zionism: Critical Studies in Modern Jewish Thought and History, ed.