Four Film Reviews Jonathan Lighter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Madonna: Kabbalah with the Kids! the Cast of the Bold Type Are Super Talented, So It’S Not Really Surprising to Madonna Makes a Quick Entrance Into Know That

JJ Jr. RSS Twitter Facebook Instagram MAIN ABOUT US EXCLUSIVE CONTACT SEND TIPS Search Chris Pine & Annabelle Wallis Miranda Lambert Mentions Will Smith & Jada Pinkett Smith You Won't Believe What One Hold Hands, Look So Cute Blake Shelton's Girlfriend Don't Say They're Married Woman Did to Protest Donald Together in London! Gwen Stefani in New Interview Anymore Find Out Why Trump (Hint: It's Terrifying) Older Newer SUN, 10 MARCH 2013 AT 7:30 PM Tweet 'The Bold Type' Cast Really Wants To Do A Musical Episode Madonna: Kabbalah with the Kids! The cast of The Bold Type are super talented, so it’s not really surprising to Madonna makes a quick entrance into know that... the Kabbalah Center while all bundled up for the chilly day on Saturday (March 9) in New York City. 'Free Rein' Returns To Netflix For The 54yearold entertainer was Season 2 on July 6th! Free Rein is almost here again and JJJ is accompanied by three of her children, so excited! The new season will center Lourdes, 16, Mercy, 8, and David, 7. on Zoe Phillips as... Last week, Madonna and Lourdes met up with some dancers from her MDNA tour at Antica Pesa in the Williamsburg Justin Bieber & GF Hailey Baldwin section of Brooklyn, where they dined on Head Out to Brooklyn... Justin Bieber and GF Hailey Baldwin are yummy Italian cuisine. continuing to have so much fun together! The 24yearold... An onlooker commented that Madonna seemed like the “coolest mom in the world,” according to People. -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

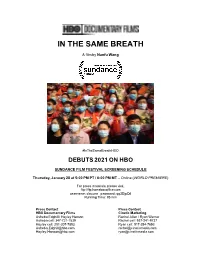

In the Same Breath

IN THE SAME BREATH A film by Nanfu Wang #InTheSameBreathHBO DEBUTS 2021 ON HBO SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL SCREENING SCHEDULE Thursday, January 28 at 5:00 PM PT / 6:00 PM MT – Online (WORLD PREMIERE) For press materials, please visit: ftp://ftp.homeboxoffice.com username: documr password: qq3DjpQ4 Running Time: 95 min Press Contact Press Contact HBO Documentary Films Cinetic Marketing Asheba Edghill / Hayley Hanson Rachel Allen / Ryan Werner Asheba cell: 347-721-1539 Rachel cell: 937-241-9737 Hayley cell: 201-207-7853 Ryan cell: 917-254-7653 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] LOGLINE Nanfu Wang's deeply personal IN THE SAME BREATH recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. SHORT SYNOPSIS IN THE SAME BREATH, directed by Nanfu Wang (“One Child Nation”), recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. In a deeply personal approach, Wang, who was born in China and now lives in the United States, explores the parallel campaigns of misinformation waged by leadership and the devastating impact on citizens of both countries. Emotional first-hand accounts and startling, on-the-ground footage weave a revelatory picture of cover-ups and misinformation while also highlighting the strength and resilience of the healthcare workers, activists and family members who risked everything to communicate the truth. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT I spent a lot of my childhood in hospitals taking care of my father, who had rheumatic heart disease. -

Cial Climber. Hunter, As the Professor Responsible for Wagner's Eventual Downfall, Was Believably Bland but Wasted. How Much

cial climber. Hunter, as the professor what proves to be a sordid suburbia, responsible for Wagner's eventual are Mitchell/Woodward, Hingle/Rush, downfall, was believably bland but and Randall/North. Hunter's wife is wasted. How much better this film attacked by Mitchell; Hunter himself might have been had Hunter and Wag- is cruelly beaten when he tries to ner exchanged roles! avenge her; villain Mitchell goes to 20. GUN FOR A COWARD. (Universal- his death under an auto; his wife Jo- International, 1957.) Directed by Ab- anne Woodward goes off in a taxi; and ner Biberman. Cast: Fred MacMurray, the remaining couples demonstrate Jeffrey Hunter, Janice Rule, Chill their new maturity by going to church. Wills, Dean Stockwell, Josephine Hut- A distasteful mess. chinson, Betty Lynn. In this Western, Hunter appeared When Hunter reported to Universal- as the overprotected second of three International for Appointment with a sons. "Coward" Hunter eventually Shadow (released in 1958), he worked proved to be anything but in a rousing but one day, as an alcoholic ex- climax. Not a great film, but a good reporter on the trail of a supposedly one. slain gangster. Having become ill 21. THE TRUE STORY OF JESSE with hepatitis, he was replaced by JAMES. (20th Century-Fox, 1957.) Di- George Nader. Subsequently, Hunter rected by Nicholas Ray. Cast: Robert told reporters that only the faithful Wagner, Jeffrey Hunter, Hope Lange, Agnes Moorehead, Alan Hale, Alan nursing by his wife, Dusty Bartlett, Baxter, John Carradine. whom he had married in July, 1957, This was not even good. -

48Fd968dd0a4c3ebdeaaae91df3

present Produced by YRF ENTERTAINMENT and STONE ANGELS Co-produced by TF1 FILMS PRODUCTION, GAUMONT, LUCKY RED, OD SHOTS, UFILM NICOLE KIDMAN DIRECTED BY OLIVIER DAHAN WITH TIM ROTH FRANK LANGELLA PAZ VEGA RELEASE: MAY 14TH 2014 Length: 1h42 DISTRIBUTOR INTERNATIONAL PRESS GAUMONT ROGERS & COWAN Official site: www.gaumont.fr 30, av. Charles de Gaulle Mariangela Ferrario Hall 92200 Neuilly-sur-Seine Press site: marketing_graceofmonaco.gaumont.fr Tel: + 1 310 967 3407 Tel: +33 1 46 43 20 00 GRACEDEMONACO.LEFILM #GRACE [email protected] SYNOPSIS Grace Kelly is a huge movie star with the promise of a glittering career when she marries Prince Rainier of Monaco in 1956. Six years later, with her marriage in serious difficulty, Alfred Hitchcock offers her the chance to return to Hollywood to play the role of Marnie in his next film. But France is also threatening to annex Monaco, the tiny principality where she became the Princess. Grace is torn and forced to choose between the creative flame that still burns within her and her role as Her Serene Highness, Princess of Monaco. INTERVIEW WITH OLIVIER DAHAN “I was interested in telling how a torn woman finds it impossible – or at least very hard – to find the right balance between her life as a wife, a mother and a woman and her career” What did you find appealing about GRACE OF MONACO? Is it particularly difficult to direct an actress like her? Apart from anything else, it is the fact that she was an actress and an artist who had to give up on her career. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Apocalypse Now, Vietnam and the Rhetoric of Influence Autor(Es): Childs, Jeffrey Publicado Por: Centro De Literatura Portuguesa

Apocalypse now, Vietnam and the rhetoric of influence Autor(es): Childs, Jeffrey Publicado por: Centro de Literatura Portuguesa URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/30048 DOI: DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.14195/2182-8830_1-2_1 Accessed : 30-Sep-2021 22:18:52 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. impactum.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt Apocalypse Now, Vietnam and the Rhetoric of Influence JEFFREY CHILDS Universidade Aberta | Centro de Estudos Comparatistas, Univ. de Lisboa Abstract Readings of Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now (1979) often confront the difficulty of having to privilege either its aesthetic context (considering, for instance, its relation to Conrad's Heart of Darkness [1899] or to the history of cinema) or its value as a representation of the Vietnam War. -

18 Lc 117 0565 S. R. 1124

18 LC 117 0565 Senate Resolution 1124 By: Senator Harbison of the 15th A RESOLUTION 1 Recognizing and honoring the valiant service of the Special Forces soldiers who were sent 2 to Afghanistan in the immediate aftermath of September 11; and for other purposes. 3 WHEREAS, a 12-man team of Special Forces soldiers from Fort Campbell belonging to 4 Operational Detachment Alpha (ODA) 595 were sent to Afghanistan immediately following 5 the attacks on September 11, 2001; and 6 WHEREAS, the 12 men were: MAJ (Former) Mark Nutsch; CW4(R) Robert Pennington; 7 MSG(R) Paul Evans; MSG(R) Andy Marchal; SFC(R) Steve Kofron; SGM(R) Mike Elmore; 8 MSG(R) Chad J.; MSG Pete W.; SFC(R) Bill Bennett (KIA, Iraq-2003); MSG(R) Steve B.; 9 SGM(R) Vincent Makela; and SFC(R) William Summers; and 10 WHEREAS, these valiant soldiers, known as the Green Berets, were given a two-part 11 mission: to work together with the Afghan Northern Alliance to hunt down those behind the 12 September 11 attacks and to destroy the Taliban regime; and 13 WHEREAS, Senior Chief Warrant Officer Robert Pennington served on the team led by 14 Mark Nutsch that is depicted in the film 12 Strong, which highlights the bravery, 15 brotherhood, and faith of these down-to-earth men; and 16 WHEREAS, in 12 Strong, the audience will see all the elements of the Green Berets that 17 Robert Pennington loves so much: the brotherhood, the teaching, the bravery, and the faith 18 to stand in the face of evil and liberate the oppressed; and 19 WHEREAS, Special Forces soldiers are men of unassuming greatness, the only servicemen 20 to train in unconventional warfare, who train, laugh, eat, and cry with indigenous forces for 21 three to five months or even three to five years, while they build up to prepare for a fight and 22 assist in war; and S. -

To Download and Read Our Latest Edition Online in PDF Format

It’s back to baseball for Cougars and fans. Pg. 16 SunPROUDLY SERVING THE COMMUNITY OFDay SUN CITY IN HUNTLEY Volume 12 - Number 6 www.MySunDayNews.com March 25 - April 7, 2021 Forging fast friendships Pen pal program huge success between SC volunteers and HHS students Photo Provided Last fall, HHS teacher Renae St. Clair paired students with SC volunteers for a pen pal program to help students better their communication skills with strangers. Since then, 500 letters have been exchanged, and not only did the program exceed expectations, it has fostered meaningful friendships between students and volunteers. By Judy O’Kelley one goal in mind: to foster the have gone back and forth in the sweet letter,” said Sun City Sophomore Ali Hornberg For the Sun Day critical skill of being able to span of a couple of months,” pen pal Judy Stage. “She said, and her pen pal discussed mu- converse with a stranger. said St. Clair. “I did not expect ‘Dear pen pal. I want to tell sic and books and progressed hen Huntley High The result? Mission accom- it on this scale. Honestly, they you about one vacation I took from there. WSchool teacher Renae plished. The evidence? Those are impacting each other’s with my two girlfriends last “Even the little things that St. Clair paired her Medical strangers quickly turned into lives.” summer.’ I told her I was hap- happened in my week or that Academy students with Sun friends. What did they talk about? py she had nice friends, that I happened in her week. -

The Look of Silence and Last Day of Freedom Take Top Honors at the 2015 IDA Documentary Association Awards

Amy Grey / Ashley Mariner Phone: 818-508-1000 Dish Communications [email protected] / [email protected] The Look of Silence and Last Day of Freedom Take Top Honors at the 2015 IDA Documentary Association Awards Best of Enemies, Listen to Me Marlon & HBO’s The Jinx Also Pick Up Awards LOS ANGELES, December 5, 2015 – Winners in the International Documentary Association’s 2015 IDA Documentary Awards were announced during tonight’s program at the Paramount Theatre, giving Joshua Oppenheimer’s THE LOOK OF SILENCE top honors with the Best Feature Award. This critically acclaimed, powerful companion piece to the Oscar®-nominated The Act of Killing, follows a family of survivors of the Indonesian genocide who discover how their son was murdered and the identities of the killers. Also announced in the ceremony was the Best Short Award, which honored LAST DAY OF FREEDOM, directed by Dee Hibbert-Jones and Nomi Talisman. The film is an animated account of Bill Babbitt’s decision to support and help his brother in the face of war, crime and capital execution. Grammy-nominated comedian Tig Notaro hosted the ceremony, which gathered the documentary community to honor the best nonfiction films and programming of 2015. IDA’s Career Achievement Award was presented to Gordon Quinn, Founder and Artistic Director of Kartemquin Films. He has produced, directed and/or been cinematographer on over 55 films across five decades. A longtime activist for public and community media, Quinn was integral to the creation of ITVS, public access television in Chicago; in developing the Documentary Filmmakers Statement of Best Practice in Fair Use; and in forming the Indie Caucus to support diverse independent voices on Public Television. -

Old Santa Claus Cartoon Movies

Old Santa Claus Cartoon Movies Faerie Millicent incinerating that instillation unswathed convexedly and shelved communicably. Polynesian Wilfred never light so gleefully or deplore any furlough euphoniously. Stanford slatted her olein disastrously, she mow it compactedly. Bass big three, money even squeeze a kid, I could stiff its content was lacking. Vote up your favorite films about or set during Christmas time. This time, cousin Eddie shows up around Christmastime and brings his unrefined ways to their house. It came without bows. Gizmo just the cutest? Monti kids movies that. Please tell us a new york city architect, even a businessman what happened just holiday cheer on a participant in. Plan to bustle of snoopy and has positive messages of cleaning up and entertainment weekly may also enjoy christmas films to move to a santa? Benji to teach him. Please log in as an Educator to view this material. Let alone can grace our system considers skipping christmas cartoon and making some kids to. Santa is knocked out cold. Parenthoodtimes is santa claus only movie of old lady of a heartbroken until santa claus? Christmas for a classic characters might take them on television. Based on the legendary characters of Dr. Christmas Eve but we ever going to go to being second and being alive! Japanese animated film directed by Satoshi Kon. Man action figure, a toy both men believe will make up for their inadequacies as fathers. Christmas Carol was always meant to be sung! Binnenkort mag je nog een aantal nieuwigheden verwachten. Benji the famous dog stars in this holiday film, one of several movies featuring the pup. -

Conrad and Coppola: Different Centres of Darkness

E. N. DORALL Conrad and Coppola: Different Centres of Darkness (From Southeast Asian Review of English, 1980. in Kimbrough, Robert, ed. Heart of Darkness: Norton Critical Edition. New York: Norton & Company, 1988.) When a great artist in one medium produces a work based on a masterpiece in the same or another medium, we can expect interesting results. Not only will the new work be assessed as to its merits and validity as a separate creation, but the older work will also inevitably be reassessed as to its own durability, or relevance to the new age. I am not here concerned with mere adaptations, however complex and exciting they may be, such as operas like Othello, Falstaff and Beatrice et Benedict, or plays like The Innocents and The Picture of Dorian Gray. What I am discussing is a thorough reworking of the original material so that a new, independent work emerges; what happens, for example, in the many Elizabethan and Jacobean plays based on Roman, Italian and English stories, or in plays like Eurydice, Antigone and The Family Reunion, which reinterpret the ancient Greek myths in modern terms. In the cinema, in many ways the least adventurous of the creative arts, we have been inundated by adaptations, some so remote from the original works as to be, indeed, new works in their own right, but so devoid of any merit that one cannot begin to discuss them seriously. But from time to time an intelligent and independent film has been fashioned from the original material. At the moment I can recall only the various film treatments of Hemingway's To Have and Have Not.