IASCP Paper June 1996

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sluttstilling Etter Finale

G-Sport/Jakt & Friluft Cup 2013 - Resultat etter finale Plass Id Navn Klasse Forening Grunnlag kvalifiseringen Sum Finale Totalt 1 1453838 Bilben, Hans A Kvam JFF 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 200 23 25 248 2 275027 Meier, Johnny A Nidaros JSK 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 200 23 24 247 e.o. 3 1481746 Jonsen, Roy Arne A Heidal JFF 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 200 23 24 247 e.o. 4 258401 Falldalen, Terje E1 Romedal & Vallset JFF 25 25 25 25 25 25 24 24 198 25 24 247 e.o. 5 1515746 Kveum, Håkon A Sel JFF 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 200 25 21 246 e.o. 6 1680101 Hippe, Kåre Bjørsrud A Nord-Aurdal JFF 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 200 23 23 246 e.o. 7 1434141 Prestrud, Vidar B Nord-Aurdal JFF 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 200 23 23 246 e.o. 8 1620317 Kværna, Rune A B Øystre Slidre JFF 25 25 25 25 25 24 24 24 197 25 23 245 e.o. 9 127573 Wit, Johnny de A Biri JFF 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 24 199 22 24 245 e.o. 10 1567974 Grinden, Thore A Løiten JFF 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 24 199 23 23 245 e.o. 11 1580263 Moe, Morten A Øyer-Tretten JFF 25 25 25 25 25 25 24 24 198 24 22 244 11 1524747 Nordli, Knut A Løiten JFF 25 25 25 25 25 24 24 24 197 23 24 244 11 1668570 Rundhaug, Frode A Nordre Land JSK 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 200 22 22 244 11 1568015 Rønningen, Geir Asle A Gausdal JFF 25 25 25 25 25 24 24 24 197 24 23 244 11 1708206 Milsteinhaugen, Bjørn B Kvam JFF 25 25 25 25 24 24 24 24 196 24 24 244 11 1352773 Kildalen, Johnny C Romedal & Vallset JFF 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 24 199 22 23 244 17 1491446 Gulbrandsen, Jens Chr A Nord-Aurdal JFF 25 25 24 24 24 24 24 24 194 24 25 243 17 1605491 Kleiven, -

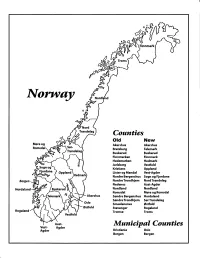

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

District 104 K.Pdf

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF MAY 2006 CLUB MMR MMR FCL YR OB MEMBERSHI P CHANGES TOTAL IDENT CLUB NAME DIST TYPE NBR RPT DATE RCV DATE NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERSH 3932 019519 ÅSNES 104 K 1 08-2005 09-07-2005 1 1 3932 019519 ÅSNES 104 K 1 09-2005 09-08-2005 3932 019519 ÅSNES 104 K 9 08-2005 09-28-2005 -1 -1 3932 019519 ÅSNES 104 K 1 12-2005 01-05-2006 3932 019519 ÅSNES 104 K 1 01-2006 01-05-2006 1 1 3932 019519 ÅSNES 104 K 1 02-2006 02-09-2006 3932 019519 ÅSNES 104 K 1 03-2006 03-09-2006 3932 019519 ÅSNES 104 K 9 03-2006 04-05-2006 3932 019519 ÅSNES 104 K 1 04-2006 04-05-2006 3932 019519 ÅSNES 104 K 1 05-2006 05-08-2006 34 2 0 0 -1 1 35 3932 019521 BRUMUNDDAL 104 K 1 07-2005 07-25-2005 -1 -1 3932 019521 BRUMUNDDAL 104 K 1 11-2005 11-20-2005 1 -2 -1 3932 019521 BRUMUNDDAL 104 K 1 10-2005 11-28-2005 1 1 3932 019521 BRUMUNDDAL 104 K 9 11-2005 11-28-2005 1 1 3932 019521 BRUMUNDDAL 104 K 1 02-2006 02-23-2006 48 2 1 0 -3 0 48 3932 019523 EIDSKOG 104 K 1 12-2004 08-21-2005 3932 019523 EIDSKOG 104 K 1 01-2005 08-21-2005 -1 -1 3932 019523 EIDSKOG 104 K 1 02-2005 08-21-2005 3932 019523 EIDSKOG 104 K 1 03-2005 08-21-2005 3932 019523 EIDSKOG 104 K 1 04-2005 08-21-2005 3932 019523 EIDSKOG 104 K 1 05-2005 08-21-2005 3932 019523 EIDSKOG 104 K 1 06-2005 08-21-2005 3 3 3932 019523 EIDSKOG 104 K 1 07-2005 09-21-2005 3932 019523 EIDSKOG 104 K 1 08-2005 09-21-2005 3932 019523 EIDSKOG 104 K 1 09-2005 09-21-2005 45 3 0 0 -1 2 47 3932 019524 ELVERUM 104 K 1 09-2005 09-13-2005 -

Pinsestevnet 2008 Lesja

Pinsestevnet 2008 Lesja Premieliste Mesterskap Klasse 3-5 1 Mikkel Voll Stokkli Rennebu 5 50 48 48 97 100 343 Medalje 2 Ivar Fivelstad Sunnylven 5 49 45 50 99 99 342 3 Tor Gaute Jøingsli Lom og Skjåk 5 50 47 50 95 97 339 4 Dick Brevik Engesetdal/Skodje 5 50 44 48 97 99 338 5 Odd Sverre Håkenstad Lesja 5 50 49 50 91 98 338 6 Otte Hårstad Rennebu 5 50 47 49 97 95 338 7 Gudbrand Mo Lom og Skjåk 5 49 45 47 98 98 337 8 Ådne Ø. Søyland Gjesdal 5 49 46 48 95 98 336 9 Einar Furuseth Aasveen 5 49 45 48 96 98 336 10 Stein Ove Robøle Øystre Slidre 4 49 42 49 97 96 333 11 Bjørn Lykken Beito 4 49 44 48 97 95 333 12 Ottar Dalset Rauma 5 50 43 47 95 98 333 13 Iva Hidemstrædet Vågå 4 50 46 50 92 95 333 14 Bernt Runde Isfjorden og Åndalsnes 4 48 47 49 89 98 331 15 Anders Kolrud Østre Gausdal 4 47 43 47 94 98 329 16 Trond Jøingsli Lom og Skjåk 4 48 47 47 91 91 324 17 Asbjørn Gussiås Nesjestranda og Skaala 4 46 42 50 92 93 323 18 Atle Bakken Vågå 3 47 40 45 89 99 320 19 Ola Venås Østre Gausdal 3 47 43 45 92 93 320 20 Jo Salthammer Vestnes skytterlag 4 49 41 48 86 94 318 21 Svend Bentdal Lesja 3 47 36 50 94 90 317 22 Per-Jarle Nerhus Vestnes skytterlag 3 50 41 47 82 95 315 23 Leif Arne Fivelstad Sunnylven 5 47 37 47 86 97 314 24 John Ola Selsjord Lesja 3 48 29 40 71 94 282 25 Mona Isene Rennebu 5 50 43 50 95 238 26 Odd Arild Stenstuen Vågå 4 49 44 47 96 236 26 Arne Erik Christophersen Aasveen 5 46 47 49 94 236 26 Henrik Aasveen Fåberg 5 50 42 47 97 236 29 Erik Nyseter Opdal 4 49 40 49 95 233 30 Tore Ølstad Lesja 3 47 45 47 89 228 31 Tore Hagestande Lesja -

Årgang 23 Årsskrift Frå Vågå Historielag Jutulen 2019

Jutulen 2019 Årgang 23 ÅrsskrifT frå Vågå HisTorielag Jutulen 2019 Årgang 23 ÅrsskrifT frå Vågå HisTorielag RedakTør: KnuT RaasTad Annonser: Dag Aasheim TilreTTeleggjing for Trykk: Visus, Lom Trykk: Dalegudbrands Trykkeri Vågå HisTorielag vil reTTe sTor Takk Til alle som har medverka Til uTgjeving av JuTulen 2019. STor Takk Til arTikkelforfaTTarane som har kome med inTeressanTe, lokalhisToriske arTiklar! Vidare går Takken Til dei som har lånT uT bileTe, Til annonsørane og elles andre som har gjeve god hjelp. Gjendesheim. Foto frå Ragnvald Berg, Vågå historielags fotoarkiv Framsida: Frå Gjendesheim. Heimreise frå arbeid på Gjendesheim og Gjendebu hausten 1953. F.v.: ukjent, Harald Ramen, Berit Frikstad Steineide, Anne Aabakken Hovden, Ragna Plassen, Aud Skogstad, Jens Skogstad, Kari Groven Skogstad, Jorun Kamhaugen Tho, Kristian Sveen, Marit Nesset Haugom, Ragnhild Skjellum, Jørgen Ødegård, Per Skjellum, Marit Kluften, Magnhild Skjellum, Ivar Sæte (sjåfør på bussen), Kari Skjellum. Foto frå Ragna Plassen, namna av Kari G Holen og Asbjørn Kvarberg. 2 Innhald Claus Krag: PorTreTTene av H.P.S. Krag og Hermana Krag side 4 KnuT RaasTad: RisgrauT som julekveldsmaT side 7 KnuT RaasTad: STorTingsmenn frå Vågå side 8 Helene Hovden: Frå SundsTugu Til Løvebakken side 15 Helene Hovden: JuleTrefesT i SundsTugu side 19 Eirik Haugen: Peder Knudsen Bakken, evnerik vagver side 20 Vegard Veierød: Kleber, skifer, kalksTein og kvernsTeinbrudd side 22 KnuT Ryen: ØrnbergeT i FinnfareT side 30 Arne Ryen. KveinnsTein frå Lalm side 32 Anmodning Til VelocipedryTTere -

Folketeljing 1910 for 0416 Romedal Digitalarkivet

Folketeljing 1910 for 0416 Romedal Digitalarkivet 08.09.2014 Utskrift frå Digitalarkivet, Arkivverkets teneste for publisering av kjelder på internett: http://digitalarkivet.no Digitalarkivet - Arkivverket Innhald Løpande liste ................................ 11 Førenamnsregister ...................... 163 Etternamnsregister ...................... 207 Fødestadregister .......................... 253 Bustadregister ............................. 263 4 Folketeljingar i Noreg Det er halde folketeljingar i Noreg i 1769, 1801, 1815, 1825, 1835, 1845, 1855, 1865, 1870 (i nokre byar), 1875, 1885 (i byane), 1891, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, 1946, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980 og 1990. Av teljingane før 1865 er berre ho frå i 1801 nominativ, dvs ho listar enkeltpersonar ved namn. Teljingane i 1769 og 1815-55 er numeriske, men med namnelistar i grunnlagsmateriale for nokre prestegjeld. Statistikklova i 1907 la sterke restriksjonar på bruken av nyare teljingar. Etter lov om offisiell statistikk og Statistisk Sentralbyrå (statistikklova) frå 1989 skal desse teljingane ikkje frigjevast før etter 100 år. 1910-teljinga vart difor frigjeven 1. desember 2010. Folketeljingane er avleverte til Arkivverket. Riksarkivet har originalane frå teljingane i 1769, 1801, 1815-1865, 1870, 1891, 1910, 1930, 1950, 1970 og 1980, mens statsarkiva har originalane til teljingane i 1875, 1885, 1900, 1920, 1946 og 1960 for sine distrikt. Folketeljinga 1. desember 1910 Ved kgl. Res. 23. september 1910 vart det kunngjort at det skulle haldast ”almindelig Folketælling” for å få ei detaljert oversikt over Noregs befolkning natta mellom 1. og 2. desember 1910. På kvar bustad skulle alle personar til stades førast inn i teljingslista, med særskilt merknad om dei som var mellombels til stades (på besøk osv) på teljingstidspunktet. I tillegg skulle alle faste bebuarar som var fråverande (på reise, til sjøs osv) på teljingstidspunktet førast inn på lista. -

District 104C3.Pdf

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF FEBRUARY 2019 MEMBERSHI P CHANGES CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR TOTAL IDENT CLUB NAME DIST NBR COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 3277 019519 ÅSNES NORWAY 104C3 4 02-2019 27 0 0 0 0 0 27 3277 019521 BRUMUNDDAL NORWAY 104C3 4 02-2019 41 1 1 0 -7 -5 36 3277 019523 EIDSKOG NORWAY 104C3 4 02-2019 45 0 0 0 0 0 45 3277 019524 ELVERUM NORWAY 104C3 4 11-2018 35 2 0 0 -1 1 36 3277 019525 NORD-FRON NORWAY 104C3 4 02-2019 25 2 0 0 -1 1 26 3277 019526 GJØVIK NORWAY 104C3 4 02-2019 27 3 0 0 -2 1 28 3277 019527 GRAN NORWAY 104C3 4 09-2018 10 0 0 0 -1 -1 9 3277 019528 GRUE NORWAY 104C3 4 02-2019 31 2 0 0 -3 -1 30 3277 019529 HAMAR NORWAY 104C3 4 01-2019 20 0 0 0 -5 -5 15 3277 019530 JEVNAKER NORWAY 104C3 4 02-2019 23 3 0 0 -1 2 25 3277 019531 KONGSVINGER NORWAY 104C3 4 02-2019 24 1 0 0 -3 -2 22 3277 019533 LILLEHAMMER NORWAY 104C3 4 02-2019 25 1 0 0 -3 -2 23 3277 019535 LUNNER NORWAY 104C3 4 10-2018 18 0 0 0 -1 -1 17 3277 019539 NORDRE LAND NORWAY 104C3 4 10-2018 25 0 0 0 -2 -2 23 3277 019540 ODAL NORWAY 104C3 4 02-2019 41 1 0 0 -1 0 41 3277 019543 OTTA NORWAY 104C3 4 11-2018 17 0 0 0 0 0 17 3277 019544 ØSTRE TOTEN NORWAY 104C3 4 02-2019 27 2 0 0 0 2 29 3277 019545 ØYER-TRETTEN NORWAY 104C3 4 02-2019 21 0 0 0 0 0 21 3277 019546 RENA NORWAY 104C3 4 11-2018 29 1 0 0 -1 0 29 3277 019547 RINGSAKER NORWAY 104C3 4 12-2018 36 3 0 0 -5 -2 34 3277 019549 STANGE NORWAY 104C3 4 02-2019 28 0 0 0 0 0 28 3277 019550 STOR-ELVDAL -

Stikka 1 2016

Stikka Layout: John HAMAR Y’S MEN’S CLUB Red.: Nils Kristian Nr. 1 2016 Årg. 45 FASTETIDA – EIN VIKTIG DEL AV KYRKJEÅRET F astetida er førebuing til påske. Den starter pasjonsgudstenester i fastetida. Det førde mel ikkje med Fastelavnssøndag, men med Oske- lom anna til at det her i landet blei bestemt at onsdag. Fastelavnssøndag eller søndag før fas- ein skulle preika over deler av lidingssoga kvar te skal førebu oss for fastetida, uten å føregri- onsdag i fastetida. Denne tradisjonen frå 1639 pa den. Dagen står på overgangen mellom fylgjer ein framleis i mange kyrkjer. Tekstane ”stall og krubbe” og ”kross og død”. om Jesu liding blei først brukt mest i Den stille veka, men etter kvart kom desse tekstane også Oskeonsdag har sin bakgrunn i den kyrkje- til å prega heile fastetida som tekstar for lege tradisjonen med å teikna ein kross med gudstenester på kvardagane. oske på panna til dei som gjorde bot som eit uttrykk for at ein nå Kampmotivet er gjekk inn i ei botstid. Dei som truleg det mest domine- gjorde bot, blei først reinsa for rande motivet i fasteti- oska då fastetida var slutt. Då den. Eller kanskje vi hel- blei tekne opp i igjen i det fulle ler skulle tala om kamp fellesskapet i kyrkjelyden. og siger. Jesus er den som både har kjempa Det at Oskeonsdag fekk ei og sigra for oss, Hebr. 2 særskilt tyding, har samanheng v.18. Kamp- og si- med måten å rekna fastetida på. gersmotivet pregar Ganske tidleg i Oldkyrkja tok dei mange av tekstane vi til med å praktisera ei 40 dagars møter i denne tida av fastetid. -

Og Servicesenter, H

1. Vang speidergruppe 3. Eidsvoll speidergruppe 4H Hedmark Askjumlia velforening Balke Barnegospel Balke bo- og servicesenter, Hagegruppe Balke Pensjonistlag Barnas kulturdag på Stenberg Bilitt Vel Støttegruppe Biri IL Biri Seniordans Blomhaugskole FAU Borglund Vel Brystkreftforeningen Gjøvik-Toten BURG Oppland Bygdetunets Venner Bøn og Omegn Vel Bøverbru Hestesportsklubb Bøverbru idrettslag Bøverbru Vel Bøverbru/Eina Skolekorps CK Toten-tråkk Dal Idrettslag Dance4fun Dokken Velforening Eidsvold Turn Håndball Eidsvold Turnforening Fotball Eidsvold Værk Musikkorps Eidsvoll 1814´s Eidsvoll Basketball klubb Eidsvoll Speidergruppe Eidsvoll Svømmeklubb Eidsvold Værks Skiklub Eina Bygdekvinnelag Eina Dagsenter Eina Sanitetsforening Eina Sportsklubb Eina Ungdomsklubb Eina Vel Epilepsiforeningen i Hedmark og Oppland Feiring TeknoLab Feiringregjeringa Finnkollen Idrettslag Fjellvolls venner Forening til fremme for klassisk ballett i Gjøvik Foreningen Mot Kreft Fotballaget Fart Fredheim skolekorps Funkis IL Hedmark Furnes Bo-og aktivitetssenter, Venneforeningen Furua 4H Gartnerløkka Vel Gjøvik brettklubb Gjøvik Handicapidrettslag Gjøvik Innebandyklubb Gjøvik Jeger og Fiskerforening Gjøvik og Toten astronomiske forening Gjøvik og Toten flyklubb Gjøvik og Toten Sportsfiskeklubb Gjøvik Quiltelag Gjøvik Røde Kors Omsorg, avd. Barnehjelpen Gjøvik Skiklubb Skiskyting Gjøvik skiklubb, alpingruppa Grande Drilltropp GTL Rcklubben HalloVenn Eidsvoll Hamar Badmintonklubb Hamar Barne og Ungdomskor - Filiokus Hamar Frivilligsentral Hamar idrettslag - kunstløpgruppa -

Norske Mesterskap

TYNSET IF – Norske Mesterskap NM-resultater Pl- Pl- Pl- Chps Year Venue Name Club Res-1 Pl-1 Res-2 Pl-2 Res-3 3 Res-4 4 Res-5 5 Res-6 Pl-6 Res-7 Pl-7 JNMa 1967 Brandbu R Liv Wenche Telneset Tynset IF 51,1 4 1.47,8 3 2.53,2 5 162,73 3 JNMa 1967 Brandbu R Marit Bjørnsmoen Tynset IF 53,2 8 1.52,0 8 3.04,8 10 170,8 9 JNMa 1967 Narvik S Willy Olsen Tynset IF 43,6 11 4.42,6 2 2.17,5 5 8.23,9 1 186,92 2 JNMa 1968 Drammen M Willy Olsen Tynset IF 44,4 9 4.40,5 1 2.16,9 1 8.11,1 1 185,89 1 NMa 1969 Lillehammer S Willy Olsen Tynset IF 43,9 19 7.53,3 7 2.11,5 8 16.21,6 9 184,14 10 NMa 1970 Skien H Willy Olsen Tynset IF 43,26 13 7.51,4 8 2.12,9 9 16.34,2D LM-G-15 1971 Notodden S Bjørn Eidsvåg Tynset IF 46,2 7 2.28,6 8 95,73 6 NMa 1971 Moss M Willy Olsen Tynset IF 42,8 14 7.34,6 2 2.10,9 5 16.20,5 4 180,92 6 LM-G-12 1972 Lillestrøm S Bengt Grinden Tynset IF 52,4 14 LM-G-14 1972 Dokka S Jon Magne Vingelsgaard Tynset IF 57,2f 38 1.41,1 26 107,75 38 LM-G-16 1972 Dokka S Bjørn Eidsvåg Tynset IF 46 5 5.14,6 12 98,43 11 LM-J- 1972 Lillestrøm S Kari Lyngbakken Tynset IF 48,1 11 LM-J-1210/11 1972 Lillestrøm S Anne Bjørnsmoen Tynset IF 58,2 12 LM-J-14 1972 Dokka S Aud Johanne Mælen Tynset IF 53,1 8 1.52,5 6 109,35 7 NMa 1972 Tønsberg S Willy Olsen Tynset IF 42,47 13 7.36,88 1 2.12,01 10 16.07,07 4 180,52 4 LM-G-15 1973 Oppdal Jon Magne Vingelsgaard Tynset IF 45,3 15 2.28,0 16 94,63 13 LM-J-12 1973 Hønefoss S Kari Lyngbakken Tynset IF 57,1 11 LM-J-13 1973 Hønefoss S Anne Bjørnsmoen Tynset IF 55,3 8 LM-J-15 1973 Hønefoss S Aud Johanne Mælen Tynset IF 52,7 5 1.51,0 -

THE ROHNE FAMILY by Robert A. Bjerke 21 January 2013 M Henrik

THE ROHNE FAMILY by Robert A. Bjerke 21 January 2013 m Henrik Henriksen Spetalen Spetalen 1742 1745 d: 23 Octobr [1740] Troeloved ungekarl Hendrich Hendrichsøn Spetalen og Pigen Berthe Hendrichsdaatter, Cautionister Halvor Halvorsen Hæsnæs og Lars Knudsæn Hæsnæs; Copul: d: 29de Decembr 1740 (Stange m) Berthe Henriksdatter ?m 29 Sept 1753 Maria Johansdatter Children: 2 i Kari bp 1742; d: 7 Octobr [1742] Døbt Hendrich Hendrichsøn og Berthe Hendrichsdaater Spetalens ægte Daatter kaldet Kari Fadd: Gulbrand Larsøn Grøtholm, Erich Larsøn Voldene, Anne Nielsdaatter Grøtholm, Ingebor Engelbretsdaater Spetalen, og Kirsti Erichsdaatter Voldene; mother churched 9 Dec ii Henrich bp 1745; 13 June 1745 D;bt Henrich Henrichsen, og Berthe Henrichsd: Spitalen D:b: Nom: Hnerich, Fad Embret Olsen SaxrudEj, Anders Nielsen Skougsrud, Johan Olsen Hvæensbrænd: Karen Halvorsd: ibdm, Marthe Assersd: Tylien; mother churched 18 July iii Ole bp 10 Dec 1747, Døbt Henrich Henrichsen og Berthe Henrichsd: Spitalen Db: Nom: Ole, Fad: Elen Remmen, Margrethe Svenskerud, Michel Berget, Ole Theregaard, Ole Hvitberg (Stange bp); introd 1748, Festo Circumcisionis Xti, introd: Berthe Henrichsdtr Spitalens Eye rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr CHILDREN OF HENRIK HENRIKSEN AND BERTHE HENRIKSDATTER: 2 bp k 2 Kari Henriksdatter bp 7 Oct 1742; conf 1760, Spetalen 1 01 bp k m bur 3 Henrik Henriksen bp 13 June 1745; conf 1763 d 17 April 1825, føderaad paa pladsen Hersjøen Hersjøen. Nyebygger med jord, Hersiøen, 1801 m 23 Oct 1778 01 bp k Anne -

Nr. 220 CONTRIBUTIONS to the GEOLOGY of the MJØSA DISTRICTS and the CLASSICAL SPARAGMITE AREA in SOUTHERN NORWAY

Nr. 220 CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE GEOLOGY OF THE MJØSA DISTRICTS AND THE CLASSICAL SPARAGMITE AREA IN SOUTHERN NORWAY By STEINAR SKJESETH sammendrag: Bidrag til geologien i Mjøstraktene med en kort foreløpig analyse av stratigrafi og tektonikk i det klassiske sparagmittområde WITH 65 TEXT-FIGURES AND 2 PLATES OSLO 1963 UNIVERSITETSFORLAGET NORGES GEOLOGISKE UNDERSØKELSE NR. 220 CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE GEOLOGY OF THE MJØSA DISTRICTS AND THE CLASSICAL SPARAGMITE AREA IN SOUTHERN NORWAY By STEINAR SKJESETH sammendrag: Bidrag til geologien i Mjøstraktene med en kort foreløpig analyse av stratigrafi og tektonikk i det klassiske sparagmittområde WITH 65 TEXT-FIGURES AND 2 PLATES OSLO 1963 UNIVERSITETSFORLAGET Jo, 54? (W Editor for the Publications of the Geological Survey of Norway: State Geologist Fredrik Hagemann A.W. BRØGGERS BOKTRYKKERI A/S - OSLO Contents. Abstract 5 Acknowledgements 7 Introduction 9 The geological setting of the Mjøsa Districts 12 Historical review 13 STRATIGRAPHY 17 The Sparagmite Group "Eocambrian" 17 Eocambrian rocks within the mapped area Description of localities 19 Autochthonous series 21 Allochthonous series 26 The stratigraphy of the Sparagmite Group Elstad Sparagmite 27 Brøttum Sparagmite 27 Brøttum Shale and Limestone 28 Biri Conglomerate 28 Biri Shale and Limestone 29 Moelv Sparagmite 30 Moelv Conglomerate (= tillite) 31 Ekre Shale 32 Mjøsa Quartz-sandstone formation Vardal Sparagmite and Ringsaker Quartzite 32 The Cambrian System Description of localties Autochthonous series 35 Allochthonous series 44 The Cambrian