••• Beginnings of a Folk Hero

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coaches Vs Cancer

YOUTH & HIGH SCHOOL TOOLKIT coachesvscancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Coaches vs. Cancer Council LON KRUGER, CHAIR MIKE KRZYZEWSKI University of Oklahoma Duke University MIKE ANDERSON DAVID LEVY University of Arkansas Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. WARNER BAXTER Ameren PHIL MARTELLI St. Joseph’s University JAY BILAS ESPN FRAN MCCAFFERY Come and Play for Us University of Iowa JIM BOEHEIM The American Cancer Society and the National Association of Syracuse University GREG MCDERMOTT Creighton University Basketball Coaches (NABC) have teamed up in the fight against cancer. GARY BOWNE Hickory Christian Academy REGGIE MINTON Each year, youth and high school teams across the country have done NABC TAD BOYLE their part to raise funds and awareness in these efforts. Once again, we University of Colorado GARRY MUNSON Whitney Capital Company, invite schools and leagues to unite with basketball coaches across the MIKE BREY LLC country this season to raise funds to beat cancer. Teams have already University of Notre Dame DAVE PILIPOVICH signed up to participate. JIM CALHOUN Air Force Academy University of Saint Joseph As a coach and leader in your community, we’re asking you to use MICHAEL PIZZO BOBBY CREMINS GCA Advisors, LLC your influence to promote cancer awareness and raise funds for the Retired Head Coach DAVE R OSE American Cancer Society. FRAN DUNPHY Brigham Young University Temple University BO RYAN Don’t sit on the bench. Join in to make a difference in the fight DONNIE EPPLEY Retired Head Coach against cancer. International Association of Approved Basketball BOB SANSONE Officials, Inc. iTrust Advisors LLC ERAN GANOT MIKE SHULT What is Coaches vs. -

North Carolina Basketball Former Head Coach Dean Smith

2001-2002 NORTH CAROLINA BASKETBALL FORMER HEAD COACH DEAN SMITH When ESPN’s award-winning Sports Century program in at least one of the two major polls four times (1982, selected the greatest coaches of the 20th Century, it came 1984, 1993 and 1994). to no surprise that Carolina basketball coach Dean Smith • Smith’s teams were also the dominant force in the was among the top seven of alltime. Smith joined other Atlantic Coast Conference. The Tar Heels under Smith had legends Red Auerbach, Bear Bryant, George Halas, Vince a record of 364-136 in ACC regular-season play, a winning Lombardi, John McGraw and John Wooden as the preem- percentage of .728. inent coaches in sports history. • The Tar Heels finished at least third in the ACC regu- Smith’s tenure as Carolina basketball coach from 1960- lar-season standings for 33 successive seasons. In that 97 is a record of remarkable consistency. In 36 seasons at span, Carolina finished first 17 times, second 11 times and UNC, Smith’s teams had a record of 879-254. His teams third five times. won more games than those of any other college coach in • In 36 years of ACC competition, Smith’s teams fin- history. ished in the conference’s upper division all but one time. However, that’s only the beginning of what his UNC That was in 1964, when UNC was fifth and had its only teams achieved. losing record in ACC regular-season play under Smith at • Under Smith, the Tar Heels won at least 20 games for 6-8. -

Schedule of Events 29 to Oct

Sept. Schedule of events 29 to Oct. 9 Homecoming 5K 9 a.m., Sept. 29 Traditions Plaza Wear your favorite black and gold athletic Oct. gear to get in the spirit for Mizzou Homecoming. 11 Homecoming Headquarters Homecoming Blood Drive 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., Traditions Plaza 11 a.m. to 7 p.m., Sept. 30 to Oct. 3, Hearnes Center Grab some Homecoming merchandise, participate in MU is home to the largest blood drive in the state of giveaways and pick up some free kettle corn courtesy of the Missouri, collecting more than 3,000 units Bates County Mizzou Club. of blood annually. Campus Decorations — 6-9:30 p.m., Greektown Talent Show Hit the streets of Greektown to check out what the paired fraternities and Oct. 7-9, 6:30-9 p.m. sororities curated based on this year’s Homecoming theme. Stay to watch the Check out 12-minute Homecoming-themed skit they perform in front of the decorations. skits, dancers and singers during the three-day run of the Homecom- Taste of Columbia — 6-9 p.m., Greektown ing talent show. Sample a variety of offerings from food trucks, including The Big Cheeze, Big Daddy’s BBQ and Dippin’ Dots. Spirit Rally — 8:30 p.m., Traditions Plaza Get those vocal cords ready to cheer with Truman the Tiger, Marching Mizzou and the Mizzou Spirit Squads the eve before the big game. Decorate the District — Begins today, downtown Columbia Wander endlessly through downtown and check out the storefront paint- Oct. ings and decorations. Each spirited design is curated by a participating MU organization. -

Vol. 33 Issue 1 November 2019

Vol. 33 November Issue 1 2019 Vol. 33 January Issue 2 2020 What’s Inside 3 Letter from the Editor 4 How Video Scouting Has Changed the Game 8 First Year Here? 9 Yes, Zone Offense Works vs Junk Defenses – Here’s How 11 Honoring a True Basketball Family 13 Coaching Milestone Submissions 14 Our Favorite Play of the Month 15 MBCA Membership - What It Means To You Letter From the Editor Welcome to the halfway point of the season! After spending time over the holiday break participating in a holiday tournament or having a break from games, many teams are gearing up for the second half of the basketball season. For most basketball coaches who also teach, the holiday break at school means spending more time with your teams rather than enjoying time off from teaching. Utilizing the extra time of your break can be key to having a very successful second half of the season. However, the first couple of weeks after the break can be tough on a team. These ‘dog days’ of the basketball season can bring a team’s excitement and enthusiasm to a grinding halt. As coaches, we have the best knowledge of our team’s make up. Sometimes holiday break time means players are having a lot of unstructured time away from your team. Sometimes the break means more rigorous time for your players because their families are traveling and visiting other family. Both factors, along with others, will affect individual player’s performances in practices as well as games. Be sure to evaluate and utilize your holiday break practice times and time off that you give your players. -

Osher Lifelong Learning Center Spring 2019 Course Catalog

A Learning Community of Adults Aged 50 + Spring 2019 Course Catalog Registration opens February 26, 2019 Courses begin March 11, 2019 See Potpourri-- of the Arts - P. 23 version “Storied” with Larry Brown- P. 19 Archive extension.missouri.edu Master Pollinator Steward - P. 13 A UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI EXTENSION PROGRAM 1 Stay Young. Stay Connected. Join Osher@Mizzou. IN THIS ISSUE 8 Course calendar 10 Courses 26 Special events 32 How to support Osher 36 Letter from Advisory Council OSHER@MIZZOU Chair 344 Hearnes Center Columbia, MO 65211 37 Enrollment form Phone: 39 Directions and parking 573-882-8189 Email: This program is brought to you by MU Extension and [email protected] the Bernard Osher Foundation. Website: osher.missouri.edu ABOUT MU EXTENSION Jennifer Erickson Using research-based knowledge, University of Senior Coordinator Missouri Extension engages people to help them understand change, solve problems and make Walker Perkins informed decisions. Educational Program Associate MU Extension makes university education and Osher@Mizzou Advisory Council information accessible to create Jack Wax, Chair Nan Wolf, Vice Chair • economic viability, Helen Washburn, Past Chair • empowered individuals, Sharon Kinden, Secretary • strong families and communities and Don Bay • healthy environments. Tom Bender John Blakemore MU Extension partners with the University of Missouri campuses, Lincoln University, the people of Karen Chandler Missouri through county extension councils, and the Barbara Churchill National Institute for Food and Agriculture -

THE NCAA NEWS STAFF Mark Occasion

Official Publication of the National Collegiate Athletic Association December 14, 1994, Volume 3 1, Number 45 Women’s coaches find plenty to like about ESPN deal By Laura E. Bollig “I’m very excited. I think this is a land- THE NCAA NEWS STAFF mark occasion. It is going to be a signifi- cant happening for women’s basketball,” What they really wanted was a day off. said Jody Conradt, head women’s basket- What Division I women’s basketball pro- ball coach and director of women’s athlet- grams got was this: ics at the University of Texas at Austin. “I n More than three times the exposure to think we are going to follow the same pat- which they are accustomed. tern the men’s championship did with the n Virtually no competition for air time visibility it was afforded by ESPN initially.” with the men. Ditto from University of Tennessee, n A long-term television home for their Knoxville, head coach Pat Summitt. championship. “I think that’s good news for women’s H And, the day off. basketball. I think we’re at a stage right Women’s basketball coaches are cele- now in our growth where television expo- brating the announcement December 7 by sure is very important to our future and to ESPN that it has purchased the television the growth of our game. To have that type rights to 19 NCAA championships, includ- of extensive exposure in the postseason is ing exclusive rights to all rounds of the certainly great for the women’s game.” Division I Women’s Basketball Cham- pionship. -

2019 Homecoming Rulebook.Pdf

2019 TRADITIONS RULEBOOK UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI HOMECOMING TRI-DIRECTORS 1 LEVELS OF INVOLVEMENT 2 SOCIAL MEDIA 3 IMPORTANT DATES 4 BLOOD DRIVE 5 CAMPUS DECORATIONS 12 OUTREACH 23 PARADE 25 SERVICE 30 SPECIAL EVENTS 34 TALENT 39 TRADITIONS 42 APPENDIX & FORMS 46 OVERALL POINT OVERVIEW 56 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE DIRECTOR’S LETTER The Homecoming Steering Committee and the Mizzou Alumni Association would like to thank you for your participation in Homecoming 2019. This year marks the 108th anniversary of Chester Brewer calling Tigers everywhere to “come home” to the University of Missouri, thus creating the very first Homecoming. Students, faculty, staff, alumni, and community members have been continuing the tradition ever since with a celebration of Mizzou and her impressive history of excellence. We celebrate with campus traditions old and new to showcase all facets of the university. Students and stories from every corner of campus come together to put on festivities that add to Mizzou’s rich history while collectively forging paths that will last for another 108 years. The Mizzou Alumni Association is proud to celebrate Homecoming with a wide variety of top-notch events that serve the community: we host the largest student-run blood drive in the nation; the Homecoming Food Drive benefits the Food Bank for Central and Northeast Missouri; Campus Decorations and the Homecoming Parade are unique experiences that provide creative entertainment for the entire Mizzou family. These and the numerous other events that spread the infectious Tiger spirit every Homecoming season would not be possible without the time and selfless devotion of our students. -

What's Inside 3 MBCA Board 4 Gary Filbert Obituary 7 This and That 9

What’s Inside 3 MBCA Board 4 Gary Filbert obituary 7 This and That 9 Philosophies on Success or How to Get Rich Telling Others to Buy My Book 11 Coaches vs Cancer/MBCA Partnership 12 Man Makes Plans 15 Q&A With the Difference‐Makers: Kevin McArthy (Gateway AAU) 17 Is It Worth It? 19 MBCA Spring Board Minutes 24 What is Well‐Coached? 31 The Coach’s Clipboard 34 2011 MBCA Major Award Winners 37 2011 MBCA All‐State Teams 47 2011 MBCA Academic All‐State Teams Stephanie Phillips Mother, Wife, Daughter, Friend, Teacher and Coach 1974‐2010 This season’s editions of the Hard Court Herald are dedicated to our late MBCA president. Stephanie was an inspiration to everyone who knew her. We were all touched by her graciousness, enthusiasm and passion for life. 2 3 Gary Filbert, basketball coach and pioneer of the Show-Me State Games, dies at age 81 By Joe Walljasper Courtesy of Columbia Daily Tribune Brian Filbert is an FBI agent, and for a short time he was stationed in Mid-Missouri. One day, he got a call about a bank robbery in Mexico, Mo., in which a bomb was allegedly planted in the bank. Filbert pulled into the parking lot, full of adrenaline, and hustled up to the highway patrolman and police officer at the scene. “I introduce myself,” he said, “and I got about halfway into it, and the police officer said, ‘Are you Gary Filbert’s son?’ “I said, ‘Well, yeah, I am, but there’s a bomb in the bank.’ ” That story sums up the impact and influence of Gary Filbert. -

Sports Daily

WWW.KANSASCITY.COM THE KANSAS CITY STAR® WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 29, 2007 D Sports Daily HALL OF FAME FUTURE DATES OCT. 10 Ribbon cutting and public ceremony OCT. 11-16 Special opening-week NATIONAL COLLEGIATE BASKETBALL HALL OF FAME activities OCT. 17 Normal operating hours begin: Wednesday - Saturday, 10am-6 pm Sunday 11 am - 6 pm NOV. 18 National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame induction ceremony A SNEAK PEEK NOV. 19-20 CBE Classic at Sprint Center “They’ll want to come here, and they might not want to leave.” The hall of fame is a companion of the Sprint Center, and the buildings share a common entrance off Grand Boulevard. Go to the right, and you head toward the 18,500-seat Sprint Center that will be home to this fall’s CBE Classic and the Big 12 men’s basketball tournament next March. Head left and enter the 41,500-square foot College Basketball Experience, which will open with a ribbon- cutting ceremony on Oct. 10, hold a special week of activities Oct. 11-16 and will run regular operating hours starting Oct. 17. A month later, the second hall of fame class, which includes former Missouri coach Norm Stewart, will be inducted. It’ll be part of the Gallery of Honor on the building’s first floor. Also on the ground floor: an ESPN television set where visitors can make their own calls of the game’s great moments, and an area called Mentor’s Circle, which allows visitors to log video tributes to coaches in any sport who have influenced their lives. -

MU-Map-0118-Booklet.Pdf (7.205Mb)

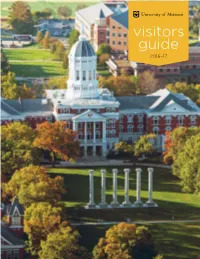

visitors guide 2016–17 EVEN WHEN THEY’RE AWAY, MAKE IT FEEL LIKE HOME WHEN YOU STAY! welcome Stoney Creek Hotel and Conference Center is the perfect place to stay when you come to visit the MU Campus. With lodge-like amenities and accommodations, you’ll experience a stay that will feel and look like home. Enjoy our beautifully designed guest rooms, complimentary to mizzou! wi-f and hot breakfast. We look forward to your stay at Stoney Creek Hotel & Conference Center! FOOD AND DRINK LOCAL STOPS table of contents 18 Touring campus works up 30 Just outside of campus, an appetite. there's still more to do and see in mid-Missouri. CAMPUS SIGHTS SHOPPING 2 Hit the highlights of Mizzou’s 24 Downtown CoMo is a great BUSINESS INDEX scenic campus. place to buy that perfect gift. 32 SPIRIT ENTERTAINMENT MIZZOU CONTACTS 12 Catch a game at Mizzou’s 27 Whether audio, visual or both, 33 Phone numbers and websites top-notch athletics facilities. Columbia’s venues are memorable. to answer all your Mizzou-related questions. CAMPUS MAP FESTIVALS Find your way around Come back and visit during 16 29 our main campus. one of Columbia’s signature festivals. The 2016–17 MU Visitors Guide is produced by Mizzou Creative for the Ofce of Visitor Relations, 104 Jesse Hall, 2601 S. Providence Rd. Columbia, MO | 573.442.6400 | StoneyCreekHotels.com Columbia, MO 65211, 800-856-2181. To view a digital version of this guide, visit missouri.edu/visitors. To advertise in next year’s edition, contact Scott Reeter, 573-882-7358, [email protected]. -

@Mizzoubaseball

@MIZZOUBASEBALL 1 @MIZZOUBASEBALL TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION Quick Facts _________________________ 2 Mizzou Communications Staff ____________ 3 Roster - Numerical ____________________ 4 Roster - Alphabetical __________________ 5 University/Athletics Leadership __________6-8 MEET THE TIGERS Connor Brumfield / Cameron Dulle _________ 9 Paul Gomez / Jordan Gubelman __________ 10 Zach Hanna / Spencer Juergens _________ 11 Tyler LaPlante / Trevor Mallett ___________ 12 Tony Ortiz / Jacob Cantleberry ___________ 13 Chris Cornelius / Austin James __________ 14 Art Joven / Jake Matheny ______________ 15 Kameron Misner / TJ Sikkema ___________ 16 Lukas Veinbergs / Peter Zimmerman ______ 17 Luke Anderson / Konnor Ash ____________ 18 Ian Bedell / Thomas Broyles ____________ 19 Trey Dillard / Chad McDaniel ____________ 20 Alex Peterson / Clayton Peterson _________ 21 Cameron Pferrer / Mark Vierling _________ 22 Seth Halvorsen / Josh Holt Jr. ____________ 23 Nick Lommen / Luke Mann _____________ 23 Tre Morris / Ty Olejnik _________________ 24 Trae Robertson / Tommy Springer ________ 24 Cameron Swanger / Nick Swanson _______ 25 COACHES & STAFF Steve Bieser _____________________ 26-27 Lance Rhodes / Fred Corral _____________ 28 Jake Epstein / Jae Fadde ______________ 29 Austin Tribby / Brett Peel ______________ 30 Support Staff _______________________ 31 2018 SEASON IN REVIEW Season Stats _______________________ 32 SEC Only Stats ______________________ 33 Results Summary ____________________ 34 Miscellaneous Stats __________________ 35 PROGRAM -

Coaches Vs. Cancer Announces 2019 Award

Coaches vs. Cancer Announces 2019 Award Youth Official Lou Levine honored for his impact on the fight against cancer Massachusetts youth basketball official Lou Levine has been honored with a Champion Award, a prestigious national honor from the Coaches vs. Cancer program. This is the first time an official has been selected to receive the award. The Champion Award honors individuals who have shown extraordinary leadership and commitment to the American Cancer Society's mission of saving lives, celebrating lives and fighting cancer from every angle. The awards were presented during Final Four Weekend in April at the Guardians of the Game Awards Show in Minneapolis. Since 2011, Lou Levine has raised approximately $600,000 for the American Cancer Society. He has donated more than 1,600 basketball game fees which total approximately $75,000. In additional to his personal fundraising, he has been instrumental in the growth of the campaign through his outreach to coach and sporting official associations throughout the Northeast. "The Champion Award is our opportunity to recognize true leaders in the fight against cancer," said Sharon Byers, chief development and marketing officer of the American Cancer Society. "Mr. Levine is an inspiration. His commitment and dedication is raising funds, awareness and rallying even more people to join our team and defeat cancer." Coaches vs. Cancer is a collaboration between the American Cancer Society and the National Association of Basketball Coaches (NABC) that empowers coaches, their teams, and communities to join in saving more lives. The program leverages the personal experiences, community leadership, and professional excellence of basketball coaches nationwide to increase cancer awareness and promote healthy living through year-round awareness efforts, fundraising activities, and advocacy programs.