RL Aug 2014 Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplementary Materials 1

Supplementary materials 1 Table S1 The characteristics of botanical preparations potentially containing alkenylbenzenes on the Chinese market. Botanical Pin Yin Name Form Ingredients Recommendation for daily intake (g) preparations (汉语) Plant food supplements (PFS) Si Ji Kang Mei Yang Xin Yuan -Rou Dou Kou xylooligosaccharide, isomalt, nutmeg (myristica PFS 1 Fu He Tang Pian tablet 4 tablets (1.4 g) fragrans), galangal, cinnamon, chicken gizzards (四季康美养心源-肉豆蔻复合糖片) Ai Si Meng Hui Xiang fennel seed, figs, prunes, dates, apples, St.Johns 2-4 tablets (2.8-5.6 g) PFS 2 Fu He Pian tablet Breed, jamaican ginger root (爱司盟茴香复合片) Zi Ran Mei Xiao Hui Xiaong Jiao Nang foeniculi powder, cinnamomi cortex, papaya PFS 3 capsule concentrated powder, green oat concentrated powder, 3 capsules (1.8 g) (自然美小茴香胶囊) brewer’s yeast, cabbage, monkey head mushroom An Mei Qi Hui Xiang Cao Ben Fu He Pian fennel seed, perilla seed, cassia seed, herbaceous PFS 4 tablet 1-2 tablets (1.4-2.8 g) (安美奇茴香草本复合片) complex papaya enzymes, bromelain enzymes, lactobacillus An Mei Qi Jiao Su Xian Wei Ying Yang Pian acidophilus, apple fiber, lemon plup fiber, fennel PFS 5 tablet seed, cascara sagrada, jamaican ginger root, herbal 2 tablets (2.7 g) (安美奇酵素纤维营养片) support complex (figs, prunes, dates, apples, St. Johns bread) Table S1 (continued) The characteristics of botanical preparations potentially containing alkenylbenzenes on the Chinese market. Pin Yin Name Botanical Form Ingredients Recommendation for daily intake (g) preparations (汉语) Gan Cao Pian glycyrrhiza uralensis, licorice -

Stars for Your Garden from Down Under

JANUARY / FEBRUARY 2003 Serving You Since 1955 981 Alden Lane, Livermore, CA www.aldenlane.com (925) 447-0280 Announcements Watch the Valley Gardener for great gardening tips with host Jacquie Williams-Courtright. Tune in 4 days a week on Cable Channel 30. Monday: 9 am & 3:30 pm, Friday: Stars For 3 p.m. and Saturday-Sunday: 7 am, 11 am & 2:30 pm. Your Garden Livermore-Amador Valley Garden From Down Under Club meets the first Tuesday of the month, join us on January 7th at 7 p.m. at Alisal School, 1454 Santa Rita By Lydia Roberts Rd, Pleasanton, Ca. For more No, Im sorry we havent got Nicole Kidman or Russell Crowe waiting to go information call Bev at 485-7812. This months speaker will be: Simone home with you, but we have got some beautiful floral stars that are center stage Martell, author of Expectant this month in the garden while our Californian talent is still preparing for their Gardener will talk about what we performance later in the season. can look forward to in our gardeners. The climate in much of Australia and New Zealand is Mediterranean, similar to On February 4th hear Judy Sandkuhle, Central California. It can be a Little cooler here in the winter but most of the plants owner of Sunset Color, talk about her suggested below are hardy to 20 degrees F. They are evergreen and flower from favorite plants and flowers. winter through spring bringing a welcome touch of color. Generally they are easy to care for. They need little to no fertilizer, especially do not use a high phosphorus fertilizer as this can kill them. -

October 2009 Volume 3, Page 1

by any other name the newsletter of the World Federation of RoseRose Societies’ Heritage Rose Group Contents A letter from the President Texas Teas David Ruston, Australia..............................................................................2 by Claude Graves, Texas, USA.......................................................22 Minutes of the Heritage Roses Committee Royal Roses Vancouver, 23 June 2009......................................................................3 by Sheenagh Harris, South Africa...............................................24 A rosarium for Serbia Roses on the move by Radoslav Petrovic´, Serbia.............................................................8 by Helga Brichet, Italy..............................................................................30 Roses and rose gardens of New Zealand Vacunae Rosae —portrait of a new rose garden by Doug Grant, New Zealand.............................................................10 by Gian Paolo Bonani, Italy.................................................................36 the making of Between the Rows The Canadian Hybrbridiser, Dr Felicitas Svejda by Joanne Knight, New Zealand...................................................12 by Dr Patrick White, Canada...........................................................44 Roses from cuttings by Malcolm Manners, USA.................................................................14 Pruning roses — breaking all the rules by Gregg Lowery, USA............................................................................16 -

December 2020 WFRS World Rose News 1

December 2020 WFRS World Rose News 1 EDITOR’S MESSAGE Table of Contents Cover Page (Composite Designed by John Mata) ······· 1 Happy holidays! Our blessings are that we made it to the end Editor’s Message ··························································· 2 of the year 2020, a year that never was. Hopefully all of our Table of Contents ·························································· 2 friends and family made it through to see the next year and what it may hold. President’s Message ····················································· 3 Our cover for this issue by John Mata is of ‘Neil Diamond’, a Executve Director’s Message ······································· 4 very fragrant striped Hybrid Tea from Weeks. Rose News ····································································· 5 In this end of the year issue we feature more “Secret WFRS Publicatons For Sale ··········································· 6 Gardens” from all over the world, top award winners from the Internatonal Rose Trials, and an update on the World Top Rose Trial Winners ················································· 7 Rose Conventon 2022. Secret Garden: Bennet’s Court, England ··················· 10 Secret Garden: Miss Kity’s Garden, US ······················ 13 Enjoy! Six Countries - Six Great Gardens ································ 16 Rose News From Chile ················································ 20 Steve Jones, Fiddletown, CA, United States 2022 World Rose Conventon Update ························ 23 WFRS Ofce Bearers ··················································· -

NLI Recommended Plant List for the Mountains

NLI Recommended Plant List for the Mountains Notable Features Requirement Exposure Native Hardiness USDA Max. Mature Height Max. Mature Width Very Wet Very Dry Drained Moist &Well Occasionally Dry Botanical Name Common Name Recommended Cultivars Zones Tree Deciduous Large (Height: 40'+) Acer rubrum red maple 'October Glory'/ 'Red Sunset' fall color Shade/sun x 2-9 75' 45' x x x fast growing, mulit-stemmed, papery peeling Betula nigra river birch 'Heritage® 'Cully'/ 'Dura Heat'/ 'Summer Cascade' bark, play props Shade/part sun x 4-8 70' 60' x x x Celtis occidentalis hackberry tough, drought tolerant, graceful form Full sun x 2-9 60' 60' x x x Fagus grandifolia american beech smooth textured bark, play props Shade/part sun x 3-8 75' 60' x x Fraxinus americana white ash fall color Full sun/part shade x 3-9 80' 60' x x x Ginkgo biloba ginkgo; maidenhair tree 'Autumn Gold'/ 'The President' yellow fall color Full sun 3-9 70' 40' x x good dappled shade, fall color, quick growing, Gleditsia triacanthos var. inermis thornless honey locust Shademaster®/ Skyline® salt tolerant, tolerant of acid, alkaline, wind. Full sun/part shade x 3-8 75' 50' x x Liriodendron tulipifera tulip poplar fall color, quick growth rate, play props, Full sun x 4-9 90' 50' x Platanus x acerifolia sycamore, planetree 'Bloodgood' play props, peeling bark Full sun x 4-9 90' 70' x x x Quercus palustris pin oak play props, good fall color, wet tolerant Full sun x 4-8 80' 50' x x x Tilia cordata Little leaf Linden, Basswood 'Greenspire' Full sun/part shade 3-7 60' 40' x x Ulmus -

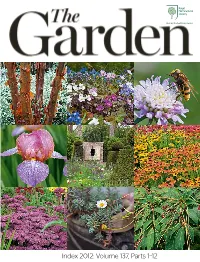

RHS the Garden 2012 Index Volume 137, Parts 1-12

Index 2012: Volume 137, Parts 112 Index 2012 The The The The The The GardenJanuary 2012 | www.rhs.org.uk | £4.25 GardenFebruary 2012 | www.rhs.org.uk | £4.25 GardenMarch 2012 | www.rhs.org.uk | £4.25 GardenApril 2012 | www.rhs.org.uk | £4.25 GardenMay 2012 | www.rhs.org.uk | £4.25 GardenJune 2012 | www.rhs.org.uk | £4.25 RHS TRIAL: LIVING Succeed with SIMPLE WINTER GARDENS GROWING BUSY LIZZIE RHS GUIDANCE Helleborus niger PLANTING IDEAS WHICH LOBELIA Why your DOWNY FOR GARDENING taken from the GARDEN GROW THE BEST TO CHOOSE On home garden is vital MILDEW WITHOUT A Winter Walk at ORCHIDS SHALLOTS for wildlife How to spot it Anglesey Abbey and what to HOSEPIPE Vegetables to Radishes to grow instead get growing ground pep up this Growing chard this month rough the seasons summer's and leaf beet at Tom Stuart-Smith's salads private garden 19522012: GROW YOUR OWN CELEBRATING Small vegetables OUR ROYAL for limited spaces PATRON SOLOMON’S SEALS: SHADE LOVERS TO Iris for Welcome Dahlias in containers CHERISH wınter to the headline for fi ne summer displays Enjoy a SUCCEED WITH The HIPPEASTRUM Heavenly summer colour How to succeed ALL IN THE MIX snowdrop with auriculas 25 best Witch hazels for seasonal scent Ensuring a successful magnolias of roses peat-free start for your PLANTS ON CANVAS: REDUCING PEAT USE IN GARDENING seeds and cuttings season CELEBRATING BOTANICAL ART STRAWBERRY GROWING DIVIDING PERENNIALS bearded iris PLUS YORKSHIRE NURSERY VISIT WITH ROY LANCASTER May12 Cover.indd 1 05/04/2012 11:31 Jan12 Cover.indd 1 01/12/2011 10:03 Feb12 Cover.indd 1 05/01/2012 15:43 Mar12 Cover.indd 1 08/02/2012 16:17 Apr12 Cover.indd 1 08/03/2012 16:08 Jun12 OFC.indd 1 14/05/2012 15:46 1 January 2012 2 February 2012 3 March 2012 4 April 2012 5 May 2012 6 June 2012 Numbers in bold before ‘Moonshine’ 9: 55 gardens, by David inaequalis) 10: 25, 25 gracile ‘Chelsea Girl’ 7: the page number(s) sibirica subsp. -

Her Royal Highness Crown Princess Mary Is Patron of the 18Th World Rose Convention

Volume 29 • Number 2 • May, 2018 Her Royal Highness Crown Princess Mary is Patron of the 18th World Rose Convention May, 2018 1 Contents Editorial 2 President’s Message 3 All about the President 4 Immediate PP Message 6 New Executive Director 8 WFRS World Rose Convention – Lyon 9 Pre-convention Tours Provence 9 The Alps 13 Convention Lecture Programme Post Convention Tours Diary of Events WFRS Executive Committee Standing Com. Chairmen Member Societies Associate Members and Breeders’ Club Friends of the Federation I am gragteful EDITORIAL CONTENT This is the nineteenth issue of WRN since I was invited to be Editor Editorial 2 towards the end of 2012. It has been an enlightening 6 years, President’s Message 3 sometimes positive and sometimes not. The Editor is vulnerable to criticism, but the many emails of gratitude and encouragement World Rose Convention made it all so worthwhile. In particular I enjoyed the contact with The Story of Poulsen Roses 4 rosarians throughout the world. I tried to include as many WFRS Std. Com. Reports different people as possible and from a variety of member Awards 7 countries of the world and I hope they have looked upon it as an Breeders’ Club 7 Classification & Registration 8 honour and not a chore. Cons. & Heritage Roses 8 Convention Liaison 9 Seven pages are devoted to the important reports from the Honours 10 International Judges 11 Chairmen of Standing Committees. Here we have good coverage International Rose Trials 11 of the governance of the WFRS – what goes on behind the scenes Promotions 12 keeping the wheels going round. -

An Earthwise Guide for Central Texas

Native and Adapted green.org Landscape Plants City of Austin grow City of Find your perfect plant with our online seach tool! an earthwise guide for Central Texas Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service A&M Texas Native and Adapted Landscapean earthwise Plants guide for Central Texas This guide was developed to help you in your efforts to protect and preserve our water resources. Index Key Trees ............................................................ 7 Native to: Evergreen or Deciduous: E - Edwards Plateau, Rocky, Western Zone: shallow, E – Evergreen Small Trees / Large Shrubs ........................ 9 limestone or caliche soil (generally on the west SE – Semi-evergreen side of Austin) D – Deciduous Shrubs (including roses) ............................ 15 B - Blackland Prairie, Eastern Zone: Deeper, dark, clay soils (generally on the east side of Austin) Water: Refers to the plant’s water needs during the growing Perennials .................................................. 25 B/E - Native to both Edwards Plateau and season after they are established. The majority of plants Blackland Prairie require more water while becoming established. For Austin’s current water restrictions, variances and other T - Native to Texas (not a part of Edwards Plateau or Yuccas/Agaves/Succulents/Cacti/Sotols .. 39 irrigation information visit www.WaterWiseAustin.org Blackland Prairie) VL – Very Low (Water occasionally, if no significant rain Hybrid plant with native Texas parentage Ornamental & Prairie Grasses ................... 41 X - for 30 days) For additional native plant information, visit the plant L – Low (Water thoroughly every 3-4 weeks if no Vines .......................................................... 43 section of the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower website at significant rainfall) www.wildflower.org M – Medium (Water thoroughly every 2-3 weeks if Groundcovers ........................................... -

Rose List 2016 Save 20% Off the Retail Price by Ordering Before December 1, 2015 Discounts Apply to Prepaid Orders ONLY

Rose List 2016 Save 20% off the retail price by ordering before December 1, 2015 Discounts apply to prepaid orders ONLY. Pre-ordered roses are supplied bareroot — all others are potted. Bring on the roses! Here is our new Rose List for 2016 which includes many classics as well as 20 new varieties. Here's hoping there is one that you will love. We receive our roses in early January and plant them into biodegradable pulp pots, so they can be planted throughout the season. If you're planting roses for the first time, pick up our flyer for instructions on planting roses in pulp pots. Popular varieties sell out quickly, so for the best selection come in early! As always, it is our intention to supply all roses listed, however, due to circumstances beyond our control some varieties may not be available. N Denotes new introductions for 2016 and varieties new at Orchard Smokin' Hot Fragrance is denoted as: f Light Fragrance ff Moderate Fragrance fff Strong Fragrance Modern Bush Roses $34.99 R1157 Elle Shell Pink / Ivory fff Hybrid Tea R1 Abbaye de Cluny Apricot Yellow fff Romantica® R1276 Eternal Flame Soft Yellow fff Hybrid Tea R1156 About Face Golden w/ Bronze Reverse f Grandiflora R1302 Falling In Love Pink w/Cream Reverse fff Hybrid Tea R1440 Adobe Sunrise Salmon Orange Floribunda R1387 Firefighter Dusty Velvet Red fff Hybrid Tea R1412 Always And Forever Bright Ruby Red Hybrid Tea R230 First Prize Pink Hues f Hybrid Tea R30 Angel Face Lavender fff Floribunda R244 Fragrant Cloud Coral / Red fff Hybrid Tea R1626 Anna's Promise Orange/ Apricot -

The Friends of Vintage Roses 2021 Rose Sale Shop Online—Pickup in Sebastopol

THE FRIENDS OF VINTAGE ROSES 2021 ROSE SALE SHOP ONLINE—PICKUP IN SEBASTOPOL Welcome to our 2021 virtual rose sale! Thank you Friends at 3003 Pleasant Hill Rd, Sebastopol, for supporting this non-profit plant preservation CA 95472. Later dates for pickup will be effort as we strive to assure the survival of a great announced on our Rose Sales page. collection of historic roses. We know you will WE CANNOT SHIP PLANTS. recognize the rarity of what we offer this year, in- PRICES cluding many very old varieties that have not pre- viously been available to purchase in North Amer- $20 each for all band roses, $25 for all one-gallon ica. We urge you to give a home to some of these roses and $30 for all 5-gallon plants. beauties and to become a curator of old roses. We currently plan a late summer sale of addition- TERMS OF OUR SALE Comice de Tarn-et-Garonne (Bourbon) al roses in July, and a third sale in September or October. — Submit orders by email to: from Gregg. Once you have received a con- [email protected] firmation, you may make payment by check THE LISTS — Your order should contain the following: to The Friends of Vintage Roses and sent to A simple list for ease of scanning is also posted on our Sebastopol address below, or on our Rose our Rose Sales page next to this PDF link. 1. Your name and preferred email address. Sales Page online, by clicking on the top most We encourage you to go to Help Me Find Roses payment button, labeled “Buy Now”. -

Rome Hotel Eden

ROME HOTEL EDEN Two day itinerary: Romance Italians are considered some of the most romantic people in the world, so where better to celebrate your love than in the Italian capital of Rome? From charming gardens and intimate restaurants to jewellery shopping and jaw-dropping views, there are plenty of opportunities to create lasting memories in the Eternal City. Spend a romantic weekend away in Rome with the help of this two-day itinerary. Day One Start the day with a 20-minute drive to The Orange Garden. THE ORANGE GARDEN Via di Santa Sabina, 00153 Rome While its name suggests that the highlight of The Orange Garden (Giardino degli Aranci or Parco Savello) is its orchard of fruit trees, its views are, in fact, its most captivating attraction. The pocket- sized garden directly overlooks St Peter’s Basilica and its terrace offers unbelievably beautiful views of Rome. Visit with your partner in the morning, when the sun casts an enchanting glow over the city. Take a short five-minute walk to the next garden on the itinerary. ROME ROSE GARDEN T: 006 574 6810 | Via di Valle Murcia 6, 00153 Rome Nothing says romance like a walk through a blossoming rose garden. Rome Rose Garden (Roseto Comunale) at the foot of Aventino Hill is one of the city’s most charming green spaces. Open from May to October each year, the garden is filled with over 1,000 different varieties of botanical roses from all over the world, with some dating back to Roman times. Then, take a 25-minute drive to Keats-Shelley House. -

World Rose News

VOLUME 21 : FEBRUARY 2010 World Rose News NEWSLETTER of the WORLD FEDERATION of ROSE SOCIETIES EDITOR Richard Walsh, 6 Timor Close, Ashtonfield NSW, Australia 2323 Phone: +61 249 332 304 or +61 409 446 256 Email: <[email protected]> WFRS was founded in 1968 and is registered in the United Kingdom as a company limited by guarantee and as a charity under the number 1063582. The objectiv es of the Society, as stated in the constitution, are: • To encourage and facilitate the interchange of information and knowledge of the rose between national rose societies. • To co-ordinate the holding of international conventions and exhibitions. • To encourage and, where appropriate, sponsor research into problems concerning the rose. • To establish common standards for judging new rose seedlings. • To establish a uniform system of rose classification. • To grant international honours and/or awards. • To encourage and advance international co-operation on all other matters concerning the rose. DISCLAIMERS While the advice and information in this journal is believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication, neither the authors, editor nor the WFRS can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The WFRS makes no warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein. Editor’s Comments This is our second all electronic edition of World Rose News . This edition contains reports from Regional Vice-Presidents and also from some of our Standing Committees, Associate Members, newer members, gardens of note, awards to distinguished rosarians, a tribute to Frank Benardella, some articles about roses and dates of up-coming events in the rose world…in short, a celebration of roses and rosarians.