Lincoln P. Bloomfield Revision I December 21, 1959 C/ 59-27

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Gaming World Issue

I - Vol. 3 No. 4 Jul.-Aug. - 1983 FEATURES SUSPENDED 10 The Cryogenic Nightmare David P. Stone M.U.L.E. 12 One of Electronic Arts' New Releases Edward Curtis BATTLE FOR NORMANDY 14 Strategy and Tactics Jay Selover SCORPION'S TALE 16 Adventure Game Hints and Tips Scorpia COSMIC BALANCE CONTEST WINNER 17 Results of the Ship Design Contest KNIGHTS OF THE DESERT 18 Review Gleason & Curtis GALACTIC ADVENTURES 20 Review & Hints David Long COMPUTER GOLF! 29 Four Games Reviewed Stanley Greenlaw BOMB ALLEY 35 Review Richard Charles Karr THE COMMODORE KEY 42 A New Column Wilson & Curtis Departments Inside the Industry 4 Hobby and Industry News 5 Taking a Peek 6 Tele-Gaming 22 Real World Gaming 24 Atari Arena 28 Name of the Game 38 Silicon Cerebrum 39 The Learning Game 41 Micro-Reviews 43 Reader Input Device 51 Game Ratings 52 Game Playing Aids from Computer Gaming World COSMIC BALANCE SHIPYARD DISK Contains over 20 ships that competed in the CGW COSMIC BALANCE SHIP DESIGN CONTEST. Included are Avenger, the tournament winner; Blaze, Mongoose, and MKVP6, the judge's ships. These ships are ideal for the gamer who cannot find enough competition or wants to study the ship designs of other gamers around the country. SSI's The Cosmic Balance is required to use the shipyard disk. PLEASE SPECIFY APPLE OR ATARI VERSION WHEN ORDERING. $15.00 ROBOTWAR TOURNAMENT DISK CGW's Robotwar Diskette contains the source code for the entrants to the Second Annual CGW Robotwar Tournament (with the exception of NordenB) including the winner, DRAGON. -

Debtbook Diplomacy China’S Strategic Leveraging of Its Newfound Economic Influence and the Consequences for U.S

POLICY ANALYSIS EXERCISE Debtbook Diplomacy China’s Strategic Leveraging of its Newfound Economic Influence and the Consequences for U.S. Foreign Policy Sam Parker Master in Public Policy Candidate, Harvard Kennedy School Gabrielle Chefitz Master in Public Policy Candidate, Harvard Kennedy School PAPER MAY 2018 Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. This paper was completed as a Harvard Kennedy School Policy Analysis Exercise, a yearlong project for second-year Master in Public Policy candidates to work with real-world clients in crafting and presenting timely policy recommendations. Design & layout by Andrew Facini Cover photo: Container ships at Yangshan port, Shanghai, March 29, 2018. (AP) Copyright 2018, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America POLICY ANALYSIS EXERCISE Debtbook Diplomacy China’s Strategic Leveraging of its Newfound Economic Influence and the Consequences for U.S. Foreign Policy Sam Parker Master in Public Policy Candidate, Harvard Kennedy School Gabrielle Chefitz Master in Public Policy Candidate, Harvard Kennedy School PAPER MARCH 2018 About the Authors Sam Parker is a Master in Public Policy candidate at Harvard Kennedy School. Sam previously served as the Special Assistant to the Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs at the Department of Homeland Security. As an academic fellow at U.S. Pacific Command, he wrote a report on anticipating and countering Chinese efforts to displace U.S. -

Twixt Ocean and Pines : the Seaside Resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 5-1996 Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Souther, Jonathan Mark, "Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930" (1996). Master's Theses. Paper 1037. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWIXT OCEAN AND PINES: THE SEASIDE RESORT AT VIRGINIA BEACH, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Master of Arts University of Richmond, 1996 Robert C. Kenzer, Thesis Director This thesis descnbes the first fifty years of the creation of Virginia Beach as a seaside resort. It demonstrates the importance of railroads in promoting the resort and suggests that Virginia Beach followed a similar developmental pattern to that of other ocean resorts, particularly those ofthe famous New Jersey shore. Virginia Beach, plagued by infrastructure deficiencies and overshadowed by nearby Ocean View, did not stabilize until its promoters shifted their attention from wealthy northerners to Tidewater area residents. After experiencing difficulties exacerbated by the Panic of 1893, the burning of its premier hotel in 1907, and the hesitation bred by the Spanish American War and World War I, Virginia Beach enjoyed robust growth during the 1920s. While Virginia Beach is often perceived as a post- World War II community, this thesis argues that its prewar foundation was critical to its subsequent rise to become the largest city in Virginia. -

Lootboxes" in Digital Games - a Gamble with Consumers in Need of Regulation? an Evaluation Based on Learnings from Japan

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Koeder, Marco Josef; Tanaka, Ema; Mitomo, Hitoshi Conference Paper "Lootboxes" in digital games - A gamble with consumers in need of regulation? An evaluation based on learnings from Japan 22nd Biennial Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): "Beyond the Boundaries: Challenges for Business, Policy and Society", Seoul, Korea, 24th-27th June, 2018 Provided in Cooperation with: International Telecommunications Society (ITS) Suggested Citation: Koeder, Marco Josef; Tanaka, Ema; Mitomo, Hitoshi (2018) : "Lootboxes" in digital games - A gamble with consumers in need of regulation? An evaluation based on learnings from Japan, 22nd Biennial Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): "Beyond the Boundaries: Challenges for Business, Policy and Society", Seoul, Korea, 24th-27th June, 2018, International Telecommunications Society (ITS), Calgary This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/190385 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Acquire: Fun-And-Fortune Game for 2 Players. 1 Hour 15 Min Game Time

List of 2-player games available to borrow from Bowdoin Board Game Club: Acquire: fun-and-fortune game for 2 players. 1 hour 15 min game time. Beyond Baker Street: A card-based Sherlock Holmes mystery game. 30 min game time. Carcassonne the Castle: the two-player version of the classic. 30-45 min game time. Chess: two players battle to death. Game time varies. Clans: A board game set in late pre-history. Easy rules, challenging game. 30 min game time. Cosmic Encounter: the sci fi game for everyone. Very cool board. “A teeth-gritting, mind-croggling, marvelously demanding exercise in ‘what if’.” – Harlan Ellison Coup: Only one can survive. Secret identities, deduction, deception. 15 game time. El Grande Big Box – (includes 6 expansions): Spain in the late middle ages, win with cunning and guile. 60 min game time. Evolution: A dynamic game of survival. 60 min game time. FLUXX: The card game with ever-changing rules. 5-30 min game time. Forbidden Island: Adventure if you DARE! 30 min game time. Gobblet: The fun strategy board game for 2. 10-20 min game time. Grifters: are you devious enough to rob the corporations blink, swindle your opponent and pull off daring heists? 30 game time. Hanabi: A cooperative firework launching game for 2. 30 min game time. Inis: immerse yourself in celtic legends. A truly beautiful game. 60 min game time. Jaipur: A subtle trading game for 2 players. 30 min game time. King of New York: You are a giant monster and you want to become King of New York. -

Axis and Allies 1914 Optional Rule: Research and Development

AXIS AND ALLIES 1914 OPTIONAL RULE: RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT Using this rule, you may attempt to develop improved military technology. If you decide to use Research & Development, it becomes the new phase 1 of the turn sequence, bumping the other phases up a number. Germany begins with Advanced Rail Network and Increased Mobilization. Austria-Hungary begins with Advanced Rail Network. Russia begins with Advanced Rail Network and Increased Mobilization. Britain begins with War Bonds. France begins with Advanced Rail Network and Increased Mobilization. Research and Development Sequence 1. Buy research dice 2. Roll research dice 3. Roll breakthrough die 4. Mark developments Step 1: Buy Research Dice Each research die costs 3 IPCs to develop a technology on the tier 1 chart and 6 IPCs to develop a technology on the tier 2 chart. Once a nation has acquired FOUR tier 1 technologies, the cost per die for tier 1 and tier 2 technologies becomes 3 IPCs for that nation. Buy as many as you wish, including none. Every turn, Germany, France, and Britain receives one free 3 IPC valued research die, which represents automatic ongoing war research. Step 2: Roll Research Dice Roll each of your purchased research dice. You must roll all tier 1 research dice before rolling any tier 2 research dice. Success: If you roll at least one “6”, you have successfully made a technological breakthrough. Continue to step 3. Failure: If you don’t roll a “6”, your research has failed. Step 3: Roll Breakthrough Die If your research was successful, reference the appropriate tier(s) of the research chart (below) and roll a single die on each tier to see which technological advance you get. -

Russia Selective Capitalism and Kleptocracy

21st Century Authoritarians Freedom House Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Radio Free Asia JUNE 2009 FFH_UD7.inddH_UD7.indd iiiiii 55/22/09/22/09 111:221:22 AAMM RUSSIA SELECTIVE CAPITALISM AND KLEPTOCRACY Daniel Kimmage The Kremlin deploys the conceptual vocabulary of the new Russia—national renewal, anti-Western xenophobia, sovereign democracy—through a sophis- ticated domestic communications strategy that marshals both the traditional state resources and much-expanded control over virtually all mainstream mass media. This one-two punch, coming amid a period of rising prosperity, has had a signifi cant impact on popular opinion, and the Kremlin’s message has resonated with its intended recipients. introduction When Russian tanks halted their advance a few kilometers from Tbilisi in August 2008, with the Georgian army in full fl ight and Georgia’s allies in Europe and the United States reduced to fulmination, the global consensus on the meaning of the invasion was swift and bracing: Russia was back, a force to be reckoned with, and intent on reclaiming its lost share of import and infl uence among nations. This consensus is as wrongheaded and simplistic as the previous incarnations of con- ventional wisdom it has replaced: fi rst, that Russia was engaged in a rollicking, rollercoaster transition from communist torpor to liberal democracy and a free-market economy, and then, when that fi ne vision foundered in fi nancial crisis and sundry misadventures toward the end of the 1990s, that Russia had become mired in some intermediary phase of its supposed transition and might soon slink off history’s grand stage altogether. -

The AVALON HILL

N... "'0'".. ... '" 2 *The AVALON HILL ic': ~iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiAiiiiiiiViiiiiiiaiiiiiiilOiiiiiiiniiiiiiiHiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiliiiiiiilPiiiiiiihiiiiiiiiiiiiiiilOiiiiiiiSiiiiiiiPiiiiiiihYiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiPiiiiiiiariiiiiiitiiiiiii9iiiiiiioiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii~ GENERAL Has it really been ten years? As I ponder bring grognard on any readership. You've suffered long The Game Players Magazine ing this column to life for the 60th time it seems enough at my hands. The opportunity for your hard to believe, but calendars don't lie. Vol. 9, No. magazine to take on fresh ideas under new leader The Avalon Hill GENERAL is dediCated to the presenta" 1 was my maiden voyage as editor of THE ship is long overdue. While I am genuinely proud of lion of authoritative articles on the strategy; tactics, and GENERAL, and now a scant ten years later I must the format we have developed for THE GENERAL variation of Avalon Hill wargames. Historical articles are Jncludedonly insomuch as they provide useful background relinquish the helm to another as time marches on. during the past decade, perhaps greater things can information On current Avalon Hill titles. The GENERALis For this, dear reader, is my last issue as your trusty be accomplished from the vantage point of a fresh published by the Avalon Hill Game CompanY solelv fot the (or is that crusty) old editor. perspective. I have been advised from time to time aficionado,rn~the cultural edification of the serious game that mine is a rather opinionated and dry style much hopes ofimpfoving the game owner's proficiency of play and providing services not otherwise available to the Avalon Hill too grating on the nerves of those with dissimilar game buff .. Avalon Hill is a division of Monarch Avalon Yes, I've finally been kicked upstairs into the tastes. -

A Runequest 6Th Edition Rules Supplement X

A RuneQuest 6th Edition Rules Supplement X CREDITS Research, Rules, Mechanics and Lead Writing: Pete Nash Additional Material: Lawrence Whitaker Editing and Layout: Lawrence Whitaker DISCLAIMER This unofficial article uses some material from the Wookieepedia Wiki, an invaluable website for all Star Wars related information. Many thanks to the creators and their efforts. Star Wars and other associated names are the sole and exclusive property of Lucasfilm Limited. Their inclusion within this article is under Fair Use purposes only to enable fans to create their own games based in the Star Wars universe. We heartily suggest that those interested in running a full and professional Star Wars game (rather than this feeble freebie hack) should look at the recently released and Edge of Empire produced by Fantasy Flight Games. INTRODUCTION Most owners of RuneQuest 6th Edition will probably have purchased it with the intent to run games set in traditional fantasy settings. As it stands the book can pretty much cover anything from historical Neolithic hunter-gatherers to Arabian Nights Sword & Sorcery. Yet the underly- ing mechanics of RuneQuest are flexible enough to represent any genre. Of course a Game Master needs to invest a little more work if planning to run a game in an atypical setting. Whilst the Design Mechanism intends to publish some more modern setting books in the future, this article is the first of an informal series to show just how easy it is to make your own conversions (commonly known as ‘hacks’) to play in the more infamous Sci-Fi and Fantasy worlds. To start the ball rolling we’ll show how you can use RQ6 to run a Star Wars based game, which is about as far removed from S&S as can be imagined. -

Russian Strategic Intentions

APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE Russian Strategic Intentions A Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) White Paper May 2019 Contributing Authors: Dr. John Arquilla (Naval Postgraduate School), Ms. Anna Borshchevskaya (The Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Dr. Belinda Bragg (NSI, Inc.), Mr. Pavel Devyatkin (The Arctic Institute), MAJ Adam Dyet (U.S. Army, J5-Policy USCENTCOM), Dr. R. Evan Ellis (U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute), Mr. Daniel J. Flynn (Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI)), Dr. Daniel Goure (Lexington Institute), Ms. Abigail C. Kamp (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START)), Dr. Roger Kangas (National Defense University), Dr. Mark N. Katz (George Mason University, Schar School of Policy and Government), Dr. Barnett S. Koven (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START)), Dr. Jeremy W. Lamoreaux (Brigham Young University- Idaho), Dr. Marlene Laruelle (George Washington University), Dr. Christopher Marsh (Special Operations Research Association), Dr. Robert Person (United States Military Academy, West Point), Mr. Roman “Comrade” Pyatkov (HAF/A3K CHECKMATE), Dr. John Schindler (The Locarno Group), Ms. Malin Severin (UK Ministry of Defence Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre (DCDC)), Dr. Thomas Sherlock (United States Military Academy, West Point), Dr. Joseph Siegle (Africa Center for Strategic Studies, National Defense University), Dr. Robert Spalding III (U.S. Air Force), Dr. Richard Weitz (Center for Political-Military Analysis at the Hudson Institute), Mr. Jason Werchan (USEUCOM Strategy Division & Russia Strategic Initiative (RSI)) Prefaces Provided By: RDML Jeffrey J. Czerewko (Joint Staff, J39), Mr. Jason Werchan (USEUCOM Strategy Division & Russia Strategic Initiative (RSI)) Editor: Ms. -

Kremlin Allies' Expanding Control of Runet Provokes Only Limited Opposition

UNCLASSIFIED//FOUO 28 February 2010 OpenSourceCenter Media Aid Kremlin Allies' Expanding Control of Runet Provokes Only Limited Opposition Pro-Kremlin oligarchs have gradually acquired significant stakes in the most popular websites in Russia, apparently seeking profitable investments, while augmenting other government moves to establish control over the Russian Internet. While specific population segments are intensely alarmed about Internet censorship and take steps to expose or thwart government efforts, the majority of the public is unconcerned about freedom of the press or Internet and is unlikely to oppose censorship of the Internet. With the government closely controlling TV and much of the press, the Internet has been the main venue for expression of opposition views, and social networking sites, which have become extremely popular, have developed outside government control. Television remains the leading and most popular source of information in Russia and the Russian Government maintains tight control of it for this reason, with the most popular channels being owned by the state or progovernment oligarchs. However, social networking sites have grown dramatically in popularity in recent years and are now the most popular websites in the Russian Internet. Sites such as VKontakte, a Facebook clone, Odnoklassniki, a Classmates.com clone, and LiveJournal, a blogging platform, now attract a monthly audience of many millions of users each. The Kremlin has taken notice of the increasing significance of the Internet and social media sites in particular and has begun enacting laws and policies aimed at giving it greater control. Kremlin-friendly oligarchs, who may also be motivated by the profitability of these sites, have also begun investing heavily into the top social networking and Internet outlets, potentially creating a situation similar to that of the national television networks. -

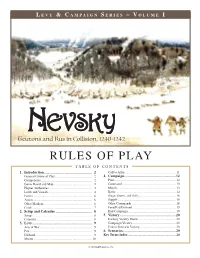

Rules of Play T a B L E O F C O N T E N T S 1

Nevsky 1 L EVY & C AMPAIGN S ERIE S – V O L UME I Teutons and Rus in Collision, 1240-1242 RULES OF PLAY T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S 1. Introduction ..................................................... 2 Call to Arms ............................................................. 11 General Course of Play............................................. 2 4. Campaign ......................................................... 12 Components .............................................................. 2 Plan ........................................................................... 12 Game Board and Map............................................... 2 Command ................................................................. 13 Higher Authorities .................................................... 3 March........................................................................ 13 Lords and Vassals ..................................................... 4 Battle ........................................................................ 14 Forces ....................................................................... 6 Siege, Storm, and Sally ............................................ 16 Assets ....................................................................... 6 Supply ....................................................................... 18 Other Markers........................................................... 6 Other Commands ...................................................... 18 Cards ........................................................................