Archino, Critical Deployment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gelett Burgess - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Gelett Burgess - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Gelett Burgess(30 January 1866 – 18 September 1951) Frank Gelett Burgess was an artist, art critic, poet, author and humorist. An important figure in the San Francisco Bay Area literary renaissance of the 1890s, particularly through his iconoclastic little magazine, The Lark, he is best known as a writer of nonsense verse. He was the author of the popular Goops books, and he invented the blurb. <b>Early life</b> Born in Boston, Burgess was "raised among staid, conservative New England gentry". He attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology graduating with a B.S. in 1887. After graduation, Burgess fled conservative Boston for the livelier bohemia of San Francisco, where he took a job working as a draftsman for the Southern Pacific Railroad. In 1891, he was hired by the University of California at Berkeley as an instructor of topographical drawing. <b>Cogswell fountain incident</b> In 1894, Burgess lost his job at Berkeley as a result of his involvement in an attack on one of San Francisco's three Cogswell fountains, free water fountains named after the pro-temperance advocate Henry Cogswell who had donated them to the city in 1883. As the San Francisco Call noted a year before the incident, Cogswell's message, combined with his enormous image, irritated many: <i>It is supposed to convey a lesson on temperance, as the doctor stands proudly on the pedestal, with his whiskers flung to the rippling breezes. In his right hand he holds a temperance pledge rolled up like a sausage, and the other used to contain a goblet overflowing with heaven's own nectar. -

NEO-Orientalisms UGLY WOMEN and the PARISIAN

NEO-ORIENTALISMs UGLY WOMEN AND THE PARISIAN AVANT-GARDE, 1905 - 1908 By ELIZABETH GAIL KIRK B.F.A., University of Manitoba, 1982 B.A., University of Manitoba, 1983 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Fine Arts) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA . October 1988 <£> Elizabeth Gail Kirk, 1988 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Fine Arts The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date October, 1988 DE-6(3/81) ABSTRACT The Neo-Orientalism of Matisse's The Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra), and Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, both of 1907, exists in the similarity of the extreme distortion of the female form and defines the different meanings attached to these "ugly" women relative to distinctive notions of erotic and exotic imagery. To understand Neo-Orientalism, that is, 19th century Orientalist concepts which were filtered through Primitivism in the 20th century, the racial, sexual and class antagonisms of the period, which not only influenced attitudes towards erotic and exotic imagery, but also defined and categorized humanity, must be considered in their historical context. -

Florine Stettheimer's Family Portrait II: Cathedrals of the Elite Family

motive / 1 Florine Stettheimer’s Family Portrait II: Cathedrals of the Elite Family Cara Zampino Excerpt 1 Florine Stettheimer’s 1915 painting Family Portrait I marks the beginning of her series of portraits featuring family members and friends. On the whole, the scene portrayed is quite mundane. In the painting, the Stettheimer family, which consisted of Florine, Carrie, Ettie, and their mother, is depicted gathered around a small table. Two of the sisters engage in discussion, another fixes a small bouquet of flowers, and the mother reads a book. The three sisters sport similar dresses, all of which are simple and lack ornate details, and the mother dons a plain black outfit.1 Over a decade after her initial portrayal of her family in Family Portrait I, Florine Stettheimer recreated and updated the image of the Stettheimers through her 1933 painting Family Portrait II, which depicts the same figures gathered in an extremely unusual setting that is a far cry from the quotidian table scene of the first portrait. As a whole, the women are living in a world with various fantastical elements. A bouquet of three flowers that are larger than the ladies themselves surround them; a striking red and yellow carpet borders a body of water; and various New York landmarks, such as the Chrysler Building and Statue of Liberty, float in the sky. Yet, the family unit is also divided—they gaze in separate directions, wear distinct, expensive-looking clothing, and hold objects that appear to be representative of their different personalities, including a painter’s palette, a book, and a cigarette. -

Representations of the Female Nude by American

© COPYRIGHT by Amanda Summerlin 2017 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BARING THEMSELVES: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE FEMALE NUDE BY AMERICAN WOMEN ARTISTS, 1880-1930 BY Amanda Summerlin ABSTRACT In the late nineteenth century, increasing numbers of women artists began pursuing careers in the fine arts in the United States. However, restricted access to institutions and existing tracks of professional development often left them unable to acquire the skills and experience necessary to be fully competitive in the art world. Gendered expectations of social behavior further restricted the subjects they could portray. Existing scholarship has not adequately addressed how women artists navigated the growing importance of the female nude as subject matter throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I will show how some women artists, working before 1900, used traditional representations of the figure to demonstrate their skill and assert their professional statuses. I will then highlight how artists Anne Brigman’s and Marguerite Zorach’s used modernist portrayals the female nude in nature to affirm their professional identities and express their individual conceptions of the modern woman. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I could not have completed this body of work without the guidance, support and expertise of many individuals and organizations. First, I would like to thank the art historians whose enlightening scholarship sparked my interest in this topic and provided an indispensable foundation of knowledge upon which to begin my investigation. I am indebted to Kirsten Swinth's research on the professionalization of American women artists around the turn of the century and to Roberta K. Tarbell and Cynthia Fowler for sharing important biographical information and ideas about the art of Marguerite Zorach. -

An Artist of the American Renaissance : the Letters of Kenyon Cox, 1883-1919 PDF

An Artist of the American Renaissance : The Letters of Kenyon Cox, 1883-1919 PDF Author: H. Wayne Morgan Pages: 197 pages ISBN: 9780873385176 Kenyon Cox was born in Warren, Ohio, in 1856 to a nationally prominent family. He studied as an adolescent at the McMicken Art School in Cincinnati and later at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. From 1877 to 1882, he was enrolled at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, and then in 1883 he moved to New York city, where he earned his living as an illustrator for magazines and books and showed easel works in exhibitions. He eventually became a leading painter in the classical style-particularly of murals in state capitols, courthouses, and other major buildings-and one of the most important traditionalist art critics in the United States.An Artist of the American Renaissance is a collection of Cox's private correspondence from his years in New York City and the companion work to editor H. Wayne Morgan's An American Art Student in Paris: The Letters of Kenyon Cox, 1877-1882 (Kent State University Press, 1986). These frank, engaging, and sometimes naive and whimsical letters show Cox's personal development as his career progressed. They offer valuable comments on the inner workings of the American art scene and describe how the artists around Cox lived and earned incomes. Travel, courtship of the student who became his wife, teaching, politics of art associations, the process of painting murals, the controversy surrounding the depiction of the nude, promotion of the new American art of his day, and his support of a modified classical ideal against the modernism that triumphed after the 1913 Armory Show are among the subjects he touched upon.Cox's letters are little known and have never before been published. -

Suzanne Preston Blier Picasso’S Demoiselles

Picasso ’s Demoiselles The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece Suzanne PreSton Blier Picasso’s Demoiselles Blier_6pp.indd 1 9/23/19 1:41 PM The UnTold origins of a Modern MasTerpiece Picasso’s Demoiselles sU zanne p res T on Blie r Blier_6pp.indd 2 9/23/19 1:41 PM Picasso’s Demoiselles Duke University Press Durham and London 2019 Blier_6pp.indd 3 9/23/19 1:41 PM © 2019 Suzanne Preston Blier All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Cover designed by Drew Sisk. Text designed by Mindy Basinger Hill. Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro and The Sans byBW&A Books Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Blier, Suzanne Preston, author. Title: Picasso’s Demoiselles, the untold origins of a modern masterpiece / Suzanne Preston Blier. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018047262 (print) LCCN 2019005715 (ebook) ISBN 9781478002048 (ebook) ISBN 9781478000051 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 9781478000198 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Picasso, Pablo, 1881–1973. Demoiselles d’Avignon. | Picasso, Pablo, 1881–1973—Criticism and interpretation. | Women in art. | Prostitution in art. | Cubism—France. Classification: LCC ND553.P5 (ebook) | LCC ND553.P5 A635 2019 (print) | DDC 759.4—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018047262 Cover art: (top to bottom): Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, detail, March 26, 1907. Museum of Modern Art, New York (Online Picasso Project) opp.07:001 | Anonymous artist, Adouma mask (Gabon), detail, before 1820. Musée du quai Branly, Paris. Photograph by S. P. -

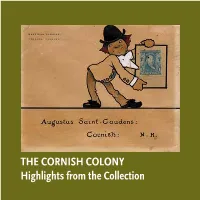

The Cornish Colony Highlights from the Collection the Cornish Colony Highlights from the Collection

THE CORNISH COLONY Highlights from the Collection THE CORNISH COLONY Highlights from the Collection The Cornish Colony, located in the area of Cornish, New The Cornish Colony did not arise all of apiece. No one sat down at Hampshire, is many things. It is the name of a group of artists, a table and drew up plans for it. The Colony was organic in nature, writers, garden designers, politicians, musicians and performers the individual members just happened to share a certain mind- who gathered along the Connecticut River in the southwest set about American culture and life. The lifestyle that developed corner of New Hampshire to live and work near the great from about 1883 until somewhere between the two World Wars, American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The Colony is also changed as the membership in the group changed, but retained a place – it is the houses and landscapes designed in a specific an overriding aura of cohesiveness that only broke down when the Italianate style by architect Charles Platt and others. It is also an country’s wrenching experience of the Great Depression and the ideal: the Cornish Colony developed as a kind of classical utopia, two World Wars altered American life for ever. at least of the mind, which sought to preserve the tradition of the —Henry Duffy, PhD, Curator Academic dream in the New World. THE COLLECTION Little is known about the art collection formed by Augustus Time has not been kind to the collection at Aspet. Studio fires Saint-Gaudens during his lifetime. From inventory lists and in 1904 and 1944 destroyed the contents of the Paris and New correspondence we know that he had a painting by his wife’s York houses in storage. -

Les Demoiselles D'avignon (1). Exposition, Paris, Musée Picasso, 26 Janvier-18 Avril 1988

3 Paris, Musée Picasso 26 janvier - 18 avril 1988 Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux Paris 1988 Cette exposition a été organisée par la Réunion des musées nationaux et le Musée Picasso. Elle a bénéficié du soutien d'==^=~ = L'exposition sera présentée également à Barcelone, Museu Picasso, du 10 mai au 14 juillet 1988. Couverture : Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, 1907 (détail), New York, The Museum of Modern Art, acquis grâce au legs Lillie P. Bliss, 1939. e The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1988. ISBN 2-7118-2.160-9 (édition complète) ISBN 2-7118-2.176-5 (volume 1) @ Spadem, Paris, 1988. e Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris, 1988. Commissaire Hélène Seckel conservateur au Musée Picasso 1 Citée dans le livre de François Chapon, Mystère et splendeurs de Jacques Doucet, Paris, J.-C. Lattès, 1984, p. 278. Ceci à propos du manuscrit de Charmes que possédait Jacques Doucet, dont il demande à Valéry quelques lignes propres à jeter sur cette oeuvre « des clartés authentiques ». 2 Christian Zervos, « Conversation avec Picasso », Cahiers d'art, tiré à part du vol. X, n° 7-10, 1936, p. 42. 3 Archives du MoMA, Alfred Barr Papers. 4 Bibliothèque littéraire Jacques Doucet. « Le goût que nous avons pour les choses de l'esprit s'accompagne presque néces- sairement d'une curiosité passionnée des circonstances de leur formation. Plus nous chérissons quelque créature de l'art, plus nous désirons d'en connaître les ori- gines, les prémisses, et le berceau qui, malheureusement, n'est pas toujours un bocage du Paradis Terrestre ». -

Rose Standish Nichols and the Cornish Art Colony

Life at Mastlands: Rose Standish Nichols and the Cornish Art Colony Maggie Dimock 2014 Julie Linsdell and Georgia Linsdell Enders Research Intern Introduction This paper summarizes research conducted in the summer of 2014 in pursuit of information relating to the Nichols family’s life at Mastlands, their country home in Cornish, New Hampshire. This project was conceived with the aim of establishing a clearer picture of Rose Standish Nichols’s attachment to the Cornish Art Colony and providing insight into Rose’s development as a garden architect, designer, writer, and authority on garden design. The primary sources consulted consisted predominantly of correspondence, diaries, and other personal ephemera in several archival collections in Boston and New Hampshire, including the Nichols Family Papers at the Nichols House Museum, the Rose Standish Nichols Papers at the Houghton Library at Harvard University, the Papers of the Nichols-Shurtleff Family at the Schlesinger Library at the Radcliffe Institute, and the Papers of Augustus Saint Gaudens, the Papers of Maxfield Parrish, and collections relating to several other Cornish Colony artists at the Rauner Special Collections Library at Dartmouth College. After examining large quantities of letters and diaries, a complex portrait of Rose Nichols’s development emerges. These first-hand accounts reveal a woman who, at an early age, was intensely drawn to the artistic society of the Cornish Colony and modeled herself as one of its artists. Benefitting from the influence of her famous uncle Augustus Saint Gaudens, Rose was given opportunities to study and mingle with some of the leading artistic and architectural luminaries of her day in Cornish, Boston, New York, and Europe. -

Misfired Canon (A Review of the New Moma)

NEW YORK NEW MOMA WINTER 2020 WINTER / OPENED OCTOBER 21 news ART At the new MoMA, Faith Ringgold’s 1967 painting American People Series No. 20: Die (below) is paired with Picasso’s famed 1907 canvas Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. Misfred Canon A feminist curator fnds the rehang seriously lacking. BY MAURA REILLY URING THE 1990S, WHILE and, ultimately, Jackson Pollock. According by my boss from cheekily offering a tour of pursuing my graduate art history to Barr, “modern art” was a synchronic, “women artists in the collection” at a time degree at New York University, I linear flow of “isms” in which one (hetero- when there were only eight on view. worked in the Education Depart- sexual, white) male “genius” from Europe or By the turn of the 21st century, the rele- Dment of the Museum of Modern Art, where the U.S. influenced another who inevitably vance of mainstream modernism was being I led gallery tours of the museum’s perma- trumped or subverted his previous master, challenged, and anti-chronology became nent collection for the general public and thereby producing an avant-garde progres- all the rage. The Brooklyn Museum, the VIPs. At that time, the permanent exhibition sion. Barr’s story was so ingrained in the High Museum of Art, and the Denver Art galleries, representing art produced from institution that it was never questioned as Museum all rehung their collections accord- 1880 to the mid-1960s, were arranged to problematic. The fact that very few women, ing to subject instead of chronology, and a tell the “story” of modern art as conceived artists of color, and those not from Europe much-anticipated inaugural exhibition at by founding director Alfred H. -

Completed Dissertations

Completed Dissertations Yale University Department of the History of Art 1942 TO PRESENT 190 York Street PO Box 208272 New Haven, CT 06520 203-432-2668 Completed Dissertations YALE UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF THE HISTORY OF ART Completed Dissertations from 1942 - Present Listed are the completed dissertations by Yale History of Art graduate students from 1942 to present day. 1942 Hamilton, George Heard, “Delacroix and the Orient” Studies in the Iconography of the Romantic Experience” 1945 Frisch, Teresa Grace, “A Study in Nomadic Art with Emphasis on Early Sythian Conventions and Motifs” 1948 Hamilton, Florence Wiggin, “The Early Work of Paul Gaugin: From Impressionism to Synthetism” Smith, Helen Wade, “Ptolemaic Heads: An Investigation of Sculptural Style” 1949 Averill, Louise Hunt, “John Vanderlyn: American Painter 1775-1852” Danes, Gibson A., “William Morris Hunt: A Biographical and Critical Study of 1824-1879” Newman, Jr., Richard King, “Yankee Gothic: Medieval Architectural Forms in Protestant Church Building of 19th Century New England” Peirson, Jr., William Harvey, “Industrial Architecture in the Berkshires” Scully, Jr., Vincent J., “The Cottage Style: An Organic Development in Later 19th Century Wooden Domestic Architecture in the Eastern United States” 1951 Davidson, J. LeRoy, “The Lotus Sutra in Chinese Art to the Year One Thousand” 1953 Branner, Robert J., “The Construction of the Chevet of Bourges Cathedral and its Place in Gothic Architecture” FORM013 8-JUN-2021 Page 1 Completed Dissertations Spencer, John R., “Leon Battista Alberti on Painting” Wu, Nelson Ikon, “T’and Ch’i-ch’ang and His Landscape Paintings” 1955 Spievogel, Rosalind Brueck, “Wari: A Study in Tiahuanaco Style” 1956 Donnelly, Marian Card, “New England Meeting Houses in the 17th Century” Hadzi, Martha Leeb, “The Portraiture of Gallienus (A.D. -

The Other Side of American Exceptionalism: Thematic And

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1999 The other side of American exceptionalism: thematic and stylistic affinities in the paintings of the Ashcan School and in Mark Twain's Captain Stormfield's Visit to Heaven Ng Lee Chua Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Chua, Ng Lee, "The other side of American exceptionalism: thematic and stylistic affinities in the paintings of the Ashcan School and in Mark Twain's Captain Stormfield's Visit to Heaven" (1999). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16258. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16258 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The other side of American ExceptionaIism: Thematic and stylistic affinities in the paintings of the Ashcan School and in Mark Twain's Captain Stormfield's Visit to Heaven by Ng Lee Chua A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Literature) Major Professor: Constance J. Post Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1999 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is