Symptoms, Causes, and Coping Strategies for Performance Anxiety in Singers: a Synthesis of Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reducing Public Speaking Anxiety with Behavior Modification Techniques Among School Students: a Study

The International Journal of Indian Psychology ISSN 2348-5396 (e) | ISSN: 2349-3429 (p) Volume 5, Issue 1, DIP: 18.01.011/20170501 DOI: 10.25215/0501.011 http://www.ijip.in | October-December, 2017 Original Research Paper Reducing Public Speaking Anxiety with Behavior Modification Techniques among School Students: A Study Sunil K Jangir1*, Reddy B. Govinda2 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to investigate whether the behavior modification techniques helps the students to reduce public speaking anxiety and enhancement in the Self-esteem. The fifty Students were selected purposively for the study on the basis of their Subjective Unit of Distress Scale (SUDS) developed by Wolpe (1990). The questionnaire Personal Report of Public Speaking Anxiety - 34 developed by McCroskey (2013) was adapted to determine the level of public speaking anxiety while holding the speech. Another instrument was Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965) in order to measures global self-worth by measuring both positive and negative feelings about the self, before and after intervention. This is the study of fifty student of IX standard, Kendriya Vidyalaya. The students were assessed pre intervention and intervened with Behaviour Modification techniques for the period of Six weeks. The interventions used for the study were: (i) Public speaking with similar problem in the presence of similar group (Ganesan, 2008) (ii) Establishing dialogues with audience in a graded manner in groups one to twenty members (Ganesan, 2009) (iii) Purposeful faltering, while speaking to overcome fear of failure while speaking (Ganesan, 2010) and (iv) Perform voice and breathing exercises (Ganesan, 2012). The student’s SUDS, PRPSA-34 and RSE were reassessed after the period of six weeks interventions phase of how to manage their distress and results of the study indicate that the students experienced significantly less anxiety. -

Treating Anxiety with Either Beta Blockers Or Antiemetic

Mental Health in Family Medicine 2015; 11:89-99 2015 Mental Health and Family Medicine Ltd Review Article TreatingResearch Article Anxiety with either Beta Blockers or AntiemeticOpen Access Antimuscarinic Drugs: A Review Thomas P. Dooley, Ph.D. TPD LLC, 7100 Cabin Lane, Pinson, Alabama 35126, USA; Tel: 205-222-6145; E-mail: [email protected] AbSTRACT Beta adrenergic receptor antagonists and antiemetic scopolamine) or over-the-counter (e.g., meclizine) for the muscarinic receptor antagonists are useful for mental health treatment of non-cardiovascular symptoms that manifest in in primary care and family medicine settings, as they provide anxiety disorders. Antiemetic agents inhibit nausea, vomiting, favorable risk/benefit profiles, and especially so relative to sweating, and in some instances other psychic (CNS) symptoms. benzodiazepines. Beta blockers (e.g., propranolol) prescribed The symptoms affected by antimuscarinic agents represent the off-label have been known for decades to provide some, “inverse” of the symptoms of acute anxiety affected by beta albeit limited, anxiolytic benefit for patients affected by blockers. Thus, anxiety disorders can be treated by alternative social anxiety disorder (social phobia), including performance biochemical pathways, as well as by affecting alternative anxiety. Blockage of adrenaline’s binding to cardiovascular symptoms thereof. The results of human clinical studies are beta adrenergic receptors inhibits tachycardia, reduces blood summarized for both classes of anxiolytic agents that display pressure, and thus diminishes palpitations in acute anxiety complementary pharmacologic approaches to a diverse array and panic. However, beta blockers are not effective against of symptoms. the psychic (CNS) symptoms, such as anxiousness, fear, and MeSH Headings/Keywords: Anxiety, Panic, Anxiolytic, avoidance. -

The Management of Performance Anxiety with Beta-Adrenergic Blocking Agents

Jefferson Journal of Psychiatry Volume 9 Issue 2 Article 5 June 1991 The Management of Performance Anxiety with Beta-Adrenergic Blocking Agents James A. Bourgeois, M.D. Wright State University School of Medicine, Dayton, Ohio Follow this and additional works at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/jeffjpsychiatry Part of the Psychiatry Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Recommended Citation Bourgeois, M.D., James A. (1991) "The Management of Performance Anxiety with Beta-Adrenergic Blocking Agents," Jefferson Journal of Psychiatry: Vol. 9 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.29046/JJP.009.2.002 Available at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/jeffjpsychiatry/vol9/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jefferson Digital Commons. The Jefferson Digital Commons is a service of Thomas Jefferson University's Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL). The Commons is a showcase for Jefferson books and journals, peer-reviewed scholarly publications, unique historical collections from the University archives, and teaching tools. The Jefferson Digital Commons allows researchers and interested readers anywhere in the world to learn about and keep up to date with Jefferson scholarship. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Jefferson Journal of Psychiatry by an authorized administrator of the Jefferson Digital Commons. For more information, please contact: [email protected]. The Management of Performance Anxiety with Beta-Adrenergic Blocking Agents James A. Bourgeois, M.D. Abstract Performance anxiety consists qf several symptoms experienced in the context qf public performance and is classified in DSM-III-R under social phobia.Performance anxiety must be distinguished from panic disorder, generalized social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder. -

Current P SYCHIATRY

Current p SYCHIATRY Performance anxiety: How to ease stage fright Artists may need customized medication and behavioral therapy © Doug Plummer / Photonica he violin is slippery in my grasp. I hear the T thud of my foot tapping, but the tempo feels Victoria C. Kelly, MD wrong. I’m aware of my chest pounding, a lump in Clinical house staff, department of psychiatry my throat, and heat rising from my face. Everyone is Radu V. Saveanu, MD watching me, waiting for me to make a mistake. Chairman, department of psychiatry Why can’t I stop my hand from trembling? I can only watch as the bow jumps noisily across the Ohio State University Medical Center, Columbus strings. I should have practiced more. My mind goes blank, and I miss the page turn. Silence. I blink, and the lights blind me as the applause comes, thankfully, and I exhale and run off the stage as the curtain closes. Well-known performing artists—Sir Laurence Olivier, Kim Basinger, Peter O’Toole, Richard VOL. 4, NO. 6 / JUNE 2005 25 Stage fright NORMAL VS. ABNORMAL FEAR Figure Performance anxiety is characterized by Performance anxiety features persisting, distressful apprehension overlap with other anxieties about—or actual impairment of—per- formance skills to a degree unwarrant- ed by the individual’s aptitude, training, Performance 1 anxiety and preparation. Not all performance anxiety qualifies as a mental disorder; for example, though 85% of the popula- tion experiences discomfort about public speaking,4 this anxiety does not impair most people’s ability to function. Specific Social phobia anxiety Mild to moderate anxiety is nor- mal and motivating in performances.5 However, anxiety’s effect on perfor- mance does not follow a bell-shaped curve, wherein moderate anxiety pro- Panic and other motes optimal performance.6 Instead, anxiety disorders a catastrophic model is more accurate: increasing anxiety is helpful until a certain threshold is reached, then Performance anxiety is not easy to categorize. -

MANAGING PERFORMANCE ANXIETY Celia Slattery

MANAGING PERFORMANCE ANXIETY Celia Slattery Almost everyone who sings in public has experienced stage fright at one time or another. This can range from a little fluttery feeling in your stomach before you go on stage, to the kind of severe panic attacks that hamper one’s career and make it almost impossible to perform, such as that famously experienced by Barbra Streisand. What is performance anxiety - or stage fright - how does it manifest itself, and what can you do about it? When we are nervous about performing in public, we react with the fight-or-flight response, and our bodies flood with a rush of adrenaline. This reaction was very handy when we were cavemen reacting to a dangerous situation, such as a dinosaur about to attack us. The hormones flooding into our muscles helped us to summon the strength to throw our spear at the dinosaur, or to run away as fast we could. The hormones also made our senses extra sharp so that we could see and hear and smell acutely, helping us to be extra aware of danger. When we react to the perceived danger of a performance situation, however, we usually don’t literally want to run away or throw a spear at anyone, so that flood of adrenaline may seem counter-productive. However, it can give us a heightened energy that lends that extra “edge” in performance. So our goal shouldn’t be to get rid of the response completely – which we probably can’t do anyway – but to manage it so that it powers our performance rather than sabotages it. -

Types of Anxiety

SAGE Flex for Public Speaking Types of Anxiety Brief: While public speaking is commonly associated with anxiety, not all speakers who experience anxiety experience it for the same reasons or in the same way. Learning Objective: Identify the various types of anxiety as they relate to public speaking. Key Terms: • Anxiety: An unpleasant state of mental uneasiness, nervousness, apprehension and obsession, or concern about some uncertain event. • Context anxiety: Anxiety that triggers communication apprehension due to a specific context. • Performance anxiety: Anxiety, fear, or persistent phobia that may be aroused in an individual by the requirement to perform in front of an audience, whether actually or potentially. • Situational anxiety: A short-term form of anxiety triggered by a specific event, such as public speaking. • Trait anxiety: A consistent tendency to respond with acute anxiety in the anticipation of threatening situation (whether they are actually threatening or not). What is Anxiety? Anxiety can be defined as an unpleasant state of mental uneasiness, nervousness, apprehension and obsession, or concern about some uncertain event. While public speaking is commonly associated with anxiety, not all speakers who experience anxiety experience it for the same reasons or in the same way. There are a number of types of anxiety including situational anxiety, context anxiety, performance anxiety, and trait anxiety. Situational Anxiety Situational anxiety is a short-term psychological reaction sparked by a specific situation—a reaction that may or may not reflect how the person would respond in other contexts. Take for an example the anxiety someone might feel when they go on a first date. -

Anxiety Can Be Considered a Normal and Natural Response to Life’S Challenges

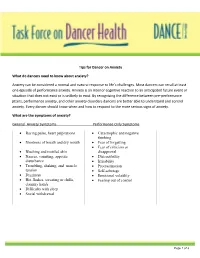

Tips for Dancer on Anxiety What do dancers need to know about anxiety? Anxiety can be considered a normal and natural response to life’s challenges. Most dancers can recall at least one episode of performance anxiety. Anxiety is an interior cognitive reaction to an anticipated future event or situation that does not exist or is unlikely to exist. By recognizing the difference between pre-performance jitters, performance anxiety, and other anxiety disorders dancers are better able to understand and control anxiety. Every dancer should know when and how to respond to the more serious signs of anxiety. What are the symptoms of anxiety? General Anxiety Symptoms Performance Only Symptoms Racing pulse, heart palpitations Catastrophic and negative thinking Shortness of breath and dry mouth Fear of forgetting Fear of criticism or Blushing and mottled skin disapproval Nausea, vomiting, appetite Distractibility disturbance Irritability Trembling, shaking, and muscle Procrastination tension Self-sabotage Dizziness Emotional volatility Hot flashes, sweating or chills, Feeling out of control clammy hands Difficulty with sleep Social withdrawal Page 1 of 3 What causes Anxiety? Anxiety disorders are not the “fault” of the person experiencing them. These disorders are most likely a combination of biological and psychological factors. Biological/physical factors include genetic factors or familial factors and changes in brain chemicals. Psychological factors include the ways dancers learn to think about certain situations or cues, the fears they associate with events and the amount of control they believe they have over situations. Some childhood experiences can have an impact in adulthood reactions to events and shape the way adults deal with anxiety. -

Practice Research. Musician's STAGE FRIGHT. Phoebe Anagnostou

DULWICH CENTRE The Power of Music Using the Power of Music to Reduce Stage Fright in Musicians Phoebe M. Anagnostou 24/6/2017 Phoebe is a psychologist with English and Greek roots who works independently in Greece. She is also a qualified musician who plays the Violoncello and enjoys singing in choirs. Address for correspondence: Phoebe M. Anagnostou 31 Socrates Street Volos 38221 GREECE [email protected] Graduate Certificate in Narrative Therapy, Dulwich Centre, Australia E-learning Program 2016-2017 Abstract This paper illustrates the process of creating a document, which includes musicians’ special ways of reducing stage fright. In this process, musicians’ skills and knowledge that sustain them during anxiety on stage were documented and then shared with other musicians who may have had similar experiences. Engaging narrative practice with this project, this paper suggests that musicians always find a way to enjoy music. Key words: music, anxiety, stage fright, double listening, collective document, enabling contribution Word count: 5,875 2 Introduction Stage fright Apart from the music that we listen to, that can be an enjoyable experience for us, sometimes when a musician is performing this music it is not always combined with these feelings but also with strong anxiety. Many musicians performing live on stage have strong feelings of anxiety and this experience creates stage fright. According to Wilson (2004), stage fright is a situation in which people experience severe anxiety, fear or persistent phobia due to the requirement to perform in front of an audience. Musicians, actors, comedians, politicians or even individuals having to appear in front of an audience for a job interview or for presenting a project, will experience a degree of stage fright. -

62: Β-Adrenergic Antagonists

62: β-Adrenergic Antagonists Jeffrey R. Brubacher HISTORY In 1948, Raymond Alquist postulated that the cardiovascular actions of epinephrine, hypertension and tachycardia, were best explained by the existence of two distinct sets of receptors that he generically named α and β receptors. At that time, the contemporary “antiepinephrine” xenobiotics such as phenoxybenzamine reversed the hypertension but not the tachycardia associated with epinephrine. According to Alquist’s theory these xenobiotics acted at the α receptors. The β receptors, in his schema, mediated catecholamine induced tachycardia. The British pharmacist, Sir James Black was influenced by Alquist’s work and recognized the potential clinical benefit of a β- adrenergic antagonist. In 1958, Black synthesized the first β-adrenergic antagonist, pronethalol. This drug was briefly marketed as Alderlin, named after Alderly Park, the research headquarters of ICI Pharmaceuticals. Pronethalol was discontinued because it produced thymic tumors in mice. Propranolol was soon developed and marketed as Inderal (an incomplete anagram of Alderlin) in the United Kingdom in 1964.22,199 and in the United States in 1973. Prior to the introduction of β- adrenergic antagonists, the management of angina was limited to medications such as nitrates, which reduced preload through dilation of the venous capacitance vessels and increased myocardial oxygen delivery by vasodilation of the coronary arteries. Propranolol gave clinicians the ability to decrease myocardial oxygen utilization. This new approach -

Beta Blockers and Performance Anxiety in Musicians

BETA BLOCKERS AND PERFORMANCE ANXIETY IN MUSICIANS A Report by the beta blocker study committee of FLUTE: Karla Harby, freelance writer and amateur flutist Kathrin Kucharski, clinical pharmacist and amateur flutist Sarah Tuck (committee chair), professional flutist Julia Vasquez, professional flutist Beta blockers have been called "the musicians underground drug." Often musicians form their opinions, and may risk their health, based on locker-room- type information. Performance anxiety can be a deeply personal subject for musicians, and many are reluctant to discuss all the possible remedies. It is our intention to bring this subject into the open, and to provide accurate information to inform personal opinions and decisions. z 1. What are beta blockers (such as Inderal)? Beta blockers block the receptors for the physical effects of a person's natural fight or flight response. They are not sedatives, and they can't help anxiety of a purely psychological nature. Beta receptors are found in a number of places in the body: heart, lung, arteries, brain and uterus, to name a few. Like a key in a lock, beta blockers chemically fit into beta receptors and prevent norepinephrine from binding to the receptors that cause the symptoms of the fight-or-flight response. The degree of these effects depends on the dose and the individual's sensitivity to the medication. Peak effect occurs in one to one and a half hours. Ideally, this could allow a performer to play at his or her best, without the distraction or interference of excessive fight or flight symptoms. Blocking beta receptors can cause decreased heart rate; decreased force of heart contractions; bronchoconstriction (can cause asthma attacks in people with asthma); uterine contractions; decreased blood pressure; relief of migraines; and decreased tremor. -

Treating Anxiety with a Beta Blocker - Antimuscarinic Combination: a Review of Compounded Atenolol - Scopolamine Thomas P Dooley1*, Ashley B Benjamin2 and Ty Thomas3

Review Article iMedPub Journals Clinical Psychiatry 2019 www.imedpub.com Vol.5 No.3:63 ISSN 2471-9854 Treating Anxiety with a Beta Blocker - Antimuscarinic Combination: A Review of Compounded Atenolol - Scopolamine Thomas P Dooley1*, Ashley B Benjamin2 and Ty Thomas3 1Trends in Pharma Development, LLC, 7100 Cabin Lane, Pinson, Alabama, USA 2Department of Psychiatry, Ventura County, California, USA 3National Center for Pain Management and Research, Vestavia Hills, Alabama, USA *Corresponding author: Thomas P Dooley, Trends in Pharma Development, Alabama, USA, Tel: +2052226145; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: November 5, 2019; Accepted date: December 13, 2019; Published date: December 20, 2019 Citation: Dooley TP, Benjamin AB, and Thomas T (2019) Treating Anxiety with a Beta Blocker - Antimuscarinic Combination: A Review of Compounded Atenolol - Scopolamine. Clin Psychiatry Vol.5 No.3:63. is 325.4 million, of which 22.8% are under 18 years of age. Thus, there are 251.2 million adults. The 12-month prevalence Abstract of any anxiety disorder is 18.1%. Therefore, an estimated 45.5 million adults are affected by anxiety disorders in the US. A patented new class of anti-anxiety medications consists of a beta blocker plus an antimuscarinic agent to inhibit While medications such as the SSRI and SNRI the sympathetic and parasympathetic symptoms of antidepressants and the serotonin 1a receptor partial agonist, anxiety disorders, respectively. The PanX® medications buspirone, are approved and widely used as long-term are non-benzodiazepines to address the unmet medical prophylactics for anxiety disorders, the treatment of acute need for fast-acting and effective anxiolytics, without anxiety per se remains a challenge. -

Performance Anxiety and the Benefits of Proper Breathing for Singing

Bellarmine University ScholarWorks@Bellarmine Undergraduate Theses Undergraduate Works 4-27-2018 Performance Anxiety and the Benefits of Proper Breathing for Singing Kate Zecher [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bellarmine.edu/ugrad_theses Part of the Behavioral Disciplines and Activities Commons, Behavior and Behavior Mechanisms Commons, Experimental Analysis of Behavior Commons, Movement and Mind-Body Therapies Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Therapy Commons, Nervous System Commons, and the Respiratory System Commons Recommended Citation Zecher, Kate, "Performance Anxiety and the Benefits of Proper Breathing for Singing" (2018). Undergraduate Theses. 31. https://scholarworks.bellarmine.edu/ugrad_theses/31 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Works at ScholarWorks@Bellarmine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@Bellarmine. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Zecher 1 Performance Anxiety and the Benefits of Proper Breathing for Singing The intent of this thesis is to help those with Music Performance Anxiety, or anxiety in general, better understand their anxiety and its causes. They can then use this knowledge to reduce or control their symptoms in order to improve their performance, whether on a stage or in a classroom. One of the main symptoms of Music Performance Anxiety is constriction of the chest. It is one of the most debilitating symptoms to singers as it causes shortness of breath. Therefore, focusing on anxiety in relation to breathing will most benefit those with Music Performance Anxiety. In addition, learning about the causes and effects of Music Performance Anxiety may help performers with their stage fright whether it be just nervous jitters or debilitating anxiety.