Understanding the Longevity of a Disliked Brand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STEWARDSHIP SUCCESS STORIES and CHALLENGES the Sticky Geranium (Geranium Viscosissimum Var

“The voice for grasslands in British Columbia” MAGAZINE OF THE GRASSLANDS CONSERVATION COUNCIL OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Fall 2007 STEWARDSHIP SUCCESS STORIES AND CHALLENGES The Sticky Geranium (Geranium viscosissimum var. viscosissimum) is an attractive hardy perennial wildflower that can be found in the grasslands of the interior. The plant gets its name from the sticky glandular hairs that grow on its stems and leaves. PHOTO BRUNO DELESALLE 2 BCGRASSLANDS MAGAZINE OF THE GRASSLANDS CONSERVATION COUNCIL OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Fall 2007 The Grasslands Conservation Council of British Columbia (GCC) was established as a society in August 1999 and as a registered charity on December 21, IN THIS ISSUE 2001. Since our beginning, we have been dedicated to promoting education, FEATURES conservation and stewardship of British Columbia’s grasslands in collaboration with 13 The Beauty of Pine Butte Trish Barnes our partners, a diverse group of organizations and individuals that includes Ashcroft Ranch Amber Cowie government, range management specialists, 16 ranchers, agrologists, ecologists, First Nations, land trusts, conservation groups, recreationists and grassland enthusiasts. The GCC’s mission is to: • foster greater understanding and appreciation for the ecological, social, economic and cultural impor tance of grasslands throughout BC; • promote stewardship and sustainable management practices that will ensure the long-term health of BC’s grasslands; and • promote the conservation of representative grassland ecosystems, species at risk and GCC IN -

Heroes of the Storm™ Open Beta Now Live!

The Nexus Beckons: Heroes of the Storm™ Open Beta Now Live! Heroes everywhere are invited to answer the call and tune into the launch celebration event for China on May 31 SHANGHAI, China, May 19, 2015 — It’s time to rally your fellow heroes and let the battles begin! Blizzard Entertainment Inc. and NetEase Inc. today jointly announced that the Nexus portal is wide open to heroes everywhere, as open beta testing for Heroes of the Storm™, its brand-new free-to-play online team brawler for Windows® PC, is now live in China. Heroes of the Storm brings together a diverse cast of iconic characters from Blizzard’s far-flung realms of science fiction and fantasy, including the Warcraft®, StarCraft® and Diablo® universes, to compete in epic, adrenaline-charged battles. Players can download the game and start playing immediately—head over to the official Heroes of the Storm website to get started. “We’re thrilled to finally open the Nexus to everyone,” said Mike Morhaime, CEO and cofounder of Blizzard Entertainment. “We’ve built Heroes of the Storm to be very fun and easy to pick up, with lots of variety and strategic depth through the different characters and battlegrounds. We can’t wait to see the action unfold as new players join in and take 20 years’ worth of Blizzard heroes and villains into battle.” “We're excited to see the all-star lineup from every one of Blizzard's franchises meet up in Heroes of the Storm," said William Ding, CEO and founder of NetEase. “Blizzard has had a huge influence on Chinese players and the local market over the past two decades. -

The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (Guess)

THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) A Dissertation by Mikki Hoang Phan Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Psychology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Mikki Phan All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Psychology. _____________________________________ Barbara S. Chaparro, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Joseph Keebler, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jibo He, Committee Member _____________________________________ Darwin Dorr, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member Accepted for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences _____________________________________ Ronald Matson, Dean Accepted for the Graduate School _____________________________________ Abu S. Masud, Interim Dean iii DEDICATION To my parents for their love and support, and all that they have sacrificed so that my siblings and I can have a better future iv Video games open worlds. — Jon-Paul Dyson v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Althea Gibson once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.” Thus, completing this long and winding Ph.D. journey would not have been possible without a village of support and help. While words could not adequately sum up how thankful I am, I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation chair and advisor, Dr. -

FIFA 20 Para PC Permite-Te Jogar Com Uma Série De Dispositivos De Controlo

ÍNDICE CONTROLOS COMPLETOS 5 FIFA ULTIMATE TEAM (FUT) 22 ESTE ANO, NO FIFA 16 PONTAPÉ DE SAÍDA 27 COMEÇAR A JOGAR 17 CARREIRA 28 COMO JOGAR 18 JOGOS DE PERÍCIA 31 VOLTA FOOTBALL 20 ONLINE 31 O FIFA 20 para PC permite-te jogar com uma série de dispositivos de controlo. Para usufruíres da melhor experiência, recomendamos a utilização do Comando sem fios Xbox One. Os controlos listados ao longo do manual partem do princípio que estás a utilizar um Comando sem fios Xbox One. Se estás a utilizar um comando diferente, tem atenção que na aplicação de Execução do FIFA, se selecionares DEFINIÇÕES DE JOGO > ÍCONES DE BOTÃO, podes alternar entre o estilo de ícones numérico e , , , . Se fores um jogador que utiliza o teclado ou o teclado e o rato, o FIFA 20 para PC também permite-te visualizar os ícones/teclas do teclado no jogo. Isto fica definido quando executas o jogo e chegas ao ecrã que diz: “Prime START ou BARRA DE ESPAÇOS”. Isto define o teu dispositivo de controlo predefinido. Se tiveres um Comando sem fios Xbox One e premires o botão Menu neste momento, verás os ícones de botão que selecionaste na Aplicação de Execução do FIFA previamente mencionada. Se premires a BARRA DE ESPAÇOS neste ecrã, verás os ícones de teclado representados ao longo de todo o jogo. Ao editares o mapeamento de controlo no jogo, tem em atenção que seja qual for o dispositivo com que avanças para entrares nos ecrãs de Definições do Controlador esse será o dispositivo cujos mapeamentos de controlo o jogo te autoriza a ajustar. -

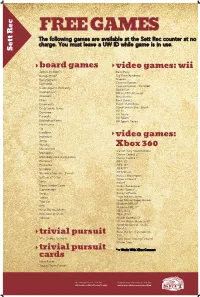

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm. -

Thebestway FIFA 14 | GOOGLE GLASS | PS4 | DEAD MOUSE + MORE

THE LAUNCH ISSUE T.O.W.I.E TO MK ONLY THE BEST WE LET MARK WRIGHT WE TRAVEL TO CHELSEA AND JAMESIII.V. ARGENT MMXIIIAND TALK BUSINESS LOOSE IN MILTON KEYNES WITH REFORMED PLAYBOY CALUM BEST BAG THAT JOB THE ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO HOT HATCH WALKING AWAY WITH WE GET HOT AND EXCITED THE JOB OFFER OVER THE LATEST HATCHES RELEASED THIS SUMMER LOOKING HOT GET THE STUNNING LOOKS ONE TOO MANY OF CARA DEVEVINGNE DO YOU KNOW WHEN IN FIVE SIMPLE STEPS ENOUGH IS ENOUGH? THEBESTway FIFA 14 | GOOGLE GLASS | PS4 | DEAD MOUSE + MORE CONTENTS DOING IT THE WRIGHT WAY - THE TRENDLIFE LAUNCH PARTY The Only Way To launch TrendLife Magazine saw Essex boys Mark Wright and James ‘Arg’ Argent join us at Wonderworld in Milton Keynes alongside others including Corrie’s Michelle Keegen. Take a butchers at page 59 me old china. 14 MAIN FEATURES CALUM BEST ON CALUM BEST We sit down with Calum Best at 7 - 9 Chelsea’s Broadway House to discuss his new look on life, business and of course, the ladies. 12 MUST HAVES FOR SUMMER Get your credit card at the ready as 12 we give you ‘His and Hers’ essentials for this summer. You can thank us later. NEVER MIND THE SMALLCOCK Ladies, you have all been there and if 18 you have not, you will. What do you do when you are confronted with the ultimate let down? Fight or flight? #TRENDLIFEAWARDS REGISTER TODAY FOR THE EVENT OF 2013 WHATS NEW FIFA 14 PREVIEW | 35 No official release date. -

Published 26 February 2019 LKFF 2018

1–25 NOVEMBER LONSM_350_ .pdf 1 2018. 8. 22. �� 8:48 It is my pleasure to introduce to you the 13th instalment of the London Korean Film Festival, our annual celebration of Korean Film in all its forms. Since 2006, the Korean Cultural Centre UK has presented the festival with two simple goals, namely to be the most inclusive festival of national cinema anywhere and to always improve on where we left off. As part of this goal Daily to Seoul and Beyond for greater inclusivity, in 2016 the main direction of the festival was tweaked to allow a broader, more diverse range of Korean films to be shown. With special themes exploring different subjects, the popular strands covering everything from box office hits to Korean classics, as well as monthly teaser screenings, the festival has continued to find new audiences for Korean cinema. This year the festival once again works with critics, academics and visiting programmers on each strand of the festival and has partnered with several university film departments as well. At the time of writing, this year’s festival will screen upwards of 55 films, with a special focus entitled ‘A Slice of Everyday Life’. This will include the opening and closing films, Microhabitat by Jeon Go-woon, and The Return by Malene Choi. C ‘A Slice of Everyday Life’ explores valuable snapshots of the sometimes-ignored M lives of ordinary Koreans, often fragile individuals on the edge of society. One Y will also see director Lee Myung-se's films in the Contemporary Classics strand and Park Kiyong's films in the Indie Firepower strand. -

FIFA 21 Trae Grandes Novedades En El Modo Carrera Y Un Gameplay Más Realista

FIFA 21 trae grandes novedades en el modo carrera y un gameplay más realista Electronic Arts ha revelado las novedades que vendrán en los modos favoritos de los fans de EA SPORTS ™ FIFA 21. Desde más formas de jugar con tus amigos a través de nuevos elementos sociales, hasta tener más control que nunca para administrar cada momento de la carrera, los jugadores pueden experimentar el Juego del Mundo como nunca antes. FIFA 21 también trae una nueva generación de fútbol con Kylian Mbappé del París Saint-Germain, que aparece en la portada de todas las ediciones, disponibles en todo el mundo el 9 de octubre de 2020 para PlayStation 4, Xbox One, PC a través de Origin y Steam. “Estar en la portada de FIFA es un sueño hecho realidad. Desde mi época en Bondy pasando por Clairefontaine hasta la Copa del Mundo, esto marca otro gran hito. He jugado a este juego desde que era un niño y es un honor para mí representar a una generación completamente nueva de futbolistas y estar en el mismo grupo que muchos otros jugadores increíbles con los que ahora comparto este honor”, ha dicho Kylian Mbappé. Jugar al fútbol con amigos es la razón por la que la gente ama tanto el deporte. En FIFA 21, los jugadores pueden saltar a una experiencia de fútbol callejero más social con VOLTA SQUADS, una nueva modalidad para que cuatro jugadores se unan o entren en la comunidad con otros jugadores de FÚTBOL VOLTA y ganen como un equipo en partidos cooperativos online de 5 Vs. -

Fifa 2001 Crack Download 15

Fifa 2001 Crack Download 15 1 / 3 Fifa 2001 Crack Download 15 2 / 3 Fifa 20 PC Download, Full Version, Demo, Gratuit, Telecharger, 17,18,19,16,15 demo. Fifa 20 Download PC, Gratuit, Full Version, Crack, Telecharger. ... FIFA '99, FIFA 2000, FIFA 2001, FIFA 2002, FIFA Football 2003, FIFA Football 2004, FIFA .... FIFA 19 Denuvo Crack Status - Crackwatch monitors and tracks new cracks from CPY, STEAMPUNKS, RELOADED, etc. and sends you an email and phone notification when the games you follow get cracked! ... Lord of the n00bs (15) ..... ted2001. Apprentice (63). military-rank profile. 2. NOPE I WOULD .... Tải game FIFA 2001 (2000) full crack miễn phí - RipLinkNerverDie.. FIFA 2001 (known as FIFA 2001: Major League Soccer in North America) is a 2001 FIFA video game and the sequel to FIFA 2000 and was succeeded by FIFA .... Download FIFA 2001 Demo. This is the ... Serial Link. Null Modem ... FIFA 15. Soccer simulation game for Windows and other platforms. Cue Club thumbnail .... FIFA 15 (Video Pc Game) Highly Compressed Free Download Setup RIP ... List Free Download PC Full Highly Download All FIFA Games including FIFA 2001 2002 ... FIFA 2005 Football PC Game Download From Torrent Soccer Online Free!. Hi this is a realistic !!!!! patch that makes the players and teams that bit more ...... ENGLISH Brazilian adboards (JH Cup) for Fifa 2001 Download size: 15,7KB .... FIFA 20 Denuvo Crack Status - Crackwatch monitors and tracks new cracks from ... i hope they will give us a cracked fifa 20 as gift for Christmas this will be a very big big prize for alot of people .. -

Practice and Adjust FIFA 16 to Solve the Problem of Passing & Pace

Sep 25, 2015 03:54 EDT safewow fifa 16 coins for sale: Practice and Adjust FIFA 16 to Solve the Problem of Passing & Pace FIFA 16 have launched on September 22, 2015. Most players have been playing the game. Nevertheless, gamers come across many difficulties in fifa16 except for how to buy cheap fifa16 coins. In particular, they are complaining about passing or pace. Safewow is your best fifa 16 coins seller,time to buy safe and fast fifa 16 coins with easy steps now! 1. Choose an amount of fifa 16 coins on Safewow and make sure to fill in correct personal and delivery information when checkout. 2. List a player into the transfer market, and set 3 days of the auction duration. 3. Go to our 24/7 Live Help and provide your Account Name, Passwords and Verification Code. 4. Our Live chat will delivery the coins as soon as possible and note you in email or phone once complete the delivery. More details:http://www.safewow.com/news/how-to-buy-fifa-16-coins-cheap- on-safewow-with-fast-delivery/ Some players is complaining fifa 16 too hard FIFA16 comes in these couple days. Nevertheless, problems have appeared a lot in the process of playing fifa16. Maybe due to the new updated games, most gamers complain it difficult to pass or pace. Some players even guess EA will patch it soon. A few players regard their defense of passes which should be appropriately powered, but completely miss their mark. Sometimes, a pass ends up blasting to the other side of the pitch; meanwhile a medium ranged pass happens to just stop after a few meters. -

The Britain Guide 2000 Gratis Epub, Ebook

THE BRITAIN GUIDE 2000 GRATIS Auteur: none Aantal pagina's: none pagina's Verschijningsdatum: none Uitgever: Baeckens Books||9780749522445 EAN: nl Taal: Link: Download hier Independent Hostel Guide 2019 Informatie afkomstig uit de Engelse Algemene Kennis. Bewerk om naar jouw taal over te brengen. United Kingdom. Verwijzingen naar dit werk in externe bronnen. Wikipedia in het Engels Geen. Geen bibliotheekbeschrijvingen gevonden. Haiku samenvatting. Voeg toe aan jouw boeken. Voeg toe aan je verlanglijst. Snelkoppelingen Amazon. Amazon Kindle 0 edities. Audible 0 edities. CD Audiobook 0 edities. Google Books — Bezig met laden Boeken zoeken in uw omgeving. Populaire omslagen. Waardering Gemiddelde : Geen beoordelingen. Ben jij dit? Over Contact LibraryThing. Onlangs toegevoegd door. Voor meer hulp zie de helppagina Algemene Kennis. Gangbare titel. Oorspronkelijke titel. Alternatieve titels. CPC Game Reviews. MIT Press. Ready: A Commodore 64 Retrospective. Routledge Handbook of Modern Japanese Literature. February 26, Indie Nova. Donyaye Bazi Organization. Playing with Videogames. Retrieved 25 April PR Newswire. Future Publishing. November 19, Retrieved October 27, Game Informer. GameStop : August In August , Funcoland began publishing a six-page circular to be handed out free in all of its retail locations. Hardcore Gaming Retrieved October 26, Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on February 10, Entrevistamos a sus creadores y nos recuerdan anécdotas curiosas como el suceso de la katana". El País. Retrieved July 7, Rangeela B. Archived from the original on 27 August Retrieved 2 December Micromania in Spanish. Madrid, Spain. El Mundo in Spanish. Archived from the original on 13 November Retrieved 3 December Louviers 1 August La Informacion in Spanish. Archived from the original on 13 April Complex Gaming. -

Fifa 10 Free Download for Pc Full Version FIFA 21 Download

fifa 10 free download for pc full version FIFA 21 Download. Download FIFA 21 for free – learn how to enjoy the latest instalment of FIFA cycle! F IFA 21 is yet another part of very successful series that allowed us to delve into the virtual world of football. It is a discipline that brings almost everyone behind TV screens or stadiums. No wonder that most of us would like to play the game and feel the incredible emotions all the professional footballers feel. For this reason, we decided to create a very simple access to FIFA 21 download links . It is a great opportunity to test out recently released FIFA game. There are plenty of novelties and features that the authors decided to include, so it is definitely not the same game with another number. If you don’t believe, here is your chance to test it out! What makes FIFA 21 so interesting? Before we tell you more about our installing device and FIFA 21 download links, we should certainly take a closer look at the authors of this game as well as the basics. As we all know, FIFA 21 is yet another instalment that was created by Electronic Arts Sports (known as EA Sports). It is one of the most popular and the most profitable cycles that up to this moment sold in millions of copies. Another part of the game once again allows us to control our favorite club or a footballer . The game introduces several novelties. The most important changes regard the artificial intelligence as well as career game mode.