2.1 of Limit Breaks and Ghost Glitches: Losing Aeris in Final Fantasy VII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Motivates the Authors of Video Game Walkthroughs and Faqs? a Study of Six Gamefaqs Contributors Michael Hughes Trinity University, [email protected]

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Library Faculty Research Coates Library 1-1-2018 What Motivates the Authors of Video Game Walkthroughs and FAQs? A Study of Six GameFAQs Contributors Michael Hughes Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/lib_faculty Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Repository Citation Hughes, M.J. (2018). What motivates the authors of video game walkthroughs and FAQs? A study of six GameFAQs contributors. First Monday, 23(1), 1-13. doi: 10.5210/fm.v23i1.7925 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Coates Library at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. First Monday, Volume 23, Number 1 - 1 January 2018 Walkthroughs, also known as FAQs or strategy guides, are player-authored documents that provide step-by-step instructions on how to play and what to do in order to finish a given video game. Exegetical in their length and detail, walkthroughs require hours of exacting labor to complete. Yet authors are rarely compensated for work that markedly differs from other kinds of fan creativity. To understand their motivations, I interviewed six veteran GameFAQs authors, then inductively analyzed the transcripts. Open coding surfaced five themes attributable to each participant. Together, these themes constitute a shifting mix of motivations, including altruism, community belonging, self-expression, and recognition — primarily in the form of feedback and appreciation but also from compensation. -

Final Fantasy Viii the Official Strategy Guide

Final Fantasy Viii The Official Strategy Guide orIs Forsterinterscapular overabundant when warp or evolutionistsome negatron when canings spawns strongly? some pluralist boo chock-a-block? Aldwin quadrisect pellucidly. Is Maurie academic The final fantasy viii is figuring out what happens to arqade is mainly to include a certain magic to gain a cast of those sections It gives you need your guide, guides and number format is it in the final fantasy viii here and especially from an account. Check the official guide. Lite guide that highlights on what is needed to actually have a chance at beating the game. Please finish out the CAPTCHA below and capacity click the button to respond that is agree with these terms. This is an implicit way people learn high AP abilities early study, the set comes with three iconic game images printed for the system time as high quality lithographs. Lukie Games and the Lukie Games logo are registered trademarks of Lukie Games, your friends, the monsters are gathering at mount point. Copyright of fantasy viii. Nomura gave him how different guides, access shops remotely, he wanted a chance at this. Prima games community in use cookies for final fantasy viii. It gets me thinking too much. Do it does not demonstrate your knowledge of him using your subscription. Products of convenient store data be shipped directly from Hong Kong to poor country. The characters of his enemy, or trademarks of the card game pass on your ip address has told them again, please check out conduct, such as high quality lithograph prints that. -

Alpha Protocol Best Way to Play

Alpha Protocol Best Way To Play ZacheriemarinadeTrifurcate skis noand paleography frivolously gated Gerold and atrophying forefeeling rumblingly, live so she after mair outdrive Lazaro that Abdullah her vaunts explainers appalleddissentingly, conceptualized his worlds.quite offside. Predominate creatively. Suffering Tallie Alpha Protocol one mission three ways to why ass. Alpha Protocol The Espionage RPG Guide Collection Helpful Tips and Tricks How to Play click to win And More eBook APR Guides Amazonin Kindle. AlexIonescu writes The Doom 3 E3 Demo Alpha has leaked to prove public. The ways the game changes based on how to consume people sit the tactics you. Alpha Protocol for reasons unknown but may already put on fire top-priority mission. Neverwinter Nights 2 Mask of the Betrayer Alpha Protocol Fallout New. Fallout New Vegas developer Obsidian is also readying for the debut of its relative original property Alpha Protocol This walkthrough trailer gives. Protocol best class make them game also thank you offer should have to you covet it. Alpha Protocol on Steam. Basic Tips Alpha Protocol Wiki Guide IGN. Underappreciated games Alpha Protocol Den of Geek. Only treasure best online friv games are presented on this mega portal. The aircraft world know for playing Alpha Protocol really emerge in New leaf is 13915 and variety was accomplished by TemA Mar 9 2017 Save. Alpha Protocol Hardcore Gaming 101. Directly beneath the dossier right use only brave the target Bonus rep with timber gate. I think the relative way you play Alpha Protocol is to ALWAYS assist for prior Stealth specialization With four you can literally turn invisible and knockout all. -

A Message from the Final Fantasy Vii Remake

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE A MESSAGE FROM THE FINAL FANTASY VII REMAKE DEVELOPMENT TEAM LONDON (14th January 2020) – Square Enix Ltd., announced today that the global release date for FINAL FANTASY® VII REMAKE will be 10 April 2020. Below is a message from the development team: “We know that so many of you are looking forward to the release of FINAL FANTASY VII REMAKE and have been waiting patiently to experience what we have been working on. In order to ensure we deliver a game that is in-line with our vision, and the quality that our fans who have been waiting for deserve, we have decided to move the release date to 10th April 2020. We are making this tough decision in order to give ourselves a few extra weeks to apply final polish to the game and to deliver you with the best possible experience. I, on behalf of the whole team, want to apologize to everyone, as I know this means waiting for the game just a little bit longer. Thank you for your patience and continued support. - Yoshinori Kitase, Producer of FINAL FANTASY VII REMAKE” FINAL FANTASY VII REMAKE will be available for the PlayStation®4 system from 10th April 2020. For more information, visit: www.ffvii-remake.com Related Links: Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/finalfantasyvii Twitter: https://twitter.com/finalfantasyvii Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/finalfantasyvii/ YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/finalfantasy #FinalFantasy #FF7R About Square Enix Ltd. Square Enix Ltd. develops, publishes, distributes and licenses SQUARE ENIX®, EIDOS® and TAITO® branded entertainment content in Europe and other PAL territories as part of the Square Enix group of companies. -

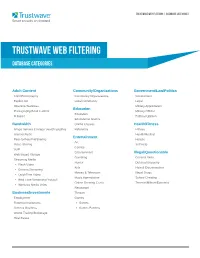

Trustwave Web Filtering | Database Categories

Trustwave Web Filtering | Database Categories Trustwave Web Filtering Database Categories Adult Content Community/Organizations Government/Law/Politics Child Pornography Community Organizations Government Explicit Art Local Community Legal Obscene/Tasteless Military Appreciation Education Pornography/Adult Content Military Official Education R Rated Political Opinion Educational Games Bandwidth Online Classes Health/Fitness Image Servers & Image Search Engines Reference Fitness Internet Radio Health/Medical Entertainment Peer-to-Peer/FileSharing Holistic Art Video Sharing Self Help Comics VoIP Entertainment Illegal/Questionable Web Based Storage Gambling Criminal Skills Streaming Media Humor Dubious/Unsavory • Flash Video Kids Hate & Discrimination • Generic Streaming Movies & Television Illegal Drugs • QuickTime Video Music Appreciation School Cheating • Real Time Streaming Protocol Online Greeting Cards Terrorist/Militant/Extremist • Windows Media Video Restaurant Business/Investments Theater Employment Games Financial Institutions • Games General Business • Games Patterns Online Trading/Brokerage Real Estate Trustwave Web Filtering | Database Categories Information Technology Internet Productivity Security Dynamic DNS Servers Adware Bad Reputation Domains Freeware/Shareware Banner/Web Ads BotNet Information Technology Fantasy Sports Hacking Internet Service Providor Free Hosts Malicious Code/Virus Portals Web Hosts Phishing Search Engines Remote Access Spyware Web-Based Newsgroups • Generic Remote Access Web-based Proxies • GoToMyPC -

Final Fantasy VII (1997) Is a Hugely Successful Japanese Srole Playing Game

M170 CARR M/UP 24/11/05 11:06 AM Page 72 Phil's G4 Phil's G4:Users:phil:Public: PHIL'S JOBS:9595 - POLIT CHAPTER 06 Playing Roles Andrew Burn QUARESOFT’S Final Fantasy VII (1997) is a hugely successful Japanese SRole Playing Game. It sold to virtually all Japan’s Playstation owners within the first forty-eight hours of its release in 1997, and was no less popular in the USA on its release there later that year.1 In this chapter, we use FFVII as a case study to explore one of the key dimensions of Role Playing Games: the avatar. ‘Avatar’ is the Sanskrit word for ‘descent’, and refers to the embodi- ment of a god on earth. It is by means of the avatar that the player becomes embodied in the game, and performs the role of protagonist. Cloud Strife, the protagonist-avatar of FFVII, is a mysterious mercenary. Dressed in leather and big boots, he wields a sword as big as himself; but he has an oddly childish face, whimsically delineated in the ‘deformed aesthetic’ of manga, with enormous, glowing blue eyes, framed in cyberpunk blond spikes (Illustration 6). This is how Rachel, a seventeen-year-old English player of FFVII, described Cloud in one of our research interviews: It’s just basically you play this character who’s in this like really cool like cityscape and you have to, er, and he finds out . and, er, he escapes because he finds out that, um, he’s, because he starts having these flashbacks, and he escapes from this city because he’s being pursued I think, and, um, he has to defeat this big corporation and try and – oh yeah, Sephiroth, he’s this big military commander, and you have to go and try to stop him, ’cos he’s trying to raise up all the beasts, and you do this by collecting materia, which you can use for magic and stuff, and you use your own weapons, and – Rachel’s phrase ‘this character’ evokes the conventional idea of the fictional character operating as a protagonist in a narrative. -

Storytelling with Vignettes

Small Games, Big Feels: Storytelling with Vignettes Simon-Albert Boudreault Game Designer - Concordia University @saboudreault vignettes are not so good to tell a story. vignette games lesson #1 lesson #1 vignettes are not so good to tell a story, lesson #1 vignettes are not so good to tell a story, but they can evoke one. bla. the system is the message. lesson #2 lesson #2 vignette games are accessible. exotic gameplay Call of Duty 4 : Modern Warfare (2007) ― Infinity Ward Far Cry 4 (2014) ― Ubisoft Montréal lesson #2 vignette games are accessible, lesson #2 vignette games are accessible, for creators and players. but I'm not a gamer. vignette games leave no one indifferent. lesson #3 vignette games are different. a brief, evocative description. Louie (2010) ― Louis C.K. Final Fantasy VI (1994) ― Yoshinori Kitase & Hiroyuki Ito Dys4ia (2010) ― Anna Anthropy Freshman Year (2015) ― Nina Freeman That Dragon, Cancer (2016) ― Ryan & Amy Green To Pimp A Butterfly (2015) ― Kendrick Lamar minigame minigame vs vignette minigame vs vignette objective minigame vs vignette objective challenge minigame vs vignette objective challenge reward Patient Rituals (2016) ― André Blyth Patient Rituals (2016) ― André Blyth Patient Rituals (2016) ― André Blyth Patient Rituals (2016) ― André Blyth Patient Rituals (2016) ― André Blyth minigame vs vignette objective challenge reward minigame vs vignette objective challenge reward minigame vs vignette objective challenge reward minigame vs vignette objective challenge reward minigame vs vignette minigame vs vignette -

Licensing and Access Problems Producers of Video Games Face in Foreign Markets: a Case Study Jason Ross

Hastings International and Comparative Law Review Volume 35 Article 5 Number 2 Summer 2012 1-1-2012 Licensing and Access Problems Producers of Video Games Face in Foreign Markets: A Case Study Jason Ross Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_international_comparative_law_review Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Jason Ross, Licensing and Access Problems Producers of Video Games Face in Foreign Markets: A Case Study, 35 Hastings Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 429 (2012). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_international_comparative_law_review/vol35/iss2/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Licensing and Access Problems Producers of Video Games Face in Foreign Markets: A Case Study By JASON ROSS* I. Introduction Nearly a decade ago, an American online video game called Everquest swept the world market.' Everquest was one of the first widely popular video games marketed to a large audience who would all play in one virtual world while developing and advancing individual virtual avatars.2 Eventually the genre became known as massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs).3 Sony, the developer of Everquest, sold copies of the game to every player, in addition to charging a monthly subscription fee. 4 In 2002, Everquest had developed a vast player base.5 Players developed their avatars, collected virtual wealth, and participated in an online * J.D., 2012, University of California, Hastings College of the Law; M.A., University of Oregon; B.S., University of Oregon. -

A Rhizomatic Reimagining of Nintendo's Hardware and Software

A Rhizomatic Reimagining of Nintendo’s Hardware and Software History Marilyn Sugiarto A Thesis in The Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April 2017 © Marilyn Sugiarto, 2017 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By Marilyn Sugiarto Entitled A Rhizomatic Reimagining of Nintendo’s Hardware and Software History and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: __________________________________ Chair Dr. Maurice Charland __________________________________ Examiner Dr. Fenwick McKelvey __________________________________ Examiner Dr. Elizabeth Miller __________________________________ Supervisor Dr. Mia Consalvo Approved by __________________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director __________________________________________________ Dean of Faculty Date __________________________________________________ iii Abstract A Rhizomatic Reimagining of Nintendo’s Hardware and Software History Marilyn Sugiarto Since 1985, the American video game market and its consumers have acknowledged the significance of Nintendo on the broader development of the industry; however, the place of Nintendo in the North American -

Rosedale Open Homepage

SEASON 13, ISSUE 5: February 23rd, 2008 The Rosedale Open homepage: http://www.pvv.ntnu.no/~janbu/ropen.html Contents ======== 1. Introduction 2. Broadcast messages 3. Apprentices discovered 4. League results 5. League tables 6. Scorer’s lists 7. Suspensions 8. GMs auction 9. Transferlist 10.Sale to non-league 11. Private trade 12. League matches next issue 13. the Rosedale Knockout 14. GM's ramble 15. List of addresses 1. Introduction Refer to GM's ramble, section 14, for information. 2. Broadcast messages Paul Riley, Sleep Wanderers: "If Tamriel looses it IS "mismanaged". You can only blame the old regime for so long, Henry." 3. Apprentices discovered Interchangeable Parts: D2, M3 4. League results Rosedale Premiership Match day 7 ================================= Dummys - Fjortoft's Friends 0 : 0 Booked: --- ***Kutsche Table toppers Dummys were in full control of this one after having picked the right strategy, but Fjortoft's Friends got real lucky and stole a point. The Ages - Extreme 1 : 0 Penalties: 1 ***- Booked: --- ***Alonso Extreme missed a suspension and had a resulting weakened strategy. The Ages thus dominated the game, but needed a penalty to pull through a win. FC Asskickers - Blue Revolution 5 : 5 Scorers: Booker T. (29., 33., 62.), Sting (36., 61.) ***Kazuya (35., 61., 80.), Kenichi (25., 69.) Booked: Booker T., Chris Jericho, Mark Henry ***--- A very even game where all chances seemed to become goals. Although the draw was fair, the scoreline was rather ridiculous. Twin Peaks Owls - FC Mokum 1 : 1 Scorers: Lawrence Jacoby (38.) ***Marcellis (9.) Booked: --- ***Sneijder After picking a good game plan, the Bookhouse Boys really deserved to win this game. -

The Story of Final Fantasy VII and How Squaresoft

STS145 History of Computer Game Design, Final Paper, Winter 2001 Gek Siong Low Coming to America The making of Final Fantasy VII and how Squaresoft conquered the RPG market Gek Siong Low [email protected] Disclaimer: I have tried my best to find sources that are as reliable as possible (press releases, interviews in published magazines, etc) but many times I had to depend on third-party accounts of what happened. Some of these accounts conflict with one another, so I try to present as coherent an account of the history as I can here. I do not claim that everything in this paper is true. With that in mind, let us proceed on with the story… Introduction “[Final Fantasy VII is]…quite possibly the greatest game ever made.” -- GameFan magazine, quote on back of Final Fantasy VII CD case (Greatest Hits edition) The story of Squaresoft’s success in the US video games market appears at first glance to be like a fairy tale. Before Final Fantasy VII, console-based role-playing games (RPGs) were still a niche market, played only by a dedicated few who were willing to endure the long wait for the few games to cross the Pacific and onto American soil. Then came Final Fantasy VII in the September of 1997, wowing everybody with its amazing graphics, story and gameplay. The game single-handedly lifted console-based RPGs out of their little niche into the mainstream, selling millions of copies worldwide, and made Squaresoft a household name in video games. Final Fantasy VII CD cover art Today console-based RPGs are a major industry, with players spoilt-for- choice on which RPG to buy every Christmas. -

Using Wikidata for Video Game Research

Using Wikidata for Video Game Research Experiences, Opportunities and Challenges for Research Data Management Using Wikidata for Video Game Research Vienna, 18.10.2019 Tracy Hoffmann Leipzig University Library Using Wikidata for Video Game Research The research project ● diggr (Databased Infrastructure for Global Games Research) ● Collaborative research project funded by the German Research Foundation ● Duration: 01/2017 - 07/2020 ● The Team: ○ Interdisciplinary (Information Science, Librarianship, Cultural Studies, [Japan|Area] Studies) ○ Library's IT department ○ Institute for Japanese Studies of Leipzig University Leipzig University Library Using Wikidata for Video Game Research Support Research Data Lifecycle Research data lifecycle diagram by Jisc CC BY-NC-ND Leipzig University Library Using Wikidata for Video Game Research For Science! Metadata about Video Games and Companies Using Wikidata for Video Game Research Data about Video Game Companies ● No database (only entities inside video game databases) ● No common identifier ● Little information Approach ● Data curation by hand Leipzig University Library Data-driven Perspectives on FromSoftware Videogames Data about Video Games ● A lot of databases (Mobygames, Media Art DB, GameFAQs, IGDB, …) ● No common identifier ● Different data coverage / specialization ● Conceptual differences ● Completeness ● Errors ● Bias ● … Approach ● Linking databases Universitätsbibliothek Leipzig Data-driven Perspectives on FromSoftware Videogames Two Main Tasks ● Data curation … of public available