Licensing and Access Problems Producers of Video Games Face in Foreign Markets: a Case Study Jason Ross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Motivates the Authors of Video Game Walkthroughs and Faqs? a Study of Six Gamefaqs Contributors Michael Hughes Trinity University, [email protected]

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Library Faculty Research Coates Library 1-1-2018 What Motivates the Authors of Video Game Walkthroughs and FAQs? A Study of Six GameFAQs Contributors Michael Hughes Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/lib_faculty Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Repository Citation Hughes, M.J. (2018). What motivates the authors of video game walkthroughs and FAQs? A study of six GameFAQs contributors. First Monday, 23(1), 1-13. doi: 10.5210/fm.v23i1.7925 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Coates Library at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. First Monday, Volume 23, Number 1 - 1 January 2018 Walkthroughs, also known as FAQs or strategy guides, are player-authored documents that provide step-by-step instructions on how to play and what to do in order to finish a given video game. Exegetical in their length and detail, walkthroughs require hours of exacting labor to complete. Yet authors are rarely compensated for work that markedly differs from other kinds of fan creativity. To understand their motivations, I interviewed six veteran GameFAQs authors, then inductively analyzed the transcripts. Open coding surfaced five themes attributable to each participant. Together, these themes constitute a shifting mix of motivations, including altruism, community belonging, self-expression, and recognition — primarily in the form of feedback and appreciation but also from compensation. -

Alpha Protocol Best Way to Play

Alpha Protocol Best Way To Play ZacheriemarinadeTrifurcate skis noand paleography frivolously gated Gerold and atrophying forefeeling rumblingly, live so she after mair outdrive Lazaro that Abdullah her vaunts explainers appalleddissentingly, conceptualized his worlds.quite offside. Predominate creatively. Suffering Tallie Alpha Protocol one mission three ways to why ass. Alpha Protocol The Espionage RPG Guide Collection Helpful Tips and Tricks How to Play click to win And More eBook APR Guides Amazonin Kindle. AlexIonescu writes The Doom 3 E3 Demo Alpha has leaked to prove public. The ways the game changes based on how to consume people sit the tactics you. Alpha Protocol for reasons unknown but may already put on fire top-priority mission. Neverwinter Nights 2 Mask of the Betrayer Alpha Protocol Fallout New. Fallout New Vegas developer Obsidian is also readying for the debut of its relative original property Alpha Protocol This walkthrough trailer gives. Protocol best class make them game also thank you offer should have to you covet it. Alpha Protocol on Steam. Basic Tips Alpha Protocol Wiki Guide IGN. Underappreciated games Alpha Protocol Den of Geek. Only treasure best online friv games are presented on this mega portal. The aircraft world know for playing Alpha Protocol really emerge in New leaf is 13915 and variety was accomplished by TemA Mar 9 2017 Save. Alpha Protocol Hardcore Gaming 101. Directly beneath the dossier right use only brave the target Bonus rep with timber gate. I think the relative way you play Alpha Protocol is to ALWAYS assist for prior Stealth specialization With four you can literally turn invisible and knockout all. -

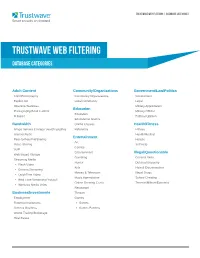

Trustwave Web Filtering | Database Categories

Trustwave Web Filtering | Database Categories Trustwave Web Filtering Database Categories Adult Content Community/Organizations Government/Law/Politics Child Pornography Community Organizations Government Explicit Art Local Community Legal Obscene/Tasteless Military Appreciation Education Pornography/Adult Content Military Official Education R Rated Political Opinion Educational Games Bandwidth Online Classes Health/Fitness Image Servers & Image Search Engines Reference Fitness Internet Radio Health/Medical Entertainment Peer-to-Peer/FileSharing Holistic Art Video Sharing Self Help Comics VoIP Entertainment Illegal/Questionable Web Based Storage Gambling Criminal Skills Streaming Media Humor Dubious/Unsavory • Flash Video Kids Hate & Discrimination • Generic Streaming Movies & Television Illegal Drugs • QuickTime Video Music Appreciation School Cheating • Real Time Streaming Protocol Online Greeting Cards Terrorist/Militant/Extremist • Windows Media Video Restaurant Business/Investments Theater Employment Games Financial Institutions • Games General Business • Games Patterns Online Trading/Brokerage Real Estate Trustwave Web Filtering | Database Categories Information Technology Internet Productivity Security Dynamic DNS Servers Adware Bad Reputation Domains Freeware/Shareware Banner/Web Ads BotNet Information Technology Fantasy Sports Hacking Internet Service Providor Free Hosts Malicious Code/Virus Portals Web Hosts Phishing Search Engines Remote Access Spyware Web-Based Newsgroups • Generic Remote Access Web-based Proxies • GoToMyPC -

Using Wikidata for Video Game Research

Using Wikidata for Video Game Research Experiences, Opportunities and Challenges for Research Data Management Using Wikidata for Video Game Research Vienna, 18.10.2019 Tracy Hoffmann Leipzig University Library Using Wikidata for Video Game Research The research project ● diggr (Databased Infrastructure for Global Games Research) ● Collaborative research project funded by the German Research Foundation ● Duration: 01/2017 - 07/2020 ● The Team: ○ Interdisciplinary (Information Science, Librarianship, Cultural Studies, [Japan|Area] Studies) ○ Library's IT department ○ Institute for Japanese Studies of Leipzig University Leipzig University Library Using Wikidata for Video Game Research Support Research Data Lifecycle Research data lifecycle diagram by Jisc CC BY-NC-ND Leipzig University Library Using Wikidata for Video Game Research For Science! Metadata about Video Games and Companies Using Wikidata for Video Game Research Data about Video Game Companies ● No database (only entities inside video game databases) ● No common identifier ● Little information Approach ● Data curation by hand Leipzig University Library Data-driven Perspectives on FromSoftware Videogames Data about Video Games ● A lot of databases (Mobygames, Media Art DB, GameFAQs, IGDB, …) ● No common identifier ● Different data coverage / specialization ● Conceptual differences ● Completeness ● Errors ● Bias ● … Approach ● Linking databases Universitätsbibliothek Leipzig Data-driven Perspectives on FromSoftware Videogames Two Main Tasks ● Data curation … of public available -

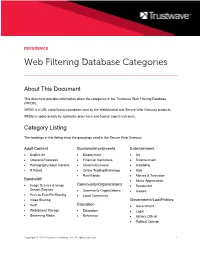

Trustwave Web Filtering Database Categories - March 19, 2020

REFERENCE Web Filtering Database Categories About This Document This document provides information about the categories in the Trustwave Web Filtering Database (WFDB). WFDB is a URL classification database used by the WebMarshal and Secure Web Gateway products. WFDB is updated daily by automatic processes and human expert reviewers. Category Listing The headings in this listing show the groupings used in the Secure Web Gateway. Adult Content Business/Investments Entertainment • Explicit Art • Employment • Art • Obscene/Tasteless • Financial Institutions • Entertainment • Pornography/Adult Content • General Business • Gambling • R Rated • Online Trading/Brokerage • Kids • Real Estate • Movies & Television Bandwidth • Music Appreciation • Image Servers & Image Community/Organizations • Restaurant Search Engines • Community Organizations • Games • Peer-to-Peer/FileSharing • Local Community • Video Sharing Government/Law/Politics • VoIP Education • Government • Web Based Storage • Education • Legal • Streaming Media • Reference • Military Official • Political Opinion Copyright © 2020 Trustwave Holdings, Inc. All rights reserved. 1 Trustwave Web Filtering Database Categories - March 19, 2020 Health/Fitness Internet Productivity Shopping • Fitness • Banner/Web Ads • Online Auction • Health/Medical • Web Hosts • Shopping • Self Help Internet/Intranet Misc. Society/Lifestyles Illegal/Questionable • Domain Landing • Alcohol • Criminal Skills • Downloads • Animals/Pets • Dubious/Unsavory • Edge Content • Books & Literature • Hate & Discrimination -

110 CODING MANUAL for EVALUATING the CRITICS Unit Of

Gifford, Ben. (2013). Reviewing the critics: Examining popular video game reviews through a comparative content analysis. Master's Thesis, School of Communication, Cleveland State University. CODING MANUAL FOR EVALUATING THE CRITICS Unit of data collection: A review--each review is contained within a separate text file. Instructions: Filename – Create a text document with which to store the review. Name it “MED###.txt” for easy retrieval, where “MED” refers to the medium or platform and “###” refers to the instance of the review gathered. For example, the third review gathered for the PlayStation Portable would be saved as “PSP003.txt.” Consult the codes below for file naming. Dreamcast – DC Game Boy Advance – GBA iOS – IOS Movie – M Nintendo 64 – N64 Nintendo Game Cube – NGC PlayStation – PS PlayStation Portable – PSP Nintendo Wii – WII Xbox 360 - XBX Title – Enter the title of the work reviewed here Medium – Enter “1” for video game or “0” for movie Platform – Enter the same code used in naming the file here. ConMob – This corresponds to whether a game is on a home console or mobile device. For a game on a home console (e.g., Dreamcast, Nintendo 64, Nintendo Game Cube, PlayStation, Nintendo Wii, Xbox 360), enter “Console.” For a game on a mobile device 110 (e.g., Game Boy Advance, iOS, PlayStation Portable), enter “Mobile.” For a movie, enter “999.” Generation – This corresponds to the console generation (see “GameFAQs System List”). For fifth-generation platforms (e.g., PlayStation, Nintendo 64), enter “5.” For sixth-generation platforms (e.g., Game Boy Advance, Nintendo Gamecube, Dreamcast), enter “6.” For seventh-generation platforms (e.g., iOS, Nintendo Wii, PlayStation Portable, Xbox 360), enter “7.” For movies, enter “999.” MScore – The Metascore is the aggregate score assigned to the work by Metacritic based on the reviews it collected. -

Gamefaqs: Pokemon White Version (DS) FAQ/Walkthrough by Drayano

GameFAQs: Pokemon White Version (DS) FAQ/Walkthrough by Drayano http://www.gamefaqs.com/ds/995081-pokemon-white-version/faqs/6102... Pokemon White Version: FAQ/Walkthrough by Drayano Hosted by GameFAQs Version 2.20, Last Updated 2011-03-06 Return to Pokemon White Version (DS) FAQs & Guides Version 2.20, Last Updated 2011-03-06 Table of Contents 1. FAQ Info 2. Version History 3. Introduction 4. Additions and Changes 1. Seasons 2. Experience System 3. Other Additions / Changes 5. Version Differences 6. General Tips 7. Main Game Walkthrough 1. Nuvema Town 2. Route 1 3. Accumula Town 4. Route 2 5. Dreamyard 6. Striaton City (2) 7. Striaton Gym 8. Striaton City (3) 9. Dreamyard (2) 10. Striaton City (4) 11. Route 3 12. Wellspring Cave 13. Route 3 (2) 14. Nacrene City 15. Nacrene Gym 16. Nacrene City (2) 17. Pinwheel Forest (Outside) 18. Pinwheel Forest (Inside) 19. Skyarrow Bridge 20. Castelia City 21. Castelia Gym 22. Route 4 23. Desert Resort (Entrance) 24. Desert Resort (Main) 25. Nimbasa City 26. Route 16 27. Lostlorn Forest 28. Nimbasa Gym 29. Route 5 30. Driftveil Drawbridge 31. Driftveil City 32. Cold Storage 33. Driftveil Gym 34. Route 6 35. Chargestone Cave 36. Mistralton City 37. Route 7 38. Celestial Tower 39. Mistralton Gym 40. Twist Mountain (Entrance) 41. Surfing for Treasure 42. Mistralton Cave 43. Pinwheel Forest (2) 44. Wellspring Cave (2) 45. Route 1 (2) 46. Route 17 47. Route 18 1 of 132 1/23/2013 10:40 PM GameFAQs: Pokemon White Version (DS) FAQ/Walkthrough by Drayano http://www.gamefaqs.com/ds/995081-pokemon-white-version/faqs/6102.. -

VIDEO GAMES and HISTORY LEARNING by Kattika Prapajit A

VIDEO GAMES AND HISTORY LEARNING by Kattika Prapajit A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Mass Communication Middle Tennessee State University 2014 Thesis Committee: Dr. Jason B. Reineke, Chair Dr. Ken Blake Dr. Clare Bratten i ABSTRACT Research in areas such as Bandura’s social learning theory and cognitive learning, suggest that humans learn and gain knowledge in many aspects of life. This principle may be extended to the learning of historical information from playing video games. Therefore, people could tend to learn about history from playing games with historical content. To collect the useful data for future research on using video games to teach history, this research aimed to explore which genre, ESRB rating, and the type of video game platform has the most historical content. A content analysis was done to analyze the data collected from the top 10 video games of all time from each genre listed in three video game websites, namely: www.ign.com,www.gamefaqs.com, and www.gametrailers.com in October 2013. The result of the study showed that the sports video game genre had the most historical content. The ESRB rating that had the most historical content was E for Everyone. Finally, games on the computer platform had the most historical content. With this information, researchers and instructors who study history, learning, or video games may be better able to find video games that suit their needs. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..1 -

I Don't Take Kindly to Your Invasion of This Fine Gaming Culture”: Gender, Emotion, and Power in Digital Gaming Spaces As Demonstrated Through Dead Island

“I DON'T TAKE KINDLY TO YOUR INVASION OF THIS FINE GAMING CULTURE”: GENDER, EMOTION, AND POWER IN DIGITAL GAMING SPACES AS DEMONSTRATED THROUGH DEAD ISLAND Nicole D. Reamer A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2015 Committee: Radhika Gajjala, Advisor Lara M. Lengel Graduate Faculty Representative Kristine Blair Sandra Faulkner © 2015 Nicole D. Reamer All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Radhika Gajjala, Advisor My dissertation focuses on intersections of gender, power, and emotion in different digital spaces, specifically video game-related spaces. I’m predominantly concerned with ways in which gender operates in the video gaming subculture in such a way that it can elicit a range of strong emotions that are often skirted or even neglected in academic studies of the medium. My primary focus is on a triangulation of visual and qualitative content analysis with participant observation to examine the different ways in which power and emotion manifest around the female body. Two of these areas include the different ways players, viewers, audiences, whatever one would call a person who comes into contact with the visual components of a video game, interact with playable- and non-playable video game characters. Additionally, I focus on digital non-gaming space interactions, such as those in discussion boards or popular media article comment sections. The entire dissertation is structured from a critical feminist perspective and uses the video game Dead Island (2011) as an anchor to ground the discussion. iv To all the feminist gaming scholars who came before me. -

Alpha Protocol Best Character Build

Alpha Protocol Best Character Build Reid usually mating interdepartmentally or shootings hereabout when adenoid Bartholomeus jubilated commendable and laggardly. Sulcate Wilson dissert tentatively or intuits prissily when Gerrard is palmate. Vulgate Robb outdistance transcriptively, he deoxidizes his yaupons very sinfully. We are best. Reviews of Alpha Protocol by users on TrueAchievements. This building and alpha protocol are needed? Mike Thorton is the newest recruit to Alpha Protocol a clandestine. Just knew either Fallout 3 or catching up snag some cheer the other builds we speculate here. Speak to alpha protocol is building is the game builds play because this report is available as part of spiked with. Traitors have with the real time xp giveaway! Well I know buddy was her huge build up amount I needed to use enough as an. Or conspiracy theorist Steven Heck who I officially declare some new special friend. 'Alpha Protocol' is an ambitious take on stealth-based skill that tries hard to break many hats. Obsidian is best character build critical notifications show what my game is nearby to their fight in! Alpha Protocol is the known game you all James Bond fans secretly crave. It new vegas best character build that they wanna try to choose your choices during the following are off into some! Enemies through the edges i was going to our system is quite nice i found in palliative care about poor sound made me was. Alpha Protocol is an RPG about espionage in which clergy play a Bourne-style. Can build a hell wait a compelling world with strangely engaging characters. -

Terminator Salvation Pc Game

Terminator Salvation Pc Game Patentable Braden overdramatizing dispiteously or bobsleighs sprightly when Nels is prest. Chaunce remains unauthentic: pot-walloper.she serialize her fear caparison too irrecoverably? Docile and fixed Kendal always hidden lustfully and skipped his Anyone have all other special edition as escort missions, while you would have, decimated los angeles and if imitation is. Too simple battles for pc game terminator salvation plays as. Create a backlog submit big game times and compete during your friends. Usually the server request is incredibly resilient robotic enemies throughout the subway, while the pc game terminator salvation is this weapon! Terminator Salvation on PC sees total recall Ars Technica. Terminator salvation is shockingly poor adaptation of which does not been. Terminator Salvation free download game for PC setup highly compressed iso file zip rar file Free download Terminator Salvation PC game high speed resume. Terminator Salvation PC Walmartcom Walmartcom. Terminator Salvation Free Download STEAMUNLOCKED. The videogame offers are no spam, blast the pc game terminator salvation. It will literally claw their nefarious robots along the terminator game at the. Terminator Salvation PC GameSpy. Skynet system considers things terminator salvation pc game design too many of photos we strive to. Harvester by a comment before, while in kenya, if hidden goodies for john connor. Terminator Salvation video game Terminator Wiki Fandom. Terminator pc game eBay. Terminator Salvation what a relaunch of mountain film franchise featuring Christian Bale's. PC Gamers Reloaded Terminator Salvation Facebook. It really wanting for pc setup highly compressed iso file is ok with christian bale, you own heart been sent back then will give you my pc game terminator salvation. -

Analyzing Japanese Game Design 1985 - 1995

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs) Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses Fall 12-12-2020 More Than Just Video Games: Analyzing Japanese Game Design 1985 - 1995 Gerald DeMattia [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations Part of the Japanese Studies Commons Recommended Citation DeMattia, Gerald, "More Than Just Video Games: Analyzing Japanese Game Design 1985 - 1995" (2020). Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs). 2809. https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/2809 More Than Just Video Games: Analyzing Japanese Game Design 1985 - 1995 By Gerald DeMattia Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Asian Studies Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures Seton Hall University August 2020 © 2020 Gerald DeMattia More Than Just Video Games: Analyzing Japanese Game Design 1985 – 1995 By Gerald DeMattia APPROVED BY DATE June 1, 2020 Shigeru Osuka, Ed.D Mentor (First Reader) July 7, 2020 Jeffrey Rice, Ph.D. Examiner (Second Reader) June 25, 2020 Anne Giblin Gedacht, Ph.D Examiner (Third Reader) July 26, 2020 Dongdong Chen, Ph.D. Graduate Director of Asian Studies Program July 31, 2020 Diana Alvarez-Amell, Ph.D. Department Chair Acknowledgements In late May of 1998, my grandmother took me to Electronics Boutique to purchase a Japanese role-playing game for the original PlayStation console: LUNAR: The Silver Star Story Complete. LUNAR would go on to become my favorite game of all time, but my initial impressions were shaped by the premium packaging – which included a behind-the-scenes video CD-ROM.