The Race Science of J. Philippe Rushton : Professors, Protesters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ministry of the Environmental Review Or Individual Environmental Environment’S (MOE, March 2001) “Guide to Environmental Assessment

NOTICE OF COMPLETION OF ENVIRONMENTAL SCREENING FOR THE PROPOSED ADELAIDE WIND FARM Air Energy TCI Inc (AET) has completed an environmental The Environmental Screening Report screening of the proposed Adelaide Wind Farm (the Project), In accordance with the Guide, AET is hereby notifying the to be located west of Centre Road and north and south of public that the Environmental Screening Report (ESR) / Hwy 402 in the Township of Adelaide Metcalfe, Ontario. The Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) will be available for the 30-day public review and comment period until Friday, July Project is being developed in response to the Ontario Ministry th of Energy’s desire to procure new renewable energy sources. 10 , 2009. A hard copy of the complete ESR is available for review at the following locations: Project Description AET plans to develop a wind project with a generation Adelaide Metcalfe Township Office capacity of 72 MW. The Project would involve the erection of (2340 Egremont Drive, Strathroy, ON); 40 wind turbines and installation of temporary and permanent Strathroy Public Library access roads, cabling, a substation, permanent met mast and (34 Frank Street, Strathroy, ON); and other ancillary works. Middlesex County Library Administrative Office Proponent (34B Frank Street, Strathroy, ON). AET is the North American branch of TCI Renewables and A digital copy of the report will also be available on AET’s part of the TCI Group. The company is a leading independent website at www.tcir.net renewable energy business with offices in the United Kingdom and Canada, and interests in over 30 wind power The Report is a comprehensive document that details public development projects in these countries and the United and agency consultation and findings, and describes the key States. -

The Thames River, Ontario

The Thames River, Ontario Canadian Heritage Rivers System Ten Year Monitoring Report 2000-2012 Prepared for the Canadian Heritage Rivers Board Prepared by Cathy Quinlan, Upper Thames River Conservation Authority March, 2013 ISBN 1-894329-12-0 Upper Thames River Conservation Authority 1424 Clarke Road London, Ontario N5V 5B9 Phone: 519-451-2800 Website: www.thamesriver.on.ca E-mail: [email protected] Cover Photograph: The Thames CHRS plaque at the Forks in London. C. Quinlan Photo Credits: C. Quinlan, M. Troughton, P. Donnelly Thames River, Ontario Canadian Heritage Rivers System, Ten Year Monitoring Report 2000 – 2012 Compiled by Cathy Quinlan, Upper Thames River Conservation Authority, with assistance from members of the Thames Canadian Heritage River Committee. Thanks are extended to the CHRS for the financial support to complete this ten year monitoring report. Thanks to Andrea McNeil of Parks Canada and Jenny Fay of MNR for guidance and support. Chronological Events Natural Heritage Values 2000-2012 Cultural Heritage Values Recreational Values Thames River Integrity Guidelines Executive Summary Executive Summary The Thames River nomination for inclusion in the Canadian Heritage Rivers System (CHRS) was accepted by the CHRS Board in 1997. The nomination document was produced by the Thames River Coordinating Committee, a volunteer group of individuals and agency representatives, supported by the Upper Thames River Conservation Authority (UTRCA) and Lower Thames Valley Conservation Authority (LTVCA). The Thames River and its watershed were nominated on the basis of their significant human heritage features and recreational values. Although the Thames River possesses an outstanding natural heritage which contributes to its human heritage and recreational values, CHRS integrity guidelines precluded nomination of the Thames based on natural heritage values because of the presence of impoundments. -

News Release

Phone: 519-641-1400 Fax: 519-641-1419 342 Commissioners Road, W. London, Ontario N6J 1Y3 News Release For Comment: Joe Pereira, Chair, Regional Commercial Council, 519-433-4331 For Background: Betty Dore, Chief Executive Officer, 519.641.1400 LONDON – February 1, 2016 Don Smith Commercial Building Award contenders named for 2015 The Regional Commercial Council of the London and St. Thomas Association of REALTORS® (LSTAR) has named the nineteen contenders for the 2015 Don Smith Commercial Building Awards, sponsored by CBRE, Colliers International, Dancor Construction, EllisDon Corporation, ListCentral and National Bank. Judging tour transportation generously provided by Voyageur Transportation Services. To be eligible, properties must fit into one of the following categories: Commercial (including retail and office buildings); Industrial; Institutional (community); or Multi- family. They must also be located within LSTAR’s jurisdiction of Middlesex and Elgin Counties and must have been completed between August 1, 2013 and July 31, 2015. The contenders in Commercial category are: Nixon Medical Centre (510 Southdale Road West, London ) Engineers Building ( 561-567 Talbot Street, St. Thomas) Re/Max Centre City Realty (36 First Street, St. Thomas) Rexall Pharmacy Bishop Hellmuth Heritage District (350 Oxford St. E., London) The London Roundhouse ( 240 Waterloo Street, London) a-LiNK Architecture Inc. Office ( 136 Wellington Road, London) In the Industrial category we have one nominee: Kaiser Aluminum Manufacturing Plant Expansion (3021 Gore Rd., London) Falling into the Institutional Category the nominees are: London Regional Mental Health Care- Parkwood Hospital( 550 Wellington Rd., London) The Elgin County Courthouse ( 4 Wellington St., ST. Thomas ) Elgin St. Thomas Public Health Unity (1230 Talbot St., St Thomas) Earl`s Court Village Nursing Home ( 1390 Highbury Ave. -

Appendix A-3 Part 3 Archaeological Built Heritage Reports

Appendix A-3 Part 3 Archaeological Built Heritage Reports REPORT Cultural Heritage Assessment Report Springbank Dam and "Back to the River" Schedule B Municipal Class Environmental Assessment, City of London, Ontario Submitted to: Ashley Rammeloo, M.M.Sc., P.Eng, Division Manager, Engineering Rapid Transit Implementation Office Environmental & Engineering Services City of London 300 Dufferin Avenue London, Ontario N6A 4L9 Golder Associates Ltd. 309 Exeter Road, Unit #1 London, Ontario, N6L 1C1 Canada +1 519 652 0099 1772930-5001-R01 April 24, 2019 April 24, 2019 1772930-5001-R01 Distribution List 1 e-copy: City of London 1 e-copy: Golder Associates Ltd. Project Personnel Project Director Hugh Daechsel, M.A., Principal, Senior Archaeologist Project Manager Michael Teal, M.A., Senior Archaeologist Task Manager Henry Cary, Ph.D., CAHP, RPA, Senior Cultural Heritage Specialist Research Lindsay Dales, M.A., Archaeologist Robyn Lacy, M.A., Cultural Heritage Specialist Henry Cary, Ph.D., CAHP, RPA Field Investigations Robyn Lacy, M.A. Report Production Robyn Lacy, M.A. Henry Cary, Ph.D., CAHP, RPA Elizabeth Cushing, M.Pl., Cultural Heritage Specialist Mapping & Illustrations Zachary Bush, GIS Technician Senior Review Bradley Drouin, M.A., Associate, Senior Archaeologist i April 24, 2019 1772930-5001-R01 Executive Summary The Executive Summary highlights key points from the report only; for complete information and findings, as well as the limitations, the reader should examine the complete report. Background & Study Purpose In May 2017, CH2M Hill Canada Ltd. (now Jacobs Engineering Group) retained Golder Associates Ltd. (Golder) on behalf of the Corporation of the City of London (the City), to conduct a cultural heritage overview for the One River Master Plan Environmental Assessment (EA). -

UWOMJ Volume 39, Number 2, December 1968 Western University

Western University Scholarship@Western University of Western Ontario Medical Journal Digitized Special Collections 12-1968 UWOMJ Volume 39, Number 2, December 1968 Western University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/uwomj Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Western University, "UWOMJ Volume 39, Number 2, December 1968" (1968). University of Western Ontario Medical Journal. 210. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/uwomj/210 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Special Collections at Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Western Ontario Medical Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Epilepsy ••• a baadlcap oa tile waae with THE PARKE-DAVIS FAMILY OF ANTICONVULSANTS for grand m I d for petit b1 psychomotor lzures Zarontin· Dilantin· (ethosuximide) (diphenylhydantoin sodium) ilontin· (phensuximide) ~ Dilantin witb pbe ltal (diphenylhydantoin sodium, 0.1 Gm.; for statu pilepticus phenobarbital, lfil gr.) and seizure control ~ Phelantin ., during neuro urgery (diphenylhydantoin, 0.1 Gm.; phenobarbital, lfz gr.; desoxyephedrine hydrochloride,.2.5 mg.) Dilantin Steri-Vi for psychomotor seizure (diphenylhydantoin sodium) and the petit mal triad FUU lnfonn avail a oo nquut Celontin· I PARKE-DAVIS I (meth·suximide) PAfUf.L DAVIS. C:OI'IP' ... hY. LtD. M O Nf•( .-.L, water-dispersible, hypoallergenic, pleasant-tasting OSTOCO~ROPS Children relish the flavour of multivitamin OSTOCO Drops, and welcome their administration directly on the tongue, thus ensuring the most effective absorption. OSTOCO Drops provide the vitamins which are most important to infants and young children. -

Spring-2012.Pdf

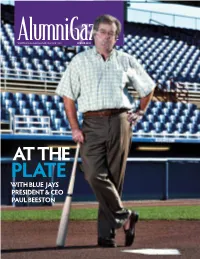

AlumniGazetteWESTERn’S ALUMNI MaGAZINE SINCE 1939 SPRING 2012 AT THE PL ATE WITH BLUE JAYS PRESIDENT & CEO PAUL BEESTON Buying?Buying? Renewing?Renewing? Refinancing?Refinancing? AlumniGazette Buying?Buying?Buying?Buying? Renewing?Renewing?Renewing?Renewing? Refinancing?Refinancing?Refinancing?Refinancing? CONTENTS ‘EVERY DAY IS SATURDAY’ 10 Cover story: At the plate with Blue Jays president & CEO Paul Beeston, BA’67, LLD’94 A DIPLOMAT FINDS HER 14 CALLING Sheila Siwela, BA’79, Zambia’s ambassador to the United States THE RIVER RUNS DEEP 16 Valiya Hamza, PhD’73, discovers underground river in Brazil THE WILL TO WIN 18 Silken Laumann, BA’89, reflects on her bronze medal win at the ’92 Olympics NEVER SaY NEVER 20 Tim Hudak, BA’90, and his path to Queen's Park 22 ROCK STAR CommittedCommitted to to Saving Saving YouYou ThousandsThousands Richard Léveillé, PhD’01, and NASA’s Mars CommittedCommittedCommitted to toto Saving SavingSaving You YouYou Thousands ThousandsThousands mission ofof Dollars Dollars on on Your Your NextNext MortgageMortgage ofofof Dollars DollarsDollars on onon Your YourYour Next NextNext Mortgage MortgageMortgage THE CIRQUE LIFE Alumni of Western University can SAVE on a mortgage 26 Craig Cohon, BA’85, brings Cirque du Soleil AlumniAlumniAlumni of of ofWestern Western Western UniversityUniversity University can can SAVE SAVE on onon a aa mortgage mortgagemortgage to Russia withAlumni the of best Western available University rates in can Canada SAVE while on a enjoyingmortgage withwithwith the the the best best best available available available ratesrates rates in in Canada Canada whilewhile while enjoying enjoyingenjoying outstandingwith the best service. available Whether rates in purchasing Canada while your enjoying first 20 outstandingoutstandingoutstanding service. -

1958 Council

LONDON FREE PRESS CHRONO. INDEX Date Photographer Description 1/1/58 B. Smith New Year's Babies at Victoria and St. Josephs Hospital Wildgust New Year's baby, St. Mary with baby boy - First New Years Baby in Chatham - Sarnia's New Year baby Wildgust Stratford...Children with tobaggans on hills K. Smith Annual mess tour K. Smith Bishop Luxton holds open house B. Smith Mr. and Mrs. C. J. Donnelly and attendants celebrate 50th wedding anniversary Blumson Barn Fire at Ingersoll 2/1/58 Blumson Officers installed at the North London Kiwanis Club at the Knotty Pine Inn J. Graham Collecting old Xmas trees J. Graham Lineup at License Bureau; Talbot Street Cantelon Wingham...First new years baby at Goderich Wildgust Stratford...New year baby to Mrs. Bruce Heinbuck Stratford K. Smith St. Peters towers go up Blumson Used Cars at London Motors Products J. Graham PUC inaugural PUC offices in City Hall 3/1/58 Burnett Snow storm Richmond at Dundas - Woodstock...Oxford farmer set up brucellosis control area J. Graham Goderich...Alexandria Marine Hospital Blumson Skiers take advantage of recent snowfall at the London Ski 1 LONDON FREE PRESS CHRONO. INDEX Date Photographer Description Club Cantelon first New Years baby Palmerston General Hospital K. Smith tobacco men meet at Mount Brydges Blumson Fred Dickson who prepares and builds violins and other string instruments Burnett London Twshp council inaugural 4/1/58 Blumson Fire at 145 Chesterfield St. J. Graham Mrs Conrons, Travellers aid at CNR Retires K. Smith Mustangs vs Bowling Green; Basketball B. Smith annual junior instruction classes at London Ski Club - fire burn Christmas tree in city dumps 5/1/58 Blumson Ice on the Thames River - Chatham...Ice fishing Mitchell's Bay J. -

Master Works Cited Archer, Michael. Art Since 1960

Master Works Cited Archer, Michael. Art Since 1960. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1997. Baker, Michael, and Hilary Bates Nealy. 100 Fascinating Londoners. Toronto: James Lorimer and Co. Ltd., 2005. Belanger, Joe. “Former Library Sold to Farhi for $2.4M.” The London Free Press, 18 May 2005. Canadian Artists Representation/Le Front des artistes canadiens (CARFAC). “CARFAC History.” CARFAC website, http://www.carfac.ca/about/history/, Accessed 13 March, 2009. ---. “What is CARFAC?” CARFAC website, http://www.carfac.ca/index-en.php, Accessed 14 March 2009. ---. “Regional Branches.” CARFAC website, http://www.carfac.ca/about/regional-branches, Accessed 13 March, 2009 ---. “What is CARFAC?.” CARFAC website, http://www.carfac.ca/about/about-carfac-a-propos-de- carfac/, Accessed 13 March, 2009 CCCA. “Artist's Curriculum Vitae.” Centre for Contemporary Canadian Art website, http://ccca.finearts.yorku.ca/cv/english/chambers-cv.html, Accessed 9 March 2009. Chambers, Jack. [1978] Jack Chambers. London, ON: [Nancy Poole]. Limited edition autobiography available in Archives and Research Collections Centre (ARCC) of The University of Western Ontario. Chandler, John Noel. “Redinger and Zelenak: A note.” artscanada, 26 no. 2 (April 1969), 23. ---. “Sources are Resources: Greg Curnoe's Objects, Objectives and Objections.” artscanada. 176, February – March 1973, 23-5. Company Histories. “Labatt Brewing Company Limited.” Company Histories, http://www.answers.com/topic/labatt-brewing-company, Accessed 20 December 2008. Colbert, Judith. London Regional Art Gallery – A Profile. London (Ont.): Volunteer Committee to the London Regional Art Gallery, 1981. Curnoe, Greg. “Five Co-op Galleries in Toronto and London from 1957 – 1992.” Unpublished notes, Greg Curnoe artist file, McIntosh Gallery, UWO, 1992. -

Attracting the World's Best

WINTER 2010 ISSUE NUMBER 13 ATTRACTING THE WORLD’S BEST illustration by Scott Woods Scott by illustration WESTERN AIMS TO HAVE 100 NEW CHAIRS WITHIN THE NEXT DECADE INSIDE | WESTERN HAS SET ITS SIGHTS ON BECOMING endowed chairs program this year. These chairs The second chair, announced in October, is the A GLOBAL LEADER IN RESEARCH WITH THE will bring new knowledge and research, Cecil and Linda Rorabeck Chair in Molecular CREATION OF UP TO EIGHT NEW ENDOWED teaching strengths, and will provide sustained Neuroscience and Vascular Biology, located in CHAIRS BY APRIL 2011 AND A TOTAL OF 100 leadership in fields of strategic importance to Western’s Schulich School of Medicine & NEW CHAIRS IN THE NEXT TEN YEARS. the University. Dentistry, Robarts Research Institute. Their gift of $1 million, along with the late Myra Millson’s During this fiscal year, the University will match The first chair established under the matching $500,000 bequest to Schulich, will see a total private gifts of $1.5 million to establish a program was announced by Western’s Richard donation of $1.5 million, to be matched by permanent $3-million endowed chair. Ivey School of Business in September, thanks to a Western to create the $3-million endowed chair. 2 gift from Ian Ihnatowycz and Marta Witer, who Schulich Dean sets sights high President Amit Chakma has laid out the directed $1.5 million of their $3.5-million gift to “When we make major donations, we often look ambitious plan, intended to help attract some of endow a Chair in Leadership. -

Proquest Dissertations

A Changing Sense of Place in Canadian Daily Newspapers: 1894-2005 By Carrie Mersereau Buchanan A.B. Bryn Mawr College M.J. Carleton University, School of Journalism and Communication A thesis submitted to The Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Journalism and Communication Faculty of Public Affairs Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario December 2009 © Carrie Mersereau Buchanan 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Voire r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-67869-5 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-67869-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduce, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nntemet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Official Programme

London Majors Labatt Park London OFFICIAL PROGRAMME 1956 ^DIAL 2-0302 AUTOGRAPHS q PLAYERS 1956 A. H. J. LUCAS FLORIST DIAL 2-7221 Special Designs For All Occasions >. > -7 Spinning Tackle 493 GROSVENOR ST.s RAYMOND BROS. LTD. LONDON Awnings - Tents PHONE 3-5756 Tarpaulins Gerry" DAVIES DUNDAS near ADELAIDE DIAL 4-3663 FRANK'S 182 YORK ST. BOYS' BASEBALL EQUIPMENT SUNOCO SERVICE LONDON Lubrication — Oil Changes Sporting Tire Repairs Goods FRANK EWANSKI, Mgr. 1194 OXFORD ST. 1195 DUNDAS ST LONDON LONDON Dairy Products 3-6861 7-8702 1411 DUNDAS ST. Montague's Refrigeration MOUNT Sealed Unit Technicians The RED BERNARD Sates and Service ROOSTER FARMS All Makes LIMITED RESTAURANT Factory Re-Finish FINE FOOD In Any Colour Progressive Co. OPEN 24 HOURS UMkmcb Gama PLAY-BY-PLAY REPORTS BY KEN ELLIS on all Saturday and Sunday Games -At Home and Away! IF ITS SPORTS NEWS -YOU HEARD IT FIRST ON <T1>I (|ial 980 COMPLETE BASEBALL RESULTS - 7:05 a.m - 8:05 a.m., 6:15 p.m., 11:20 p.m. DAILY! Lou Ball REACH FOR . Extends his Compliments and Best Wishes Parnell's LOU BALL CLOTHES LTD. Ready Made and Tailored Suits Men's Furnishings BUTTER-NUT Corner DUNDAS & TALBOT - LONDON ROCKY'S CYCLE Bread CENTRE ALWAYS FRESH - ALWAYS TASTY C.C.M. BICYCLES and TRICYCLES HARLEY-DAVIDSON MOTORCYCLES — Serving Londoners For 85 Years — Repairs to All Makes Wharncliffe & Emery Phone 3-7015 The London Baseball Club INTER-COUNTY LEAGUE LEN MocDONALD JACK COLEMAN FRANK COLEMAN Promotion Mgr. Vice-President President FRED (Slim) GORMAN POTTER & SON YOUR CARPETS CITIES SERVICE DEALER 1409 Dundas Street London, Ont. -

Economic Development Committee Meeting Agenda Tuesday, September 9, 2014 at 7 Pm 1. Call to Order 2. Acceptance of Agenda (Motio

Economic Development Committee Meeting Agenda Tuesday, September 9, 2014 at 7 pm 1. Call to Order 2. Acceptance of Agenda (motion to accept) 3. Declaration of Pecuniary Interest 4. Delegation - Karisa Downey, Business Development Coordinator, LaunchIt Minto 5. Business Arising 6. New Business - Maitland Mill - MVCA future plans - 2nd Annual Huron Career Fair - Destination Downtown Conference Sept 15 - County of Huron Annual Tourism Report - welcome to Howick signs (Strategic Plan) 7. Closed Session - personal matters about an identifiable individual (one letter of interest received to sit on Howick Economic Development Committee) 8. Adjournment PO Box 89 44816 Harriston Rd. Gorrie, ON N0G 1X0 Tuesday August 26, 2014 Dear Howick Economic Development Committee, As part of the Town of Minto’s economic development strategy, the Town, in partnership with the Minto Chamber of Commerce have developed a Creative Industry Business Incubator called LaunchIt Minto. LaunchIt Minto strives to assist new businesses to start, grow and succeed in a creative environment. LaunchIt Minto was developed to fulfill a void in the lack of training programs and business services offered in Northern Wellington and the surrounding rural areas. LaunchIt Minto has developed a Business Excellence Program consisting of training, mentorship, coaching and networking programs. These programs are designed to educate new and established business owners on a wide range of business strategies and help develop invaluable connections with other local business owners in the area. Business owners are able to purchase a Business Excellence Program monthly membership which includes the training, mentorship, coaching and networking, or pay per training and networking session. In order to facilitate these programs, LaunchIt Minto has formed relationships with Innovation Guelph, Guelph Wellington Business Enterprise Centre, Waterloo Wellington Community Futures Development Corporation and Saugeen Economic Development Corporation.