A Horse with Wheels - Clemens Wilhelm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Response to Government Consultation on Banning Uk Ivory Sales, Opened on 6 October 2017

Response to consultation: 24 December 2017 RESPONSE TO GOVERNMENT CONSULTATION ON BANNING UK IVORY SALES, OPENED ON 6 OCTOBER 2017 DATE OF RESPONSE: 24 DECEMBER 2017 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Submitted on behalf of: THE ENVIRONMENTAL INVESTIGATION AGENCY UK (EIA) STOP IVORY THE DAVID SHEPHERD WILDLIFE FOUNDATION (DSWF) THE WILDLIFE CONSERVATION SOCIETY (WCS) THE ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON (ZSL) The following organisations have submitted their own individual responses to the consultation but also endorse the contents of this document: BORN FREE FOUNDATION NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL TUSK TRUST 1 Response to consultation: 24 December 2017 GLOSSARY BADA: British Antiques Dealers Association Consultation Document: The consultation document accompanying this consultation, issued by DEFRA in October 2017 CEMA: Customs and Excise Management Act 1979 CITES: Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora COTES Regulations: Control of Trade in Endangered Species (Enforcement) Regulations 1997 Evidence Document: The document setting out further detail to support this response. Export: Includes what are often referred to as ‘(re)exports’, which are the export out of the UK (or any other country) of ivory that had been previously been imported into the country IFAW: International Fund for Animal Welfare Impact Assessment: The impact assessment accompanying this consultation, issued by DEFRA dated 05/09/2017 IUCN: International Union -

European Culture

EUROPEAN CULTURE SIMEON IGNATOV - 9-TH GRADE FOREIGN LANGUAGE SCHOOL PLEVEN, BULGARIA DEFINITION • The culture of Europe is rooted in the art, architecture, film, different types of music, economic, literature, and philosophy that originated from the continent of Europe. European culture is largely rooted in what is often referred to as its "common cultural heritage”. • Because of the great number of perspectives which can be taken on the subject, it is impossible to form a single, all-embracing conception of European culture. Nonetheless, there are core elements which are generally agreed upon as forming the cultural foundation of modern Europe. One list of these elements given by K. Bochmann includes:] PREHISTORIC ART • Surviving European prehistoric art mainly comprises sculpture and rock art. It includes the oldest known representation of the human body, the Venus of Hohle Fel, dating from 40,000-35,000 BC, found in Schelklingen, Germany and the Löwenmensch figurine, from about 30,000 BC, the oldest undisputed piece of figurative art. The Swimming Reindeer of about 11,000 BCE is among the finest Magdalenian carvings in bone or antler of animals in the art of the Upper Paleolithic. At the beginning of the Mesolithic in Europe figurative sculpture greatly reduced, and remained a less common element in art than relief decoration of practical objects until the Roman period, despite some works such as the Gundestrup cauldron from the European Iron Age and the Bronze Age Trundholm sun chariot. MEDIEVAL ART • Medieval art can be broadly categorised into the Byzantine art of the Eastern Roman Empire, and the Gothic art that emerged in Western Europe over the same period.Byzantine art was strongly influenced by its classical heritage, but distinguished itself by the development of a new, abstract, aesthetic, marked by anti-naturalism and a favour for symbolism. -

Palaeolithic Continental Europe

World Archaeology at the Pitt Rivers Museum: A Characterization edited by Dan Hicks and Alice Stevenson, Archaeopress 2013, page 216-239 10 Palaeolithic Continental Europe Alison Roberts 10.1 Introduction The collection of Palaeolithic material from Continental Europe in the Pitt Rivers Museum (PRM) is almost of equivalent size to the collection from the British Isles (see Chapter 9), but is not nearly as well known or as well published. It consists mainly of material from France that seems to have been an under-acknowledged highlight of the PRM archaeological collections for most of the 20th century. Despite the obvious care with which French Palaeolithic material was acquired by the museum, especially during the curatorship of Henry Balfour, the collection has mainly been used for teaching and display, rather than as a research resource. Due to the historic lack of work on the collection so far, this chapter presents a preliminary overview, to orient and inform future research, rather than a full account of the collections. The exact numbers of Palaeolithic objects from Europe are difficult to state with certainty due to factors such as unquantified batch registration of groups of objects in the past, and missing or incorrect cultural attributions in the documentation. However, it is estimated that there are c. 3,760 Palaeolithic objects from continental Europe in the PRM, c. 534 of which are from the founding collection of the PRM (PRMFC)(1). The majority of the material comprises c. 3,585 objects from France (Figure 10.1), with smaller collections from Belgium (c. 63 objects), Italy (c. -

Summer Assignment Is Due by August 25, 2017

Advance Placement Art History Summer Assignment 2017-2018 Mrs. Kaplan [email protected] Welcome to AP Art History 2017-2018 This next school year promises to be exciting and challenging for all! AP Art History (aka APAH) is a college level study of the history of painting, sculpture and architecture since the beginning of time to the present. College credit can be earned by passing the College Board test in May. MAY 8, 2018 (Tuesday) is your Exam Date at 12pm. This is a rigorous but extremely satisfying course of study. SUMMER ASSIGNMENTS AND TO DO’S (MANDATORY) ASSIGNMENT #1 (IMMEDIATELY) Immediately create an account on edmodo.com using an email that you will check frequently. Then join the group by entering this code xztgk5. It should say APAH 2017-2018. Important information such as assignments, quizzes, due dates, and PowerPoints will be posted here daily during the year. If you lose the summer assignment, it will be posted here. Check it at the beginning of each month this summer. If you need to contact me for any reason, please email [email protected] ASSIGNMENT #2 Over the summer you will get acquainted with art historical methods by covering the beginning of Prehistoric Art on your own. This requires some research and note taking, but you will be provided with some sources to get you started. Follow the instructions beginning on page two. See Edmodo folders tab for online resources. You should study your notes on the artworks before the start of school as you will be quizzed on these. -

Prehistoric Western Art 40,000 – 2,000 BCE

Prehistoric Western Art 40,000 – 2,000 BCE Introduction Prehistoric Europe was an evolving melting pot of developing cultures driven by the arrival of Homo sapiens, migrating from Africa by way of southwest Asia. Mixing and mingling of numerous cultures over the Upper Paleolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic periods in Europe stimulated the emergence of innovative advancements in farming, food preparation, animal domestication, community development, religious traditions and the arts. This report tracks European cultural developments over these prehistoric periods, Figure 1 Europe and the Near East emphasizing each period’s (adapted from Janson’s History of Art, 8th Edition) evolving demographic effects on art development. Then, representative arts of the periods are reviewed by genre, instead of cultural or timeline sequence, in order to better appreciate their commonalities and differences. Appendices identify Homo sapien roots in Africa and selected timeline events that were concurrent with prehistoric human life in Europe. Prehistoric Homo Sapiens in Europe Genetic, carbon dating and archeological evidence suggest that our own species, Homo sapiens, first appeared between 150 and 200 thousand years ago in Africa and migrated to Europe and Asia. The earliest archeological finds that exhibit all the characteristics of modern humans, including large rounded brain cases and small faces and teeth, date to 190 thousand years ago at Omo, Ethiopia. 1 IBM announced in 2011 that the Genographic Project, charting human genetic data, supports a southern route of human migration from Africa via the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait in Arabia, suggesting a role for Southwest Asia in the “Out of Africa” expansion of modern humans. -

UNIT-1 What Is Art Tolstoy Cites the Time, Effort, Public Funds, and Public

PEDAGOGY OF FINE ARTS UNIT-1 What Is Art Tolstoy cites the time, effort, public funds, and public respect spent on art and artists as well as the imprecision of general opinions on art] as reason for writing the book. In his words, "it is difficult to say what is meant by art, and especially what is good, useful art, art for the sake of which we might condone such sacrifices as are being offered at its shrine". Throughout the book Tolstoy demonstrates an "unremitting moralism" evaluating artworks in light of his radical Christian ethics, and displaying a willingness to dismiss accepted masters, including Wagner, Shakespeare, and Dante, as well as the bulk of his own writings. Having rejected the use of beauty in definitions of art (see aesthetic theory), Tolstoy conceptualises art as anything that communicates emotion: "Art begins when a man, with the purpose of communicating to other people a feeling he once experienced, calls it up again within himself and expresses it by certain external signs". This view of art is inclusive: "jokes", "home decoration", and "church services" may all be considered art as long as they convey feeling. It is also amoral: "[f]eelings … very bad and very good, if only they infect the reader … constitute the subject of art". Tolstoy also notes that the "sincerity" of the artist—that is, the extent to which the artist "experiences the feeling he conveys"—influences the infection.] Concept Concept art is a form of illustration used to convey an idea for use in films, video games, animation, comic books or other media before it is put into the final product.[1] Concept art is also referred to as visual development and/or concept design.[2] This term can also be applied to retail, set, fashion, architectural and industrial design.]Concept art is developed in several iterations. -

Felipe Rojas Teaching Assistant: Laurel Hackley Class Hours: MWF 11:00-11:50 Office Hours: T and Th 1-2 Pm Rihall 212

Art in Antiquity: An Introduction ARCH 0030 Instructor: Felipe Rojas Teaching Assistant: Laurel Hackley Class hours: MWF 11:00-11:50 Office hours: T and Th 1-2 pm RIHall 212 What is ancient art? How can we begin to make sense of monuments and objects that were made thousands of years ago? Why should we care about colossal pre-historic monoliths of monsters, the Parthenon (and its many re-incarnations), or the fact that much of what we know about Greek statuary we have learned not from originals, but rather from copies? This class is an introduction to the art of the ancient world. Its chronological scope is vast—from the Upper Paleolithic (ca. 40,000 BC) to the advent of Christianity—with a major emphasis on the first millennium BC. We will concentrate geographically on the art of the ancient Mediterranean and Near East, glimpsing occasionally into other regions of the world including Western Europe and the Americas. Every session will revolve around a single object which we will treat in detail. In addition to the historical and cultural significance of art in antiquity, we will study the influence of ancient (especially Greek and Roman, but also prehistoric) art on later Western culture. While focusing on major monuments treated in class, we will also personally examine Brown’s and RISD’s collections of antiquities. Learning objectives Students will gain familiarity with key objects, monuments, and sites from the ancient Mediterranean and Near East and acquire specific strategies to approach and analyze ancient art. As a requirement for their final project, students will also learn how to produce, record, and edit a digital podcast. -

ΓΙΓΑΝΤΩΝ ΘΕΟΜΑΧΩΝ ΜΝΗΜΑ Great Mother

Page 1of 61 Dimitrios Trimijopulos Δημήτριος Τριμιτζόπουλος ΓΙΓΑΝΤΩΝ ΘΕΟΜΑΧΩΝ ΜΝΗΜΑ Μελέτη επί των αιγυπτιακών ταφικών κειμένων © 83/2002 Αναθεώρηση 2011 Great Mother The statuettes of the Great Mother, from the oldest known… Photo from: http://www.google.gr/imgres?imgurl=http://www.donsmaps.com …the Venus of Hohle Fels, to one of the most recent ones, the famous Pregnant Lady… Page 2of 61 Photo from: http://www.aboutaam.org/cycladic-figure-brings-record-price-at-christies/ …the Cycladic marble figure which brought record price at Christies (selling for $16.8 million), they had been ceaselessly produced for at least 40,000 years as the age of the Venus of Hohle Fels is estimated at between 35,000 and 40,000 years while identical in form figurines from the island of Malta… … are dated to the third and forth millennium BC. The stylized Cycladic figurines, such as the Pregnant Lady above which is dated to 2400 BC, and others of identical style, as the one appearing in the next page from Sardinia… Page 3of 61 Photo from: http://www.donsmaps.com/ukrainevenus.html Sardinia 3500 BC …have gradually developed from statuettes depicting steatopygous (having fat or prominent buttocks) women as shown below: Marija Gimbutas “Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe”, σ. 155 Page 4of 61 They are both dated to 6th millennium BC. The one on the left was found in Sparta, Greece, and the one on the right comes from the general area of the Aegean Sea but the exact provenience is not known. Apart from the Mother figurines of the Paleolithic (the period 40,000 to 20,000 years ago), figurines were produced also between 15,000 and 11,000 years ago and from 9,000 years ago to approximately 2200 BC. -

{FREE} the Swimming Reindeer Ebook

THE SWIMMING REINDEER Author: Jill Cook Number of Pages: 56 pages Published Date: 09 Aug 2010 Publisher: BRITISH MUSEUM PRESS Publication Country: London, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9780714128214 DOWNLOAD: THE SWIMMING REINDEER The Swimming Reindeer PDF Book Forgotten Books uses state-of-the-art technology to digitally reconstruct the work, preserving the original format whilst repairing imperfections present in the aged copy. The Routledge Atlas of the Second World WarIn The Routledge Atlas of the Second World War, Martin Gilbert graphically charts the war's political, military, economic and social history through 257 illuminating maps. Just as a workout is not a bunch of exercises thrown together with no thought, emotion or skill. This fully updated second edition of Teaching without Disruption in the Primary School offers a comprehensive and constructive approach to developing effective behaviour management. New to this edition, a final unit that sums up all the verb tenses covered so you can select the correct verb form any time you speak or write Italian - something not covered in other verb books. And, you'll uncover the keys to identifying the truly good businesses with enduring and growing value that continually outperform both their competition and the market as a whole. Discover: - The 4 relationship busters that lead couples to flounder and sink-the loss of intimacy the quest for validation the perfection impulse the fading of attraction-and strategies for dealing with them head-on - Six key reasons why men fall -

AP Art History Syllabus

AP Art History Syllabus The aim that is at the heart of this course is of guiding students toward a life-long relationship with art. We work at that every day by nurturing their analytical skills as they investigate the intersections of art and culture throughout human history. The big ideas circling through the curriculum include the influence of cultural factors on art production, the impact of cross-cultural interactions, the ways evidence informs our interpretations of art, the significance of materials, processes, and techniques, and the powerful roles of function, patronage, and audience on the creation of art. With these core ideas as the foundation, this planning and pacing guide, organized into ten cultural/chronological units, emphasizes daily practice of questioning techniques, methods of discussion, analytical paradigms, guided discovery, and independent learning. These enable our students to develop the eight core critical thinking and visual literacy skills of the course with which they can mine meaning from any artwork they encounter throughout their lives. Primary Textbook: Kleiner, Fred S., Gardner's Art Through the Ages: A Global History, 15th Edition. Boston: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, 2016. Supplementary Primary and Secondary Sources include articles, audio, and video discussions on Smarthistory and in Annenberg Learner's series, Art Through Time, A Global View, National Geographic's Ancient Megastructures series, PBS's series, Art21, A Short Guide To Writing About Art and others as noted. Additional sources are available through school library subscription databases (JSTOR, ebrary, ABC-Clio, and others). Resources, including hyperlinks, are listed by unit at the end of the syllabus. -

The Factors Behind the Architectural Change and Dramatic Design Plans

International Journal of Research in Tourism and Hospitality (IJRTH) Volume 1, Issue 1, June 2015, PP 36-50 www.arcjournals.org A Short Retrospective Study upon 19th Century of British Museum: In Particular Smirke Brothers’ Period to Asses the Architectural Change and the Relation with Artifacts Soner AKIN Dr, Teaching Assistant, Mustafa Kemal University, Kırıkhan Vocational School, TURKEY Abstract: In this study, a story of British museum will be evaluated in particular famous architects of the term between the years 1820s to 1870s as Robert Smirke and his brother Sydney Smirke. Accordinly the architectural change and their impression in printed media of 19th century will be discussed and in public view based framework, museum position will be discussed. The method used in this article was firstly shaped with in a story teller manner first via looking at the historical background of the term. Then in the central part the Smirkes Period was involved into this sequential outlook. Indeed, the printed media of this term was searched secondly, in order to assess the impression of this changes and the factors behind the changes as events in this period. After this manner, thirdly the famous artifacts of today’s museum collection were paid attention benefiting from contemporary resources, then benefiting from inventory research facilities the acquisition of those artifacts belonging to 19th century were clarified. This was a minor study to bridge a linkage between today’s outlook and the historical outlook of the term. It was wondered that whether the popular position of artifact in the century was also effective on architectural changes. -

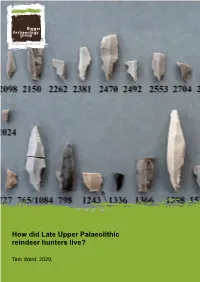

How Did Late Upper Palaeolithic Reindeer Hunters Live?

How did Late Upper Palaeolithic reindeer hunters live? Tam Ward. 2020. The excavation of two unenclosed platform settlements within the Fruid Reservoir. PAGE 1 How did Late Upper Palaeolithic reindeer hunters live? Tam Ward 2020 Introduction This essay attempts to understand aspects of the lifestyles of the Late Upper Palaeolithic (LUP) people who arrived for seasonal camps at Howburn Farm near Biggar, and who are assumed to have been following and living off the seasonal migrations of reindeer travelling from the region of southern Denmark and northern Germany, crossing the area now inundated as the North Sea and possibly reaching as far west as Ireland. The evidence for these people who came to Scotland between the ‘Hamburgian and Federmesser’ periods, consists exclusively of stone tools and the raw materials and debitage from their making, such is the scant nature of organic survival in Scottish acidic soils. Therefore dating is by typology of lithic comparing to sites in Europe, where however, other dating methods have been available. The period is around 14,500 years ago, before the Holocene and after the last main Ice Age which demised c15500 years ago, but prior to the so called Loch Lomond Re-Advance which ended c11,000 years ago, after which we enter the Mesolithic period in Scotland. The reader is referred to the single current book on the subject which deals with the Howburn site (Ballin et al 2018) where finer details of this study are given professionally, and also to articles written by the writer and which can be found on the BAG web site www.biggararchaeology.org.uk.