Existentialism / Biography / Being in the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2021 Seasonal Catalog

Princeton University Press 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540-5237 Princeton University Press fall 2021 fall 2021 Cover image: Cubism—Landsat Style: startling red patches sprout from an agricultural landscape that looks almost like a Cubist painting. The fields in this part of eastern Kazakhstan follow the contours of the land—long and narrow in mountain valleys, and large and rectangular over the plains. Landsat imagery courtesy of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and U.S. Geological Survey. Contents 1 Trade 55 Zone Books 58 Nature 76 Art & Architecture 89 Academic Trade 117 Paperbacks 148 Classics 148 History 151 Political Science 154 Social Science 157 Literature 160 Philosophy 161 Economics 161 Anthropology 162 Neuroscience 163 Biology 165 Geophysics 165 Physics 167 Computer Science 167 Mathematics 169 Audiobooks 170 Subrights Information 171 Best of the Backlist 176 Index 178 Order Information Trade 2 Trade Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the Modern Mary Beard From the bestselling author of SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome, the fascinating story of how images of Roman autocrats have influenced art, culture, and the representation of power for more than 2,000 years What does the face of power look like? Who gets a simple repetition of stable, blandly conservative commemorated in art and why? And how do we react images of imperial men and women, Twelve Caesars is to statues of politicians we deplore? In this book Mary an unexpected tale of changing identities, clueless or Beard tells the story of how portraits of the rich, deliberate misidentifications, fakes, and often ambiva- powerful, and famous in the western world have been lent representations of authority. -

PHIL3009 TOPICS in EUROPEAN PHILOSOPHY Fall 2016 PROFESSOR GERALDINE FINN PA3A61 EXT 1783

PHIL3009 TOPICS IN EUROPEAN PHILOSOPHY Fall 2016 PROFESSOR GERALDINE FINN PA3A61 EXT 1783 DESCRIPTION This course introduces students to phenomenology and existential philosophy through close readings of selected writings from some of its most influential thinkers. The course will be run as a seminar with individual students assuming responsibility for the introduction of the assigned readings each week. Assessment will be based on seminar presentation and participation and final take-home exam. REQUIRED TEXTS ordered and available from AllBooks 327 Rideau St. next to the Bytowne Cinema (# 7 bus takes you right there). Open 10.00 am – 9.00 pm Mon-Sat, Noon – 9.00 pm Sun. Tel 613 789 9544): 1. At the Existentialist Café. Freedom, Being and Apricot Cocktails by Sarah Bakewell. Chatto and Windus, 2016. 2. Sketch for a Theory of the Emotions by Jean-Paul Sartre (orig. 1939). 3. The Ethics of Ambiguity by Simone de Beauvoir (orig. 1944). OTHER REQUIRED READINGS are available on RSV at the library and include the following: 1. ‘Intentionality: A Fundamental Idea of Husserl’s Phenomenology’ by Jean-Paul Sartre (1939) from The Phenomenology Reader, edited by Dermont Moran and Timothy Mooney (London, Routledge, 2002). Also available on line in Thomas Sheehan’s notes for his Sartre course at Stanford University. 2. ‘The Question Concerning Technology’ by Martin Heidegger (1949/53) from Martin Heideger. Basic Writings edited by David Farrell Krell (Harper and Row, orig.1977). 3. ‘Throwing Like a Girl. A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment, Motility, and Spatiality’ by Iris Marion Young (1977) from The The Thinking Muse. -

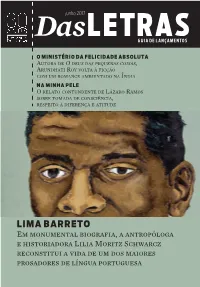

Lima Barreto

junho 2017 DasLETRASGUIA DE LANÇAMENTOS O MINISTÉRIO DA FELICIDADE ABSOLUTA AutorA de o deus dAs pequenAs coisAs, ArundhAti roy voltA à ficção com um romAnce AmbientAdo nA ÍndiA NA MINHA PELE o relAto contundente de lázAro rAmos sobre tomAdA de consciênciA, respeito à diferençA e Atitude LIMA BARRETO Em monumental biografia, a antropóloga e historiadora Lilia Moritz Schwarcz reconstitui a vida de um dos maiores prosadores de língua portuguesa Sumário dos lançamentos 3 NO CAFÉ EXISTENCIALISTA 11 OUTRA 20 ANNA KARIÊNINA sArAh bAkewell SINTONIA liev tolstói 4 NA MINHA PELE John donvAn & 22 BORGES cAren zucker lázAro rAmos BABILÔNICO Jorge schwArtz (org.) 12 MAIS DE UMA LUZ Amós oz 6 GETÚLIO 23 O MARTÍN FIERRO, VARGAS, MEU PARA AS SEIS PAI CORDAS & EVARISTO AlzirA vArgAs CARRIEGO do AmArAl Jorge luis borges peixoto 13 A GUERRA DO FIM DOS TEMPOS grAeme wood 7 JUROS, MOEDA E 24 INVENÇÃO DE ORTODOXIA ORFEU André lArA Jorge de limA resende 14 LIMA BARRETO liliA moritz schwArcz 8 CAMINHOS DA 25 FACA E ESQUERDA LIVRO DOS ruy fAusto HOMENS ronAldo correiA AS CABEÇAS 16 de brito TROCADAS thomAs mAnn 9 PARA 26 OS MISERÁVEIS ENTENDER UMA victor hugo FOTOGRAFIA John berger 17 A FAMÍLIA MANZONI nAtAliA ginzburg 10 ALGORITMOS 27 SOBRE A BREVIDADE DA VIDA/ PARA VIVER SOBRE A FIRMEZA DO SÁBIO briAn christiAn sênecA & tom griffiths 18 O MINISTÉRIO DA FELICIDADE ABSOLUTA 28 O ÚLTIMO GRITO ArundhAti roy thomAs pynchon EDITORA SCHWARCZ S.A. RUA BANDEIRA PAULISTA, 702, CJ. 32 CEP 04532-002 – SÃO PAULO – SP – BRASIL TELEFONE: (11) 3707-3500 facebook.com/companhiadasletras -

Sarah Bakewell Das Café Der Existenzialisten Freiheit, Sein Und Aprikosencocktails

Unverkäufliche Leseprobe Sarah Bakewell Das Café der Existenzialisten Freiheit, Sein und Aprikosencocktails 448 Seiten mit 26 Abbildungen. Gebunden ISBN: 978-3-406-69764-7 Weitere Informationen finden Sie hier: http://www.chbeck.de/16551096 © Verlag C.H.Beck oHG, München INHALT DES BUCHES Erstes Kapitel: Monsieur, wie schrecklich, Existenzialismus! 13 in dem drei Freunde Aprikosencocktails trinken, einige Leute bis spät nachts über Freiheit diskutieren und noch mehr ihr Leben ändern. Außerdem fragen wir, was Existenzialismus ist. Zweites Kapitel: Zu den Sachen selbst 51 in dem wir die Phänomenologen kennenlernen Drittes Kapitel: Der Zauberer von Meßkirch 67 in dem Martin Heidegger auftritt und das Sein uns in Verlegenheit bringt Viertes Kapitel: Das «Man», der Ruf 91 in dem Sartre Albträume hat und Heidegger zu denken versucht, Karl Jaspers bestürzt ist und Husserl zu Heroismus aufruft Fünftes Kapitel: Blühende Mandelbäume abweiden 119 in dem Jean-Paul Sartre einen Baum beschreibt, Simone de Beauvoir Ideen zum Leben erweckt und wir Maurice Merleau-Ponty und der Bourgeoisie begegnen Sechstes Kapitel: Ich möchte nicht, dass man mich zwingt, meine Manuskripte zu fressen 143 in dem es zu einer Krise kommt, zu zwei heroischen Rettungsaktionen und zu einem neuen Krieg Siebtes Kapitel: Okkupation und Befreiung 161 in dem der Krieg weitergeht, wir Albert Camus kennenlernen, Sartre die Freiheit entdeckt, Frankreich befreit wird, die Philosophen sich engagieren und alle nach Amerika wollen Achtes Kapitel: Verwüstung 203 in dem Heidegger eine Kehrtwende -

Summer Reading - Philosophy

Summer Reading - Philosophy If you about to embark on your philosophical journey and want to do some preparatory reading beforehand, we suggest two types of book that would be useful for you to read. One or two of each type is sufficient. Although some preparation is undoubtedly helpful, don’t feel that you have to prepare intensively or exhaustively. The two types of book are, 1). an introduction to the history of ideas, and 2). a topic-based introduction. The first will give you a chronological overview of the development of thought, which is useful because later thinkers, in their various traditions, are in conversation with earlier ones and this will help you orientate yourself in those conversations. The second will allow you to engage with particular philosophical problems and arguments more directly and encourage you to think about them for yourself, without necessarily being encumbered by the weight of tradition. In each category, we suggest: Introductions to the History of Ideas David Cooper, World Philosophies: An Historical Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell, 2002, 2nd edition. (Written by a philosopher who is happy working across different thought traditions, this looks at the history of ideas from a global perspective.) Anthony Kenny, A New Introduction to Western Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. (A comprehensive survey of the key ideas in European thought by one of Britain’s most eminent philosophers. Kenny has also written other introductions that focus on particular historical periods.) Bertrand Russell, History of Western Philosophy. London: Routledge, 2004. (First published in 1945, this is a classic example of the genre—even though it obviously leaves out important developments in the second half of the twentieth century. -

At the Existentialist Cafe: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails Free

FREEAT THE EXISTENTIALIST CAFE: FREEDOM, BEING, AND APRICOT COCKTAILS EBOOK Sarah Bakewell,Antonia Beamish | none | 25 Oct 2016 | Audible Studios on Brilliance | 9781536617474 | English | United States At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails by Sarah Bakewell – review Paris, Three contemporaries meet over apricot cocktails at the Bec-de-Gaz bar on the rue Montparnasse. They are the young Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and longtime friend Raymond Aron, a fellow philosopher who raves to them about a new conceptual framework from Berlin called phenomenology. At the Existentialist Cafe: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails is a book written by Sarah Bakewell that covers the philosophy and history of the 20th century movement existentialism. The book provides a very accurate account of the modern day existentialists who came into their own before and during the second world war. The book discusses the ideas of the phenomenologist Edmund Husserl, and how his teaching influenced the rise of existentialism through the likes of Martin Heidegger, Jea. Paris, Three contemporaries meet over apricot cocktails at the Bec-de-Gaz bar on the rue Montparnasse-- and ignite a movement, creating an entirely new philosophical approach inspired by themes of radical freedom, authentic being, and political activism: Existentialism. Interweaving biography. and philosophy, Bakewell provides an investigation into what the existentialists have to offer us today, at a moment when we are once again confronting the major questions of freedom, global. At the Existentialist Café Paris, Three contemporaries meet over apricot cocktails at the Bec-de-Gaz bar on the rue Montparnasse. They are the young Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and longtime friend Raymond Aron, a fellow philosopher who raves to them about a new conceptual framework from Berlin called phenomenology. -

The Making of the Modern Self

Final Syllabus The Making of the Modern Self: Existential Philosophy University of Copenhagen Department of Theology / DIS Spring Semester 2017 3 credits Major Disciplines: Literature, Philosophy, Ethics Class Meetings: Thursdays 12:00-14:30. University of Copenhagen, South Campus, Room 6B.0.22 Course Instructors: Anna Strelis Söderquist Brian Söderquist DIS Contacts: Matt Kelley, Program Assistant, European Humanities Department Computer policy: No computers in class. No net, no texting during class. Course Content: Focusing on thinkers from the Existentialist tradition such as Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Copenhagen’s own Søren Kierkegaard, this course traces the development of the conception of “selfhood.” Among other things, we will observe how ethical thinking has moved from the language of duty to that of personal answerability, and how the search for meaningful personal existence has increasingly become the responsibility of the individual. The unique vocabulary of these authors appears not only in works of philosophy, theology, and psychology, but also literature and theatre, which illustrates that we understand ourselves via the stories we tell, and that these narratives are necessarily told in dialogue with “the Other,” our fellow human beings. Readings: Completion of reading assignments as scheduled is required and is a prerequisite for participating in class discussions. Lectures and Discussion: In general, class will be a combination of lecture and class discussion. Class participation includes attendance and contributions students make in class. Small Papers: Three small papers (4-5 double-spaced pages) will be assigned during the course of the semester. Late papers will be penalized a half-grade for each day after the due date. -

Bakewell, Sarah. at the Existentialist Café, Chatto & Windus, London

http://dx.doi.org/10.12775/szhf.2017.035 Bakewell, Sarah. At the Existentialist Café, Chatto & Windus, London, 2016, pp. 440 When we start to discuss existentialism, it is probably impossible to avoid the question of whether existentialism is over or not. I have heard this query since the moment I started to be interested in philosophy, which was almost half a century ago. Recently, I have heard it at a student conference dedicated to existentialism. The conference took place several months ago in Gniezno and was attended by over sixty participants. At that point, I asked: “If existen- tialism is over, what are you doing here, ladies and gentlemen?” With this very question about the end of existentialism, Sarah Bakewell begins and also ends her today’s popularity record-breaking bestseller At the Existentialist Café (the next bestseller of this well-known populariser of phi- losophy). On the third page of the core text in the book, how could it not, we find the photographs of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir sit- ting at a café table. After all, existentialism is “a café philosophical belief”. I heard that “café existentialists” really existed, also in our country, as early as in the seventies; however, the truth is that in Poland, there has never been any true existentialist in the sense in which Roman Ingarden and his nu- merous followers were at that time and still are phenomenologists. And the availability of coffee in the forties in the PRL (the Polish People’s Republic) was problematic as well. Nevertheless, we could always meet young sensitive people dressed in black sweaters, fascinated by the fundamental questions in the field of human philosophy. -

Read Book at the Existentialist Cafe: Freedom, Being, and Apricot

AT THE EXISTENTIALIST CAFE: FREEDOM, BEING, AND APRICOT COCKTAILS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sarah Bakewell | 448 pages | 01 Apr 2016 | Vintage Publishing | 9780701186586 | English | London, United Kingdom At the Existentialist Cafe: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails PDF Book Even non-human animals mostly follow the instincts and behaviours that characterise their species, Sartre believed. No library descriptions found. Bakewell serves up information in steps, from early phenomenological thinkers up to ones that broke off with a lot of the early ones, also putting some history behind things. How did she do it? Of course I may be influenced by my biology, or by aspects of my culture and personal background, but none of this adds up to a complete blueprint for producing me. So, what's this book about? I have always admired existentialism and some of the literary works of Sartre chiefly his short story, "The Wall" and Camus chiefly his novel, The Stranger. Some have come out alive but at a terrible cost. For Jane and Ray. Three contemporaries meet over apricot cocktails at the Bec-de-Gaz bar on the rue Montparnasse-- and ignite a movement, creating an entirely new philosophical approach inspired by themes of radical freedom, authentic being, and political activism: Existentialism. But he was grumpy and Sartre never stopped talking. Collaborative Review. But The Outsider was also thrilling. Project Gutenberg 0 editions. Simone de Beauvoir - Leading French existentialist philosopher, novelist, feminist, playwright, essayist and political activist. The word was first used in prewar Germany to describe the kind of philosophy, propounded by Martin Heidegger and Edmund Husserl, that argued existence in itself was meaningless and morality was a fiction. -

The English Dane: from King of Iceland to Tasmanian Convict Free

FREE THE ENGLISH DANE: FROM KING OF ICELAND TO TASMANIAN CONVICT PDF Sarah Bakewell | 352 pages | 02 Mar 2006 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099438069 | English | London, United Kingdom Jørgen Jørgensen - Wikipedia Sarah Bakewell has a fine story to tell, and she is its skilled servant. It is the story of Jorgen Jorgenson, an extraordinary Georgian figure who would have been invented by some novelist had he not in fact existed. As soon as you have said he is a revolutionary you must also say he was an anti-Napoleonic Anglophile. As soon as you say he was an enthusiast you must entertain the possibility that he was, to quote Bakewell, "Toad of Toad Hall", and as soon as you say he was one of the founders of Van Diemen's Land and grand protector of Iceland, you have also to mention that he was a British convict. Jorgenson is remembered both as king of Iceland for one heady summer at one end of the globe, and the Viking of Van Diemen's Land at the other, and to an extent he seems a being created by the Earth's zapping north-south electric field. When the Prince of Denmark recently wedded his Tasmanian Van Diemen's Land wife, he declared he followed in the earlier Dane, Jorgenson's, footsteps with just as much hope and just as much confidence. The prince did not mention Jorgenson's endlessly zealous, inventive and disordered brilliance. The son of the clockmaker to the Danish king, Jorgenson was not a creature of orderly cogs but of lightning, born ina year on the cusp The English Dane: From King of Iceland to Tasmanian Convict turbulence. -

Unverkäufliche Leseprobe Sarah Bakewell Das Café Der

Unverkäufliche Leseprobe Sarah Bakewell Das Café der Existenzialisten Freiheit, Sein und Aprikosencocktails 2018. 448 S., mit 26 Abbildungen. Broschiert. ISBN 978-3-406-72479-4 Weitere Informationen finden Sie hier: https://www.chbeck.de/4588 © Verlag C.H.Beck oHG, München Paris 1932, im Café Bec-de-Gaz sagt Raymond Aron zu seinem Freund Sartre: «Siehst du, mon petit camarade, wenn du Phänomenologe bist, kannst du über diesen Cocktail sprechen, und das ist dann Philoso- phie!» Der einfache Satz war die Geburtsstunde einer neuen Bewe- gung, die sich in Jazzclubs und Cafés verbreitete. Sie inspirierte Musi- ker und Schriftsteller, erregte Abscheu im Bürgertum und befruchtete Feminismus, Antikolonialismus und 68er-Revolte. Sarah Bakewell erzählt in diesem Buch erstmals die Geschichte der Existenzialisten. Im Mittelpunkt stehen die Antipoden Heidegger und Sartre, der eine in seiner Hütte im Schwarzwald dem Sein nachsin- nend, der andere in Pariser Cafés wie besessen schreibend. Aber es geht auch um Husserl und Merleau-Ponty, Simone de Beauvoir, Albert Camus, Iris Murdoch, Colin Wilson und viele andere. Am Ende ster- ben die Protagonisten und verlassen das Café. Doch Sarah Bakewells meisterhafte Kollektivbiographie lässt sie wieder lebendig werden und uns teilhaben an ihren Gesprächen über das Sein, die Freiheit und Ap- rikosencocktails. Sarah Bakewell lebt als Schriftstellerin in London, wo sie außerdem Creative Writing an der City University lehrt und für den National Trust seltene Bücher katalogisiert. Ihre geniale Biographie «Wie soll ich leben? oder Das Leben Montaignes in einer Frage und zwanzig Antworten» (C.H.Beck Paperback, 2016) wurde zu einem internationa- len Bestseller, ausgezeichnet mit dem Duff Cooper Prize for Non-Fic- tion und dem National Books Critics Circle Award for Biography. -

In the Hot Seat the Regeneration Game RTS STUDENT TELEVISION AWARDS 2016 3 JUNE 1:00Pm BFI Southbank, London SE1 8XT

April 2016 In the hot seat The regeneration game RTS STUDENT TELEVISION AWARDS 2016 3 JUNE 1:00pm BFI Southbank, London SE1 8XT www.rts.org.uk Journal of The Royal Television Society April 2016 l Volume 53/4 From the CEO The RTS is still buzz- It was wonderful to see Lenny Henry implications of the rise of multichan- ing from this year’s being presented with the Judges’ nel networks in the early-evening Programme Awards, Award. The honour recognises event “Beyond YouTube”. Thanks to held at Mayfair’s Lenny’s huge contribution to raising Kate Bulkley for being such an erudite Grosvenor House the issue of diversity in our industry chair and to all the panellists. Hotel. Richard and keeping it high on all of our If data is your thing, don’t miss “Big Madeley was a agendas. Data: What’s the big deal?”, which will superb host, handling an occasionally Away from the glamour of Grosvenor be held at The Hospital Club in London boisterous crowd with good humour House, the RTS was treated to a very on 19 April. Tickets are selling fast so, and tact. Congratulations to all the thoughtful speech from Channel 4’s if you haven’t already booked, I’d winners and nominees. Chief Creative Officer, Jay Hunt, deliv- recommend doing so right away. Of the 200 or so jurors this year, ered in the inspirational surroundings I can reveal that 52% were female of the British Museum. and 27% were black or minority Thanks to Jay and to the evening’s ethnic.