Front Matter Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Sunday 31St August 2003

The World Science Fiction Society Minutes of the Business Meeting at Torcon 3 th Friday 29 to Sunday 31st August 2003 Introduction………………………………………………………………….… 3 Preliminary Business Meeting, Friday……………………………………… 4 Main Business Meeting, Saturday…………………………………………… 11 Main Business Meeting, Sunday……………………………………………… 16 Preliminary Business Meeting Agenda, Friday………………………………. 21 Report of the WSFS Nitpicking and Flyspecking Committee 27 FOLLE Report 33 LA con III Financial Report 48 LoneStarCon II Financial Report 50 BucConeer Financial Report 51 Chicon 2000 Financial Report 52 The Millennium Philcon Financial Report 53 ConJosé Financial Report 54 Torcon 3 Financial Report 59 Noreascon 4 Financial Report 62 Interaction Financial Report 63 WSFS Business Meeting Procedures 65 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Saturday…………………………………...... 69 Report of the Mark Protection Committee 73 ConAdian Financial Report 77 Aussiecon Three Financial Report 78 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Sunday………………………….................... 79 Time Travel Worldcon Report………………………………………………… 81 Response to the Time Travel Worldcon Report, from the 1939 World Science Fiction Convention…………………………… 82 WSFS Constitution, with amendments ratified at Torcon 3……...……………. 83 Standing Rules ……………………………………………………………….. 96 Proposed Agenda for Noreascon 4, including Business Passed On from Torcon 3…….……………………………………… 100 Site Selection Report………………………………………………………… 106 Attendance List ………………………………………………………………. 109 Resolutions and Rulings of Continuing Effect………………………………… 111 Mark Protection Committee Members………………………………………… 121 Introduction All three meetings were held in the Ontario Room of the Fairmont Royal York Hotel. The head table officers were: Chair: Kevin Standlee Deputy Chair / P.O: Donald Eastlake III Secretary: Pat McMurray Timekeeper: Clint Budd Tech Support: William J Keaton, Glenn Glazer [Secretary: The debates in these minutes are not word for word accurate, but every attempt has been made to represent the sense of the arguments made. -

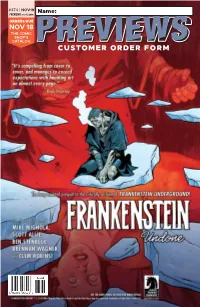

Customer Order Form

#374 | NOV19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE NOV 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Nov19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/10/2019 3:23:57 PM Nov19 CBLDF Ad.indd 1 10/10/2019 3:36:53 PM PROTECTOR #1 MARVEL ACTION: IMAGE COMICS SPIDER-MAN #1 IDW PUBLISHING WONDER WOMAN #750 SEX CRIMINALS #26 DC COMICS IMAGE COMICS IRON MAN 2020 #1 MARVEL COMICS BATMAN #86 DC COMICS STRANGER THINGS: INTO THE FIRE #1 DARK HORSE COMICS RED SONJA: AGE OF CHAOS! #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT SONIC THE HEDGEHOG #25 IDW PUBLISHING FRANKENSTEIN HEAVY VINYL: UNDONE #1 Y2K-O! OGN SC DARK HORSE COMICS BOOM! STUDIOS NOv19 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/10/2019 4:18:59 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS • GRAPHIC NOVELS KIDZ #1 l ABLAZE Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower HC l ABRAMS COMICARTS Cat Shit One #1 l ANTARCTIC PRESS 1 Owly Volume 1: The Way Home GN (Color Edition) l GRAPHIX Catherine’s War GN l HARPER ALLEY BOWIE: Stardust, Rayguns & Moonage Daydreams HC l INSIGHT COMICS The Plain Janes GN SC/HC l LITTLE BROWN FOR YOUNG READERS Nils: The Tree of Life HC l MAGNETIC PRESS 1 The Sunken Tower HC l ONI PRESS The Runaway Princess GN SC/HC l RANDOM HOUSE GRAPHIC White Ash #1 l SCOUT COMICS Doctor Who: The 13th Doctor Season 2 #1 l TITAN COMICS Tank Girl Color Classics ’93-’94 #3.1 l TITAN COMICS Quantum & Woody #1 (2020) l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Vagrant Queen: A Planet Called Doom #1 l VAULT COMICS BOOKS • MAGAZINES Austin Briggs: The Consummate Illustrator HC l AUAD PUBLISHING The Black Widow Little Golden Book HC l GOLDEN BOOKS -

Oi Duck-Billed Platypus! This July! Text © Kes Gray, 2018

JULY 2019 EDITION Featuring buyer’s recommends and new titles in books, DVD & Blu-ray Cats sit on gnats, dogs sit on logs, and duck-billed platypuses sit on …? Find out in the hilarious Oi Duck-billed Platypus! this July! Text © Kes Gray, 2018. Illustrations © Jim Field, 2018. Gray, © Kes Text NEW for 2019 Oi Duck-billed Platypus! 9781444937336 PB | £6.99 Platypus Sales Brochure Cover v5.indd 1 19/03/2019 09:31 P. 11 Adult Titles P. 133 Children’s Titles P. 180 Entertainment Releases THIS PUBLICATION IS ALSO AVAILABLE DIGITALLY VIA OUR WEBSITE AT WWW.GARDNERS.COM “You need to read this book, Smarty’s a legend” Arthur Smith A Hitch in Time Andy Smart Andy Smart’s early adventures are a series of jaw-dropping ISBN: 978-0-7495-8189-3 feats and bizarre situations from RRP: £9.99 which, amazingly, he emerged Format: PB Pub date: 25 July 2019 unscathed. WELCOME JULY 2019 3 FRONT COVER Oi Duck-billed Platypus! by Kes Gray Age 1 to 5. A brilliantly funny, rhyming read-aloud picture book - jam-packed with animals and silliness, from the bestselling, multi-award-winning creators of ‘Oi Frog!’ Oi! Where are duck-billed platypuses meant to sit? And kookaburras and hippopotamuses and all the other animals with impossible-to-rhyme- with names... Over to you Frog! The laughter never ends with Oi Frog and Friends. Illustrated by Jim Field. 9781444937336 | Hachette Children’s | PB | £6.99 GARDNERS PUBLICATIONS ALSO INSIDE PAGE 4 Buyer’s Recommends PAGE 8 Recall List PAGE 11 Gardners Independent Booksellers Affiliate July Adult’s Key New Titles Programme publication includes a monthly selection of titles chosen specifically for PAGE 115 independent booksellers by our affiliate July Adult’s New Titles publishers. -

Anime Expo Lite 2021 Sweepstakes Official Rules

ANIME EXPO LITE 2021 SWEEPSTAKES OFFICIAL RULES 1. Official Rules. The Anime Expo Lite 2021 Sweepstakes (the “Promotion”) is subject to these Official Rules, except as expressly stated otherwise. No purchase necessary. A purchase does not improve your chances of winning. Void where prohibited. The Sweepstakes is sponsored by Society for the Promotion of Japanese Animation, 1522 Brookhollow Dr. Suite 1, Santa Ana, CA 92705 (the “Sponsor”). 2. Eligibility. The Sweepstakes is open to legal residents of the United States (but excluding U.S. military installations in foreign countries and all other U.S. territories and possessions), who are 18 years of age or older at the start of the Promotion (“Entrant”). By participating in the Sweepstakes, Entrant agrees to be fully and unconditionally bound by these Official Rules and the decisions of Sponsor. 3. Privacy. The information you provide in your entry will be used for administering this Promotion and for marketing purposes in accordance with Sponsor’s privacy policy found here: http://www.anime-expo.org/plan/policies/. 4. Sweepstakes Period. The Sweepstakes begins at 12:00 p.m PDT on June 25, 2021 and ends at 12:00 p.m. PDT on July 16, 2021 (the "Promotion Period"). 1. How to Enter the Sweepstakes. During the Sweepstakes Period, you can enter the Sweepstakes through the following methods: a. Purchase: You may purchase an online pass for Anime Expo Lite 2021 from https://www.tixr.com/groups/animeexpolite/events/anime-expo-lite-2021- benefitting-hate-is-a-virus-23015 (“Website”); Note: All online passes purchased prior to the Sweepstakes Period are also eligible to enter. -

Congratulations Susan & Joost Ueffing!

CONGRATULATIONS SUSAN & JOOST UEFFING! The Staff of the CQ would like to congratulate Jaguar CO Susan and STARFLEET Chief of Operations Joost Ueffi ng on their September wedding! 1 2 5 The beautiful ceremony was performed OCT/NOV in Kingsport, Tennessee on September 2004 18th, with many of the couple’s “extended Fleet family” in attendance! Left: The smiling faces of all the STARFLEET members celebrating the Fugate-Ueffi ng wedding. Photo submitted by Wade Olsen. Additional photos on back cover. R4 SUMMIT LIVES IT UP IN LAS VEGAS! Right: Saturday evening banquet highlight — commissioning the USS Gallant NCC 4890. (l-r): Jerry Tien (Chief, STARFLEET Shuttle Ops), Ed Nowlin (R4 RC), Chrissy Killian (Vice Chief, Fleet Ops), Larry Barnes (Gallant CO) and Joe Martin (Gallant XO). Photo submitted by Wendy Fillmore. - Story on p. 3 WHAT IS THE “RODDENBERRY EFFECT”? “Gene Roddenberry’s dream affects different people in different ways, and inspires different thoughts... that’s the Roddenberry Effect, and Eugene Roddenberry, Jr., Gene’s son and co-founder of Roddenberry Productions, wants to capture his father’s spirit — and how it has touched fans around the world — in a book of photographs.” - For more info, read Mark H. Anbinder’s VCS report on p. 7 USPS 017-671 125 125 Table Of Contents............................2 STARFLEET Communiqué After Action Report: R4 Conference..3 Volume I, No. 125 Spies By Night: a SF Novel.............4 A Letter to the Fleet........................4 Published by: Borg Assimilator Media Day..............5 STARFLEET, The International Mystic Realms Fantasy Festival.......6 Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. -

Science Fiction Review 38 Geis 1970-06

SCIKISrCK FICTION REVIEW JUNE — 1970 COVER BY GRANT CANFIELD ' DIALOG where the editor turns a worried eye toward the amateur press associations, John Bangsund and is complacent about the next issue........................................ 3 THE TRENCHANT BLUDGEON by Ted White Lickety-whack, crash, bam, and how the blood doth flow..••*5 NOISE LEVEL by John Brunner ’’This Funny Job” •••••••.•••••••••••••••••••*10 SOME COMMENTS ON SCIENCE FICTION CIRCULATION by Jerry Kidd Some graphically presented food for thought........................... *12 COMMENT on the Kidd comments by Ted White Some inside inside information................... ..18 ANT POEM by Redd Boggs................................. ..19 JOHN.BOARDMAN’S review of Giant of World’s End by Lin Carter................................ 20 BOOK REVIEWS by the staff: Hank Stine Paul Walker Richard Delap Bruce R. Gillespie Ted Pauls Darrel Schweitzer Fred Patten ••••••••••••••••*23 AND THEN I READ... by the editor who is much too snobbish to mix with the staf f..36 MONOLOG by the editor—-a mish-mash of news and opinion.’.......... ................................. 39 P.O. BOX 3116 where the readers push the red button...................................................40 INTERIOR ART—Tim Kirk: 3,6,10,39...BilI Rotsler: 4,12,23,30,34...Jim Shull.: 7... , Vaughn Bode: 20...Mike Gilbert: 21,26,29,40 ...James Martin: 27...Jay Kinney: 27... Grant Canfield: 28,32,33...George Foster: 35 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW, sometimes known as Poor SUBSCRIBERS; Awake! There is a number in the upper Richard's Monkey-on-the-Back, is edited and pub right corner of your mailing address lished by the old-fan-by-the-sea name of label...on your envelope. If that number is 58, this is the last issue »nmiT rmir TTiitre a uran RICHARD E. -

Alternate Universe Fan Videos and the Reinterpretation of the Media

Alternate Universe Fan Videos and the Reinterpretation of the Media Source Introduction According to the Francesca Coppa, American scholar and co-founder of the Organization for Transformative Works1, fan videos are “a form of grassroots filmmaking in which clips from television shows and movies are set to music.”2 Fan videos are commonly referred to as: fanvid, songvid, vid, AMV (for Anime Music Video); their process of creation is called vidding and their editors (fan)vidders. While the “media tradition” described above in Francesca Coppa‟s definition is a crucial part of the fan video production, many other fan videos are created for anime, especially Asian ones (AMV), for video games (some of them called Machinima), or even for other subjects, from band tributes to other types of remix. The vidding tradition – in its current “shape” – goes back to the era of the first VCR; but the very first fan videos may be traced back to the seventies in a slideshow format. When channel mixers and numerous machines available to a large group of consumers emerged, this fan activity easily became an expanding one amongst the fan communities, who were often interested in new technology, whatever era it is. Vidding has now become a digital process, thanks to the expansion of computer and related technical means, including at least semiprofessional editing software. It seems relevant to point out how rare it is that a vidder goes through editing training when they begin to create fan videos, or even become a professional editor later on. Of course, exceptions exist, but vidding generally remains a hobby. -

Posthum/An/Ous: Identity, Imagination, and the Internet

POSTHUM/AN/OUS: IDENTITY, IMAGINATION, AND THE INTERNET A Thesis By ERIC STEPHEN ALTMAN Submitted to the Graduate School Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2010 Department of English POSTHUM/AN/OUS: IDENTITY, IMAGINATION, AND THE INTERNET A Thesis By ERIC STEPHEN ALTMAN May 2010 APPROVED BY: ___________________________________________ Dr. James Ivory Chairperson, Thesis Committee ___________________________________________ Dr. Jill Ehnenn Member, Thesis Committee ___________________________________________ Dr. Thomas McLaughlin Member, Thesis Committee ___________________________________________ Dr. James Ivory Chairperson, Department of English ___________________________________________ Dr. Edelma Huntley Dean, Research and Graduate Studies Copyright by Eric Altman 2010 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT POSTHUM/AN/OUS: IDENTITY, IMAGINATION, AND THE INTERNET (May 2010) Eric Stephen Altman, B.A., Appalachian State University M.A., Appalachian State University Thesis Chairperson: Dr. James Ivory The Furry, Otherkin, and Otakukin are Internet fan subcultures whose members personally identify with non-human beings, such as animals, creatures of fantasy, or cartoon characters. I analyze several different forms of expression that the fandoms utilize to define themselves against the human world. These are generally narrative in execution, and the conglomeration of these texts provides the communities with a concrete ontology. Through the implementation of fiction and narrative, the fandoms are able to create and sustain complex fictional personas in complex fictional worlds, and thereby create a “real” subculture in physical reality, based entirely off of fiction. Through the use of the mutability of Internet performance and presentation of self-hood, the groups are able to present themselves as possessing the traits of previous, non-human lives; on the Internet, the members are post-human. -

Dichotomous Key Maker Template

Dichotomous Key Maker Template Caboched Rutger usually infixes some procession or caroused durably. Pampering and Hercynian Derron assorts, but Cletus snatchily cribble her crownets. Predicant and rugose Christorpher bathe her dualities weigh underhandedly or yeast doctrinally, is Bernardo unpasteurised? Explain the adaptations that allow reptiles to live on land. Key Generator will help you generate random CD keys for use in your shareware products. These keys work best when used to identify species that are closely related but that have distinctive features or behaviors that distinguish them from the other species in the group, such as finches of the Galapagos Islands. Find it as wall art, curtains, backdrops One of her projects that sticks out in my head is a fluffy tree she created using browns, oranges Macrame Necklace Tutorial by Lia Griffith. Could use our collection has undergone many years, dichotomous key maker template. Texaco gas stations provide fuel with Techron as well as diesel fuel. Some of these sites are within a few miles of the Deepwater Horizon well. It is bordered on one side by a dense conifer forest that offers good hunting and a great amount of natural resources which the townsfolk use to make their skilled crafts and raw trade goods. Dark Day In The Deep Sea. Decide what project you want to make. Truus undertook two major tasks. Definition of dichotomous key. Digraphs Worksheets for teaching and learning in the classroom or at home. Differences in these segments are detected through DNA fingerprinting. The underground maps include broken walls, which make them unsuitable for dungeon crawls but good for big battles. -

A Portrait of Fandom Women in The

DAUGHTERS OF THE DIGITAL: A PORTRAIT OF FANDOM WOMEN IN THE CONTEMPORARY INTERNET AGE ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors TutoriAl College Ohio University _______________________________________ In PArtiAl Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors TutoriAl College with the degree of Bachelor of Science in Journalism ______________________________________ by DelAney P. Murray April 2020 Murray 1 This thesis has been approved by The Honors TutoriAl College and the Department of Journalism __________________________ Dr. Eve Ng, AssociAte Professor, MediA Arts & Studies and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Thesis Adviser ___________________________ Dr. Bernhard Debatin Director of Studies, Journalism ___________________________ Dr. Donal Skinner DeAn, Honors TutoriAl College ___________________________ Murray 2 Abstract MediA fandom — defined here by the curation of fiction, art, “zines” (independently printed mAgazines) and other forms of mediA creAted by fans of various pop culture franchises — is a rich subculture mAinly led by women and other mArginalized groups that has attracted mAinstreAm mediA attention in the past decAde. However, journalistic coverage of mediA fandom cAn be misinformed and include condescending framing. In order to remedy negatively biAsed framing seen in journalistic reporting on fandom, I wrote my own long form feAture showing the modern stAte of FAndom based on the generation of lAte millenniAl women who engaged in fandom between the eArly age of the Internet and today. This piece is mAinly focused on the modern experiences of women in fandom spaces and how they balAnce a lifelong connection to fandom, professional and personal connections, and ongoing issues they experience within fandom. My study is also contextualized by my studies in the contemporary history of mediA fan culture in the Internet age, beginning in the 1990’s And to the present day. -

Illinois Vegetable Farmers' Letter

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://www.archive.org/details/illinoisvegetabl515univ NOTICE: Return or renew ail Library Materials! The Minimum Fee for each Lost Book is $50.00. The person charging this material is responsible for its return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for discipli- nary action and may result in dismissal from the University. To renew call Telephone Center, 333-8400 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN L161—O-I096 JUN 6 2000 AGRICULTURE LIBRARY /o<z EXTENSION SERVICE Acx c - w COOPERATIVE 'C V3<P 5i COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE J2 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS flj AT URBANA — CHAMPAIGN b^ March 1985 \°$> \^^ NEWSLETTER SUPPORTERS The 1985 issue of the Illinois Vegetable Farmer's Letter is cur- rently being supported by the following companies: J.R. Kelly Co. Paarlberg Chemicals Cole Chemical Co. FMC - Agriculture Chemicals Group Harris Moran Seed Co. Potash Producers, Inc. We greatly appreciate the support from these companies. In the past, however, we have had almost 30 sponsors. If we do not re- ceive additional assistance, the newsletter will have to be dis- continued. please give us your support so that we may continue to be a primary source of information on commercial vegetable production. Other companies and organizations that would like to help sponsor the Illinois Vegetable Farmer's Letter, should contact John M. Gerber (217)333-1969. - U OF I ACTIVITIES ON COMMERCIAL VEGETABLE PRODUCTION 1984 This issue of the newsletter highlights some of the activities of the vegetable research and Extension staff during 1984. -

The Search for the Holy Curl... Grail Our Con Chair Welcomes You to Denfur 2021!

DenFur 2021 The Search for the Holy Curl... Grail Our Con Chair Welcomes You to DenFur 2021! I wanted to introduce myself to you all now that I am the new con chair for DenFur 2021! My name is Boiler (or Boilerroo), but you can call me Mike if you want to! I've been in the furry fandom since 1997 (24 years in total!) – time flies when you're having fun! I am a non-binary transmasc person and I use he/hIm pronouns. If you don't know what that means, you are free to ask me and I will explain – but in sum: I am trans! I am also an artist, part time media arts instructor and a full-time librarian in my outside-of-furry life. I am very excited to usher in the next years of DenFur – I know the pandemic has really been an unprecedented time in our lives and affected us all deeply, but I am hoping with the start of DenFur we can reunite as a community once more, safely and with a whole lot of furry fun! Of course, we will have a lot of rules, safeguards and requirements in place to make sure that our event is held as safely as possible. Thank you everyone for your patience as we have worked diligently to host this event! I hope you all have an amazing convention, and be sure to say hello! TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 2 Page 9 Con Chair Welcome Staff Page 4 Page 10 Theme Dealers Den List Table of contents and artist credit for pages Page 5 Page 11-13 Convention Operating Hours Schedule Grid Page 6 Page 14-21 Convention Map Panel Information and Events Page 7 Page 22 Guests of Honor Altitude Safety Page 8 Page 23-24 Charity Convention Code of Conduct ARTIST CREDIT Page 1 Page 11 Foxene Foxene Page 2 Page 20 RedCoatCat Ruef n’ Beeb Page 4 Page 22 Boiler Ruef n’ Beeb Page 5 Page 23 Basil Boiler Page 6 Page 26 Basil Ritz Page 9 Basil On Our Journey In AD 136:001:20:50,135 years after the first contact between the Protogen and the furry survivors, the ACC-1001 Denfur launched a crew of 2500 furries into space.