Fragmentation of the Syrian State Since 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

Annex Ii: List of Natural and Legal Persons, Entities Or Bodies Referred to in Article 14 and 15 (1)(A)

VEDLEGG II ANNEX II: LIST OF NATURAL AND LEGAL PERSONS, ENTITIES OR BODIES REFERRED TO IN ARTICLE 14 AND 15 (1)(A) A. Persons Name Identifying Reasons Date of listing information Date of birth: President of the 23.05.2011 (ب شار) Bashar .1 September Republic; person 11 (اﻷ سد) Al-Assad 1965; authorising and Place of birth: supervising the Damascus; crackdown on diplomatic demonstrators. passport No D1903 Date of birth: Commander of the 09.05.2011 (ماهر) Maher .2 (a.k.a. Mahir) 8 December 1967; Army's 4th ,diplomatic Armoured Division (اﻷ سد) Al-Assad passport No 4138 member of Ba'ath Party Central Command, strongman of the Republican Guard; brother of President Bashar Al-Assad; principal overseer of violence against demonstrators. 3. Ali ( ) Date of birth: Director of the 09.05.2011 Mamluk ( ) 19 February 1946; National Security (a.k.a. Mamlouk) Place of birth: Bureau. Former Head Damascus; of Syrian Diplomatic passport Intelligence Directorate No 983 (GID) involved in violence against demonstrators Former Head of the 09.05.2011 (عاطف) Atej .4 (a.k.a. Atef, Atif) Political Security ;Directorate in Dara'a (ن ج يب) Najib (a.k.a. Najeeb) cousin of President Bashar Al-Assad; involved in violence against demonstrators. Name Identifying Reasons Date of listing information Date of birth: Colonel and Head of 09.05.2011 (حاف ظ) Hafiz .5 April 1971; Unit in General 2 مخ لوف ) Makhluf )(a.k.a. Hafez Place of birth: Intelligence Makhlouf) Damascus; Directorate, diplomatic Damascus Branch; passport No 2246 cousin of President Bashar Al-Assad; close to Maher Al- Assad; involved in violence against demonstrators. -

The Syrian Crisis: an Analysis of Neighboring Countries' Stances

POLICY ANALYSIS The Syrian Crisis: An Analysis of Neighboring Countries’ Stances Nerouz Satik and Khalid Walid Mahmoud | October 2013 The Syrian Crisis: An Analysis of Neighboring Countries’ Stances Series: Policy Analysis Nerouz Satik and Khalid Walid Mahmoud | October 2013 Copyright © 2013 Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies. All Rights Reserved. ____________________________ The Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies is an independent research institute and think tank for the study of history and social sciences, with particular emphasis on the applied social sciences. The Center’s paramount concern is the advancement of Arab societies and states, their cooperation with one another and issues concerning the Arab nation in general. To that end, it seeks to examine and diagnose the situation in the Arab world - states and communities- to analyze social, economic and cultural policies and to provide political analysis, from an Arab perspective. The Center publishes in both Arabic and English in order to make its work accessible to both Arab and non-Arab researchers. Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies PO Box 10277 Street No. 826, Zone 66 Doha, Qatar Tel.: +974 44199777 | Fax: +974 44831651 www.dohainstitute.org Table of Contents Introduction 1 The Lebanese Position toward the Syrian Revolution 1 Factors behind the Lebanese stances 8 Internationally 14 Domestically 14 The Jordanian Stance 15 Regional and International Influences 18 The Syrian Revolution and the Arab Levant 22 NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES’ STANCES ON SYRIA Introduction The Arab Levant region has significant geopolitical importance in the global political map, particularly because of its diverse ethnic and religious identities and the complexity of its social and political structures. -

Rojavadevrimi+Full+75Dpi.Pdf

Kitaba ilişkin bilinmesi gerekenler Elinizdeki kitabın orijinali 2014 ve 2015 yıllarında Almanca dilinde üç yazar tarafından yazıldı ve Rosa Lüksemburg Vakfı’nın desteğiyle “VSA Verlag” adlı yayınevi tarafından Almanya’da yayınlandı. 2018 yılında Almanca dilinde 4. baskısı güncellenip basılarak önemli ilgi gören bu kitap, 2016 Ekim ayında “Pluto Press” adlı yayınevi tarafından İngilizce dilinde Birleşik Krallık ‘ta yayınlandı. Bu kitabın İngilizce çevirisi ABD’de yaşayan yazar ve aktivist Janet Biehl tarafından yapıldı ve sonrasında üç yazar tarafından 2016 ilkbaharında güncellendi. En başından beri kitabın Türkçe dilinde de basılıp yayınlanası için bir planlama yapıldı. Bu amaçla bir grup gönüllü İngilizce versiyonu temel alarak Türkçe çevirisini yaptı. Türkiye’deki siyasal gelişme ve zorluklardan dolayı gecikmeler ortaya çıkınca yazarlar kitabın basılmasını 2016 yılından daha ileri bir tarihe alma kararını aldı. Bu sırada tekrar Rojava’ya giden yazarlar, elde ettikleri bilgilerle Türkçe çeviriyi doğrudan Türkçe dilinde 2017 ve 2018 yıllarında güncelleyip genişletti. Bu gelişmelere redaksiyon çalışmaları da eklenince kitabın Türkçe dilinde yayınlanması 2018 yılında olması gerekirken 2019 yılına sarktı. 2016 yılından beri kitap ayrıca Farsça, Rusça, Yunanca, İtalyanca, İsveççe, Polonca, Slovence, İspanyolca dillerine çevrilip yayınlandı. Arapça ve Kürtçe çeviriler devam etmektedir. Kitap Ağustos 2019’da yayınlandı. Ancak kitapta en son Eylül 2018’de içeriksel güncellenmeler yapıldı. 2018 yazın durum ve atmosferine göre yazıldı. Kitapta kullanılan resimlerde eğer kaynak belirtilmemişse, resimler yazarlara aittir. Aksi durumda her resmin altında resimlerin sahibi belirtilmektedir. Kapaktaki resim Rojava’da kurulmuş kadın köyü Jinwar’ı göstermekte ve Özgür Rojava Kadın Vakfı’na (WJAR) aittir. Bu kitap herhangi bir yayınevi tarafından yayınlanmamaktadır. Herkes bu kitaba erişimde serbesttir. Kitabı elektronik ve basılı olarak istediğiniz gibi yayabilirsiniz, ancak bu kitaptan gelir ve para elde etmek yazarlar tarafından izin verilmemektedir. -

S/2012/503 Consejo De Seguridad

Naciones Unidas S/2012/503 Consejo de Seguridad Distr. general 16 de octubre de 2012 Español Original: inglés Cartas idénticas de fecha 28 de junio de 2012 dirigidas al Secretario General y al Presidente del Consejo de Seguridad por el Representante Permanente de la República Árabe Siria ante las Naciones Unidas Siguiendo instrucciones de mi Gobierno y en relación con mis cartas de fechas 16 a 20 y 23 a 25 de abril, 7, 11, 14 a 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 y 31 de mayo y 1, 4, 6, 7, 11, 19, 20, 25 y 27 de junio de 2012, tengo el honor de trasmitir adjunta una lista pormenorizada de las violaciones del cese de la violencia cometidas por grupos armados en Siria el 24 de junio de 2012 (véase el anexo). Agradecería que la presente carta y su anexo se distribuyeran como documento del Consejo de Seguridad. (Firmado) Bashar Ja’afari Embajador Representante Permanente 12-55140 (S) 241012 241012 *1255140* S/2012/503 Anexo de las cartas idénticas de fecha 28 de junio de 2012 dirigidas al Secretario General y al Presidente del Consejo de Seguridad por el Representante Permanente de la República Árabe Siria ante las Naciones Unidas [Original: árabe] Sunday, 24 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. On 23 June 2012 at 2020 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on a military barracks headquarters in Rif Dimashq. 2. On 23 June 2012 at 2100 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on law enforcement checkpoints in Shaffuniyah, Shumu' and Umara' in Duma, killing Private Muhammad al-Sa'dah and wounding three soldiers, including a first lieutenant. -

Security Council Distr.: General 8 January 2013

United Nations S/2012/401 Security Council Distr.: General 8 January 2013 Original: English Identical letters dated 4 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, and following my letters dated 16 to 20 and 23 to 25 April, 7, 11, 14 to 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 and 31 May, and 1 and 4 June 2012, I have the honour to attach herewith a detailed list of violations of cessation of violence that were committed by armed groups in Syria on 3 June 2012 (see annex). It would be highly appreciated if the present letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Bashar Ja’afari Ambassador Permanent Representative 13-20354 (E) 170113 210113 *1320354* S/2012/401 Annex to the identical letters dated 4 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council [Original: Arabic] Sunday, 3 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. On 2/6/2012, from 1600 hours until 2000 hours, an armed terrorist group exchanged fire with law enforcement forces after the group attacked the forces between the orchards of Duma and Hirista. 2. On 2/6/2012 at 2315 hours, an armed terrorist group detonated an explosive device in a civilian vehicle near the primary school on Jawlan Street, Fadl quarter, Judaydat Artuz, wounding the car’s driver and damaging the car. -

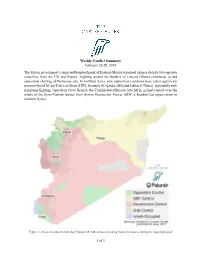

Weekly Conflict Summary

Weekly Conflict Summary February 22-28, 2018 The Syrian government’s siege and bombardment of Eastern Ghouta remained intense despite two separate ceasefires from the UN and Russia. Fighting around the borders of Eastern Ghouta continued, as did opposition shelling of Damascus city. In northern Syria, new opposition coalitions have taken significant territory from Hai’yat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS, formerly Al-Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra), apparently with minimum fighting. Operation Olive Branch, the Turkish-led offensive into Afrin, gained control over the whole of the Syria-Turkish border from Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF, a Kurdish-led organization in northern Syria). Figure 1 - Areas of control in Syria by February 28, with arrows indicating fronts of advances during the reporting period 1 of 3 Weekly Conflict Summary – February 22-28, 2018 Eastern Ghouta Figure 2 - Situation in Eastern Ghouta by February 28 Strikes on opposition-held Eastern Ghouta continued throughout this reporting period. The situation in the besieged area is increasingly dire, with reports of a lack of access to basic nutrition, repeated attacks on hospitals, and mounting civilian casualties. On February 24, the UN Security Council adopted a resolution calling for a 30-day nation-wide ceasefire “without delay”. The resolution was adopted after repeated delays due to disagreements between the US and Russians on the text before the vote. The UN vote was intended to allow emergency aid deliveries to the region’s hardest-hit areas. Despite the resolution, fighting has continued throughout most of Syria, and has been particularly intense in Eastern Ghouta and in the northwestern Afrin region. -

Into the Tunnels

REPORT ARAB POLITICS BEYOND THE UPRISINGS Into the Tunnels The Rise and Fall of Syria’s Rebel Enclave in the Eastern Ghouta DECEMBER 21, 2016 — ARON LUND PAGE 1 In the sixth year of its civil war, Syria is a shattered nation, broken into political, religious, and ethnic fragments. Most of the population remains under the control of President Bashar al-Assad, whose Russian- and Iranian-backed Baʻath Party government controls the major cities and the lion’s share of the country’s densely populated coastal and central-western areas. Since the Russian military intervention that began in September 2015, Assad’s Syrian Arab Army and its Shia Islamist allies have seized ground from Sunni Arab rebel factions, many of which receive support from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, or the United States. The government now appears to be consolidating its hold on key areas. Media attention has focused on the siege of rebel-held Eastern Aleppo, which began in summer 2016, and its reconquest by government forces in December 2016.1 The rebel enclave began to crumble in November 2016. Losing its stronghold in Aleppo would be a major strategic and symbolic defeat for the insurgency, and some supporters of the uprising may conclude that they have been defeated, though violence is unlikely to subside. However, the Syrian government has also made major strides in another besieged enclave, closer to the capital. This area, known as the Eastern Ghouta, is larger than Eastern Aleppo both in terms of area and population—it may have around 450,000 inhabitants2—but it has gained very little media interest. -

Assessing the Role of Agriculture in Syrian Territories

ASSESSING THE ROLE OF AGRICULTURE IN SYRIAN TERRITORIES a context analysis in the Districts of Afrin, Atarib and Idleb Authors Lamberto Lamberti is CIHEAM Bari officer in the field of Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development. His expertise includes livelihood analysis and strengthening, with experience on communities suffering of conflict and post conflict situations. He coordinated the survey team. Patrizia Pugliese is international officer and senior researcher at CIHEAM Bari, agro-economist, with research and cooperation experience in the fields of territorial integrated development, value chain collaboration, sustainable agriculture and women’s economic empowerment with specific reference to Mediterranean contexts. Marie Reine Bteich is a senior researcher at CIHEAM Bari, agro-economist with research and cooperation experience in socio-economic data management, agro-food value chain analysis and women’s empowerment. She has mostly worked in Mediterranean countries. Cesare Zanasi is Associate Professor at Bologna University on Agriculture and Food Economics, with experience in international cooperation for development studies applied to the agro-food chains and sustainable rural development. Cosimo Rota, Research Fellow at Bologna University, with expertise in international research projects and business advising, in particular in the field of agri-food economics. His main topics are market research, data insight and analytics, rural development and sustainability. Acknowledgements The survey team wants to express its gratitude -

'Till Martyrdom Do Us Part': Gender and the ISIS Phenomenon

‘Till Martyrdom Do Us Part’ Gender and the ISIS Phenomenon erin marie saltman melanie smith About this paper This report represents the second publication in ISD’s Women and Extremism (WaE) programme, launched in January 2015 to fill a large blind spot in the evolution of the global extremist threat. This report also builds upon ICSR’s research into the foreign fighter phenomenonlxviii. Questions are now being posed as to how and why females are being recruited, what role they play within violent extremist organizations, and what tools will best work to counter this new threat. Yet very little work has been done to not only answer these questions but to build sustainable preventative measures. WaE serves to pioneer new research, develop global networks, seed local initiatives, and influence social media, in-line with work already being piloted by the ISD. About the authors Dr. Erin Marie Saltman is a Senior Researcher at ISD overseeing research and project development on Women and Extremism (WaE). WaE aims to fully analyse the radicalisation processes of women into violent extremist networks as well as increase the role women play in countering extremism. Erin’s background includes research and analysis work on both far-right and Islamist processes of radicalisation, political socialization and counter-extremism programmes. She regularly advises governments and security sectors across Europe and North America on issues related to online extremism and the role of the internet in radicalisation. Erin holds a PhD in political science from University College London. Melanie Smith is a Research Associate working on ISD’s WaE programme. -

The Factory: a Glimpse Into Syria's War Economy

REPORT SYRIA The Factory: A Glimpse into Syria’s War Economy FEBRUARY 21, 2018 — ARON LUND PAGE 1 After the October 2017 fall of Raqqa to U.S.-backed Kurdish and Arab guerrillas, the extremist group known as the Islamic State is finally crumbling. But victory came a cost: Raqqa lies in ruins, and so does much of northern Syria.1 At least one of the tools for reconstruction is within reach. An hour and a half ’s drive from Raqqa lies one of the largest and most modern cement plants in the entire Middle East, opened less than a year before the war by the multinational construction giant LafargeHolcim. If production were to be resumed, the factory would be perfectly positioned to help rebuild bombed-out cities like Raqqa and Aleppo. However, although the factory may well hold one of the keys to Syria’s future, it also has an unseemly past. In December 2017, French prosecutors charged LafargeHolcim’s former CEO with terrorism financing, having learned that its forerunner Lafarge2 was reported to have paid millions of dollars to Syrian armed groups, including the terrorist- designated Islamic State.3 The strange story of how the world’s most hated extremist group allegedly ended up receiving payments from the world’s largest cement company is worth a closer look, not just for what it tells us about the way money fuels conflict, but also for what it can teach us about Syria’s war economy—a vast ecosystem of illicit profiteering, where the worst of enemies are also partners in business. -

From the Heart of the Syrian Crisis

From the Heart of the Syrian Crisis A Report on Islamic Discourse Between a Culture of War and the Establishment of a Culture of Peace Research Coordinator Sheikh Muhammad Abu Zeid From the Heart of the Syrian Crisis A Report on Islamic Discourse Between a Culture of War and the Establishment of a Culture of Peace Research Coordinator Sheikh Muhammad Abu Zeid Adyan Foundation March 2015 Note: This report presents the conclusion of a preliminary study aimed at shedding light on the role of Sunni Muslim religious discourse in the Syrian crisis and understanding how to assess this discourse and turn it into a tool to end violence and build peace. As such, the ideas in the report are presented as they were expressed by their holders without modification. The report, therefore, does not represent any official intellectual, religious or political position, nor does it represent the position of the Adyan foundation or its partners towards the subject or the Syrian crisis. The following report is simply designed to be a tool for those seeking to understand the relationship between Islamic religious discourse and violence and is meant to contribute to the building of peace and stability in Syria. It is, therefore, a cognitive resource aimed at promoting the possibilities of peace within the framework of Adyan Foundation’s “Syria Solidarity Project” created to “Build Resilience and Reconciliation through Peace Education”. The original text of the report is in Arabic. © All rights reserved for Adyan Foundation - 2015 Beirut, Lebanon Tel: 961 1 393211