'A Thread Ofblue': Rabbi Gershon Henoch Leiner of Radzyn and His Search for Continuity in Response to Modernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 'Like Iron to a Magnet': Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence David Sclar Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/380 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence By David Sclar A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 David Sclar All Rights Reserved This Manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Prof. Jane S. Gerber _______________ ____________________________________ Date Chair of the Examining Committee Prof. Helena Rosenblatt _______________ ____________________________________ Date Executive Officer Prof. Francesca Bregoli _______________________________________ Prof. Elisheva Carlebach ________________________________________ Prof. Robert Seltzer ________________________________________ Prof. David Sorkin ________________________________________ Supervisory Committee iii Abstract “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence by David Sclar Advisor: Prof. Jane S. Gerber This dissertation is a biographical study of Moses Hayim Luzzatto (1707–1746 or 1747). It presents the social and religious context in which Luzzatto was variously celebrated as the leader of a kabbalistic-messianic confraternity in Padua, condemned as a deviant threat by rabbis in Venice and central and eastern Europe, and accepted by the Portuguese Jewish community after relocating to Amsterdam. -

A Fresh Perspective on the History of Hasidic Judaism

eSharp Issue 20: New Horizons A Fresh Perspective on the History of Hasidic Judaism Eva van Loenen (University of Southampton) Introduction In this article, I shall examine the history of Hasidic Judaism, a mystical,1 ultra-orthodox2 branch of Judaism, which values joyfully worshipping God’s presence in nature as highly as the strict observance of the laws of Torah3 and Talmud.4 In spite of being understudied, the history of Hasidic Judaism has divided historians until today. Indeed, Hasidic Jewish history is not one monolithic, clear-cut, straightforward chronicle. Rather, each scholar has created his own narrative and each one is as different as its author. While a brief introduction such as this cannot enter into all the myriad divergences and similarities between these stories, what I will attempt to do here is to incorporate and compare an array of different views in order to summarise the history of Hasidism and provide a more objective analysis, which has not yet been undertaken. Furthermore, my historical introduction in Hasidic Judaism will exemplify how mystical branches of mainstream religions might develop and shed light on an under-researched division of Judaism. The main focus of 1 Mystical movements strive for a personal experience of God or of his presence and values intuitive, spiritual insight or revelationary knowledge. The knowledge gained is generally ‘esoteric’ (‘within’ or hidden), leading to the term ‘esotericism’ as opposed to exoteric, based on the external reality which can be attested by anyone. 2 Ultra-orthodox Jews adhere most strictly to Jewish law as the holy word of God, delivered perfectly and completely to Moses on Mount Sinai. -

The Great Tekhelet Debate—Blue Or Purple? Baruch and Judy Taubes Sterman

archaeological VIEWS The Great Tekhelet Debate—Blue or Purple? Baruch and Judy Taubes Sterman FOR ANCIENT ISRAELITES, TEKHELET WAS writings of rabbinic scholars and Greek and Roman God’s chosen color. It was the color of the sumptu- naturalists had convinced Herzog that tekhelet was a ous drapes adorning Solomon’s Temple (2 Chroni- bright sky-blue obtained from the natural secretions cles 3:14) as well as the robes worn by Israel’s high of a certain sea snail, the Murex trunculus, known to priests (Exodus 28:31). Even ordinary Israelites produce a dark purple dye.* were commanded to tie one string of tekhelet to But the esteemed chemist challenged Herzog’s the corner fringes (Hebrew, tzitzit) of their gar- contention: “I consider it impossible to produce a ments as a constant reminder of their special rela- pure blue from the purple snails that are known to Tekhelet was tionship with God (Numbers 15:38–39). me,” Friedländer said emphatically.1 But how do we know what color the Biblical writ- Unfortunately, neither Herzog nor Friedländer God’s chosen ers had in mind? While tekhelet-colored fabrics and lived to see a 1985 experiment by Otto Elsner, a color. It colored clothes were widely worn and traded throughout the chemist with the Shenkar College of Fibers in Israel, ancient Mediterranean world, by the Roman period, proving that sky-blue could, in fact, be produced the drapes donning tekhelet and similar colors was the exclusive from murex dye. During a specific stage in the dyeing of Solomon’s privilege of the emperor. -

Megillat Esther

The Steinsaltz Megillot Megillot Translation and Commentary Megillat Esther Commentary by Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz Koren Publishers Jerusalem Editor in Chief Rabbi Jason Rappoport Copy Editors Caryn Meltz, Manager The Steinsaltz Megillot Aliza Israel, Consultant Esther Debbie Ismailoff, Senior Copy Editor Ita Olesker, Senior Copy Editor Commentary by Chava Boylan Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz Suri Brand Ilana Brown Koren Publishers Jerusalem Ltd. Carolyn Budow Ben-David POB 4044, Jerusalem 91040, ISRAEL Rachelle Emanuel POB 8531, New Milford, CT 06776, USA Charmaine Gruber Deborah Meghnagi Bailey www.korenpub.com Deena Nataf Dvora Rhein All rights reserved to Adin Steinsaltz © 2015, 2019 Elisheva Ruffer First edition 2019 Ilana Sobel Koren Tanakh Font © 1962, 2019 Koren Publishers Jerusalem Ltd. Maps Editors Koren Siddur Font and text design © 1981, 2019 Koren Publishers Jerusalem Ltd. Ilana Sobel, Map Curator Steinsaltz Center is the parent organization Rabbi Dr. Joshua Amaru, Senior Map Editor of institutions established by Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz Rabbi Alan Haber POB 45187, Jerusalem 91450 ISRAEL Rabbi Aryeh Sklar Telephone: +972 2 646 0900, Fax +972 2 624 9454 www.steinsaltz-center.org Language Experts Dr. Stéphanie E. Binder, Greek & Latin Considerable research and expense have gone into the creation of this publication. Rabbi Yaakov Hoffman, Arabic Unauthorized copying may be considered geneivat da’at and breach of copyright law. Dr. Shai Secunda, Persian No part of this publication (content or design, including use of the Koren fonts) may Shira Shmidman, Aramaic be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews. -

Chassidus on the Eh're Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) RE ’EH _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah The Merit of Charity Compound forms of verbs usually indicate thoroughness. Yet when the Torah tells us (14:22), “You shall fully tithe ( aser te’aser ) all the produce of your field,” our Sages derive another concept. “ Aser bishvil shetis’asher ,” they say. “Tithe in order that you shall become wealthy.” Why is this so? When the charity a person gives, explains Rav Levi Yitzchak, comes up to Heaven, its provenance is scrutinized. Why was this particular amount giv en to charity? Then the relationship to the full amount of the harvest is discovered. There is a ration of ten to one, and the amount given is one tenth of the total. In this way the entire harvest participates in the mitzvah but only in a secondary role. Therefore, if the charity was given with a full heart, the person giving the charity merits that the quality of his donation is elevated. The following year, the entire harvest is elevated from a secondary role to a primary role in the giving of the charit y. The amount of the previous year’s harvest then becomes only one tenth of the new harvest, and the giver becomes wealthy. n Story Unfortunately, there were all too many poor people who circulated among the towns and 1 Re ’eh / [email protected] villages begging for assistance in staving off starvation. -

The Mystery, Meaning and Disappearance of the Tekhelet

THE MYSTERY, MEANING AND DISAPPEARANCE OF THE TEKHELET YOSEF GREEN AND PINCHAS KAHN And the Lord spoke to Moses, saying , "Speak to the people of Israel, and bid them that they make them fringes [tzitzit ] on the borders of their garments throughout their generations, and that they put upon the fringe of the borders a thread of blue [Petil Tekhelet]. And it shall be to you for a fringe, that you may look upon it, and remem- ber all the commandments of the Lord, and do them; and that you seek not after your own heart and your own eyes, which incline you to go astray ; That you may remember, and do all my command- 1 ments, and be holy to your God" (Num. 15:37-40). This text is climaxed by the commands to look upon the fringes, to remem- ber the commandments, and to do them. But, why and how do the fringes enable a person to become holy to your God ? The rabbinic interpretation and explication of these biblical verses and the disappearance of the tekhelet fringe will lead us to a rather surprising exposi- tion of talmudic mysticism. Our inquiry begins with a quote from T.B. Menahot 43b. The Talmud there first quotes from the biblical text in a Tannaitic source ( Baraita ), and then adds a critical point: "That you may look upon it and remember . and do them . Looking [upon it] leads to remembering [the commandments], and re- membering leads to doing them." This comment presumably relates to the issue of looking at the fringe in order to remember the commandments. -

Chassidus on the Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) VA’ES CHA NAN _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah Deciphered Messages The Torah tells us ( Shemos 19:19) that when the Jewish people gathered at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah , “Moshe spoke and Hashem answered him with a voice.” The Gemora (Berochos 45a) der ives from this pasuk the principle that that an interpreter should not speak more loudly than the reader whose words he is translating. Tosafos immediately ask the obvious question: from that pasuk we see actually see the opposite: that the reader should n ot speak more loudly than the interpreter. We know, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, that Moshe’s nevua (prophecy) was different from that of the other nevi’im (prophets) in that “the Shechina was speaking through Moshe’s throat”. This means that the interpretation of the nevuos of the other nevi’im is not dependent on the comprehension of the people who hear it. The nevua arrives in this world in the mind of the novi and passes through the filter of his perspectives. The resulting message is the essence of the nevua. When Moshe prophesied, however, it was as if the Shechina spoke from his throat directly to all the people on their particular level of understanding. Consequently, his nevuos were directly accessible to all people. In this sense then, Moshe was the rea der of the nevua , and Hashem was the interpreter. -

Lelov: Cultural Memory and a Jewish Town in Poland. Investigating the Identity and History of an Ultra - Orthodox Society

Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Item Type Thesis Authors Morawska, Lucja Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 03/10/2021 19:09:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/7827 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Lucja MORAWSKA Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and International Studies University of Bradford 2012 i Lucja Morawska Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Key words: Chasidism, Jewish History in Eastern Europe, Biederman family, Chasidic pilgrimage, Poland, Lelov Abstract. Lelov, an otherwise quiet village about fifty miles south of Cracow (Poland), is where Rebbe Dovid (David) Biederman founder of the Lelov ultra-orthodox (Chasidic) Jewish group, - is buried. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

Mattos Chassidus on the Massei ~ Mattos Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) MATTOS ~ MASSEI _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah – Mattos Keep Your Word The Torah states (30:3), “If a man takes a vow or swears an oath to G -d to establish a prohibition upon himself, he shall not violate his word; he shall fulfill whatever comes out of his mouth.” In relation to this passuk , the Midrash quotes from Tehillim (144:4), “Our days are like a fleeting shadow.” What is the connection? This can be explained, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, according to a Gemara ( Nedarim 10b), which states, “It is forbidden to say, ‘ Lashem korban , for G-d − an offering.’ Instead a person must say, ‘ Korban Lashem , an offering for G -d.’ Why? Because he may die before he says the word korban , and then he will have said the holy Name in vain.” In this light, we can understand the Midrash. The Torah states that a person makes “a vow to G-d.” This i s the exact language that must be used, mentioning the vow first. Why? Because “our days are like a fleeting shadow,” and there is always the possibility that he may die before he finishes his vow and he will have uttered the Name in vain. n Story The wood chopper had come to Ryczywohl from the nearby village in which he lived, hoping to find some kind of employment. -

Chassidus on the Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) SH EVI’I SHEL PESACH _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah Shevi’i Shel Pesach – Kerias Yam Suf Walking on Dry Land Even in the Sea “And Bnei Yisrael walked on dry land in the sea” (Shemos 14:29) How can you walk on dry land in the sea? The Noam Elimelech , in Likkutei Shoshana , explains this contradictory-sounding pasuk as follows: When Bnei Yisrael experienced the Exodus and the splitting of the sea, they witnessed tremendous miracles and unbelievable wonders. There are Tzaddikim among us whose h earts are always attuned to Hashem ’s wonders and miracles even on a daily basis; they see not common, ordinary occurrences – they see miracles and wonders. As opposed to Bnei Yisrael, who witnessed the miraculous only when they walked on dry land in the sp lit sea, these Tzaddikim see a miracle as great as the “splitting of the sea” even when walking on so -called ordinary, everyday dry land! Everything they experience and witness in the world is a miracle to them. This is the meaning of our pasuk : there are some among Bnei Yisrael who, even while walking on dry land, experience Hashem ’s greatness and awesome miracles just like in the sea! This is what we mean when we say that Hashem transformed the sea into dry land. Hashem causes the Tzaddik to witness and e xperience miracles as wondrous as the splitting of the sea, even on dry land, because the Tzaddik constantly walks attuned to Hashem ’s greatness and exaltedness. -

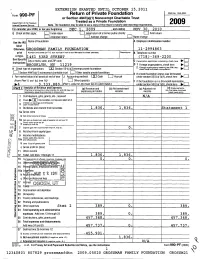

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

EXTENSION GRANTED UNTIL OCTOBER 15,2011 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF a or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2009 Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. For calendar year 2009, or tax year beginning DEC 1, 200 9 , and ending NOV 30, 2010 G Check all that apply: Initial return 0 Initial return of a former public charity LJ Final return n Amended return n Address chance n Name chance of foundation A Employer identification number Use the IRS Name label Otherwise , ROSSMAN FAMILY FOUNDATION 11-2994863 print Number and street (or P O box number if mad is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ortype. 1461 53RD STREET ( 718 ) -369-2200 See Specific City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exem p tion app lication is p endin g , check here 10-E] Instructions 0 1 BROOKLYN , NY 11219 Foreign organizations, check here ► 2. Foreign aanizations meeting % test, H Check type of organization. ®Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation chec here nd att ch comp t atiooe5 Section 4947(a )( nonexem pt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation 1 ) E If p rivate foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part Il, co! (c), line 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminatio n $ 3 , 333 , 88 0 .