How Corporations Have Influenced the U.S. Dialogue on Climate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Heartland Institute Under Attack Global Warming Fever Drives Scientists to Desperation

GREEN WATCH BANNER TO BE INSERTED HERE The Heartland Institute Under Attack Global Warming Fever Drives Scientists to Desperation By Matt Patterson Summary: It was Valentine’s Day, but it was no love letter. On February 14, 2012, renowned environmental scientist Peter Gleick transmitted to a group of liberal bloggers and journalists documents that he obtained from the Heartland Institute, a Chicago-based think-tank specializing in environmental policy. Gleick’s goal: destroy Heartland, a group that has mobilized scien- tists who are skeptical about global warm- ing. Gleick faked his identity and pretended to be a Heartland board member to obtain some of the documents. One of the docu- Dr. Peter Gleick - Thief ments that Gleick sent was a fake, created Yale and received his Ph.D. in Energy and social equity.” In 2010 the Pacifi c by Gleick or parties unknown to prove what and Resources from the University of Institute received more than $2.2 million wasn’t true. Gleick’s reckless, unethical and, California, Berkeley in 1986. He is in grants and contributions from a mix of most likely, criminal action shows just how currently president of the Pacifi c Institute foundations (e.g. Hewlett, Packard, Robert desperate green activists are to prop up their for Studies in Development, Environment, Wood Johnson, Rockefeller Brothers, overblown claims about global warming. and Security, which he co-founded in Rockefeller) and government agencies r. Peter Gleick was a trusted 1987. (e.g. Sacramento County and the Florida and respected scientist, with a Dcareer studded with honors and The Oakland, California-based research May 2012 awards. -

MAP Act Coalition Letter Freedomworks

April 13, 2021 Dear Members of Congress, We, the undersigned organizations representing millions of Americans nationwide highly concerned by our country’s unsustainable fiscal trajectory, write in support of the Maximizing America’s Prosperity (MAP) Act, to be introduced by Rep. Kevin Brady (R-Texas) and Sen. Mike Braun (R-Ind.). As we stare down a mounting national debt of over $28 trillion, the MAP Act presents a long-term solution to our ever-worsening spending patterns by implementing a Swiss-style debt brake that would prevent large budget deficits and increased national debt. Since the introduction of the MAP Act in the 116th Congress, our national debt has increased by more than 25 percent, totaling six trillion dollars higher than the $22 trillion we faced less than two years ago in July of 2019. Similarly, nearly 25 percent of all U.S. debt accumulated since the inception of our country has come since the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Now more than ever, it is critical that legislators take a serious look at the fiscal situation we find ourselves in, with a budget deficit for Fiscal Year 2020 of $3.132 trillion and a projected share of the national debt held by the public of 102.3 percent of GDP. While markets continue to finance our debt in the current moment, the simple and unavoidable fact remains that our country is not immune from the basic economics of massive debt, that history tells us leads to inevitable crisis. Increased levels of debt even before a resulting crisis slows economic activity -- a phenomenon referred to as “debt drag” -- which especially as we seek recovery from COVID-19 lockdowns, our nation cannot afford. -

Area Companies Offering Matching Gifts Below Is a Partial List of Area Companies Offering Matching Gifts

Area Companies Offering Matching Gifts Below is a partial list of area companies offering matching gifts. Please check to see if your employer is on the list and/or check with your company if they offer the program. If your employer offers a matching gift program, please request a matching gift form from your employer or fill out their online form. Matching gifts can be made to the Tredyffrin Township Libraries, Paoli Library or Tredyffrin Public Library. Aetna FMC Corporation PNC Financial Services AIG GATX PPG Industries Air Products and Chemicals, Inc. GE Foundation PQ Corporation Allstate Foundation GlaxoSmithKline Procter & Gamble Altria Group, Inc. Glenmede Prudential Financial American Express Company Hillman Company PVR Partners, L.P. American International Group, Inc. Houghton Mifflin Quaker Chemical Corporation AmeriGas Propane, Inc. IBM Corporation Quest Diagnostics AON J.P. Morgan Chase Ross Arkema Inc. John Hancock Saint-Gobain Corporation Automatic Data Processing Johnson & Johnson Sandmeyer Steel Company AXA Foundation, Inc. JP Morgan Chase SAP Matching Gift Program Axiom Data, Inc. Kaplan Inc. Schering-Plough Foundation Bank of America Kellogg Schroder Investment Management Bemis Company Foundation KPMG LLP Shell Oil Company Berwind Corporation Liberty Mutual State Farm Companies Foundation BlackRock Lincoln Financial Group Subaru of America Boeing Company May Department Stores Sun Life Financial BP McDonald's Sun Microsystems, Inc Bristol-Myers Squibb Company McKesson Foundation Sunoco, Inc. C. R. Bard, Inc. Merck & Co., Inc. Tenet Healthcare Foundation CertainTeed Merrill Lynch Texas Instruments Charles Schwab Merrill Lynch ACE INA Foundation Chevron Corporation Microsoft AXA Foundation Chubb Group of Insurance Companies Minerals Technologies Inc. Dow Chemical Company CIGNA Foundation Mobil Foundation Inc. -

Heartland Climate Economists List SAMPLE

U.S. Climate Economists Mailing List May 30, 2017 Name Contact Information Email Address Qualifications Anderson, Terry Property and Environment A founder of the Free Market Environmentalism, coauthor (with Leal) of the basic reference on the Research Center subject, head of PERC until just recently. See Anderson, T.L. and McChesney, F.S. 2003. Property Rights: Cooperation, Conflict, and Law . Princeton, MA: Princeton University Press. Suite A B.S. University of Montana, Ph.D. in economics from the University of Washington. Bozeman, MT Phone Ausubel, Jesse The Rockefeller University Director of the Program for the Human Environment and Senior Research Associate at The Rockefeller r.edu University in New York City. From 1977-1988 Mr. Ausubel worked for the National Academies complex in Washington DC as a fellow of the National Academy of Sciences, staff officer of the National Research New York, NY Council Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate, and from 1983-1988 Director of Programs for the National Academy of Engineering (NAE). Mr. Ausubel was a main organizer of the first UN World http://www.rockefeller.edu/ Climate Conference (Geneva, 1979), which substantially elevated the global warming issue on scientific research/faculty/researchaffi and political agendas. During 1979-1981 he led the Climate Task of the Resources and Environment liates/JesseAusubel/#conten Program of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, near Vienna, Austria, an East-West t think-tank created by the U.S. and Soviet academies of sciences. Mr. Ausubel helped formulate the US and world climate research programs. Ausubel is one of the top two or three authorities on how the environment is getting cleaner and safer overtime. -

Minimum Wage Coalition Letter Freedomworks

June 23, 2021 Dear Members of Congress, We, the undersigned organizations representing millions of Americans nationwide, write in blanket opposition to any increase in the federal minimum wage, especially in such a time when our job market needs maximum flexibility to recover from the havoc wreaked on it by the government's response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Workers must be compensated for their labor based on the value that said labor adds to their employer. Any deviation from this standard is harmful to workers and threatens jobs and employment opportunities for all workers. Whether it be to $11, $15, or any other dollar amount, increasing the federal minimum wage further takes away the freedom of two parties to agree on the value of one’s labor to the other’s product. As a result, employment options are restricted and jobs are lost. Instead, the free market should be left alone to work in the best interest of employers and employees alike. While proponents of raising the minimum wage often claim to be working in service of low-wage earners, studies have regularly shown that minimum wage increases harm low-skilled workers the most. Higher minimum wages inevitably lead to lay-offs and automation that drives low-skilled workers to unemployment. The Congressional Budget Office projected that raising the minimum wage to $15 would directly result in up to 2.7 million jobs lost by 2026. Raising it to $11 in the same time frame - as some Senators are discussing - could cost up to 490,000 jobs, if such a proposal is paired with eliminating the tip credit as well. -

Albert Jacobs

Climate Science Newsletters By: Albert Jacobs ___________________________________________________________________________ CliSci # 82 2011-12-21 Four Sceptic Scientists testify before the Canadian Senate Committee. The Senate Energy & Environment Committee Hearing with Drs. Ross McKitrick, Ian Clark, Jan Veizer and Tim Patterson took place on December 15th 2011. The video is now on YouTube at: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xW19pPFfIyg#t=65> ------------------------------ The COP 17 aftermath The conclusions of COP 17 are found on <http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2011//eng/l04.pdf> In the words of Kumi Naidoo, Greenpeace International Executive Director: “The grim news is that the blockers lead by the US have succeeded in inserting a vital get- out clause that could easily prevent the next big climate deal being legally binding. If that loophole is exploited it could be a disaster. And the deal is due to be implemented ‘from 2020′ leaving almost no room for increasing the depth of carbon cuts in this decade when scientists say we need emissions to peak,” “Right now the global climate regime amounts to nothing more than a voluntary deal that’s put off for a decade. This could take us over the two degree threshold where we pass from danger to potential catastrophe.” And on December 12th: <http://news.nationalpost.com/2011/12/12/canada-formally-withdrawig-from- kyoto-protocol/> Canada put a full stop after Jean Chrétien’s folly. We do not quote DeSmogBlog very often, but they seem to have blown their top: " Canada's decision to turn its back on its international obligations confirms yet again that Stephen Harper and his carbon cronies are securing a hellish future for generations to come. -

General Information - Automotive

Group 0 General Information - Automotive GENERAL: This group contains information applicable to all other groups. Such items as lubrication, trouble- shooting of entire coach, storage, towing, and a description of the part number structure used by the Recreational Vehicle Division are included. SPECIFICS: As applicable ...Cleaning of Coach ...Grouping Key ...Jacking of Coach ...Lubrication of Coach ...Parts Structure Key ...Parts Tables (bolts, screws, nuts, tubing, wire, etc. ) ...Preventive Maintenance ...Servicing of Coach ...Specifications of Coach ...Storage of Coach ...Table of Contents ...Tools and Equipment ...Towing of Coach ...Troubleshooting of Coach FMC Corporation Motor Coach Division HFMC 333 Brokaw Road Box 664 Santa Clara California 95052 REPAIR PARTS LIST GROUP. MODEL All GROUP 0 GENERAL INFORMATION SCOPE All repair parts will be shipped F.O.B., FMC/ MCD Santa Clara, California Plant. This Repair Parts Catalog lists all serviceable parts required for motor homes floor plans "A", NOTE "J" and "M" built by FMC/MCD. It is divided into functional groups as indicated on the frontis- Always provide model and serial num- piece of this catalog. The functional group ber of coach and, if applicable, model system used by FMC/MCD is designed to enable and serial number of component for you to quickly find and order repair parts for which part(s) is ordered. your coach. For example, Group 9 "Brakes- Service, " contains a complete listing of all EMERGENCY PARTS ORDER serviceable brake parts used throughout the coach whether applied to the front or the rear When ordering repair parts on an "Emergency" brakes. basis, call FMC/MCD after you have filled out the Parts Order form number RVD-67 (refer to PART NUMBERS instructions given below). -

FMC CORPORATION Annual Report 2003 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS

FMC CORPORATION Annual Report 2003 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS (In millions, except per share amounts) 2003 REVENUE 2003 OPERATING PROFIT BY SEGMENT BY SEGMENT Industrial Industrial Chemicals Agricultural Chemicals $770.6 $34.0 $82.0 Products $640.1 Agricultural Products $102.1 $515.8 Specialty Specialty Chemicals Chemicals 2003 2002 Revenue $ 1,921.4 $ 1,852.9 Segment operating profit (1) $ 218.1 $ 230.9 Income from continuing operations $ 39.8 $ 69.1 Earnings per share from continuing operations: Basic $ 1.13 $ 2.06 Diluted $ 1.12 $ 2.01 Other data Restructuring and other charges (gains) per share (2) $ 0.78 $ 0.55 Earnings per share from continuing operations before restructuring and other charges (gains): (1) Basic $ 1.92 $ 2.61 Diluted $ 1.90 $ 2.55 Capital expenditures $ 87.0 $ 83.9 Research and development expenses 87.4 82.0 Net debt (total debt less cash and restricted cash) 856.3 902.8 (1) Earnings per share from continuing operations, before restructuring and other charges (gains), and segment operating profit (consolidated), are not measures of financial performance under generally accepted accounting principles and should not be considered in isolation from, or as substitutes for, income from continuing operations, net income, or earnings per share determined in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles, nor as the sole measures of our profitability. (2) Restructuring and other charges (gains) includes FMC’s share of charges recorded by Astaris, LLC, the phosphorus joint venture. There were no significant Astaris-related restructuring charges recorded in 2002. TO OUR SHAREHOLDERS Bill Walter, chairman of the board, president and chief executive officer While we continued to face difficult conditions in several of our businesses in 2003, we were able to meet or exceed our near-term goals and continued to make progress toward our longer term strategic objectives. -

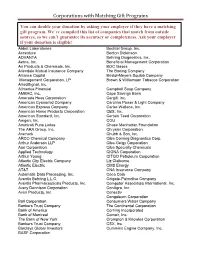

Corporations with Matching Gift Programs

Corporations with Matching Gift Programs You can double your donation by asking your employer if they have a matching gift program. We’ve compiled this list of companies that match from outside sources, so we can’t guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Ask your employer if your donation is eligible! Abbot Laboratories Bechtel Group, Inc. Accenture Becton Dickinson ADVANTA Behring Diagnostics, Inc. Aetna, Inc. Beneficial Management Corporation Air Products & Chemicals, Inc. BOC Gases Allendale Mutual Insurance Company The Boeing Company Alliance Capital Bristol-Meyers Squibb Company Management Corporation, LP Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation AlliedSignal, Inc. Allmerica Financial Campbell Soup Company AMBAC, Inc. Cape Savings Bank Amerada Hess Corporation Cargill, Inc. American Cyanamid Company Carolina Power & Light Company American Express Company Carter-Wallace, Inc. American Home Products Corporation CBS, Inc. American Standard, Inc. Certain Teed Corporation Amgen, Inc. CGU Ammirati Puris Lintas Chase Manhattan Foundation The ARA Group, Inc. Chrysler Corporation Aramark Chubb & Son, Inc. ARCO Chemical Company Ciba Corning Diagnostics Corp. Arthur Anderson LLP Ciba-Geigy Corporation Aon Corporation Ciba Specialty Chemicals Applied Technology CIGNA Corporation Arthur Young CITGO Petroleum Corporation Atlantic City Electric Company Liz Claiborne Atlantic Electric CMS Energy AT&T CNA Insurance Company Automatic Data Processing, Inc. Coca Cola Aventis Behring L.L.C. Colgate-Palmolive Company Aventis Pharmaceuticals Products, Inc. Computer Associates International, Inc. Avery Dennison Corporation ConAgra, Inc. Avon Products, Inc. Conectiv Congoleum Corporation Ball Corporation Consumers Water Company Bankers Trust Company The Continental Corporation Bank of America Corning Incorporated Bank of Montreal Comair, Inc. The Bank of New York Crompton & Knowles Corporation Bankers Trust Company CSX, Inc. -

Timothy F. Ball

Tags: Friends Of Science, Friends of Science, Natural Resource Stewardship Project, Nrsp, NRSP, Tim Ball, tim ball, timothy f ball, tom harris Timothy F. Ball Ball and the oil industry Ball is listed as a "consultant" of a Calgary-based global warming skeptic organization called the "Friends of Science" (FOS). Ball is also listed as an "Executive" for a Canadian group called the "Natural Resource Stewardship Project," (NRSP) a lobby organization that refuses to disclose its funding sources. DeSmog recently uncovered information showing that two of the founding directors of the NRSP are lobbyists for the energy sector. Ball and the oil industry In a January 28, 2007 article in the Toronto Star, the President of the Friends of Science admitted that about one-third of the funding for the FOS is provided by the oil industry. In an August 2006 Globe and Mail feature, FOS was exposed as being funded in part by the oil and gas sector and hiding this fact. According to the Globe and Mail, the oil industry money was funnelled through the Calgary Foundation charity to the University of Calgary and then put into an education trust for the FOS. Ball inflates credentials Ball and the organizations he is affiliated with have repeatedly made the claim that he is the "first Canadian PhD in climatology." Even further, Ball once claimed he was "one of the first climatology PhD's in the world." As many people have pointed out, there have been many PhD's in the field prior to Ball. Ball and the NRSP Ball is listed as an "Executive" for a Canadian group called the "Natural Resource Stewardship Project," (NRSP) a lobby organization that refuses to disclose its funding sources. -

Abbott Laboratories Advanced Micro Devices, Inc

FORTUNE 1000 CUSTOMERS equipped with the power to save lives 3M (3 Com Corporation) Gannett Co, Inc. Pittston Co 3M (3M Company) General Electric Pratt & Whitney Abbott Laboratories Gencorp Praxair Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. General Dynamics Corporation Procter & Gamble Agilent Technologies, Inc. General Mills Progressive Insurance AK Steel General Motors Purolator Alcoa Gillette Quantum Corporation Allstate Gold Kist, Inc. Raytheon Amazon Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. Readers Digest Amerada Hess Corporation Goodyear Reebok American Express Great Lakes Chemical Corp Revlon, Inc. Anadarko Petroleum Corporation Guidant Corporation Rockwell International AON Corporation Halliburton Company Rohm and Haas Company Apache Corporation Harley-Davidson Safeco Corporation Applied Materials Harris Corporation Sentry Insurance Ashland, Inc. Heinz Sherwin-Williams AT&T Hercules Incorporated Sierra Pacific Resources Ball Corporation Hewlett Packard Sisco Bank of America Corporation Hilton Spartan Stores Bank of New York Company, Inc. Hon Industries, Inc. Sprint Bear Stearns Companies, Inc. Honeywell Solectron Corporation Bethlehem Steel Hubbell Corporation Solutia, Inc. Blockbuster IBM Southern Company Boeing Intel Southern Union Company, Inc. Bristol-Myers Squibb International Paper Standard Register Company Cabot ITT Industries, Inc. State Farm Calpine Corporation Jabil Circuit, Inc. Steelcase, Inc. Carrier Corporation John Deere Textron, Inc. Caterpillar Johnson & Johnson The Gap Charter Communications, Inc. Johnson Controls Timberland Company Chevron -

Aligning For

FMC Corporation 2013 Annual Report FMC Corporation FMC Corporation 1735 Market Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 USA www.FMC.com ALIGNING FOR Portions of this publication are printed on recycled paper using soy-based inks. Copyright © 2014, FMC Corporation. All rights reserved. BOARD OF DIRECTORS EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OFFICERS Pierre R. Brondeau Pierre R. Brondeau Thomas C. Deas, Jr. President, Chief Executive Officer President, Chief Executive Officer Vice President and Treasurer and Chairman of the Board and Chairman of the Board LETTER TO SHAREHOLDERS FMC Corporation Marc L. Hullebroeck Paul Graves Vice President and Business Director Eduardo E. Cordeiro Executive Vice President FMC Agricultural Solutions, Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer North America and EMEA and Chief Financial Officer Throughout our more than 130-year history, FMC’s expected to deliver meaningful benefits to the separated Cabot Corporation Mark A. Douglas David A. Kotch President Vice President, Chief Information Officer success has been defined not only by its customer businesses, shareholders, customers, employees and G. Peter D’Aloia FMC Agricultural Solutions relationships, innovative products and financial other stakeholders, and the communities in which Managing Director Eric W. Norris and Member of the Board of Directors Edward T. Flynn Vice President, Global Business Director discipline, but also by a steadfast focus on future they operate. Ascend Performance Materials President Lithium opportunities. Last year was no exception. Holdings, Inc. FMC Minerals Nicholas L. Pfeiffer “FMC Minerals” will be a leading, structurally C. Scott Greer Mike Smith Corporate Controller Early in 2013, after another year of record sales advantaged minerals company and the largest global Principal Vice President, Global Business Director and earnings, we realigned reporting segments to producer of natural soda ash.