Maya Haptas Thesis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mellon Park City of Pittsburgh Historic Landmark Nomination

Mellon Park City of Pittsburgh Historic Landmark Nomination Prepared by Preservation Pittsburgh for Friends of Mellon Park 412.256.8755 1501 Reedsdale St., Suite 5003 September, 2020. Pittsburgh, PA 15233 www.preservationpgh.org HISTORIC REVIEW COMMISSION Division of Development Administration and Review City of Pittsburgh, Department of City Planning 200 Ross Street, Third Floor Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15219 INDIVIDUAL PROPERTY HISTORIC NOMINATION FORM Fee Schedule HRC Staff Use Only Please make check payable to Treasurer, City of Pittsburgh Date Received: .................................................. Individual Landmark Nomination: $100.00 Parcel No.: ........................................................ District Nomination: $250.00 Ward: ................................................................ Zoning Classification: ....................................... 1. HISTORIC NAME OF PROPERTY: Bldg. Inspector: ................................................. Council District: ................................................ Mellon Park 2. CURRENT NAME OF PROPERTY: Mellon Park 3. LOCATION a. Street: 1047 Shady Ave. b. City, State, Zip Code: Pittsburgh, Pa. 15232 c. Neighborhood: Shadyside/Point Breeze 4. OWNERSHIP d. Owner(s): City of Pittsburgh e. Street: 414 Grant St. f. City, State, Zip Code: Pittsburgh, Pa. 15219 Phone: (412) 255-2626 5. CLASSIFICATION AND USE – Check all that apply Type Ownership Current Use: Structure Private – home Park District Private – other Site Public – government Object Public - other Place of religious worship 1 6. NOMINATED BY: a. Name: Elizabeth Seamons for Friends of Mellon Park & Matthew Falcone of Preservation Pittsburgh b. Street: 1501 Reedsdale St. #5003 c. City, State, Zip: Pittsburgh, Pa. 15233 d. Phone: (412) 417-5910 Email: [email protected] 7. DESCRIPTION Provide a narrative description of the structure, district, site, or object. If it has been altered over time, indicate the date(s) and nature of the alteration(s). (Attach additional pages as needed) If Known: a. -

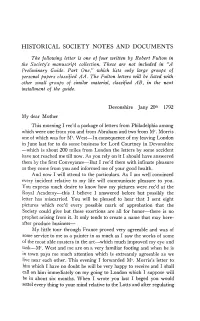

Other Small Groups of Similar Material, Classified AB, in the Next Installment of the Guide

HISTORICAL SOCIETY NOTES AND DOCUMENTS The following letter is one oj jour written by Robert Fulton in the Society's manuscript collection. These are not included in "A Preliminary Guide. Part One" which lists only large groups of personal papers classified AA. The Fulton letters willbe listed with other small groups of similar material, classified AB, in the next installment of the guide. Devonshire Jany 20th 1792 My dear Mother This morning Irec'd a package of letters from Philadelphia among which were one from you and from— Abraham and two from Mr.Morris one of which was for Mr.West Inconsequence of my leaving London —inJune last for to do some business for Lord Courtney inDevonshire which is about 200 miles from London the letters by some accident have not reached me tillnow.—As you rely on itIshould have answered them by the firstConveyance But Irec'd them with infinate pleasure as they come from you and informed me of your good health. And now Iwillattend to the particulars. As Iam well convinced every incident relative to my life will communicate pleasure to you. You express much— desire to know how my pictures were rec'd at the Royal Academy this Ibelieve Ianswered before but possibly the letter has miscarried. You willbe pleased to hear that Isent eight pictures which rec'd every possible mark of approbation— that the Society could give but these exertions are all for honor there is no prophet arising from it.Itonly tends to create a name that may here- after produce business — My little tour through France proved very agreeable and was of some service to me as a painter in—as much as Isaw the works of some of the—most able masters in the art which much improved my eye and task Mr. -

Find Patterson's Clothes Here

HOME E1P Herald-Post EDITION The Newspaper That Serves Its Readers PRICE FIVE CENTS DELIVERED B? CARRIER EL PASO, TEXAS, MONDAY, OCTOBER 28, 1957 300 PER WEEK ' VOL. LXXVII NO. 257 Puzzle Grows Find Patterson's Over Ouster Mystery Clothes Here OfZhukov Feeling Spreads That General's Removal Prowls Was Step Downward Bv Associated Press MOSCOW, Oct. 28.—The belief Is growing among Westerners in Moscow that Marshal George K. Zhukov's Another Home removal as defense minister means he has been downgraded and that Nikita Khrushchev sits j firmly in the Kremlin saddle. Intruder Soviet officialdom is stiH veiled ..: silence. Nothing specific has Program Of aec-n added to the terse, nine-line announcement Saturday that Zhu- Frightens •cov has been replaced by Marshal Radion Y. Malinovsky. Daniel Takes Most Western diplomats in Mos- cow believe that regardless of E. P. Woman whether Zhukov receives a new Believed To Be government post, Khrushchev's au- Whole Session iiority in the Kremlin is at least Chief Executive's 5 One Who Entered as strong as ever. Only One Effect Proposals to Take All Hervey Home They also believe that there will be no adverse reaction in the Time Allotted Solons The mysterious intruder country, no matter where Zhukov who has entered at least six turns up next. By ERNEST BAILEY homes recently, prowled One veteran western diplomat Herdd-foit Aailln Cormvondent AUSTIN, Oct. 28.—House again early today. said: He entered the Leon Siegel "TTie omission from the official Speaker Waggoner Carr to announcement of any indication home at 4228 Hampshire street day said he didn't know and was frightened away by their that the change was made to per- whether or not the Legisla- mit Zhukov's assignment to other ;ure can complete action on •creams. -

Pittsburgh, PA), Records, 1920-1993 (Bulk 1960-90)

Allegheny Conference On Community Development (Pittsburgh, PA), Records, 1920-1993 (bulk 1960-90) Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania Archives MSS# 285 377 boxes (Box 1-377); 188.5 linear feet Table of Contents Historical Note Page 2 Scope and Content Note Page 3 Series I: Annual Dinner Page 4 Series II: Articles Page 4 Series III: Community Activities Advisor Page 4 Series IV: Conventions Page 5 Series V: Director of Planning Page 5 Series VI: Executive Director Page 5 Series VII: Financial Records Page 6 Series VIII: Highland Park Zoo Page 6 Series IX: Highways Page 6 Series X: Lower Hill Redevelopment Page 6 Series XI: Mellon Square Park Page 7 Series XII: News Releases Page 7 Series XIII: Pittsburgh Bicentennial Association Page 7 Series XIV: Pittsburgh Regional Planning Association Page 7 Series XV: Point Park Committee Page 7 Series XVI: Planning Page 7 Series XVII: Recreation, Conservation and Park Council Page 8 Series XVIII: Report Library Page 8 Series XIX: Three Rivers Stadium Page 8 Series XX: Topical Page 8 Provenance Page 9 Restrictions and Separations Page 9 Container List Series I: Annual Dinner Page 10 Series II: Articles Page 13 Series III: Community Activities Advisor Page 25 Series IV: Conventions Page 28 Series V: Director of Planning Page 29 Series VI: Executive Director Page 31 Series VII: Financial Records Page 34 Series VIII: Highland Park Zoo Page 58 Series IX: Highways Page 58 Series X: Lower Hill Page 59 Series XI: Mellon Square Park Page 60 Series XII: News Releases Page 61 Allegheny Conference On Community -

Who Is Richard Mellon Scaife?

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 24, Number 16, April 11, 1997 Who is Richard Mellon Scaife? Part3 of our expose on the moneybags behind the media assault against President Clinton and Lyndon LaRouche. Edward Spannaus reports. A certain irony exists, in the fact of Richard Mellon Scaife's treated as a full-fledged Mellon. Dickie would later describe bankrolling of a network of anti-capitalist Mont Pelerin Soci his father as "sucking hind tit" to the Mellons. ety think-tanks in the U.S. The Mont Pelerin Society-the As he grew older, young Dickie became resentful of the modem-day embodiment of the feudal, aristocratic "Austrian treatment that his father had gotten at the hands of the Mel School" of monetarist economics-bitterly hates industrial Ions, and he often made his animosity known, particularly capitalism and any form of centralized, dirigist measures toward his uncle, Richard King Mellon. Dickie became through which a nation-state can build up its own industrial known as a "bull in a china shop." Some attributed his impetu technological base, while restricting access to predatory inter ousness to his being thrown by a horse at age 9; his skull was national financial looters. partially crushed, and was repaired with an aluminum plate The fact of the matter is that the Pittsburgh Scaife family and much plastic surgery. was a pioneering U.S. industrial family, especially in the 19th As soon as his father died in 1952, Dickie sold off the century. At one time, the family was wont to boast that the Scaife Company for one dollar. -

Mellon Park City of Pittsburgh Historic Landmark Nomination

Mellon Park City of Pittsburgh Historic Landmark Nomination Prepared by Preservation Pittsburgh for Friends of Mellon Park 412.256.8755 1501 Reedsdale St., Suite 5003 September, 2020. Pittsburgh, PA 15233 www.preservationpgh.org HISTORIC REVIEW COMMISSION Division of Development Administration and Review City of Pittsburgh, Department of City Planning 200 Ross Street, Third Floor Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15219 INDIVIDUAL PROPERTY HISTORIC NOMINATION FORM Fee Schedule HRC Staff Use Only Please make check payable to Treasurer, City of Pittsburgh Date Received: .................................................. Individual Landmark Nomination: $100.00 Parcel No.: ........................................................ District Nomination: $250.00 Ward: ................................................................ Zoning Classification: ....................................... 1. HISTORIC NAME OF PROPERTY: Bldg. Inspector: ................................................. Council District: ................................................ Mellon Park 2. CURRENT NAME OF PROPERTY: Mellon Park 3. LOCATION a. Street: 1047 Shady Ave. b. City, State, Zip Code: Pittsburgh, Pa. 15232 c. Neighborhood: Shadyside/Point Breeze 4. OWNERSHIP d. Owner(s): City of Pittsburgh e. Street: 414 Grant St. f. City, State, Zip Code: Pittsburgh, Pa. 15219 Phone: (412) 255-2626 5. CLASSIFICATION AND USE – Check all that apply Type Ownership Current Use: Structure Private – home Park District Private – other Site Public – government Object Public - other Place of religious worship 1 6. NOMINATED BY: a. Name: Elizabeth Seamans for Friends of Mellon Park & Matthew Falcone of Preservation Pittsburgh b. Street: 1501 Reedsdale St. #5003 c. City, State, Zip: Pittsburgh, Pa. 15233 d. Phone: (412) 417-5910 Email: [email protected] 7. DESCRIPTION Provide a narrative description of the structure, district, site, or object. If it has been altered over time, indicate the date(s) and nature of the alteration(s). (Attach additional pages as needed) If Known: a. -

Ulster Pennsylvania Ulster-Scots and &‘The Keystone State’ Ulster-Scots and ‘The Keystone State’

Ulster Pennsylvania Ulster-Scots and &‘the Keystone State’ Ulster-Scots and ‘the Keystone State’ Introduction The earliest Ulster-Scots emigrants to ‘the New World’ tended to settle in New England. However, they did not get on with the Puritans who controlled government there and whom they came to regard as worse than the Church of Ireland authorities they had left behind in Ulster. For example, when the Ulster-Scots settlers in Worcester, Massachusetts, tried to build a Presbyterian meeting house, their Puritan neighbours tore it down. Thus, future Ulster- Scots emigrant ships headed further south to Newcastle, Delaware, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, rather than the ports of New England. Pennsylvania was established by William Penn in 1682 with two objectives: to enrich himself and as a ‘holy experiment’ in establishing complete religious freedom, primarily for the benefit of his fellow Quakers. George Fox, the founder of the Quakers, had visited the region in 1672 and was mightily impressed. As the historian D.H. Fischer has observed in Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (New York, 1991): William Penn was a bundle of paradoxes - an admiral son’s who became a pacifist, an undergraduate at Oxford’s Christ Church who became a pious Quaker, a member of Lincoln’s Inn who became an advocate of arbitration, a Fellow of the Royal Society who despised pedantry, a man of property who devoted himself to the poor, a polished courtier who preferred the plain style, a friend of kings who became a radical Whig, and an English gentleman who became one of Christianity’s great spiritual leaders. -

"Poor" in the Modern Sense. the Elemental Needs of Food, Clothing, and Shelter Were Supplied Through the Family

THE PHILANTHROPIC TRADITION IN PITTSBURGH* STANTON BELFOUR rr*HE philanthropic tradition in Pittsburgh has its origin in the dual JL nature of the pioneer Americans of the late eighteenth century when the inhabitants of the western counties were first citizens of the Old West. Independent as these people were personally, they were de- pendent on those about them for help in harvest, in raising house- frames, and in illness. In this new country, the pioneers turned to neighbors for many offices and functions that are performed by govern- ment or specialists in riper communities. Just as isolation in American foreign policy is an authentic outcome of community isolation, so are the multitude of American relief organizations the descendants of primi- tive interdependence. Hence, the dual nature of the American: indi- vidualism and herd instinct, indifference and kindliness. The giving men do is a personal thing. But differences are rooted in religion, nationality, and economic levels. In addition, there have been historic shifts. A Glance at History Among primitive people there were no "poor" in the modern sense. The elemental needs of food, clothing, and shelter were supplied through the family. To belong to a numerous family was to have aid to dependent children, maternity benefits, unemployment insurance, home relief, medical care, fire insurance, an old age annuity, and free burial. Oriental peoples relied on family responsibility, whereas the Egyp- tians emphasized meeting destitute —needs. The Greek and early Roman concepts were radically different kindly acts "toward people/' not toward the poor. Giving was directed toward the state or a worthy citi- zen, rather than out of pity for the poor. -

Legendary Ladies Undercover Assignments in Places Like Roosevelt Which Appears on Every Dime

Mills, Pennsylvania. As a reporter for the known work, although not often attrib- move from Scotland to Pittsburgh where and at the Carnegie Internationals. Mary Pittsburgh. The Company, a vital cultural enduring words were her sketches of Museum, Car and Carriage Museum, Pittsburgh area, recognizing famous of the Junior Leagues of America. Kathryn was a divorcee and openly Pittsburgh Dispatch, she took on risky uted to her, is the portrait of Franklin D. they had relatives. After making a for- was a fierce advocate for education and force for 20 years, performed European middle-class life in idyllic, small-town Visitors’ Center and Museum Shop, MARTHA GRAHAM people, places, and events. A tablet in Mrs. Harry Darlington, Jr. was the enjoyed the expensive lifestyle her legendary ladies undercover assignments in places like Roosevelt which appears on every dime. tune in steel, Andrew founded the women’s rights. Seventeen of Mary’s works, such as Verdi’s Aida and La Traviata, “Old Chester,” and the adventures of Greenhouse, and The Café at the Frick. memory of Julia Hogg was dedicated on first president. Early efforts focused ministry afforded her. Nevertheless, sweatshops, slums, and jails. It was She was named a Distinguished Daughter Carnegie Institute of Technology (now works are part of the Carnegie Museum and African-American works, such as country parson Dr. Lavendar. Margaret It is Helen’s legacy to her hometown. June 10, 1941, on the 50th anniversary on volunteer work in hospitals, she was wildly popular, ministering George Madden, the managing editor of of Pennsylvania in 1993. Carnegie Mellon University), and the of Art’s permanent collection. -

Richard Mellon Scaife: Provide the Contras with Arms

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 24, Number 13, March 21, 1997 replied: "Oliver North was in charge of the Contras for Bush. Oliver North was not the architect of the Iran-Contra opera tion, only the messenger. However, make no mistake, he was the messenger for Bush. Bush recruited Panamanian pilots to Richard Mellon Scaife: provide the Contras with arms. Bush was the one to provide the list of Panamanian pilots who were working with the Who is he, really? U.S. government." And who were the Bush-picked pilots? As Noriega notes by Edward Spannaus in his memoirs, "The pilots included such men as Jorge Canal ias, Floyd Carlton Caceres, Cesar Rodriguez and TeofiloWat son, future cocaine traffickers transporting Contra weapons The following article will be continued in aforthcoming issue. in exchange for cocaine." EIR's September 1996 Special Report provided further He's considered the stupidest member of his extended family, background on some of these men: "American officials al and was kicked out of Yale, not once, but twice. He's a (sup ready knew that Carlton had been arrested on a drug flight in posedly recovered) alcoholic, as have been most members of Peru during the 1970s. Watson was employed by Diacsa, a the family. The kindest description of his personality is "dark Miami-based company owned by Carlton and convicted and mysterious." He is known for never looking his own drug-trafficker Alfredo Caballero, who had been contracted employees straight in the eye. to deliver 'humanitarian aid' to the Contras by the State De He has a long history of using the U.S.