WG Collingwood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lakes Tour 2015

A survey of the status of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2015 S.C. Maberly, M.M. De Ville, S.J. Thackeray, D. Ciar, M. Clarke, J.M. Fletcher, J.B. James, P. Keenan, E.B. Mackay, M. Patel, B. Tanna, I.J. Winfield Lake Ecosystems Group and Analytical Chemistry Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Lancaster UK & K. Bell, R. Clark, A. Jackson, J. Muir, P. Ramsden, J. Thompson, H. Titterington, P. Webb Environment Agency North-West Region, North Area History & geography of the Lakes Tour °Started by FBA in an ad hoc way: some data from 1950s, 1960s & 1970s °FBA 1984 ‘Tour’ first nearly- standardised tour (but no data on Chl a & patchy Secchi depth) °Subsequent standardised Tours by IFE/CEH/EA in 1991, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010 and most recently 2015 Seven lakes in the fortnightly CEH long-term monitoring programme The additional thirteen lakes in the Lakes Tour What the tour involves… ° 20 lake basins ° Four visits per year (Jan, Apr, Jul and Oct) ° Standardised measurements: - Profiles of temperature and oxygen - Secchi depth - pH, alkalinity and major anions and cations - Plant nutrients (TP, SRP, nitrate, ammonium, silicate) - Phytoplankton chlorophyll a, abundance & species composition - Zooplankton abundance and species composition ° Since 2010 - heavy metals - micro-organics (pesticides & herbicides) - review of fish populations Wastwater Ennerdale Water Buttermere Brothers Water Thirlmere Haweswater Crummock Water Coniston Water North Basin of Ullswater Derwent Water Windermere Rydal Water South Basin of Windermere Bassenthwaite Lake Grasmere Loweswater Loughrigg Tarn Esthwaite Water Elterwater Blelham Tarn Variable geology- variable lakes Variable lake morphometry & chemistry Lake volume (Mm 3) Max or mean depth (m) Mean retention time (day) Alkalinity (mequiv m3) Exploiting the spatial patterns across lakes for science Photo I.J. -

Timetable & Prices

Use an around the lake ticket to either relax and enjoy a round How to find us trip on the boat, or hop on and off the boat throughout the day at our jetties and catch a later sailing back using the same ticket. Coniston Cruises Red Route Northern Service We run 7 days a week on Map From Sat 10 March to Sunday 28 October A Coniston Dept. 10.45 11.45 12.45 1.45 3.00 3.55 4.40 Timetable & Prices Waterhead 10.50 11.50 12.50 1.50 3.05 4.00 4.45 Torver 11.05 12.05 1.05 2.05 3.20 4.15 5.00 Brantwood 11.20 12.20 1.20 2.20 3.35 4.30 5.15 NEW - WILD CAT ISLAND CRUISES Coniston Arr. 11.30 12.30 1.30 2.30 3.45 4.40 5.25 AThe 4.40 Sailing runs from 26 March - 30 September Fares: Adult £11.50, Child £5.75, Family (2 adults and 3 children) £26 Around the lake or hop on & off throughout the day - see above. Single fares available to various points around the lake. Please pay on boat. Yellow Route Wild Cat Island Cruise on Map Coniston Dept. 10.00 11.20 12.30 2.05 3.15 From Torver 10.10 11.30 12.40 2.15 3.25 Saturday Sunny Bank 10.25 11.45 12.55 2.30 3.40 24 March to Brantwood 10.50 12.10 1.20 2.55 4.05 Sunday Coniston Arr. -

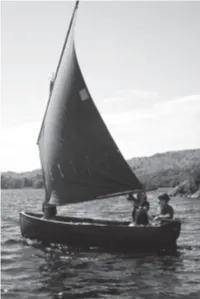

The Boats of Swallows and Amazons

The Boats of Swallows and Amazons Amazon on Coniston Contents Introduction The Swallow Rowing the Swallow Rigging the Swallow A letter from Roger Fothergill, an owner of the original Swallow Unknown Details The Amazon Sailing Performance Assesements Design Recommendations for new Swallows The Nancy Blackett and the Goblin The Best Boat? Design Recommendations for new Swallows Introduction What exactly were the Swallow and the Amazon like, those famous sailboats of Arthur Ransome's books Swallows and Amazons and Swallowdale? Many readers would love to recreate the adventures of the Walker and Blackett children for themselves, or for their own children, and they want to learn more about the boats. The boats of these special stories were real boats, just as many of the locations in the stories are real places. This essay describes what we know of the Swallow and the Amazon. In the summer of 1928, Ernest Altounyan, a friend of Arthur Ransome, came to Coniston Water with his family and soon thereafter bought two boats for his children. The children were Taqui (age eleven), Susan (age nine), Titty (age eight), Roger (age six), and Bridgit (nearly three). The children became the models for characters in Arthur Ransome's books, and the boats became the Swallow and Amazon. Susan and Roger crewed the Swallow, while Taqui and Titty crewed the Mavis, which was the model for the Amazon. The Mavis (Amazon), may be seen today, in good order, at the Windermere Steamboat Museum near Lake Windermere. When the Altounyans later moved to Syria, they gave the Swallow to Arthur Ransome, who lived at Low Ludderburn near Lake Windermere. -

A Survey of the Lakes of the English Lake District: the Lakes Tour 2010

Report Maberly, S.C.; De Ville, M.M.; Thackeray, S.J.; Feuchtmayr, H.; Fletcher, J.M.; James, J.B.; Kelly, J.L.; Vincent, C.D.; Winfield, I.J.; Newton, A.; Atkinson, D.; Croft, A.; Drew, H.; Saag, M.; Taylor, S.; Titterington, H.. 2011 A survey of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2010. NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, 137pp. (CEH Project Number: C04357) (Unpublished) Copyright © 2011, NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology This version available at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/14563 NERC has developed NORA to enable users to access research outputs wholly or partially funded by NERC. Copyright and other rights for material on this site are retained by the authors and/or other rights owners. Users should read the terms and conditions of use of this material at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/policies.html#access This report is an official document prepared under contract between the customer and the Natural Environment Research Council. It should not be quoted without the permission of both the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and the customer. Contact CEH NORA team at [email protected] The NERC and CEH trade marks and logos (‘the Trademarks’) are registered trademarks of NERC in the UK and other countries, and may not be used without the prior written consent of the Trademark owner. A survey of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2010 S.C. Maberly, M.M. De Ville, S.J. Thackeray, H. Feuchtmayr, J.M. Fletcher, J.B. James, J.L. Kelly, C.D. -

19. South Cumbria Low Fells Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 19. South Cumbria Low Fells Area profile: Supporting documents www.gov.uk/natural-england 1 National Character 19. South Cumbria Low Fells Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper 1, Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention3, we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are North areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines East in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. Yorkshire & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform West their decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a East landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage Midlands broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will West also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Midlands East of Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape England our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics London and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are South East suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance South West on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. -

The Rise and Fall of Anglo-Saxon Runic Stone Monuments Runic Inscriptions and the Development of Sculpture in Early Medieval England

Runrön Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet 24 Kopár, Lilla, 2021: The Rise and Fall of Anglo-Saxon Runic Stone Monu- ments. Runic Inscriptions and the Development of Sculpture in Early Medi- eval England. In: Reading Runes. Proceedings of the Eighth International Sym posium on Runes and Runic Inscriptions, Nyköping, Sweden, 2–6 September 2014. Ed. by MacLeod, Mindy, Marco Bianchi and Henrik Williams. Uppsala. (Run rön 24.) Pp. 143–156. DOI: 10.33063/diva-438873 © 2021 Lilla Kopár (CC BY) LILLA KOPÁR The Rise and Fall of Anglo-Saxon Runic Stone Monuments Runic Inscriptions and the Development of Sculpture in Early Medieval England Abstract The Old English runic corpus contains at least thirty-seven inscriptions carved in stone, which are concentrated geographically in the north of England and dated mainly from the seventh to the ninth centuries. The quality and content of the inscriptions vary from simple names (or frag- ments thereof) to poetic vernacular memorial formulae. Nearly all of the inscriptions appear on monumental sculpture in an ecclesiastical context and are considered to have served commemor- ative purposes. Rune-inscribed stones show great variety in terms of monument type, from name-stones, cross-shafts and slabs to elaborate monumental crosses that served different func- tions and audiences. Their inscriptions have often been analyzed by runologists and epigraphers from a linguistic or epigraphic point of view, but the relationship of these inscribed monuments to other sculptured stones has received less attention in runological circles. Thus the present article explores the place and development of rune-inscribed monuments in the context of sculp- tural production in pre-Conquest England, and identifies periods of innovation and change in the creation and function of runic monuments. -

Charr (Sal Velinus Alpinus L.) from Three Cumbrian Lakes

Heredity (1984), 53 (2), 249—257 1984. The Genetical Society of Great Britain BIOCHEMICALPOLYMORPHISM IN CHARR (SAL VELINUS ALPINUS L.) FROM THREE CUMBRIAN LAKES A. R. CHILD Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Directorate of Fisheries Research, Fisheries Laboratory, Pake field Road, Lowestoft, Suffolk NR33 OHT, U.K. Received25.i.84 SUMMARY Blood sera from four populations of charr (Salvelinus alpinus L.) inhabiting three lakes in Cumbria were analysed for genetic polymorphisms. Evidence was obtained at the esterase locus supporting the genetic isolation of two temporally distinct spawning populations of charr in Windermere. Significant differences at the transferrin and esterase loci between the Coniston population of charr and the populations found in Ennerdale Water and Windermere were thought to be due to genetic drift following severe reduction in the effective population size in Coniston water. 1. INTRODUCTION The Arctic charr (Salvilinus alpinus L.) has a circumpolar distribution in the northern hemisphere. The populations in the British Isles are confined to isolated lakes in Wales, Cumbria, Ireland and Scotland. Charr north of latitude 65°N are anadromous but this behaviour has been lost in southerly populations. This paper describes an investigation of biochemical polymorphism of the isozyme products of two loci, serum transferrin and serum esterase, in charr populations from three Cumbrian lakes—Windermere, Ennerdale Water and Coniston Water (fig. 1). Electrophoretic methods applied to tissue extracts have been employed by several workers in an attempt to clarify the "species complex" in Sal- velinus alpinus and to investigate interrelationships between charr popula- tions (Nyman, 1972; Henricson and Nyman, 1976; Child, 1977; Klemetsen and Grotnes, 1980). -

Doorway to Devotion: Recovering the Christian Nature of the Gosforth Cross

religions Article Doorway to Devotion: Recovering the Christian Nature of the Gosforth Cross Amanda Doviak Department of History of Art, University of York, York YO10 5DD, UK; [email protected] Abstract: The carved figural program of the tenth-century Gosforth Cross (Cumbria) has long been considered to depict Norse mythological episodes, leaving the potential Christian iconographic import of its Crucifixion carving underexplored. The scheme is analyzed here using earlier ex- egetical texts and sculptural precedents to explain the function of the frame surrounding Christ, by demonstrating how icons were viewed and understood in Anglo-Saxon England. The frame, signifying the iconic nature of the Crucifixion image, was intended to elicit the viewer’s compunction, contemplation and, subsequently, prayer, by facilitating a collapse of time and space that assim- ilates the historical event of the Crucifixion, the viewer’s present and the Parousia. Further, the arrangement of the Gosforth Crucifixion invokes theological concerns associated with the veneration of the cross, which were expressed in contemporary liturgical ceremonies and remained relevant within the tenth-century Anglo-Scandinavian context of the monument. In turn, understanding of the concerns underpinning this image enable potential Christian symbolic significances to be suggested for the remainder of the carvings on the cross-shaft, demonstrating that the iconographic program was selected with the intention of communicating, through multivalent frames of reference, the significance of Christ’s Crucifixion as the catalyst for the Second Coming. Keywords: sculpture; art history; archaeology; early medieval; Anglo-Scandinavian; Vikings; iconog- raphy Citation: Doviak, Amanda. 2021. Doorway to Devotion: Recovering the Christian Nature of the Gosforth Cross. -

Anglo-Saxon Sculpture and Rome: Perspectives and Interpretations

258 CHAPTER 6 Anglo-Saxon Sculpture and Rome: Perspectives and Interpretations Having seen the many and varied ways in which early Christian Anglo-Saxon architecture could articulate ideas of 'Rome', this chapter will turn to review the other public art form of the Anglo-Saxon landscape, the stone sculpture, to consider also its relationship with concepts of ‘Romanness’. This is an aspect that has emerged – more or less tangentially – from other scholarly analyses of the material, but it has not been used as a common denominator to interpret and understand Anglo-Saxon sculpture in its own right. In the course of the twentieth century, scholars from different disciplines have developed research questions often strictly related to their own circumstantial agendas or concerns when discussing this kind of material, and this has tended to affect and limit the information that could be gained. It is only recently that some more interdisciplinary approaches have been suggested which provide a fuller understanding of the artistic and cultural achievement conveyed through Anglo-Saxon sculpture. 6.1 The scholarship 6.1 a) Typology and Style1 Any discussion of Anglo-Saxon sculpture opens with an account of the work of W.G. Collingwood (1854-1932) 2 and the impact that it has had on the development of subsequent studies.3 As such, he is generally considered to have 1 For a recent and full discussion on the subject see the forthcoming work by A. Denton, An Anglo-Saxon Theory of Style: motif, mode and meaning in the art of eighth-century Northumbria (PhD, York, 2011); I am grateful to her for the chance of reading and discussing her work. -

Boofi 6HEEH SIATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY I

RUNIC EVIDENCE OF LAMINOALVEOLAR AFFRICATION IN OLD ENGLISH Tae-yong Pak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 1969 Approved by Doctoral Committee BOOfi 6HEEH SIATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY I 428620 Copyright hy Tae-yong Pak 1969 ii ABSTRACT Considered 'inconsistent' by leading runologists of this century, the new Old English runes in the palatovelar series, namely, gar, calc, and gar-modified (various modi fications of the old gifu and cën) have not been subjected to rigorous linguistic analysis, and their relevance to Old English phonology and the study of Old English poetry has remained unexplored. The present study seeks to determine the phonemic status of the new runes and elucidate their implications to alliteration. To this end the following methods were used: 1) The 60-odd extant Old English runic texts were examined. Only four monuments (Bewcastle, Ruthwell, Thornhill, and Urswick) were found to use the new runes definitely. 2) In the four texts the words containing the new and old palatovelar runes were isolated and tabulated according to their environments. The pattern of distribution was significant: gifu occurred thirteen times in front environments and twice in back environments; cen, eight times front and once back; gar, nine times back; calc, five times back and once front; and gar-modified, twice front. Although cen and gifu occurred predominantly in front environments, and calc and gar in back environments, their occurrences were not complementary. 3) To interpret the data minimal or near minimal pairs with the palatovelar consonants occurring in front or back environments were examined. -

The Making of Swallows & Amazons

chapter four The Amazons Attack My father said that his first impression of the film crew was ‘What an awful mess of trucks and weird people!’ He’d just come from his office in the electronics industry where everybody drove smart cars and wore suits with neat ties. Dad didn’t even own a pair of denim jeans, let alone purple bell-bottoms. One of The Arthur Ransome Society members took one look at his footage of the making of Swallows & Amazons and said, ‘It looks like Woodstock.’ Woodstock on wheels, except that unlike a music festival everyone had to keep quiet when filming was in progress. The notion of ‘Free Love’ was virtually typed on the Call Sheet. Goodness knows what the crew got up to in Ambleside. None of the men on the crew wore peace pendants, or behaved like Dylan the Rabbit from The Magic Roundabout, but they smoked cigarettes continuously. We children were all staunchly anti-smoking, particularly Sten, whose father had a ‘No Smoking’ sign on the front door of their house in Whiteway – even though it happened to be called Lucifer Lodge. Kit showed us how to sabotage a cigarette. We would use the tweezers on her Swiss Army knife to remove a bit of tobacco from the end, and would insert an unlit match-head before stuffing the tobacco back inside. The cigarette would then be returned to the victim’s packet. Soon after the cigarette was lit and a good smoke was being enjoyed, the match-head would suddenly ignite and flare up, terrifying everyone in the vicinity. -

The Anglo-Saxon Cross at St. Andrew, Auckland: 'Living Stones'

1 The Anglo-Saxon Cross at St. Andrew, Auckland: ‘Living Stones’. Nina Maleczek Abstract The remains of the High Cross at Auckland St. Andrews are well-known, but little documented. Rosemary Cramp1 describes and dates the cross (to between the end of the eighth-century and the beginning of the ninth), and while it is referred to in the work of Collingwood2, Coatsworth3 and others, it cannot boast the extensive study that sculptures such as the Ruthwell, Bewcastle and Rothbury crosses have received. The main reason for this seems to lie in the apparent simplicity of its figural scenes. However, by examining the St. Andrews cross in relation to other contemporary sculptures, by reassessing its figural scenes, and by questioning its function within the context of its religious and natural landscapes, it becomes clear that the cross does present an overall, coherent theme, which reflects the religious climate during which it was created, and which could even be connected to its function. In the course of this essay I hope to argue against a relatively simplistic reading of the cross’s figural scenes, and show instead that they are intimately linked to contemporary scriptural exegesis, issues regarding the role of the apostles in teaching and baptism, and the ecclesiastical relationship between late eighth-century England and the Papacy. 1 Cramp, R, Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture, (Oxford, 1984), pp.37-40. 2 Collingwood, Northumbrian Crosses of the pre-Norman age, (London, 1927), pp.114-19. 3 See Cramp (1984), p.39. 2 Introduction That stone crosses were being erected across the English landscape following the Synod of Whitby has been interpreted by Lang4 as a form of ecclesiastic propaganda, designed to show the Anglo-Saxon Church’s allegiance to the Papacy and its perceived foundation by St.