The Ancient Ironworks of Coniston Lake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lakes Tour 2015

A survey of the status of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2015 S.C. Maberly, M.M. De Ville, S.J. Thackeray, D. Ciar, M. Clarke, J.M. Fletcher, J.B. James, P. Keenan, E.B. Mackay, M. Patel, B. Tanna, I.J. Winfield Lake Ecosystems Group and Analytical Chemistry Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Lancaster UK & K. Bell, R. Clark, A. Jackson, J. Muir, P. Ramsden, J. Thompson, H. Titterington, P. Webb Environment Agency North-West Region, North Area History & geography of the Lakes Tour °Started by FBA in an ad hoc way: some data from 1950s, 1960s & 1970s °FBA 1984 ‘Tour’ first nearly- standardised tour (but no data on Chl a & patchy Secchi depth) °Subsequent standardised Tours by IFE/CEH/EA in 1991, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010 and most recently 2015 Seven lakes in the fortnightly CEH long-term monitoring programme The additional thirteen lakes in the Lakes Tour What the tour involves… ° 20 lake basins ° Four visits per year (Jan, Apr, Jul and Oct) ° Standardised measurements: - Profiles of temperature and oxygen - Secchi depth - pH, alkalinity and major anions and cations - Plant nutrients (TP, SRP, nitrate, ammonium, silicate) - Phytoplankton chlorophyll a, abundance & species composition - Zooplankton abundance and species composition ° Since 2010 - heavy metals - micro-organics (pesticides & herbicides) - review of fish populations Wastwater Ennerdale Water Buttermere Brothers Water Thirlmere Haweswater Crummock Water Coniston Water North Basin of Ullswater Derwent Water Windermere Rydal Water South Basin of Windermere Bassenthwaite Lake Grasmere Loweswater Loughrigg Tarn Esthwaite Water Elterwater Blelham Tarn Variable geology- variable lakes Variable lake morphometry & chemistry Lake volume (Mm 3) Max or mean depth (m) Mean retention time (day) Alkalinity (mequiv m3) Exploiting the spatial patterns across lakes for science Photo I.J. -

Timetable & Prices

Use an around the lake ticket to either relax and enjoy a round How to find us trip on the boat, or hop on and off the boat throughout the day at our jetties and catch a later sailing back using the same ticket. Coniston Cruises Red Route Northern Service We run 7 days a week on Map From Sat 10 March to Sunday 28 October A Coniston Dept. 10.45 11.45 12.45 1.45 3.00 3.55 4.40 Timetable & Prices Waterhead 10.50 11.50 12.50 1.50 3.05 4.00 4.45 Torver 11.05 12.05 1.05 2.05 3.20 4.15 5.00 Brantwood 11.20 12.20 1.20 2.20 3.35 4.30 5.15 NEW - WILD CAT ISLAND CRUISES Coniston Arr. 11.30 12.30 1.30 2.30 3.45 4.40 5.25 AThe 4.40 Sailing runs from 26 March - 30 September Fares: Adult £11.50, Child £5.75, Family (2 adults and 3 children) £26 Around the lake or hop on & off throughout the day - see above. Single fares available to various points around the lake. Please pay on boat. Yellow Route Wild Cat Island Cruise on Map Coniston Dept. 10.00 11.20 12.30 2.05 3.15 From Torver 10.10 11.30 12.40 2.15 3.25 Saturday Sunny Bank 10.25 11.45 12.55 2.30 3.40 24 March to Brantwood 10.50 12.10 1.20 2.55 4.05 Sunday Coniston Arr. -

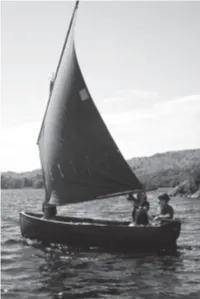

The Boats of Swallows and Amazons

The Boats of Swallows and Amazons Amazon on Coniston Contents Introduction The Swallow Rowing the Swallow Rigging the Swallow A letter from Roger Fothergill, an owner of the original Swallow Unknown Details The Amazon Sailing Performance Assesements Design Recommendations for new Swallows The Nancy Blackett and the Goblin The Best Boat? Design Recommendations for new Swallows Introduction What exactly were the Swallow and the Amazon like, those famous sailboats of Arthur Ransome's books Swallows and Amazons and Swallowdale? Many readers would love to recreate the adventures of the Walker and Blackett children for themselves, or for their own children, and they want to learn more about the boats. The boats of these special stories were real boats, just as many of the locations in the stories are real places. This essay describes what we know of the Swallow and the Amazon. In the summer of 1928, Ernest Altounyan, a friend of Arthur Ransome, came to Coniston Water with his family and soon thereafter bought two boats for his children. The children were Taqui (age eleven), Susan (age nine), Titty (age eight), Roger (age six), and Bridgit (nearly three). The children became the models for characters in Arthur Ransome's books, and the boats became the Swallow and Amazon. Susan and Roger crewed the Swallow, while Taqui and Titty crewed the Mavis, which was the model for the Amazon. The Mavis (Amazon), may be seen today, in good order, at the Windermere Steamboat Museum near Lake Windermere. When the Altounyans later moved to Syria, they gave the Swallow to Arthur Ransome, who lived at Low Ludderburn near Lake Windermere. -

A Survey of the Lakes of the English Lake District: the Lakes Tour 2010

Report Maberly, S.C.; De Ville, M.M.; Thackeray, S.J.; Feuchtmayr, H.; Fletcher, J.M.; James, J.B.; Kelly, J.L.; Vincent, C.D.; Winfield, I.J.; Newton, A.; Atkinson, D.; Croft, A.; Drew, H.; Saag, M.; Taylor, S.; Titterington, H.. 2011 A survey of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2010. NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, 137pp. (CEH Project Number: C04357) (Unpublished) Copyright © 2011, NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology This version available at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/14563 NERC has developed NORA to enable users to access research outputs wholly or partially funded by NERC. Copyright and other rights for material on this site are retained by the authors and/or other rights owners. Users should read the terms and conditions of use of this material at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/policies.html#access This report is an official document prepared under contract between the customer and the Natural Environment Research Council. It should not be quoted without the permission of both the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and the customer. Contact CEH NORA team at [email protected] The NERC and CEH trade marks and logos (‘the Trademarks’) are registered trademarks of NERC in the UK and other countries, and may not be used without the prior written consent of the Trademark owner. A survey of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2010 S.C. Maberly, M.M. De Ville, S.J. Thackeray, H. Feuchtmayr, J.M. Fletcher, J.B. James, J.L. Kelly, C.D. -

19. South Cumbria Low Fells Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 19. South Cumbria Low Fells Area profile: Supporting documents www.gov.uk/natural-england 1 National Character 19. South Cumbria Low Fells Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper 1, Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention3, we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are North areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines East in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. Yorkshire & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform West their decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a East landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage Midlands broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will West also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Midlands East of Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape England our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics London and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are South East suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance South West on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. -

Charr (Sal Velinus Alpinus L.) from Three Cumbrian Lakes

Heredity (1984), 53 (2), 249—257 1984. The Genetical Society of Great Britain BIOCHEMICALPOLYMORPHISM IN CHARR (SAL VELINUS ALPINUS L.) FROM THREE CUMBRIAN LAKES A. R. CHILD Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Directorate of Fisheries Research, Fisheries Laboratory, Pake field Road, Lowestoft, Suffolk NR33 OHT, U.K. Received25.i.84 SUMMARY Blood sera from four populations of charr (Salvelinus alpinus L.) inhabiting three lakes in Cumbria were analysed for genetic polymorphisms. Evidence was obtained at the esterase locus supporting the genetic isolation of two temporally distinct spawning populations of charr in Windermere. Significant differences at the transferrin and esterase loci between the Coniston population of charr and the populations found in Ennerdale Water and Windermere were thought to be due to genetic drift following severe reduction in the effective population size in Coniston water. 1. INTRODUCTION The Arctic charr (Salvilinus alpinus L.) has a circumpolar distribution in the northern hemisphere. The populations in the British Isles are confined to isolated lakes in Wales, Cumbria, Ireland and Scotland. Charr north of latitude 65°N are anadromous but this behaviour has been lost in southerly populations. This paper describes an investigation of biochemical polymorphism of the isozyme products of two loci, serum transferrin and serum esterase, in charr populations from three Cumbrian lakes—Windermere, Ennerdale Water and Coniston Water (fig. 1). Electrophoretic methods applied to tissue extracts have been employed by several workers in an attempt to clarify the "species complex" in Sal- velinus alpinus and to investigate interrelationships between charr popula- tions (Nyman, 1972; Henricson and Nyman, 1976; Child, 1977; Klemetsen and Grotnes, 1980). -

The Making of Swallows & Amazons

chapter four The Amazons Attack My father said that his first impression of the film crew was ‘What an awful mess of trucks and weird people!’ He’d just come from his office in the electronics industry where everybody drove smart cars and wore suits with neat ties. Dad didn’t even own a pair of denim jeans, let alone purple bell-bottoms. One of The Arthur Ransome Society members took one look at his footage of the making of Swallows & Amazons and said, ‘It looks like Woodstock.’ Woodstock on wheels, except that unlike a music festival everyone had to keep quiet when filming was in progress. The notion of ‘Free Love’ was virtually typed on the Call Sheet. Goodness knows what the crew got up to in Ambleside. None of the men on the crew wore peace pendants, or behaved like Dylan the Rabbit from The Magic Roundabout, but they smoked cigarettes continuously. We children were all staunchly anti-smoking, particularly Sten, whose father had a ‘No Smoking’ sign on the front door of their house in Whiteway – even though it happened to be called Lucifer Lodge. Kit showed us how to sabotage a cigarette. We would use the tweezers on her Swiss Army knife to remove a bit of tobacco from the end, and would insert an unlit match-head before stuffing the tobacco back inside. The cigarette would then be returned to the victim’s packet. Soon after the cigarette was lit and a good smoke was being enjoyed, the match-head would suddenly ignite and flare up, terrifying everyone in the vicinity. -

Windermere Management Strategy 2011 Lake District National Park

Windermere Management Strategy 2011 Lake District National Park With its world renowned landscape, the National Park is for everyone to enjoy, now and in the future. It wants a prosperous economy, world class visitor experiences and vibrant communities, to sustain the spectacular landscape. Everyone involved in running England’s largest and much loved National Park is committed to: • respecting the past • caring for the present • planning for the future Lake District National Park Authority Murley Moss Oxenholme Road Kendal Cumbria LA9 7RL Phone: 01539 724555 Fax: 01539 740822 Minicom: 01539 792690 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lakedistrict.gov.uk Alternative formats can be sent to you. Call 01539 724555 Publication number 07/11/LDNPA/100 Printed on recycled paper Photographs by: Ben Barden, Karen Barden, Chris Brammall, Val Corbett, Cumbria Tourism, John Eveson, Charlie Hedley, Andrea Hills, Si Homfray, LDNPA, Keith Molloy, Helen Reynolds, South Windermere Sailing Club, Phil Taylor, Peter Truelove, Michael Turner, Tony West, Dave Willis. Contents Introduction Introduction 2 National Park Purposes 3 National Park Vision 3 South Lakeland District Council Vision 4 Section A A1 Current context 9 A Prosperous A2 Challenges and opportunities 2011 11 Economy A3 Recent successes 13 A4 What we are going to do 13 Section B B1 Current context 16 World Class B2 Challenges and opportunities 2011 21 Visitor Experience B3 Recent success 22 B4 What we are going to do 23 Section C Traffic and Transport C1 Current context 27 Vibrant C2 Challenges -

Urbrainy.Com Worksheet

Distances in kilometres (1) Maths worksheets from urbrainy.com Rochester Castle Turtle Tours 75 km 49.5 km 77 km Bodiam Castle Lewes Castle 18.5 km 65.5 km Dover Castle 47 km (not drawn to scale) Hastings Castle Tommy Turtle is taking the rats on a tour of some of Southern England’s most famous castles. The measurements are in kilometres. 1. How far is it from Lewes Castle to Bodiam Castle via the shortest route? 2. How far is it from Bodiam Castle to Rochester Castle via Dover Castle? 3. Tommy’s bus goes on a speedy tour from Lewes Castle to Hastings Castle and then onto Bodiam Castle for lunch before visiting Rochester Castle and finishing at Dover Castle in the afternoon. How far did the bus travel? 4. Tommy left Dover Castle to drive the rats back to Lewes Castle by the shortest route. How many kilometres was this? Name: Page 1 © URBrainy.com some images © Graphics Factory.com Distances in kilometres (1) Maths worksheets from urbrainy.com Lyme Park Turtle Tours 43 km Chatsworth 31.5 km 12 km Haddon Hall Hardwick Hall 51 km 34.5 km 24.5 km (not drawn to scale) Tissington Hall Tommy Turtle is taking the rats on a tour of historic houses in and around the Peak District. The measurements are in kilometres. 1. How far is it from Lyme Park to Haddon Hall via Chatsworth? 2. How far is it from Tissington Hall to Hardwick Hall via Haddon Hall and Chatsworth? 3. Tommy drove the rats from Lyme Park to Tissington Hall and then onto Chatsworth via Haddon Hall. -

The Heart of Lakeland

TOUR 21 The Heart of Lakeland Leave the soft red sandstones of Carlisle and the Eden Valley to weave through hills of volcanic rocks and lakes carved out during the last Ice Age, before heading into the Pennines, with their different, gentler beauty. ITINERARY CARLISLE Ǡ Caldbeck (13m-21km) GRASMERE Ǡ Ambleside (4m-6.5km) CALDBECK Ǡ Bassenthwaite AMBLESIDE Ǡ Coniston (7m-11km) (9m-14.5km) CONISTON Ǡ Bowness (10m-16km) BASSENTHWAITE Ǡ Buttermere BOWNESS Ǡ Patterdale (13m-21km) (20m-32km) PATTERDALE Ǡ Penrith (14m-23km) BUTTERMERE Ǡ Keswick (13m-21km) PENRITH Ǡ Haltwhistle (34m-55km) KESWICK Ǡ Grasmere (15m-24km) HALTWHISTLE Ǡ Carlisle (23m-37km) 2 DAYS ¼ 175 MILES ¼ 282KM GLASGOW Birdoswald hing Irt Hadrian's ENGLAND B6318 Wall HOUSESTEADS A6 A69 A 07 Greenhead 7 1 4 9 Haltwhistle Ede A6 n Brampton 11 A 9 6 A6 8 9 CARLISLE Jct 43 Knarsdale 5 9 9 9 Eden 5 2 A Slaggyford S A 5 6 A Tyne B 6 8 Dalston 9 South Tynedale A689 Railway B Alston 53 Welton Pe 05 t te r i B l 52 M 99 6 Caldbeck Eden Ostrich A Uldale 1 World Melmerby 59 6 1 A w 8 6 6 A B5291 2 lde Ca Langwathby Cockermouth Bassenthwaite Penrith A Bassenthwaite 10 A A6 66 6 Lake 6 6 931m Wh A A66 inla 5 Skiddaw Pas tte 91 M Brougham Castle Low s r 2 6 66 9 A 2 5 6 2 Lorton A A B5292 3 4 5 Aira B B 5 Force L 2 Keswick o 8 Derwent Ullswater w 9 t Crummock Water e h l e Water a Glenridding r Buttermere d Thirlmere w o Patterdale 3 r 950m Buttermere r o Helvellyn 9 B Honister A 5 Pass 9 Rydal Kirkstone 1 5 Mount Pass Haweswater A Grasmere 5 9 2 Ambleside Stagshaw 6 Lake District National 3 59 Park Visitor Centre A Hawkshead Windermere Coniston 85 B52 8 7 0 10 miles Bowness-on-Windermere Near Sawrey 0 16 km Coniston Windermere 114 Water _ Carlisle Visitor Centre, Old Town Leave Bassenthwaite on Crummock Water, Buttermere Hall, Green Market, Carlisle unclassified roads towards the B5291 round the northern E Keswick, Cumbria Take the B5299 south from shores of the lake, then take The capital of the northern Lake Carlisle to Caldbeck. -

TRIP NOTES for Big Lakes Eight

TRIP NOTES for Big Lakes Eight This is a great way to see the entire Lake District National Derwent Water Park, from the perspective of the water itself as we undertake Derwent Water is fed by the River Derwent with a catchment a week of “lake bagging” by swimming across eight of the area in the high fells at the head of Borrowdale. It has a long biggest lakes. historical and literary background. Beatrix Potter sourced much material for her work from this Water. We swim across Windermere, Coniston Water, Ullswater, Derwent Water and Bassenthwaite Lake and swim the entire Bassenthwaite Lake length of Wast Water, Crummock Water and Buttermere. The lake's catchment is the largest of any lake in the Lake District. This, along with a large percentage of cultivable land It’s a once in a year event, so come and join this incredible within this drainage area, makes Bassenthwaite Lake a fertile journey. Swimmers will be escorted by experienced swim habitat. Cormorants have been known to fish the lake guides, qualified canoeists and safety craft. and herons can also be seen. Ullswater Who is it for? Ullswater is the second largest lake. On average it is 3/4 mile wide and has a maximum depth of 205 feet at Howtown, where The swimmer looking to swim across all the big lakes in a we finish our trip. It has three distinct bends giving it a dog’s leg safe and structured environment in the wonderful waters of appearance. the English Lake District. Trip Schedule Location Summaries Windermere Start Point: Brathay Hall, Ambleside LA22 0HP Windermere, at 10½ miles long, one mile wide and 220 feet www.brathay.org.uk/about-us/venue deep, is the largest natural lake in England, and is fed by +44 (0)15394 33041 numerous rivers. -

Hawkshead Sense of Place.Qxd:Millom Lflt

Getting around The Cross Lakes Experience allows you to explore the area without a car. Combining travel by lake steamers and launches, Mountain Goat minibus and Stagecoach buses allows car-free access a sense of place to Windermere, Bowness, Hawkshead, Grizedale and Coniston. Seasonal service. For timetable information, telephone 015394 45161 or visit www.mountain-goat.com By Bus Service 505 (Coniston Rambler) – Daily service between Windermere and Coniston, via Brockhole, Ambleside and Hawkshead. hawkshead This is a landscape of undulating farmland, mixed woodlands and Service 516 (Langdale Rambler) – Daily service between Ambleside and Great Langdale (Apr-Oct only). small tarns, interspersed with traditional Lakeland farmhouses and Service X30 (Grizedale Wanderer) – Haverthwaite to Hawkshead (via Newby Bridge, Lakeside and cottages. In the heart of this attractive area lies Hawkshead, a Grizedale). This special service is provided by the Forestry Commission to provide car-free access to Grizedale Forest Park, and links in with the X35 service between Kendal and Barrow. Daily service picturesque village of neat whitewashed cottages with roofs of grey from March to November. www.forestry.gov.uk/northwestengland local slate. Its name is derived from Hawkr’s Saeter (or Summer Service X31 (Tarn Hows Tourer) – Small 8-seater bus linking Tarn Hows with Ulverston, Newby Bridge, Pasture) – a Norse settlement founded in an area of summer grazing Coniston and Hawkshead, with a link to Grizedale Forest Park. Daily service with restricted timetable for sheep and cattle. on Saturdays and Sundays. Timetable can be downloaded from www.nationaltrust.org.uk (Coniston and Tarn Hows page). By the 12th century, Hawkshead and most of the surrounding land was a By Boat Jump on board one of the Windermere steamers or launches to visit Wray Castle, Brockhole or monastic grange run by the monks of Furness Abbey as a sheep ‘walk’.