Scriptures, Sacred Traditions, and Strategies of Religious Subversion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Garden of Eden to the New Creation in Christ : a Theological Investigation Into the Significance and Function of the Ol

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2017 From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old estamentT imagery of Eden within the New Testament James Cregan The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Cregan, J. (2017). From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old Testament imagery of Eden within the New Testament (Doctor of Philosophy (College of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/181 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM THE GARDEN OF EDEN TO THE NEW CREATION IN CHRIST: A THEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION INTO THE SIGNIFICANCE AND FUNCTION OF OLD TESTAMENT IMAGERY OF EDEN WITHIN THE NEW TESTAMENT. James M. Cregan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame, Australia. School of Philosophy and Theology, Fremantle. November 2017 “It is thus that the bridge of eternity does its spanning for us: from the starry heaven of the promise which arches over that moment of revelation whence sprang the river of our eternal life, into the limitless sands of the promise washed by the sea into which that river empties, the sea out of which will rise the Star of Redemption when once the earth froths over, like its flood tides, with the knowledge of the Lord. -

![Review: [Untitled] Reviewed Work(S): Savior Et Salut: Gnoses De L'antiquité Tardive by Gedaliahu Guy Stroumsa Paula Fredriksen](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1326/review-untitled-reviewed-work-s-savior-et-salut-gnoses-de-lantiquit%C3%A9-tardive-by-gedaliahu-guy-stroumsa-paula-fredriksen-821326.webp)

Review: [Untitled] Reviewed Work(S): Savior Et Salut: Gnoses De L'antiquité Tardive by Gedaliahu Guy Stroumsa Paula Fredriksen

Review: [Untitled] Reviewed Work(s): Savior et Salut: Gnoses de l'Antiquité Tardive by Gedaliahu Guy Stroumsa Paula Fredriksen The Jewish Quarterly Review, New Ser., Vol. 86, No. 1/2. (Jul. - Oct., 1995), pp. 195-197. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0021-6682%28199507%2F10%292%3A86%3A1%2F2%3C195%3ASESGDL%3E2.0.CO%3B2-F The Jewish Quarterly Review is currently published by University of Pennsylvania Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/upenn.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. -

Facts and Data

FACTS AND D ATA COLLÈGE DE FRANCE ORGANIZATION CHART Administrator of the Collège de France: Pierre CORVOL The Administrator of the Collège de France is a Collège de France professor, elected by his/her colleagues to direct the institution for a period of 3 years. Professors of the Collège de France I – MATHEMATICAL, PHYSICAL AND NATURAL SCIENCES ❍ Analysis and Geometry — Alain CONNES ❍ Differential Equations and Dynamical Systems — Jean-Christophe YOCCOZ ❍ Partial Differential Equations and Applications — Pierre-Louis LIONS ❍ Number Theory — Don ZAGIER ❍ Quantum Physics — Serge HAROCHE ❍ Mesoscopic Physics — Michel DEVORET ❍ Physics of Condensed Matter — Antoine GEORGES ❍ Elementary Particles, Gravitation and Cosmology — Gabriele VENEZIANO ❍ Climate and Ocean Evolution — Édouard BARD ❍ Observational Astrophysics — Antoine LABEYRIE ❍ Chemistry of biological processes — Marc FONTECAVE ❍ Chemistry of Molecular Interactions — Jean-Marie LEHN ❍ Human Genetics — Jean-Louis MANDEL ❍ Genetics and Cellular Physiology — Christine PETIT ❍ Biology and Genetics of Development — Spyros ARTAVANIS-TSAKONAS ❍ Morphogenetic Processes — Alain PROCHIANTZ ❍ Molecular Immunology — Philippe KOURILSKY ❍ Microbiology and infectious diseases — Philippe SANSONETTI ❍ Experimental Cognitive Psychology — Stanislas DEHAENE ❍ Physiology of Perception and Action — Alain BERTHOZ ❍ Experimental Medicine — Pierre CORVOL ❍ Historical Biology and Evolutionism — Armand de RICQLÈS ❍ Human Paleontology — Michel BRUNET II – HUMAN AND SOCIAL SCIENCES ❍ Pharaonic Civilization: -

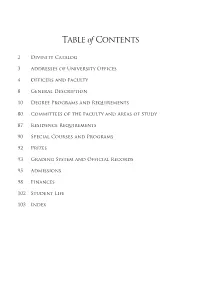

2018-2019 University of Chicago 3

Table of Contents 2 Divinity Catalog 3 Addresses of University Offices 4 Officers and Faculty 8 General Description 10 Degree Programs and Requirements 80 Committees of the Faculty and Areas of Study 87 Residence Requirements 90 Special Courses and Programs 92 Prizes 93 Grading System and Official Records 95 Admissions 98 Finances 102 Student Life 103 Index 2 Divinity Catalog Divinity Catalog Announcements 2018-2019 Welcome to the University of Chicago Divinity School. More information regarding the University of Chicago Divinity School can be found online at http:// divinity.uchicago.edu. Or you may contact us at: Divinity School University of Chicago 1025 E. 58th St. Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone: 773-702-8200 Photograph by Alex S. MacLean. The information in these Announcements is correct as of August 1, 2018. It is subject to change. 2018-2019 University of Chicago 3 Addresses of University Offices Requests for information, materials, and application forms for admission and financial aid should be addressed as follows: For all matters pertaining to the Divinity School: Dean of Students The University of Chicago Divinity School 1025 East 58th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 Phone: 773-702-8217 Fax: 773-834-4581 Web site: http://divinity.uchicago.edu For the Graduate Record Examination: Graduate Record Examination P.O. Box 6000 Princeton New Jersey 08541-6000 Phone: 609-771-7670 Web site: http://www.gre.org For FAFSA forms: Federal Student Aid Information Center P.O. Box 84 Washington, D.C. 20044 Phone: 800-433-3243 Web site: http://www.fafsa.gov For Housing: Residential Properties (RP) 773.753.2218 | [email protected] Web site: http://rp.uchicago.edu/ International House 1414 East 59th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 Phone: 773-753-2280 Fax: 773-753-1227 Web site: http://ihouse.uchicago.edu For Student Loans: Graduate Aid Walker Museum 1115 E. -

Martin Buber in Palestine/Israel on the Occasion of the 50 Anniversary of Martin Buber’S Death 50 Years of Israeli German Relations

Multiple Dialogues: Martin Buber in Palestine/Israel On the Occasion of the 50 Anniversary of Martin Buber’s Death 50 Years of Israeli German Relations International Conference Jerusalem, May 7-12, 2015 Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem; The Martin Buber Society of Fellows, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem; Martin Buber Chair in Jewish Thought and Philosophy, Goethe University Frankfurt am Main Workshop Program Jerusalem, May 8, 2015 Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem 33 Bustenai Street, Jerusalem | Tel. 00972 (2) 5633790 | [email protected] Schedule: 9:00-9:30 Introduction: Paul Mendes-Flohr and Christian Wiese 9:30-9:45 Coffee break 9:45-11:15 Session 1: four parallel workshops 2: The Question of Unity: Between East and West - Buber and India Hanoch Ben-Pazi and Shimon Lev 3: Kingship of God: YHWH as King Christoph Schmidt and Yemima Hadad 4: Judaism and Christianity Shalom Ratzabi and Orr Scharf 5: Images and Anthropology Guy Stroumsa and Dustin Atlas 11:15-11:45 Snack lunch 11:45-13:15 Session 2: four parallel workshops 1: The Crisis of Modernity Uri Ram and William Plevan 6: The Eclipse of God Christian Wiese and Enrico Lucca 7: The Mission of Abraham: “Walk before God” (Gen.17:1) Ron Margolin and Toshihiro Horikawa 8: Martin Buber’s Understanding of Nationality David Ohana and Kotaro Hiraoka 13:15-13:30 Coffee break 13:30-14:15 Conclusion: Paul Mendes-Flohr and Christian Wiese Morning Session: 9:45-11:15 Workshop 2: The Question of Unity: Between East and West - Buber and India Discussants: Hanoch Ben-Pazi, Bar Ilan University; Shimon Lev, Hebrew University Language: English or Hebrew Text 1: Buber's introduction: Ecstatic Confessions in: Ecstatic Confessions, Paul Mendes- Flohr (Edit), San Francisco, 1985 Language: Origin: German / Translation: English, Hebrew Text 2: "The Spirit of the East and Judaism" Lanugage: Origin: Hebrew / Translation: English, Hebrew Focus: Text 1: pp.1, 4-5 Text 2: Hebrew, pp. -

Alterity and the Ascents of Emanuel Swedenborg and the Baal Shem Tov

Open Theology 2018; 4: 414–421 Phenomenology of Religious Experience II: Perspectives in Theology Rebecca Esterson* What Do the Angels Say? Alterity and the Ascents of Emanuel Swedenborg and the Baal Shem Tov https://doi.org/10.1515/opth-2018-0032 Received June 10, 2018; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper examines the history of boundary crossing and boundary preservation between Jews and Christians in the eighteenth century via an unorthodox path. Two men, a Swedish Lutheran natural philosopher and a charismatic Polish Rabbi, give their accounts of ascents to the heavens, both in the 1740s. The lives of Emanuel Swedenborg and the Baal Shem Tov did not intersect, but their other- worldly experiences tell related stories of strife between Jews and Christians while betraying something of a shared horizon concerning the future of their religious communities, and concerning sacred texts and their interpretation. Using a phenomenological framework informed by Emmanuel Levinas, and with theories of experience articulated by Steven Katz and Martin Jay at hand, this paper understands these accounts as articulations of relationship: not just the relationship between the subject and God, scripture, or the heavens, but articulations of the fraught relationship with the religious other in the earthly, human realm. By placing Swedenborg and the Besht, as it were, face to face, this paper emphasizes the presence of the religious other in their experiences, even in their private encounters with the Divine, and even though the intersubjectivity these experiences expose is characterized by difference, difficulty, and asymmetry. Keywords: Emmanuel Levinas; Jewish-Christian relations; religious experience; Emanuel Swedenborg; Baal Shem Tov; phenomenology; scripture; Hasidism; eighteenth century; Kabbalah; alterity The eighteenth century was a time of contradictions and counter-movements in Jewish-Christian relations. -

Community, Ritual, Identity

Sacrifice in Modernity: Community, Ritual, Identity Joachim Duyndam, Anne-Marie Korte and Marcel Poorthuis Sacrifice, Opfer, Yajna – the various terms for sacrifice that can be found across different religious traditions show the many aspects that are perceived as constituting its core business, such as making holy, gift-giving, exchange, or the loss of something valuable. Since the mid 19th century, scholars studying written or performed sacrificial acts have tried to capture its essence with concepts such as bribery (Edward Burnett Tylor), a gift to the gods (Marcel Mauss), an act of consensual violence (René Girard), or a matter of cooking (Charles Malamoud). The act of offering sacrifices is undoubtedly one of the most universal religious phenomena. From time immemorial, offering a sac- rifice has been considered the proper way to approach the godhead. Whether the goods to be offered were products from the harvest, the firstlings of the flock, flowers, or flour, the believers expressed their gratitude, begged for divine favours or tried to appease the godhead or the community.1 The trans- formations – or re-embodiments – of sacrifice that have taken place in many religions have included prayer, almsgiving, fasting, continence, and even mar- tyrdom. These acts not only imply an effort to offer something of value, but often also a form of self-surrender, a surrender to the divine. However, these sacrificial religious practices, as such, seem to have lost most of their relevance and resonance in the context of modern western societies. Secularization and the decline of institutional religion have rendered them obsolete, dissolving the specific contexts and discourses that made these practices self-evident and meaningful. -

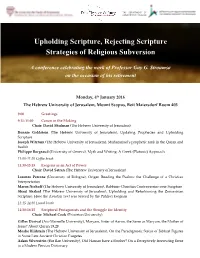

Upholding Scripture, Rejecting Scripture Strategies of Religious Subversion

THE DEPARTMENT OF THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE RELIGION COMPARATIVE RELIGION Upholding Scripture, Rejecting Scripture Upholding Scripture, Rejecting Scripture Strategies of Religious Subversion A conference celebrating the work of Professor Guy G. Stroumsa on the occasion of his retirement Monday, 4th January 2016 The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Mount Scopus, Beit Maiersdorf Room 405 9:00 Greetings 9:15-11:00 Canon in the Making Chair: David Shulman (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem) Ronnie Goldstein (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem), Updating Prophecies and Upholding Scripture Joseph Witztum (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem), Muhammad’s prophetic rank in the Quran and hadith Philippe Borgeaud (University of Geneva), Myth and Writing: A Greek (Platonic) Approach 11:00-11:30 Coffee break 11:30-13:15 Exegesis as an Act of Power Chair: David Satran (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem) Lorenzo Perrone (University of Bologna), Origen Reading the Psalms: the Challenge of a Christian Interpretation Maren Niehoff (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem), Rabbinic-Christian Controversies over Scripture Shaul Shaked (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem), Upholding and Refashioning the Zoroastrian Scripture: How the Avestan Text was Served by the Pahlavi Exegesis 13:15-14:30 Lunch break 14:30-16:15 Scriptural Protagonists and the Struggle for Identity Chair: Michael Cook (Princeton University) Gilles Dorival (Aix-Marseille University), Maryam, Sister of Aaron, the Same as Maryam, the Mother of Jesus? About Quran 19,28 Moshe Blidstein (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem), On the Paradigmatic Status of Biblical Figures in Some Late Ancient Christian Exegetes Adam Silverstein (Bar Ilan University), Did Haman have a Brother? On a Deceptively Interesting Error in a Modern Persian Dictionary 16:15 -16:45 Coffee break 16:45-18:00 Modern Reflections on Scripture and the History of Religions Chair: Sari Nusseibeh (Al-Quds University) Yonatan Moss (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem), Secret Mark Upheld, Secret Mark Rejected: Morton Smith, Gershom Scholem, and Guy G. -

1 Clothing Sacred Scriptures Materiality and Aesthetics in Medieval Book Religions

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2018 Clothing Sacred Scriptures. Materiality and Aesthetics in Medieval Book Religions Ganz, David DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110558609-001 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-161183 Book Section Published Version Originally published at: Ganz, David (2018). Clothing Sacred Scriptures. Materiality and Aesthetics in Medieval Book Religions. In: Ganz, David; Schellewald, Barbara. Clothing Sacred Scriptures, Book Arts and Book Religion in Christian, Islamic, and Jewish Cultures. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1-46. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110558609-001 David Ganz 1 Clothing Sacred Scriptures Materiality and Aesthetics in Medieval Book Religions In the early twelfth century, Turgot, the prior of the monas- one may judge Turgot’s miracle imputation, his account tery of Durham, composed the Life of Margaret, the shortly is related to a real and still existing Gospel book, now- deceased queen of Scotland. In an attempt to convince his adays kept in the Bodleian Library.3 Not long after Mar- readers of Margaret’s true sainthood, he not only provided garet’s death, another version of the same account was a long list of her pious deeds but concluded reporting a added to folio 2r of this manuscript.4 From this inscrip- miracle he judged most suitable for a person so devoted to tion in the book we learn that an individual book-object teaching and meditating on sacred scripture: with particular material properties is at the very center of this story. -

The Topic of Augustine and Manichaeism Has Been the Subject of Several Studies

1 AUGUSTINE’S MANICHAEAN DILEMMA IN CONTEXT Johannes van Oort Abstract This review article describes the study of ‘Augustine and Manichaeism’ in context, mainly focusing on the recent book on the theme (the first one of a projected trilogy) by Jason David BeDuhn. Keywords Augustine of Hippo; Mani; Manichaeism; Patristics; Roman Africa; Jason David BeDuhn Previous Research on Augustine and Manichaeism* The issue of ‘Augustine and Manichaeism’ has been dealt with in several studies. Most of these investigations are restricted to certain aspects of the subject, while only a very few consider the whole matter during all phases of Augustine’s life and in all of his works. In the German speaking world it was Ferdinand Christian Baur who, in a groundbreaking book on the Manichaean religion, paid attention to the immense quantity of material included in the writings of Augustine.1 Baur also made pertinent remarks on the church father’s relation to Manichaeism and the lasting influence Manichaeism may have exerted upon him.2 These remarks, however, were only asides made by the renowned scholar of the history of Christian dogma in a book the main interest of which was to provide an exposition of Mani’s ‘religious system’. In the French speaking world, the year 1918 saw the publication of the first (and only) volume of Prosper Alfaric’s L’évolution intellectuelle de saint Augustin.3 As stated in its subtitle, the impressive volume of no less than 556 pages focused on * The works of A. and Manichaean sources are abbreviated in accordance with common usage. Other abbreviations in the notes: A. -

Arbeitsberichte 195 the DISCRETE CHARM of INTELLECTUAL

THE DISCRETE CHARM OF INTELLECTUAL SUBVERSION GUY G. STROUMSA Guy G. Stroumsa is Martin Buber Professor Emeritus of Comparative Religion, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Professor Emeritus of the Study of the Abrahamic Reli- gions, and Emeritus Fellow of Lady Margaret Hall, University of Oxford. He is a Mem- ber of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities and holds an honorary doctorate from the University of Zurich. He is a laureate of the Humboldt Research Award and a Chevalier de l’Ordre du Mérite. Together with Sarah Stroumsa, he is the recipient of the Leopold- Lucas-Preis for 2018. Author of fourteen books and more than 130 articles; edi- tor or co-editor of 21 books. Recent publications: The Scriptural Universe of Ancient Chris- tianity (Cambridge, Mass., 2016); The Making of the Abrahamic Religions in Late Antiquity (Oxford, 2015); A New Science: the Discovery of Religion in the Age of Reason (Cambridge, Mass., 2010); and The End of Sacrifice: Religious Transformations of Late Antiquity ( Chicago, 2009; paperback 2012; original French edition, 2005; also Italian, German, and Hebrew translations). – Address: Department of Comparative Religion, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Mount Scopus, Jerusalem, 91905, Israel. E-mail: [email protected]. As a perusal of the many Jahrbücher kindly left on the shelves in the Fellows’ apartments will soon reveal, all superlatives, all possible metaphors about Wiko’s inimitability seem to have already been used. The deep gratitude for a magical period carved out of the fluid time of the rest of life is repeated, like a litany, in all reports. -

Dr. Adam Silverstein

Dr. Adam Silverstein Higher Education 1999-2002 Ph.D. in medieval Islamic Studies, Faculty of Oriental Studies and Trinity Hall, Cambridge University Dissertation: The Origins and Development of the Islamic Postal System Advisor: Prof. Tarif Khalidi 1995-1999 B.A. in Arabic and Persian (1st class), Faculty of Oriental Studies and Robinson College, Cambridge University Post Doctorate 2002-2005 Post Doctorate in Middle Eastern Studies, Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Cambridge. Research Project: The Origins and Development of the Islamic Postal System Career 2012-Present Associate Professor of Middle Eastern History, Department of Middle Eastern Studies, Bar Ilan University 2010-2012 Senior Lecturer, then Reader in Jewish Studies and Abrahamic Religions, Department of Theology and Religious Studies, King’s College London, University of London 2007-2010 Research Lecturer in Near Eastern Studies, The Oriental Institute, University of Oxford 2007-2010 Governing Body Fellow, The Queen’s College, Oxford. 2005-2007 Departmental Lecturer in Islamic History, The Oriental Institute, University of Oxford. Awards and Fellowships 2007-2010 Fellowship at the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies 2002-2005 British Academy Fellowship for Post-Doctorate at the University of Cambridge 2002-2003 Placed on final shortlist (interview) for Fellowship at All Souls College, Oxford; runner up (interview) for fellowship, Queens’ College, Cambridge; final shortlist for fellowship, Clare College, Cambridge, and St. John’s College, Cambridge; shortlist for fellowship, Clare Hall, Cambridge. 2002 R.A. Nicholson Prize for Ph.D., dissertation on The Origins and Development of the Islamic Postal System 2001 Awarded R. A. Nicholson Prize for outstanding Ph.D.