The Prince, the Punisher, and the Perpetrator

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF ^ the Three Feathers and Other Grimm Fairy Tales

E4EZ2UX9LS09 » Kindle » The Three Feathers and Other Grimm Fairy Tales (Paperback) Th e Th ree Feath ers and Oth er Grimm Fairy Tales (Paperback) Filesize: 6.06 MB Reviews Completely essential read pdf. It is definitely simplistic but shocks within the 50 % of your book. Its been designed in an exceptionally straightforward way which is simply following i finished reading through this publication in which actually changed me, change the way i believe. (Damon Friesen) DISCLAIMER | DMCA J7VNF6BTWRBI # Kindle < The Three Feathers and Other Grimm Fairy Tales (Paperback) THE THREE FEATHERS AND OTHER GRIMM FAIRY TALES (PAPERBACK) Caribe House Press, LLC, 2016. Paperback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****.In The Three Feathers and Other Grimm Fairy Tales, translator Catherine Riccio-Berry has remained faithful to the original German folk tales while also demonstrating her own keen ear for the language of playful storytelling. These eighteen carefully selected narratives are among the most engaging to be found in the Grimm Brothers extensive collection. In addition to four classic stories--Snow White, Little Red Riding Hood, Rumpelstiltskin, and Cinderella--this modernized and highly accessible translation also includes a delightful variety of lesser-known tales that range in tone from silly to moralizing to outright violent. Complete list of stories in this collection: The Three Feathers Fitcher s Pheasant Snow White The Story of Hen s Death Little Brother and Little Sister Little Red Riding Hood Hans my Hedgehog Straw, Coal, and Bean The Earth Gnome Doctor Know-It-All Bearskin Mrs. Trudy Mr. Korb Rumpelstiltskin Faithful John The Selfish Son Spindle, Shuttle, and Needle Cinderella. -

Fairy Tales and Folklore Countries

Recommended Reading Fairy Tales and Folklore Title Call Number AR North America The Jack Tales J 398.2 Cha - Tomie dePaola's front porch tales & North… J 398.2 DeP 4.8/1 The People Could Fly J 398.2 Ham 4.3/4 Waynetta and the cornstalk: a Texas fairy… J 398.2 Ket 3.3/0.5 The Frog Princess: a Tlingit Legend… [Alaska] J 398.2 Kim 3.5/0.5 Davy Crockett gets hitched J 398.2 Mil 4.2/0.5 Sister tricksters: rollicking tales of clever… J 398.2 San - Bubba the cowboy prince: a fractured Texas… E Ket 3.8/0.5 Nacho and Lolita [Mexico] E Rya 4.4/0.5 The Stinky Cheese Man and other fairly stupid tales E Sci 3.4/0.5 The princess and the warrior: a tale of two… [Mexico] E Ton 4.3/0.5 Native American The girl who helped thunder and other… J 398.08997 Bru 5.2/3 The Great Ball Game: a Muskogee story J 398.2 Bru 3.1/0.5 Yonder Mountain: a Cherokee legend J 398.2 Bus 3.8/0.5 The man who dreamed of elk-dogs: & other… J 398.2 Gob - The gift of the sacred dog J 398.2 Gob 4.2/0.5 Snow Maker’s Tipi E Gob - Central/ South America The great snake: stories from the Amazon J 398.2 Tay 4.4/1 The sea serpent's daughter: a Brazilian legend J 398.21 Lip 4.0/0.5 The little hummingbird J 398.24 Yah - The night the moon fell: a Maya myth J 398.25 Mor 3.4/ 0.5 Europe The twelve dancing princesses J 398.2 Bar 4.9/0.5 The king with horse's ears and other…[Ireland] J 398.2 Bur - Hans my hedgehog: a tale from…[Germany] J 398.2 Coo 4.6/0.5 Updated September 2017 Recommended Reading Fairy Tales and Folklore Title Call Number AR Europe (continued) Little Roja Riding Hood [Spain] -

David Mamet in Conversation

David Mamet in Conversation David Mamet in Conversation Leslie Kane, Editor Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2001 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ∞ Printed on acid-free paper 2004 2003 2002 2001 4 3 2 1 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data David Mamet in conversation / Leslie Kane, editor. p. cm. — (Theater—theory/text/performance) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-472-09764-4 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-472-06764-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Mamet, David—Interviews. 2. Dramatists, American—20th century—Interviews. 3. Playwriting. I. Kane, Leslie, 1945– II. Series. PS3563.A4345 Z657 2001 812'.54—dc21 [B] 2001027531 Contents Chronology ix Introduction 1 David Mamet: Remember That Name 9 Ross Wetzsteon Solace of a Playwright’s Ideals 16 Mark Zweigler Buffalo on Broadway 22 Henry Hewes, David Mamet, John Simon, and Joe Beruh A Man of Few Words Moves On to Sentences 27 Ernest Leogrande I Just Kept Writing 31 Steven Dzielak The Postman’s Words 39 Dan Yakir Something Out of Nothing 46 Matthew C. Roudané A Matter of Perception 54 Hank Nuwer Celebrating the Capacity for Self-Knowledge 60 Henry I. Schvey Comics -

The Tales of the Grimm Brothers in Colombia: Introduction, Dissemination, and Reception

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2012 The alest of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception Alexandra Michaelis-Vultorius Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Michaelis-Vultorius, Alexandra, "The alet s of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception" (2012). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 386. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE TALES OF THE GRIMM BROTHERS IN COLOMBIA: INTRODUCTION, DISSEMINATION, AND RECEPTION by ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: MODERN LANGUAGES (German Studies) Approved by: __________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my parents, Lucio and Clemencia, for your unconditional love and support, for instilling in me the joy of learning, and for believing in happy endings. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This journey with the Brothers Grimm was made possible through the valuable help, expertise, and kindness of a great number of people. First and foremost I want to thank my advisor and mentor, Professor Don Haase. You have been a wonderful teacher and a great inspiration for me over the past years. I am deeply grateful for your insight, guidance, dedication, and infinite patience throughout the writing of this dissertation. -

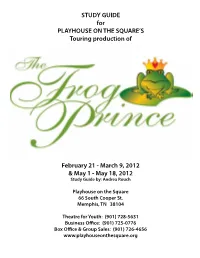

STUDY GUIDE for PLAYHOUSE on the SQUARE's

STUDY GUIDE for PLAYHOUSE ON THE SQUARE’S Touring production of February 21 - March 9, 2012 & May 1 - May 18, 2012 Study Guide by: Andrea Rouch Playhouse on the Square 66 South Cooper St. Memphis, TN 38104 Theatre for Youth: (901) 728-5631 Business Office: (901) 725-0776 Box Office & Group Sales: (901) 726-4656 www.playhouseonthesquare.org table of contents Part One: The Play.................................................................1 Synopsis................................................................................................................................................1 Vocabulary...................................................................................................................................................2 Part Two: Background...........................................................3 About the Playwright......................................................................................................................3 Origins of the Play..............................................................................................................................3 About Brothers Grimm....................................................................................................................4 Part Three: Activities and Discussion.................................5 Before Seeing the Play...................................................................................................................5 After Seeing the Play......................................................................................................................5 -

The Frog Prince

THE FROG PRINCE Adapted by MAX BUSH A play for young chil dren based on the Olenberg manu- script and var i ous edi tions of the tale The King’s Daugh ter and the En chanted Prince by the Brothers Grimm. Dra matic Pub lishing Woodstock, Il li nois • Eng land • Aus tra lia • New Zea land *** NO TICE *** The am a teur and stock act ing rights to this work are con trolled ex clu- sively by THE DRA MATIC PUB LISHING COM PANY with out whose per mis sion in writ ing no per for mance of it may be given. Roy alty must be paid ev ery time a play is per formed whether or not it is pre sented for profit and whether or not ad mis sion is charged. A play is per formed any time it is acted be fore an au di ence. Current roy alty rates, appli ca tions and re stric tions may be found at our website: www.dramaticpublishing.com, or we may be con tacted by mail at: DRA MATIC PUB LISHING COM- PANY, 311 Wash ing ton St., Woodstock IL 60098. COPY RIGHT LAW GIVES THE AU THOR OR THE AU THOR’S AGENT THE EX CLU SIVE RIGHT TO MAKE COPIES. This law pro - vides au thors with a fair re turn for their cre ative ef forts. Au thors earn their liv ing from the royal ties they receive from book sales and from the per for mance of their work. Con sci en tious ob ser vance of copy right law is not only eth i cal, it en cour ages au thors to con tinue their cre ative work. -

Fairy Tales in European Context Gen Ed Course Submission: for Inquiry – Humanitites

GER 103: Fairy Tales in European Context Gen Ed Course Submission: for Inquiry – Humanitites 2 lectures PLUS 1 discussion section: Professor Linda Kraus Worley 1063 Patterson Office Tower Phone: 257 1198 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Wednesdays 10 - 12; Fridays 10 – 12 and by appointment FOLKTALES AND FAIRY TALES entertain and teach their audiences about culture. They designate taboos, write out life scripts for ideal behaviors, and demonstrate the punishments for violating the collective and its prescribed social roles. Tales pass on key cultural and social histories all in a metaphoric language. In this course, we will examine a variety of classical and contemporary fairy and folktale texts from German and other European cultures, learn about approaches to folklore materials and fairy tale texts, and look at our own culture with a critical-historical perspective. We will highlight key issues, values, and anxieties of European (and U.S.) culture as they evolve from 1400 to the present. These aspects of human life include arranged marriage, infanticide, incest, economic struggles, boundaries between the animal and human, gender roles, and class antagonisms. Among the tales we will read and learn to analyze using various interpretive methods are tales collected by the Brothers Grimm, by the Italians Basile and Straparola, by seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French writers such as D‘Aulnoy, de Beaumont, and Perrault, by Hans Christian Andersen and Oscar Wilde. We will also read 20th century re-workings of classical fairy tale motifs. The course is organized around clusters of Aarne, Thompson and Uther‘s ―tale types‖ such as the Cinderella, Bluebeard, and the Hansel-and-Gretel tales. -

"Fathers and Daughters"

"Fathers and Daughters" Critic: James M. McGlathery Source: Fairy Tale Romance: The Grimms, Basile, and Perrault, pp. 87-112. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991. [(essay date 1991) In the following essay, McGlathery explores the erotic implications of the father-daughter relationship in the romantic folktales of the Brothers Grimm, Giambattista Basile, and Charles Perrault, highlighting common plot scenarios.] As the stories discussed thus far show, emotional involvement between parents and children is a frequent object of portrayal in folktales. That this is especially true of the romantic tale should come as no surprise, for in love plots generally the requisite hindrance to the fulfillment of young desire often takes the form of parental objection or intervention. There are surprises to be found here, however. In particular, the romantic folktale offers the possibility of hinting, with seeming innocence, at erotically tinged undercurrents in the relationship between parent and child that do not lend themselves to tasteful direct portrayal. Fairy tale romance often depicts the child's first experience of leaving home and venturing out on its own, usually in connection with choosing a mate. In the stories of the brother and sister type, resistance to the taking of this step is reflected in a desire to return to the bosom of the family or, failing that, to retain the devoted company of one's siblings. Thus, we have seen how Hansel and Gretel, while prepared to survive together in the forest if need be are overjoyed at being able to live with their father, and how the sister in "The Seven Ravens" succeeds in restoring her brothers to human form and bringing them home with her. -

1457878351568.Pdf

— Credits — Authors: Patrick Sweeney, Sandy Antunes, Christina Stiles, Colin Chapman, and Robin D. Laws Additional Material: Keith Sears, Nancy Berman, and Spike Y Jones Editor: Spike Y Jones Index: Janice M. Sellers Layout and Graphic Design: Hal Mangold Cover Art: Patricia Ann Lewis-MacDougall Interior Art: Janet Chui, Patricia Ann Lewis-MacDougall and Jennifer Meyer Playtesters: Elizabeth, Joey, Kathryn, Lauren, Ivy, Kate, Miranda, Mary, Michele, Jennifer, Rob, Bethany, Jacob, John, Kelly, Mark, Janice, Anne, and Doc Special Thanks To: Mark Arsenault, Elissa Carey, Robert “Doc” Cross, Darin “Woody” Eblom, Larry D. Hols, Robin D. Laws, Nicole Lindroos, David Millians, Rob Miller, Liam Routt, and Chad Underkoffler If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales. —Albert Einstein Copyright 2007 by Firefly Games. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention. Faery’s Tale and all characters and their likenesses are trademarks owned by and/or copyrights by Firefly Games. All situations, incidents and persons portrayed within are fictional and any similarity without satiric intent to individuals living or dead is strictly coincidental. Designed and developed by Firefly Games, 4514 Marconi Ave. #3, Sacramento CA 95821 [email protected] Visit our website at www.firefly-games.com. Published by Green Ronin Publishing 3815 S. Othello St. Suite 100, #304, Seattle, WA 98118 [email protected] Visit our website at www.greenronin.com. Table of Contents Preface .........................................................................3 A Sprite’s Tale .......................................................49 A Pixie’s Tale .............................................................4 Faery Princesses & Magic Wands ............51 Introduction ................................................................7 Titles .................................................... -

Fairy Tales Retold for Older Readers

Story Links: Fairy Tales retold for Older Readers Fairy Tales Retold for Older Readers in Years 10, 11 and 12 These are just a few selections from a wide range of authors. If you are interested in looking at more titles these websites The Best Fairytale Retellings in YA literature, GoodReads YA Fairy Tale Retellings will give you more titles. Some of these titles are also in the companion list Fairy Tales Retold for Younger Readers. Grimm Tales for Young and Old by Philip Pullman In this selection of fairy tales, Philip Pullman presents his fifty favourite stories from the Brothers Grimm in a clear as water retelling, making them feel fresh and unfamiliar with his dark, distinctive voice. From the otherworldly romance of classics such Rapunzel, Snow White, and Cinderella to the black wit and strangeness of such lesser-known tales as The Three Snake Leaves, Hans-my-Hedgehog, and Godfather Death. Tinder by Sally Gardiner, illustrated by David Roberts Otto Hundebiss is tired of war, but when he defies Death he walks a dangerous path. A half beast half man gives him shoes and dice which will lead him deep into a web of dark magic and mystery. He meets the beautiful Safire, the scheming Mistress Jabber and the terrifying Lady of the Nail. He learns the powers of the tinderbox and the wolves whose master he becomes. But will all the riches in the world bring him the thing he most desires? This powerful and beautifully illustrated novel is inspired by the Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale, The Tinderbox. -

Once Upon a Time

The Snow Queen The three billy goats gruff by Natacha Godeau by Jerry Pinkney Once Upon a Time When her friend Hans is Three billy goats must outwit the kidnapped by the mysterious big, ugly troll that lives under the Favorite Fairy Tale Picture Books Snow Queen, Hanna decides to bridge they have to cross on look for him wherever her their way up the mountain. Beauty and the Beast search might take her. by Cynthia Rylant Puss in Boots Through her great capacity to Cinderella by Paul Galdone love, a kind and beautiful maid by Sarah L. Thomson A poor young man gains a releases a handsome prince Although mistreated by her fortune and meets a beautiful from the spell which has made him an ugly beast. stepmother and stepsisters, princess when his cat, the clever Cinderella meets her prince with Puss, outwits an evil giant. Rimonah of the Flashing Sword the help of her fairy godmother. by Eric A. Kimmel Hansel & Gretel A North African version of Snow Hans My Hedgehog by Holly Hobbie White tells of the beautiful by Kate Coombs Hansel and Gretel become lost Rimonah, whose courage and Riding a rooster and playing his in the woods and must find their honesty win her many rewards. fiddle, a young man, who is half way home despite an encounter hedgehog, half human, wins the with a wicked witch. The elves and the shoemaker hand of a beautiful princess. by Mara Alperin A catfish tale A poor shoemaker becomes Firebird by Whitney Stewart successful with the help of two by Saviour Pirotta When Cajun fisherman Jacques elves who finish his shoes during When a Firebird is discovered encounters a wish-granting the night. -

Schutz Theatre FT June 2021

THE W. STANLEY SCHUTZ THEATRE COLLECTION: THE COLLEGE OF WOOSTER PRODUCTIONS FINDING TOOL Denise Monbarren June 2021 FINDING TOOL SCHUTZ COLLECTION Box 1 #56 Productions: 1999 X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets AARON SLICK FROM PUNKIN CRICK Productions: 1960 X-Refs. Clippings [about] Flyers, Pamphlets Photographs Playbills Postcards ABIE’S IRISH ROSE Productions: 1945, 1958 X-Refs. Clippings [about] Photographs [of] Playbills Postcards ABOUT WOMEN Productions: 1997 Flyers, Pamphlets Invitations ACT OF MADNESS Productions: 2003 Flyers, Pamphlets THE ACTING RECITALS Productions: 2003, 2004 Flyers, Pamphlets Playbills ADAIR, TOM X-Refs. ADAM AND EVA Productions: 1922 X-Refs. Playbills AESOP’S FALABLES Productions: 1974 X-Refs. Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets Itineraries Notes Photographs [of] Playbills AFRICAN-AMERICAN PERFORMING ARTS FESTIVAL Productions: [n.d.] Playbills AGAMEMNON Productions: 2003 X-Refs. THE AGES OF WOMAN Productions: 1964 Playbills AH, WILDERNESS Productions: 1966, 1987 X-Refs. Photographs [of] Playbills ALABAMA Productions: 1918 X-Refs. Playbills Box 2 ALCESTIS Productions: [1955] X-Refs. Playbills ALICE IN WONDERLAND Productions: 1955, 1974 X-Refs. Artwork [about] Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets Invitations Itineraries Notes ALL IN THE TIMING Productions: 2002 X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location Press Releases ALL MY SONS Productions: 1968, 2006 X-Refs. Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location Invitations Photographs [of] Playbills Postcards Press Releases ALL THE COMFORTS OF HOME Productions: 1912 X-Refs. Playbills ALLARDICE, JAMES See PEACOCK IN THE PARLOR ALMOST, MAINE Productions: 2017 X-Refs. Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location Press Releases Box 3 AMADEUS Productions: [1985] X-Refs. Playbills AMAHL AND THE NIGHT VISITORS Productions: 1969 See also: HELP, HELP, THE GLOBOLINKS! X-Refs.