Crossing the Black Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Camps, As Camps Will Be Cancelled for Low Enrollment

BENICIA PARKS & COMMUNITY SERVICES DEPARTMENT CONTACTS Mike Dotson, Director Ann Dunleavy, Superintendent OFFICE LOCATION: Benicia Community Center Theron Jones, Superintendent 370 East L Street Victor Randall, Management Analyst Benicia, CA 94510 Lindsay Zarcone, Recreation Supervisor Phone: (707) 746-4285 Wendy Stratton Monahan, Recreation Supervisor www.beniciarec.org Eliot Palmer, Recreation Supervisor [email protected] Debbi Bray, Administrative Clerk Rachel Morgado, Recreation Specialist OFFICE HOURS: Monday–Friday, 8am – 5pm For direct contact information, visit www.beniciarec.org You can register for our classes and programs at our office, or online at www.beniciarec. org. Payments at the office can be made with cash, check, VISA, Mastercard, or American Express. Online registrations requires a login and password. Please stop by or call our office to set up an account to access online registration. Full credit will be given to cancellations received 72 hours prior to the first class, unless otherwise noted in the program description. Failure to attend a class session will not be granted a credit/refund. Trip refunds will only be considered with prior notice of 15 days or more before trip departure. Exceptions are at the discretion of the program supervisor. Time, dates, and locations of classes are subject to change. Please contact the Recreation Supervisor if you are not satisfied with a program. We offer a satisfaction guaranteed policy. Credits/refunds will be offered if requested prior to the second class session, if you are not satisfied with the program. This guarantee does not apply to youth and adult sports leagues, trips, facility rentals, recreation swim, and single day events, classes, or activities. -

APPENDIX a – Initial List of Stations Eligible for Analog Nightlight Program

Federal Communications Commission FCC 08-281 APPENDIX A – Initial List of Stations Eligible for Analog Nightlight Program Market Facility ID Call sign City ST Analog Digital Anlg Ch. Post Pre Status of Analog Transition Transition DTV Ch. DTV Ch. (*) Anchorage, AK 804 KAKM Anchorage AK PBS PBS 7 8 Anchorage, AK 13815 KIMO Anchorage AK ABC ABC 13 12 Anchorage, AK 10173 KTUU-TV Anchorage AK NBC NBC 2 10 Anchorage, AK 4983 KYUK-TV Bethel AK 4 3 Fairbanks, AK 13813 KATN Fairbanks AK ABC ABC 2 18 Fairbanks, AK 20015 KJNP-TV North Pole AK 4 20 Fairbanks, AK 49621 KTVF Fairbanks AK NBC NBC 11 26 Fairbanks, AK 69315 KUAC-TV Fairbanks AK 9 9 24 Juneau, AK 8651 KTOO-TV Juneau AK PBS PBS 3 10 Juneau, AK 60520 KUBD Ketchikan AK CBS CBS 4 13 Birmingham, AL 71325 WDBB Bessemer AL 17 18 Dothan, AL 43846 WDHN Dothan AL ABC ABC 18 21 Huntsville-Decatur-Florence, AL 57292 WAAY-TV Huntsville AL ABC ABC 31 32 Montgomery, AL 714 WDIQ Dozier AL PBS PBS 2 10 Ft. Smith-Fayetteville-Springdale-Rogers, AR 66469 KFSM-TV Fort Smith AR CBS CBS 5 18 Ft. Smith-Fayetteville-Springdale-Rogers, AR 60354 KHOG-TV Fayetteville AR ABC ABC 29 15 Little Rock-Pine Bluff, AR 33440 KARK-TV Little Rock AR NBC NBC 4 32 Little Rock-Pine Bluff, AR 2770 KETS Little Rock AR PBS PBS 2 7 Terminating 1/3/09 Little Rock-Pine Bluff, AR 11951 KLRT-TV Little Rock AR Fox Fox 16 30 Little Rock-Pine Bluff, AR 37005 KWBF Little Rock AR 42 44 Reduced 10/31/08 Phoenix, AZ 41223 KPHO-TV Phoenix AZ CBS CBS 5 17 Phoenix, AZ 40993 KTVK Phoenix AZ 3 24 Phoenix, AZ 68886 KUTP Phoenix AZ 45 26 Tucson, -

Hooray for Health Arthur Curriculum

Reviewed by the American Academy of Pediatrics HHoooorraayy ffoorr HHeeaalltthh!! Open Wide! Head Lice Advice Eat Well. Stay Fit. Dealing with Feelings All About Asthma A Health Curriculum for Children IS PR O V IDE D B Y FUN D ING F O R ARTHUR Dear Educator: Libby’s® Juicy Juice® has been a proud sponsor of the award-winning PBS series ARTHUR® since its debut in 1996. Like ARTHUR, Libby’s Juicy Juice, premium 100% juice, is wholesome and loved by kids. Promoting good health has always been a priority for us and Juicy Juice can be a healthy part of any child’s balanced diet. Because we share the same commitment to helping children develop and maintain healthy lives, we applaud the efforts of PBS in producing quality educational television. Libby’s Juicy Juice hopes this health curriculum will be a valuable resource for teaching children how to eat well and stay healthy. Enjoy! Libby’s Juicy Juice ARTHUR Health Curriculum Contents Eat Well. Stay Fit.. 2 Open Wide! . 7 Dealing with Feelings . 12 Head Lice Advice . 17 All About Asthma . 22 Classroom Reproducibles. 30 Taping ARTHUR™ Shows . 32 ARTHUR Home Videos. 32 ARTHUR on the Web . 32 About This Guide Hooray for Health! is a health curriculum activity guide designed for teachers, after-school providers, and school nurses. It was developed by a team of health experts and early childhood educators. ARTHUR characters introduce five units exploring five distinct early childhood health themes: good nutrition and exercise (Eat Well. Stay Fit.), dental health (Open Wide!), emotions (Dealing with Feelings), head lice (Head Lice Advice), and asthma (All About Asthma). -

Kids with Asthma Can! an ACTIVITY BOOKLET for PARENTS and KIDS

Kids with Asthma Can! AN ACTIVITY BOOKLET FOR PARENTS AND KIDS Kids with asthma can be healthy and active, just like me! Look inside for a story, activity, and tips. Funding for this booklet provided by MUSEUMS, LIBRARIES AND PUBLIC BROADCASTERS JOINING FORCES, CREATING VALUE A Corporation for Public Broadcasting and Institute of Museum and Library Services leadership initiative PRESENTED BY Dear Parents and Friends, These days, almost everybody knows a child who has asthma. On the PBS television show ARTHUR, even Arthur knows someone with asthma. It’s his best friend Buster! We are committed to helping Boston families get the asthma care they need. More and more children in Boston these days have asthma. For many reasons, children in cities are at extra risk of asthma problems. The good news is that it can be kept under control. And when that happens, children with asthma can do all the things they like to do. It just takes good asthma management. This means being under a doctor’s care and taking daily medicine to prevent asthma Watch symptoms from starting. Children with asthma can also take ARTHUR ® quick relief medicine when asthma symptoms begin. on PBS KIDS Staying active to build strong lungs is a part of good asthma GO! management. Avoiding dust, tobacco smoke, car fumes, and other things that can start an asthma attack is important too. We hope this booklet can help the children you love stay active with asthma. Sincerely, 2 Buster’s Breathless Adapted from the A RTHUR PBS Series A Read-Aloud uster and Arthur are in the tree house, reading some Story for B dusty old joke books they found in Arthur’s basement. -

Fabled King Arthur 'Was Buried on Iona'

10 News Talk to us w scotlandonsunday.com myscotlandonsunday @scotonsunday November 17,2013 Fabled King Arthur ‘was buried on Iona’ Historian’sbooksayslegendary courtofCamelot wasinArgyll Emma Cowing says thattheycan be proved “beyond reasonable doubt”. WELCOME to MacCamelot. Theassertions in his book King Arthur was aScottish, Finding Arthur: The True pre-Christian warlord whose Origins Of The Once And remains are buried on Iona, FutureKing are strengthened according to anew book by a by the discoveryin2011of Scots historian. whatsome experts believe is Author Adam Ardreyclaims King Arthur’s round table in thatinstead of the romantic the grounds of Stirling Castle. English king of legend who Ardreysayshenot only be- lived at Camelot –which is lieves Arthur is buried in Iona often said to be Tintagel in but would love to see the site Cornwall or in Wales –Arthur excavated to look for proof. was actually Arthur Mac “The legendaryArthur is » Arthur is said to have pulled Excalibur from astone at Dunadd and, right, Aedan, the sixth-centuryson said to be buried in an island Iona Abbeyonthe isle whereitisclaimed he wasburied. Photograph: Alamy of an ancient King of Scotland, in the western seas –Avalon – whose Camelot was amarsh in but in the south of Britain of connectionsbetween Argyll land, including Stow in the cally,aswell as historically Thelegend of Arthur devel- It was hoped thatthe discov- Thebook also asserts that Argyll. there are no islands in the and Arthur are so numerous Borders, where he says the place them in context. Six of oped in the Middle Ages large- erycould prove thatKing Arthur became the victim of He also suggeststhatArthur western seas,”hesays. -

Checchi, Arthur A

HISTORY OF THE U. S. FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION Interview between: Arthur A. Checchi Fomer Assistant to Deputy Commissioner and Fred L. Lofsvold U. S. Food and Drug Administration Washington, D. C. July 24. 1984 This is a transcription of a taped interview, one of a series conducted by Robert G. Porter, Fred L. Lofsvold, and Ronald T. Ottes, retired employees of the U. S. Food and Drug Administration. The interviews are being held with F.D.A.. employees. both active and retired, whose recollections may serve to enrich the written record. It is hoped that these narratives of things past will serve as source material for present and future researchers; that the stories of important accomplishments, interesting events, and distinguished leaders will find a place in training and orientation of new employees, and may be useful to enhance the morale of the organization; and finallyithat they will be of value to Dr. James Harvey Young in the writing of the history of the Food and Drug Administration.. The tapes and transcriptions will become a part of the collection of the National Library of Medicine, and copies of the trans- criptions will be placed in the Library of Emory University. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES ruovc meawn aerviw Food and Drug Administration Room500 US. Customhouse 721 lgth Street Denver. Colorado 80202 303-837-4915 ---TAPE INDEX SHEET CASSETTE NUMBER(S) 1. 2 GENERAL TOPIC OF INTERVIEW: History of the Food and Druq Administration DATE: ~uly24, 1984 PLACE: Washington, D. C. LENGTH: 114 Min. INTERVIEWEE INTERVIEWER NAME: Arthur A. Checchi NAME: Fred L. -

THE TICK (A Parody) by Ben Edlund the TICK a Parody

THE TICK (A Parody) by Ben Edlund THE TICK A Parody FADE IN: EXT. EARTH - DAY The screen is filled with a perfect TICK BLUE. The whistling growl of A LOW TUVAN SINGER HUM intones. WIDEN SLOWLY TO REVEAL it’s the blue of an ocean from orbit. TICK (V.O.) Hey! HUMANITY! WIDENER - EARTH hangs in space. Just visible past it, the SUN scatters glancing rays in a dazzle of beauty. MORE VOICES join the deep HUM, build to a ‘Zarathustra’ chorus. TICK (V.O.) Long has been your adventure! Blood and broad-swords and dynasty and ziggurats and SO MUCH shipping! Man, you cats love movin’ stuff around... (deep seriousness) And always, underneath it all, the Eternal Struggle. A BLACK SHAPE tumbles over us: A MASSIVE ASTEROID falling towards our world. TICK (V.O.) The story of Light against Darkness. Of Good against Evil. The Battle for the fate of the world... The Hero’s Journey! Earth’s bottom arc fills upper frame. The tiny ASTEROID rises up vertically to it, trailing a WHITE HOT TAIL OF MOLTEN STRATOSPHERE [echo of sperm and ovum? YES!]. TICK (V.O.) This then, is that story. The most important story ever told... The blazing asteroid falls at us, FILLING FRAME with FIRE. A title SUPERS over the ROILING INCANDESCENCE: “THE TICK” TICK (V.O.) My story. 2/3/16 TICK 'Pilot' 2 EXT. TUNGUSKA RIVER BASIN - DAY Gorgeous vista. Trackless arctic forest. Dawn. The ASTEROID descends from the dome of sky. The end is near. ON REINDEER HERD - which chuffs and steams, clearing frame to reveal a TWO EVENKI TRIBESMEN; fur-clad, indigenous Siberians. -

Arthur WN Guide Pdfs.8/25

Building Global and Cultural Awareness Keep checking the ARTHUR Web site for new games with the Dear Educator: World Neighborhood ® ® has been a proud sponsor of the Libby’s Juicy Juice ® theme. RTHUR since its debut in award-winning PBS series A ium 100% 1996. Like Arthur, Libby’s Juicy Juice, prem juice, is wholesome and loved by kids. itment to a RTHUR’s comm Libby’s Juicy Juice shares A world in which all children and cultures are appreciated. We applaud the efforts of PBS in producingArthur’s quality W orld educational television and hope that Neighborhood will be a valuable resource for teaching children to understand and reach out to one another. Enjoy! Libby’s Juicy Juice Contents About This Guide. 1 Around the Block . 2 Examine diversity within your community Around the World. 6 Everyday Life in Many Cultures: An overview of world diversity Delve Deeper: Explore a specific culture Dear Pen Pal . 10 Build personal connections through a pen pal exchange More Curriculum Connections . 14 Infuse your curriculum with global and cultural awareness Reflections . 15 Reflect on and share what you have learned Resources . 16 All characters and underlying materials (including artwork) copyright by Marc Brown.Arthur, D.W., and the other Marc Brown characters are trademarks of Marc Brown. About This Guide As children reach the early elementary years, their “neighborhood” expands beyond family and friends, and they become aware of a larger, more diverse “We live in a world in world. How are they similar and different from others? What do those which we need to share differences mean? Developmentally, this is an ideal time for teachers and providers to join children in exploring these questions. -

Arthur's Computer Disaster

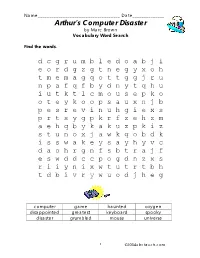

Name____________________________________ Date______________ Arthur’s Computer Disaster by Marc Brown Vocabulary Word Search Find the words. d c g r u m b l e d o a b j i e o r d g z g t n e g y x o h t m e m a g q o t t g g j r u n p a f q f b y d n y t q h u i u t k t l c m o u s e p k o o t e y k o o p s a u x n j b p e s r e v i n u h g i e x s p r t s y g p k r f z e h z m a e h q b y k a k u z p k i z s t u n o x j a w k q o b d k i s s w a k e y s a y h y v c d a o h r g n f s b t r a j f e s w d d c c p o g d n z x s r i i y n i x w t u t r t b h t d b i v r y w u o d j h e g computer game haunted oxygen disappointed greatest keyboard spooky disaster grumbled mouse universe 1 ©2004abcteach.com Name____________________________________ Date______________ Arthur’s Computer Disaster by Marc Brown Crossword Puzzle Complete the puzzle. -

United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County Hosts

For Immediate Release For more information, contact Rebecca Schimke, Communications Specialist [email protected] 414.263.8125 (O), 414.704.8879 (C) United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County Hosts Children’s Writer & Illustrator of Arthur Adventure Series, Marc Brown, to Promote Childhood Literacy Reading Blitz Day also celebrated Reader, Tutor, Mentor Volunteers. MILWAUKEE [March 25, 2015] – United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County hosted a Reading Blitz Day to celebrate a 3-year effort of recruiting and placing 4,800+ reader, tutor, and mentor volunteers throughout Greater Milwaukee. The importance of reading to kids cannot be overstated. “Once children start school, difficulty with reading contributes to school failure, which can increase the risk of absenteeism, leaving school, juvenile delinquency, substance abuse, and teenage pregnancy - all of which can perpetuate the cycles of poverty and dependency.” according to the non-profit organization, Reach Out & Read. “United Way recognizes that caring adults working with children of all ages has the power to boost academic achievement and set them on the track for success,” said Karissa Gretebeck, marketing and community engagement specialist, United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County. “We are thankful for the agency partners, other non-profits and schools who partnered with us to make this possible.” United Way also organized a book drive leading up to the day. New or gently used books were collected at 13 Milwaukee Public Library locations, Brookfield Public Library, Muskego Public Library and Martha Merrell’s Books in downtown Waukesha. Books from the drive will be donated to United Way funded partner agencies that were a part of the Reader, Tutor, Mentor effort. -

A Rational Solution to Cootie Arthur T

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont All HMC Faculty Publications and Research HMC Faculty Scholarship 3-1-2000 A Rational Solution to Cootie Arthur T. Benjamin Harvey Mudd College Matthew .T Fluet '99 Recommended Citation Benjamin, Arthur T. and Matthew T. Fluet. "A Rational Solution to Cootie." The oC llege Mathematics Journal, Vol 31, No. 2, pp. 124-125, March, 2000. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the HMC Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in All HMC Faculty Publications and Research by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Rational Solution to Cootie Author(s): Arthur T. Benjamin and Matthew T. Fluet Source: The College Mathematics Journal, Vol. 31, No. 2 (Mar., 2000), pp. 124-125 Published by: Mathematical Association of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2687584 . Accessed: 11/06/2013 19:21 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Mathematical Association of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The College Mathematics Journal. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 134.173.219.117 on Tue, 11 Jun 2013 19:21:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions CLASSROOM CAPSULES EDITOR Thomas A. -

Arthur's TV Trouble Work Page and Key FREE

Arthur's TV Trouble Name ___________________ Date __________ Read the book and answer the questions. When did Arthur begin to want to buy an amazing Treat Timer? ________________________________________________________ Why did Arthur want to buy it? ________________________________________________________________ Do you think Pal really needed a Treat Timer? Why or why not? ________________________________________________________________ How much money did Arthur have, even with all his birthday money? ________________________________________________________________ How much more money did he need to buy a Treat Timer? ________________________________________________________________ Why did Arthur have to retake the spelling test? ________________________________________________________________ What job did he do to earn money to buy the Treat Timer? ________________________________________________________________ Why do you think D.W. said Arthur was nicer when he was rich? ________________________________________________________________ How long did it take Arthur to assemble the Treat Timer? ________________________________________________________________ Did Arthur learn a lesson? Why or why not? ________________________________________________________________ Arthur's TV Trouble -- Teacher Answer Key 1. When did Arthur begin to want to buy an amazing Treat Timer? He thought it would be cool for his dog, Pal. 2. Why did Arthur want to buy it? He was fooled by the commercial (or just he saw a commercial) 3. Do you think Pal really needed a Treat Timer? Why or why not? Answers may vary, and any opinion is OK supported by a reason 4. How much money did Arthur have, even with all his birthday money? Ten dollars and three cents, or $10.03 5. How much more money did he need to buy a Treat Timer? $9.92 6. Why did Arthur have to retake the spelling test? He was daydreaming about the Treat Timer and didn't listen.