Download PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau

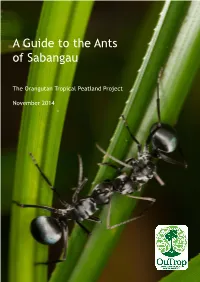

A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project November 2014 A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau All original text, layout and illustrations are by Stijn Schreven (e-mail: [email protected]), supple- mented by quotations (with permission) from taxonomic revisions or monographs by Donat Agosti, Barry Bolton, Wolfgang Dorow, Katsuyuki Eguchi, Shingo Hosoishi, John LaPolla, Bernhard Seifert and Philip Ward. The guide was edited by Mark Harrison and Nicholas Marchant. All microscopic photography is from Antbase.net and AntWeb.org, with additional images from Andrew Walmsley Photography, Erik Frank, Stijn Schreven and Thea Powell. The project was devised by Mark Harrison and Eric Perlett, developed by Eric Perlett, and coordinated in the field by Nicholas Marchant. Sample identification, taxonomic research and fieldwork was by Stijn Schreven, Eric Perlett, Benjamin Jarrett, Fransiskus Agus Harsanto, Ari Purwanto and Abdul Azis. Front cover photo: Workers of Polyrhachis (Myrma) sp., photographer: Erik Frank/ OuTrop. Back cover photo: Sabangau forest, photographer: Stijn Schreven/ OuTrop. © 2014, The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project. All rights reserved. Email [email protected] Website www.outrop.com Citation: Schreven SJJ, Perlett E, Jarrett BJM, Harsanto FA, Purwanto A, Azis A, Marchant NC, Harrison ME (2014). A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau. The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project, Palangka Raya, Indonesia. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of OuTrop’s partners or sponsors. The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project is registered in the UK as a non-profit organisation (Company No. 06761511) and is supported by the Orangutan Tropical Peatland Trust (UK Registered Charity No. -

Worldwide Spread of the Difficult White-Footed Ant, Technomyrmex Difficilis (Hymeno- Ptera: Formicidae)

Myrmecological News 18 93-97 Vienna, March 2013 Worldwide spread of the difficult white-footed ant, Technomyrmex difficilis (Hymeno- ptera: Formicidae) James K. WETTERER Abstract Technomyrmex difficilis FOREL, 1892 is apparently native to Madagascar, but began spreading through Southeast Asia and Oceania more than 60 years ago. In 1986, T. difficilis was first found in the New World, but until 2007 it was mis- identified as Technomyrmex albipes (SMITH, 1861). Here, I examine the worldwide spread of T. difficilis. I compiled Technomyrmex difficilis specimen records from > 200 sites, documenting the earliest known T. difficilis records for 33 geographic areas (countries, island groups, major islands, and US states), including several for which I found no previously published records: the Bahamas, Honduras, Jamaica, the Mascarene Islands, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Africa, and Washington DC. Almost all outdoor records of Technomyrmex difficilis are from tropical areas, extending into the subtropics only in Madagascar, South Africa, the southeastern US, and the Bahamas. In addition, there are several indoor records of T. dif- ficilis from greenhouses at zoos and botanical gardens in temperate parts of the US. Over the past few years, T. difficilis has become a dominant arboreal ant at numerous sites in Florida and the West Indies. Unfortunately, T. difficilis ap- pears to be able to invade intact forest habitats, where it can more readily impact native species. It is likely that in the coming years, T. difficilis will become increasingly more important as a pest in Florida and the West Indies. Key words: Biogeography, biological invasion, exotic species, invasive species. Myrmecol. News 18: 93-97 (online 19 February 2013) ISSN 1994-4136 (print), ISSN 1997-3500 (online) Received 28 November 2012; revision received 7 January 2013; accepted 9 January 2013 Subject Editor: Florian M. -

Technomyrmex Difficilis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the West Indies

428 Florida Entomologist 91(3) September 2008 TECHNOMYRMEX DIFFICILIS (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE) IN THE WEST INDIES JAMES K. WETTERER Wilkes Honors College, Florida Atlantic University, 5353 Parkside Drive, Jupiter, FL 33458 ABSTRACT Technomyrmex difficilis Forel is an Old World ant often misidentified as the white-footed ant, Technomyrmex albipes (Smith). The earliest New World records of T. difficilis are from Miami-Dade County, Florida, collected beginning in 1986. Since then, it has been found in at least 22 Florida counties. Here, I report T. difficilis from 5 West Indian islands: Antigua, Nevis, Puerto Rico, St. Croix, and St. Thomas. Colonies were widespread only on St. Croix. It is probable that over the next few years T. difficilis will become increasingly important as a pest in Florida and the West Indies. Key Words: exotic species, Technomyrmex difficilis, pest ants, West Indies RESUMEN El Technomyrmex difficilis Forel es una hormiga del Mundo Antiguo que a menudo es mal identificada como la hormiga de patas blancas, Technomyrmex albipes (Smith). Los registros mas viejos de T. difficilis son del condado de Miami-Dade, Florida, recolectadas en el princi- pio de 1986. Desde entonces, la hormiga ha sido encontrada en por lo menos 22 condados de la Florida. Aquí, informo de la presencia de T. difficilis en 5 islas del Caribe: Antigua, Nevis, Puerto Rico, St. Croix y St. Thomas. Las colonias solamente fueron muy exparcidas en St. Croix. Es probable que la importancia de T. difficilis como plaga va a aumentar durante los proximos años en la Florida y el Caribe. The white-footed ant, Technomyrmex albipes MATERIALS AND METHODS (Smith), has long been considered a pest in many parts of the world. -

Ants - White-Footed Ant (360)

Pacific Pests and Pathogens - Fact Sheets https://apps.lucidcentral.org/ppp/ Ants - white-footed ant (360) Photo 1. White-footed ant, Technomyrmex species, Photo 2. White-footed ant, Technomyrmex species, tending an infestation of Icerya seychellarum on tending an infestation of mealybugs on noni (Morinda avocado for their honeydew. citrifolia) for their honeydew. Photo 3. White-footed ant, Technomyrmex albipes, side Photo 4. White-footed ant, Technomyrmex albipes, view. from above. Photo 5. White-footed ant, Technomyrmex albipes; view of head. Common Name White-footed ant; white-footed house ant. Scientific Name Technomyrmex albipes. Identification of the ant requires expert examination as there are several other species that are similar. Many specimens previously identified as Technomyrmex albipes have subsequently been reidentified as Technomyrmex difficilis (difficult white-footed ant) or as Technomyrmex vitiensis (Fijian white-footed ant), which also occurs worldwide. Distribution Worldwide. Asia, Africa, North and South America (restricted), Caribbean, Europe (restricted), Oceania. It is recorded from Australia, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Guam, Marshall Islands, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Pitcairn, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Wallis and Futuna. Hosts Tent-like nests made of debris occur on the ground within leaf litter, under stones or wood, among leaves of low vegetation, in holes, crevices and crotches of stems and trunks, in the canopies of trees, and on fruit. The ants also make nests in wall cavities of houses, foraging in kitchens and bathrooms. Symptoms & Life Cycle Damage to plants is not done directly by Technomyrmex albipes, but indirectly. The ants feed on honeydew of aphids, mealybugs, scale insects and whiteflies, and prevent the natural enemies of these pests from attacking them. -

Ergatomorph Wingless Males in Technomyrmex Vitiensis Mann, 1921 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

JHR 53: 25–34 (2016) Ergatomorph wingless males in Technomyrmex vitiensis ... 25 doi: 10.3897/jhr.53.8904 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://jhr.pensoft.net Ergatomorph wingless males in Technomyrmex vitiensis Mann, 1921 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Pavel Pech1, Aleš Bezděk2 1 Faculty of Science, University of Hradec Králové, Rokitanského 62, 500 03 Hradec Králové, Czech Republic 2 Biology Centre CAS, Institute of Entomology, Branišovská 31, 370 05 České Budějovice, Czech Republic Corresponding author: Pavel Pech ([email protected]) Academic editor: M. Ohl | Received 19 April 2016 | Accepted 1 August 2016 | Published 19 December 2016 http://zoobank.org/2EFE69ED-83D7-4577-B3EF-DCC6AAA4457D Citation: Pech P, Bezděk A (2016) Ergatomorph wingless males in Technomyrmex vitiensis Mann, 1921 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of Hymenoptera Research 53: 25–34. https://doi.org/10.3897/jhr.53.8904 Abstract Ergatomorph wingless males are known in several species of the genus Technomyrmex Mayr, 1872. The first record of these males is given inT. vitiensis Mann, 1921. In comparison with winged males, wingless males have a smaller thorax and genitalia, but both forms have ocelli and the same size of eyes. Wingless males seem to form a substantial portion (more than 10%) of all adults in examined colony fragments. Wingless males are present in colonies during the whole year, whereas the presence of winged males seems to be limited by season. Wingless males do not participate in the taking care of the brood and active forag- ing outside the nest. Males of both types possess metapleural gland openings. Beside males with normal straight scapes, strange hockey stick-like scapes have been observed in several males. -

Bioinvasion and Global Environmental Governance: the Transnational Policy Network on Invasive Alien Species China's Actions O

1 Bioinvasion and Global Environmental Governance: The Transnational Policy Network on Invasive Alien Species China’s Actions on IAS Description1 The People’s Republic of China is a communist state in East Asia, bordering the East China Sea, Korea Bay, Yellow Sea, and South China Sea, between North Korea and Vietnam. For centuries China stood as a leading civilization, outpacing the rest of the world in the arts and sciences, but in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the country was beset by civil unrest, major famines, military defeats, and foreign occupation. The claimed area of the ROC includes Mainland China and several off-shore islands (Taiwan, Outer Mongolia, Northern Burma, and Tuva, which is now Russian territory). The current President Ma Ying-jeou reinstated the ROC's claim to be the sole legitimate government of China and the claim that mainland China is part of ROC's territory. The extremely diverse climate; tropical in south to subarctic in north, varies over the diverse terrain, mostly mountains, high plateaus, deserts in west; plains, deltas, and hills in east. After 1978, Deng Xiaoping and other leaders focused on market-oriented economic development and by 2000 output had quadrupled. Economic development has been more rapid in coastal provinces than in the interior, and approximately 200 million rural laborers and their dependents have relocated to urban areas to find work. One demographic consequence of the "one child" policy is that China is now one of the most rapidly aging countries in the world. For much of the population (1.3 billion), living standards have improved dramatically and the room for personal choice has expanded, yet political controls remain tight. -

Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Dolichoderinae) from Colombia

Revista Colombiana de Entomología 37 (1): 159-161 (2011) 159 Scientific note The first record of the genus Gracilidris (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Dolichoderinae) from Colombia Primer registro del género Gracilidris (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Dolichoderinae) para Colombia ROBERTO J. GUERRERO1 and CATALINA SANABRIA2 Abstract: The dolichoderine ant genus Gracilidris and its sole species, G. pombero, are recorded for the first time for Colombia from populations from the foothills of the Colombian Amazon basin. Comments and hypotheses about the biogeography of the genus are discussed. Key words: Ants. Biodiversity. Caquetá. Colombian Amazon. Grazing systems. Resumen: El género dolicoderino de hormigas Gracilidris y su única especie, G. pombero, son registrados por primera vez para Colombia, de poblaciones provenientes del piedemonte de la cuenca Amazónica colombiana. Algunos comen- tarios e hipótesis sobre la biogeografía del género son discutidos. Palabras clave: Hormigas. Biodiversidad. Caquetá. Amazonas colombiano. Pasturas ganaderas. Introduction distribution of the genus Gracilidris in South America. We also discuss each of the dolichoderine genera that occur in Currently, dolichoderine ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Colombia. Dolichoderinae) include 28 extant genera (Bolton et al. 2006; Fisher 2009) distributed in four tribes according to Methods the latest higher level classification of the ant subfamily Dolichoderinae (Ward et al. 2010). Eleven of those extant We separated G. pombero specimens from all ants collected genera occur in the New World: Bothriomyrmex, Dolicho- in the project “Amaz_BD: Biodiversidad de los paisajes derus, Liometopum, Tapinoma, and Technomyrmex have a Amazónicos, determinantes socio-económicos y produc- global distribution, while Anillidris, Azteca, Dorymyrmex, ción de bienes y servicios”. This research was carried out in Forelius, Gracilidris, and Linepithema are endemic to the Caquetá department located in the western foothills of the New World. -

WHITEFOOTED ANT Scientific Names: Technomyrmex Albipes, T

WHITEFOOTED ANT Scientific names: Technomyrmex albipes, T. difficilis, T. vitiensis Order: Hymenoptera Family: Formicidae Common name: whitefooted ant DESCRIPTION Adults have different body types according to their role in the colony . Adult workers are females, wingless, 2 to 4 mm (< ¼ “) long, and dull black with yellowish‐white lower legs. Queens are larger, winged early in life, and lay fertile and infertile eggs Actual size throughout their lives. Males are wingless, short‐lived, and function only in reproduction. DAMAGE . Damage by whitefooted ants (WFA) is usually indirect since they tend honeydew‐producing insects (mealybugs, aphids, soft scales, whiteflies), protecting them from control by natural enemies. Although WFA are strongly attracted to sweet foods, such as plant nectar and honeydew, they also feed on decaying plant and animal tissue. WFA are a nuisance to homeowners as they forage indoors and outdoors, attracted by food and electrical contacts. LIFE CYCLE / BEHAVIOR The lifespan of worker ants is not known, but queens can live more than a year. Eggs are tiny (.5 mm), white or yellowish , oval, and are found, along with other developmental stages, in the nest constructed of dirt and plant debris (such as red ginger flowers). Young larvae are legless, pale, and shaped like a crook‐ necked gourds (heads at smaller, narrow end). Larvae develop into pupae without cocoons; both pupae and larvae are often mistaken for eggs. Whitefooted ants are very difficult to control because they do not exchange baits orally. If the majority of workers feed on the bait and die, the rest of the colony will eventually die of starvation. -

Revista Entomologia 34 Final.P65

110Revista Colombiana de Entomología 34 (1): 110-115 (2008) Technomyrmex (Formicidae: Dolichoderinae) in the New World: synopsis and description of a new species Technomyrmex (Formicidae: Dolichoderinae) en el Nuevo Mundo: sinopsis y descripción de una nueva especie FERNANDO FERNÁNDEZ1 and ROBERTO J. GUERRERO2 Abstract: A synopsis of dolichoderine ants of the genus Technomyrmex Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the New World is offered including notes, keys, pictures of all known species, and the description of T. gorgona sp. n. from SW Colombia. This is the first record of the genus from continental South America. Currently Technomyrmex comprises six species (two extinct, marked by *) in the New World: *T. caritatis Brandão & Baroni Urbani (Dominican amber), T. difficilis Forel (tramp species collected in Washington, Puerto Rico, Antigua and Nevis), T. fulvus (Wheeler) (Costa Rica, Panama and Colombia), T. gorgona n. sp. (Colombia), the first record for Colombia and South America, *T. hispaniolae (Wilson) (Dominican amber) and T. vitiensis Mann (tramp species collected in California). Key words: Ants. South America. Taxonomy. Technomyrmex. Resumen: Se ofrece una sinopsis de las hormigas dolichoderinas del género Technomyrmex Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), incluyendo notas, claves, fotografías para todas las especies conocidas en el Nuevo Mundo, y la descrip- ción de T. gorgona sp. n. del SO de Colombia. Este es el primer registro del género para la parte continental de América del Sur. Actualmente, Technomyrmex está constituido por seis especies (dos extintas, indicadas con un *) en el Nuevo Mundo: *T. caritatis Brandão & Baroni Urbani (ámbar dominicano), T. difficilis Forel (especie introducida recolectada in Washington, Puerto Rico, Antigua y Nevis), T. -

Recent Human History Governs Global Ant Invasion Dynamics

ARTICLES PUBLISHED: 22 JUNE 2017 | VOLUME: 1 | ARTICLE NUMBER: 0184 Recent human history governs global ant invasion dynamics Cleo Bertelsmeier1*, Sébastien Ollier2, Andrew Liebhold3 and Laurent Keller1* Human trade and travel are breaking down biogeographic barriers, resulting in shifts in the geographical distribution of organ- isms, yet it remains largely unknown whether different alien species generally follow similar spatiotemporal colonization patterns and how such patterns are driven by trends in global trade. Here, we analyse the global distribution of 241 alien ant species and show that these species comprise four distinct groups that inherently differ in their worldwide distribution from that of native species. The global spread of these four distinct species groups has been greatly, but differentially, influenced by major events in recent human history, in particular historical waves of globalization (approximately 1850–1914 and 1960 to present), world wars and global recessions. Species in these four groups also differ in six important morphological and life- history traits and their degree of invasiveness. Combining spatiotemporal distribution data with life-history trait information provides valuable insight into the processes driving biological invasions and facilitates identification of species most likely to become invasive in the future. hallmark of the Anthropocene is range expansion by alien been introduced outside their native range). For each species, we species around the world1, facilitated by the construction of recorded the number of countries where it had established (spatial transport networks and the globalization of trade and labour richness) and estimated spatial diversity taking into account pair- A 2 16 markets since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution . -

The Composition of Ant Species on Banana Plants with Banana Bunchy-Top Virus (BBTV) Symptoms in West Sumatra, Indonesia

ASIAN MYRMECOLOGY Volume 5, 151–161, 2013 ISSN 1985-1944 © HENNY HERWINA , NASRIL NASIR , JUM J UNIDANG AND YA H ERWANDI The composition of ant species on banana plants with Banana Bunchy-top Virus (BBTV) symptoms in West Sumatra, Indonesia. HENNY HERWINA 1*, NASRIL NASIR 1, JUM J UNIDANG 2 AND YA H ERWANDI 3 1Department of Biology, Faculty of Mathematic and Natural Sciences, Andalas University, Indonesia. 2Indonesian Tropical Fruit Research Institute. Jl.Raya Solok Aripan km 8, Solok, West Sumatra, Indonesia. 3Department of Pest and Plant Pathology, Faculty of Agriculture, Andalas University, Padang, West Sumatra, 25163, Indonesia. *Corresponding author's email: [email protected] ABSTRACT. A brief study on ant species on banana plants with Banana Bunchy-top Virus (BBTV) symptoms was conducted by direct collection in four regencies and one city of West Sumatra Province in Indonesia. During the sampling we found 39 banana plants with BBTV symptoms, of which36 were occupied by insects, and of these 35 plants contained ants. A total of 24 species of ants, belonging to 16 genera, were collected. Myrmicinae was the subfamily with the highest number of species (11), followed by Formicinae (seven) and Dolichoderinae (six). Tetramorium and Technomyrmex were the genera with the most species (four). Dolichoderus thoracicus was found most frequently among samples, accounting for16% of species occurrences, followed by Tapinoma melanocephalum and Paratrechina longicornis (11 and 10% respectively). Seventeen species of ants were found associated with aphids of which six showed a statistically-significant association, while seven ant species were not observed with trophobionts. Species that were found more often associated with aphids were found more frequently during the study. -

Science Review 2013

Science Review 2013 Research using data accessed through the Global Biodiversity Information Facility Foreword When surveying the growing number of papers making use of GBIF-mobilized data, one thing that is striking is the breadth of geographic, temporal, and taxonomic scale these studies cover. GBIF-mobilized data is relevant to surveying county- level populations of velvet ants in Oklahoma, to predicting the impact of climate change on the distribution of invasive species, and to determining the extent to which humanity has made innovative uses of the biosphere as measured by the biodiversity of patent applications. All of these applications rely on both the quality and quantity of the data that are available to biodiversity researchers. Within the wider scientific community the theme of data citation is gaining wider prominence, both as a means to give credit to those who create and curate data, and to track the provenance of data as they are used (and re-used). Many of the papers listed in this report come with Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) that uniquely identify each publication, which facilitates tracking the use of each paper (for example through citations by other publications, or other venues such as online discussions and social media). Initiatives to encourage ‘data papers’ in online journals, such as those produced by Pensoft Publishers (see p41), are associating DOIs with data, so that data no longer are the poor cousins of standard research papers. One thing I look forward to is seeing DOIs attached directly to GBIF-mobilized data, so that we can begin to track the use of the data with greater fidelity, providing valuable feedback to those who have seen the value of GBIF and have contributed to GBIF’s effort to enable free and open access to biodiversity data.