The Psychology of Puppy Play: a Phenomenological Investigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bondage and Discipline, Dominance and Submission, and Sadomasochism (Bdsm)/Kink

BONDAGE AND DISCIPLINE, DOMINANCE AND SUBMISSION, 6 AND SADOMASOCHISM (BDSM)/KINK Brian is a white gay man of 55 who has been working with you in therapy for several sessions on the panic attacks and nightmares he has been expe- riencing following witnessing a person committing suicide at a tube sta- tion some months ago. For a couple of weeks you have sensed that there are some aspects of his life that he hasn’t been completely open about with you. At the end of a session he looks uncomfortable and says that there is something he has to tell you which he hopes won’t influence your opinion of him but which has been holding him back from talking about all aspects of his life. He says that he is in a 24/7 BDSM relationship as a slave for his partner, Jordan. Think about: • What is your formulation/understanding of the key issues for Brian? • What themes can you imagine emerging as you continue? • What assumptions might you bring to this? • How would you proceed? Being a kink-aware professional you let Brian know that you have some understanding of BDSM practices and relationships. He has probably already seen SM 101 and Powerful Pleasures on your bookshelf, and that probably helped him to tell you about this aspect of his life. Like many people, the idea of ‘24/7’ BDSM is one that you find difficult to understand, so you note your negative gut reaction as one you want to bracket as much as possible and explore in supervision. -

Sadomasochist Role-Playing As Live- Action Role-Playing: a Trait-Descriptive Analysis

International Journal of Role-Playing - Issue 2 Sadomasochist Role-Playing as Live- Action Role-Playing: A Trait-Descriptive Analysis Popular Abstract - This article describes sadomasochist role-playing which is physically performed by its participants. All sadomasochist activities have a role-playing component to them. It is a form of role-playing where people consensually take on dominant and submissive roles, for the purpose of inflicting things such as pain and humiliation, in order to create pleasure for all participants. In some cases, participants agree to emphasize those roles, or make them fetishistically attractive, by adding complexity and definitions to them, and then act them out in semi-scripted fantasy scenes. This paper examines that activity, commonly called “sadomasochistic role-play”, as opposed to the more generic “sadomasochism” of which it is only one facet. Furthermore, the article compares this form of play with live-action role-playing (larp). Its main emphasis is on the question of how closely related the two activities are. To determine this, the article examines sadomasochist role-playing as being potentially a game, the question of its goal-orientation and the issue of whether or not it contains a character in the sense of a live-action role-playing character. Based on this process, it comes to the conclusion that sadomasochist role-playing is not a separate type of role-playing, but rather one kind of live-action role-playing. As its theoretical framework, this text utilizes studies done on both live-action role-playing games and on sadomasochist role-playing. Reliable material on the latter being quite limited, descriptions have been gathered from both academic works and practical manuals. -

Skip to Content CLARE BAYLEY Posted on June 27, 2013 33

Skip to Content SFW CLARE BAYLEY Posted on June 27, 2013 33 comments A field guide to Pride flags It’s almost time for SF Pride, and that means the city is sprouting rainbow flags like flowers in the desert after a rainstorm. By now most people know what the rainbow signifies, but what about those other striped flags you see waving at Pride events? I thought I knew most of their meanings, but I recently came across the most Pride items I’ve ever seen in one place, and they had keychains with flags that I’d never seen before (and my office is a castle that flies Pride flags from the turrets). Here’s a quick overview of all the ones I could find online, plus a more detailed history and analysis for each further down. My sources are cited in-line or listed at the end. The top 3 are the ones most commonly seen at Pride events. Edited on 6/27/15: Updated/added some flags based on reader feedback. Rearranged flag order to loosely group by category. The Gay Pride Rainbow Ah, the rainbow flag. Such a beautiful and bold statement, hard to ignore or mistake for anything else. (also easy to adapt to every kind of merchandise you can imagine) Wikipedia has an extensive article on it, but here are the more interesting bits: The original Gay Pride Flag was first flown in the 1978 San Francisco Pride Parade, and unlike its modern day 6- color version it was a full rainbow – it included hot pink, turquoise, and indigo instead of dark blue. -

Rob of Amsterdam Leather Fashion Designer His Last Video Interview: June 21, 1989

©Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. Pre-Publication Web Posting 219 THE MAN WHO MADE THE CLOTHES THAT MAKE THE MAN Rob of Amsterdam Leather Fashion Designer His Last Video Interview: June 21, 1989 On June 21, 1989, Rob Meijer, who died in 1990, took time from his busy Wednesday afternoon to sit for a video interview in his office above his Rob of Amsterdam couture shop and art gallery. I had first visited Amsterdam in 1969, rooming wantonly above the Argos Bar, but this was different. It was Holland at the height of the AIDS pandemic, two months after Drummer publisher Anthony DeBlase designed the leather pride flag, three months after the death of leather fashion photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, four months before the earthquake that destroyed the Drummer office, and five months before the fall of the Berlin Wall. Everyone was on edge. Turmoil was in the air. Rob received me and Mark Hemry, my husband and creative partner of ten years, because we were from Drummer, which was very much a leather fashion magazine. Just two hours before, we San Francisco leathermen had landed at Schiphol Airport. We had been flown in by Roger Earl and Terry Legrand, the pioneer filmmakers of the 1975 leather classic Born to Raise Hell. Because they liked how we directed and shot leather features for our Palm Drive Video studio, they had hired us onto their other- wise European film crew as cameramen to do a two-camera shoot for six S&M video features for their Marathon Studio based in Los Angeles. It was Terry who had convinced Rob to sit for our interview, which Mark shot. -

AMERICAN INFERNO by PATRICK DENKER

AMERICAN INFERNO by PATRICK DENKER (Under the Direction of Reginald McKnight) ABSTRACT American Inferno, a novel, is a loose transposition of Dante‟s Inferno into a contemporary American setting. Its chapters (or “circles”) correspond to Dante‟s nine circles of Hell: 1) Limbo, 2) Lust, 3) Gluttony, 4) Hoarding & Wasting, 5) Wrath, 6) Heresy, 7) Violence, 8) Fraud and 9) Treachery. The novel‟s Prologue — Circle 0 — corresponds to the events that occur, in the Inferno, prior to Dante‟s and Virgil‟s entrance into Hell proper. The novel is a contemporary American moral inquiry, not a medieval Florentine one: thus it is sometimes in harmony with and sometimes a critique of Dante‟s moral system. Also, like the Inferno, it is not an investigation just of its characters‟ personal moral struggles, but also of the historical sins of its nation: for Dante, the nascent Italian state; for us, the United States. Thus the novel follows the life story of its principal character as he progresses from menial to mortal sins while simultaneously considering American history from America‟s early Puritan foundations in the Northeast (Chapters 1-4) through slavery, civil war and manifest destiny (Chapters 5-7) to its ultimate expression in the high-technology West-Coast entertainment industry (Chapters 8-9). INDEX WORDS: Dante Alighieri, Divine Comedy, Inferno, Sin, American history, American morality, Consumerism, Philosophical fiction, Social realism, Frame narrative, Christianity, Secularism, Enlightenment, Jefferson, Adorno, Culture industry, lobbying, public relations, advertising, marketing AMERICAN INFERNO by PATRICK DENKER B.A., Duke University, 1992 M.F.A., San Francisco State University, 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ATHENS, GEORGIA 2010 © 2010 Patrick Denker All Rights Reserved AMERICAN INFERNO by PATRICK DENKER Major Professor: Reginald McKnight Committee: O. -

ENEGADE IP 'J.JV.JYJ.J, Therip

. .,· .---· , . ..· Protests . , . co.ntinue. \ •' .. ' . ;~..-- · hn1nigrati,,u ,·;·,11~ ai \l!lrtio Lu&hcr .~in~ Park 01, ( ·~,ar Cha\·~, D.t}. ) ... --. l .. · · 1 · News, Page 3 J ' , I . ' • • ot • • I - ·' ENEGADE IP 'J.JV.JYJ.J, therip. com Vol. 78 • No. 5 Bakersfield College Apri! 11, 2007 I Burgl~r • BC students voted for their caught by representatives in the Student Government Association during Spring Fling week lv1arch 26-Ma.cch 30. security By TAYLOR M. GOMBOS tgombo~baJ:.ersfiela'college.edu Rip staff writer • Car burglary suspect appprehended by. campus public Attention students of Bakmfield College: You have a safety officers in the parking lot new leader. John Lopez, BC computer science major, defeated the on M~.rch 21. SGA veteran Alan Crane to win the presidency of me Stu dent Government Association. · . By ~'YLE BEALL Lopez defeated Crane by securi.ag 66% (364 votes) of kbeall@bakersfieldc(}//ege.edu Rip staff \•.triter i.;~ \v.¢:i wailc U.llltc ouly ~-ureo 33.3% (184 votes) of the Votes. Crane said that he was a little swprised by the 66% mar' A burglary suspcc-t was apprehended and ar gin oot added. "'ibe students have spoken and said that the!' rested on the po.rt.ing lot at the northeast side of , 1;llffipo5 three Wllllt John as a president. I am sure he will do a fine job. He for felony count$ of car burglary, including one felooy count of possession of will have the support of a team whlch is absolutely ~ moo burglary qualified exocuti~ team ever put together Ill BC." tools end a felony coont of grand theft Cnne, who cwn:ntly seTYes as .legislatiYc liaison of the auto, SGA aw ~It of the statewide ·suadent senate, lklded The arrest .,.,as made on campus by 8~Ll College public safety officers after IY',..e of the of tb.l.t be is planning 10 go back to being a regular sni&:nt when his Sfll1c term is up in J\D'le. -

Ten Lies About Sadomasochism by Melissa Farley

Ten Lies About Sadomasochism by Melissa Farley, 10/9/2003, sur le site de Media Watch, publié dans Sinister Wisdom1 #50, Summer/Fall 1993 pages 29-37 1. Pain is pleasure; humiliation is enjoyable; bondage is liberation. 2. Sadomasochism is love and trust, not domination and annihilation. 3. Sadomasochism is not racist and anti Semitic even though we “act” like slave owners and enslaved Africans, Nazis and persecuted Jews. 4. Sadomasochism is consensual; no one gets hurt if they don’t want to get hurt. No one has died from sadomasochistic “scenes.” 5. Sadomasochism is only about sex. It doesn’t extend into the rest of the relationship. 6. Sadomasochistic pornography has no relationship to the sadomasochistic society we live in. “If it feels good, go with it.” “We create our own sexuality.” 7. Lesbians “into sadomasochism” are feminists, devoted to women, and a women-only lesbian community. Lesbian pornography is “by women, for women.” 8. Since lesbians are superior to men, we can “play” with sadomasochism in a liberating way that heterosexuals can not. 9. Reenacting abuse heals abuse. Sadomasochism heals emotional wounds from childhood sexual assault. 10. Sadomasochism is political dissent. It is progressive and even “transgressive” in that it breaks the rules of the dominant sexual ideology. Although formulated by its current advocates as an issue of sexual liberation, minority rights, or even healing, I consider lesbian sadomasochism to be primarily an issue of feminist ethics. I believe that lesbians who embrace sadomasochism either theoretically or in practice, are supporting the lifeblood of patriarchy. “The symbols, language and style of lesbian sadomasochist chic are the symbols, language and style of male supremacy: violation, ruthlessness, intimidation, humiliation, force, mockery, consumerism.” (De Clarke, 1993) Choosing sadomasochism, given our oppression, is an act of profound betrayal. -

2021-001853Des

Landmark Designation REcommendation Executive Summary HEARING DATE: May 19, 2021 Record No.: 2021-001853DES Project Address: 396-398 12th Street (San Francisco Eagle Bar) Zoning: WMUG WESTERN SOMA MIXED-USE GENERAL 55-X Height and Bulk District Block/Lot: 3522/014 Project Sponsor: Planning Department 49 South Van Ness Avenue, Suite 1400 San Francisco, CA 94103 Property Owner: John Nikitopoulos P.O. Box 73 Boonville, CA 95415 Staff Contact: Alex Westhoff 628-652-7314 [email protected] Recommendation: Recommend Landmark Designation to the Board of Supervisors Property Description The subject site lies on an approximately 5,153 square feet, irregularly-shaped rectangular lot at the corner of 12th and Harrison Streets with approximately 79.5 feet of street frontage along 12th Street, and 60.5 feet along Harrison Street. The property includes both indoor and outdoor components including the main corner building with indoor bar, stage, DJ booth, and an indoor/outdoor bar, and a spacious patio with stage; and a rear building with an enclosed bar, walk-in cooler, and storage. Exterior The building is comprised of multiple structures with varying roof forms. The corner one-story building with gabled roof, which houses the front indoor bar space includes a northeast facing primary elevation roughly 22 feet in length with three structural bays (12th Street elevation). The wood-framed building has no discernable architectural style and includes scored stucco cladding along the front façade. Front façade fenestration includes a segmented arched opening with a recessed primary entryway, solid double entry doors with a glazed transom, and a scored concrete step. -

Kink Negotiation & Scene Planning Tools

Kink Negotiation & Scene Planning Tools ROUGH BS Pre-Scene Planning Tool ROUGH BS is a proprietary preliminary BDSM negotiation tool. The acronym stands for Restrained, Owned, Used, Given Away, Humiliated, Beaten, Serve. Its purpose is to outline the general categories of play you and your scene partners most enjoy. This can help determine overall compatibility with prospective play partners. It can also help you pinpoint which foundational elements to build your scene around. This tool is a conversation prompt. To use it, determine how much you enjoy engaging in each category of activities as either a bottom or top (the bottom would be the subject of these actions and the top would be executing them). Use a 1-10 scale with 1 being “not interested” and 10 being “YES!” Let’s say two partners score high on “Given Away.” Go further to ask clarifying questions like “what does that mean to you?” In this example, being given away could mean to another dominant you both know well for an hour of domestic service. Or it could mean to a group of five people for sexual pleasure every Tuesday. Because these categories are broad, ambiguous, and subjective, further negotiation under each is mandatory. The Yes/No/Maybe list below can help you drill down to specific activities that fall under each category for more nuanced negotiation. Kink Yes/No/Maybe List A Yes/No/Maybe list is a kink/sexual inventory checklist designed to aid in self-analysis and/or partner negotiations. You can use it several ways: ● Mark beside each YES (what you want to do), MAYBE (soft limit), or NO (hard limit) and talk through each with your partner. -

Massive Bdsm Checklist

MASSIVE BDSM CHECKLIST Legend for Experience Legend for Limits/Interest Don't be afraid to modify the rankings as needed, or to even put 0 - No Answer 0 - Hard Limit (Not willing at all) something else in a space. Like NEVER or N/A or whatever you need. 1- No Experience/No Interest 1 - Neutral/Uninterested 2 - No Experience/Interested or 2 - May try for partner curious 3 - Willing to try/Have tried but not my 3 - A Little Experience favorite thing 4 - Some Experience 4 - Like It 5 - A Lot of Experience 5 - Love It Feel free to use markers for certain items. (Like red for a ABSOLUTE hard limit, green for YES, PLEASE, and yellow/orange for CAUTION.) Use Comments section for notes. Bondage and Suspension Activity Experience Limits/Interest Comments Blindfolds Bondage (heavy) Bondage (light) Immobilization Bondage (public, under clothing) Leather restraints Chains Ropes Japanese rope bondage Western rope bondage Rope body harness Arm & leg sleeves (armbinders) Harnesses (leather) Harnesses (rope) Collar (leather) Collar (chain) Collar (solid metal) Collar (day) Leash/lead Cuffs (leather) Cuffs (metal) Manacles & Irons Suspension cuffs - hands Suspension cuffs - feet Gags (cloth) Gags (rubber) Gags (tape) Gags (phallic) Gags (ring) Gags (ball) Gags (bit) Gags (spider) Gags (ashtray, duster, other) Mouth bits Full head hoods - leather Full head hoods - latex Full head hoods - spandex/lycra Hood - animal play Partial head hood Face mask Mummification/plastic wrap Vaccu bed/cube Straight jacket Sleep sack Suspension (upright) Suspension (horizontal) Suspension (inverted) Impact/Percussion Activity Experience Limits/Interest Comments Spanking Flogging (general) Floggers - fluffy bunny Floggers - mop/suede Floggers - leather Floggers - braided/stiff Floggers - stingy Floggers - severe Single-tail whips Canes - rattan Canes - metal Canes - other Belts Leather straps Riding crops Hairbrushes Wooden paddles Metal paddles Acrylic/nylon paddles Misc. -

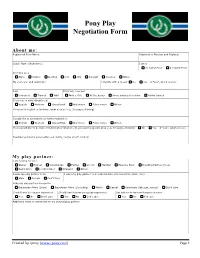

Pony Play Negotiation Form (PDF)

Pony Play Negotiation Form About me: Registered Pony Name: Registration Number and Registry: Stable Name (Nickname): I am a 2 Legged Pony 4 Legged Pony I identify as a Mare Stallion Gelding Colt Filly Ponygirl Ponyboy Other: My coat color and markings: I identify with a breed No Yes If “yes”, which one(s): I am If trained, how well Untrained Trained Wild Only a little All the basics Some advanced training Highly trained If trained, in what discipline(s) English Western Circus/Trick War Horse Police Horse Other: If trained in English or Western, what area(s) (e.g. Dressage, Reining): I would like to be trained (or further trained) in English Western Circus/Trick War Horse Police Horse Other: If you would like to be trained in English or Western, do you want a specific area (e.g. Dressage, Reining) No Yes If “yes”, which one(s): Describe your pony personality (e.g. feisty, “bomb proof”, loving): My play partner: I am looking for a(n) Owner Trainer Veterinarian Farrier Groom Handler Exercise Rider Breeding Partner (Pony) Alpha Mare Herd Member Wrangler Other: I want my play partner to be I want my play partner to be (affectionate, fair-but-strict, strict, etc.): Male Female Don’t Care I like my play partner dressed in Equestrian Attire (Show) Equestrian Attire (Schooling) Fetish Casual Veterinary (lab coat, scrubs) Don’t Care Should have bio-equine experience Should have human pony play experience Can ask me to try new things in a scene Yes No Don’t care Yes No Don’t care Yes No Yes, but: Additional notes or comments on my desired play partner: -

Sadomasochism

Dignity: A Journal on Sexual Exploitation and Violence Volume 3 | Issue 2 Article 2 March 2018 Sadomasochism: Descent into Darkness, Annotated Accounts of Cases, 1996-2014 Robert Peters Morality in Media & National Center on Sexual Exploitation, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/dignity Part of the Applied Behavior Analysis Commons, Clinical Psychology Commons, Community- Based Research Commons, Courts Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Criminology Commons, Domestic and Intimate Partner Violence Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Judges Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Law and Society Commons, Sexuality and the Law Commons, Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Peters, Robert (2018) "Sadomasochism: Descent into Darkness, Annotated Accounts of Cases, 1996-2014," Dignity: A Journal on Sexual Exploitation and Violence: Vol. 3: Iss. 2, Article 2. DOI: 10.23860/dignity.2018.03.02.02 Available at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/dignity/vol3/iss2/2https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/dignity/vol3/iss2/2 This Resource is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dignity: A Journal on Sexual Exploitation and Violence by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sadomasochism: Descent into Darkness, Annotated Accounts of Cases, 1996-2014 Abstract A collection of accounts of sadomasochistic sexual abuse from news reports and scholarly and professional sources about the dark underbelly of sadomasochism and the pornography that contributes to it. It focuses on crimes and other harmful sexual behavior related to the pursuit of sadistic sexual pleasure in North America and the U.K.