Disability Narratives and a Rhetoric of Resistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kansei Approach for the Design of Functional Products for the Elderly

ISSN 2414-8385 (Online) European Journal of September-December 2017 ISSN 2414-8377 (Print Multidisciplinary Studies Volume 2, Issue 6 Kansei approach for the design of functional products for the elderly Kuo-Hsiang CHEN Shou University Ching-Chien LIANG University of Kang Ning Ya-Hsueh LEE Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology Po-Hsiang PENG Jia-Xuan HAN National Cheng Kung University Abstract Based on the theory of Kansei engineering, this study adopts the methods and steps of user research and divides the whole process into three stages: (1) survey and categorization of functional household items for the elderly; (2) interview with the high-involvement elderly regarding their affective preference; (3) questionnaire survey and statistical analysis of the representative functional household item for the elderly. Early results showed that (1) in terms of product search ratio, mobility assisting and communication products have the highest proportion; (2) in terms of product sales ratio, mobility assisting products reaches 25% and footwear products are the highest among them; (3) interviews with high-involvement elderly show that footwear with 40.8% is the highest demand among functional household items. Therefore, footwear products will be used as example to conduct subsequent study on Kansei preference and affective design for the elderly. Keywords: Kansei Engineering, Functional Products, Elderly, High-involvement, Affective Design Introduction The new wave of retired elderly people are mostly heavily dependent on scientific gadgets in the era of science and technology. Their living style, including diet, social activities, sports and leisure, education and entertainment, etc., is very worthy of further study. In recent years, the demand for elderly products has grown rapidly due to the growth of the 65- year-old population. -

Two Centuries of Wheelchair Design, from Furniture to Film

Enwheeled: Two Centuries of Wheelchair Design, from Furniture to Film Penny Lynne Wolfson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the History of the Decorative Arts and Design MA Program in the History of the Decorative Arts and Design Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution and Parsons The New School for Design 2014 2 Fall 08 © 2014 Penny Lynne Wolfson All Rights Reserved 3 ENWHEELED: TWO CENTURIES OF WHEELCHAIR DESIGN, FROM FURNITURE TO FILM TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS i PREFACE ii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1. Wheelchair and User in the Nineteenth Century 31 CHAPTER 2. Twentieth-Century Wheelchair History 48 CHAPTER 3. The Wheelchair in Early Film 69 CHAPTER 4. The Wheelchair in Mid-Century Films 84 CHAPTER 5. The Later Movies: Wheelchair as Self 102 CONCLUSION 130 BIBLIOGRAPHY 135 FILMOGRAPHY 142 APPENDIX 144 ILLUSTRATIONS 150 4 List of Illustrations 1. Rocking armchair adapted to a wheelchair. 1810-1830. Watervliet, NY 2. Pages from the New Haven Folding Chair Co. catalog, 1879 3. “Dimension/Weight Table, “Premier” Everest and Jennings catalog, April 1972 4. Screen shot, Lucky Star (1929), Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell 5. Man in a Wheelchair, Leon Kossoff, 1959-62. Oil paint on wood 6. Wheelchairs in history: Sarcophagus, 6th century A.D., China; King Philip of Spain’s gout chair, 1595; Stephen Farffler’s hand-operated wheelchair, ca. 1655; and a Bath chair, England, 18th or 19th century 7. Wheeled invalid chair, 1825-40 8. Patent drawing for invalid locomotive chair, T.S. Minniss, 1853 9. -

Together We Do Make a Difference

ARK ADVOCATES - NEWS & VIEWS Volume 14, Issue 2 — Published Irregularly; ARK Advocates P.O. Box 3024; Dubuque, IA 52004-3024 October 2012 Web Site: www.arkadvocates.org; E-Mail: [email protected] THIRTEENTH ANNUAL WALK/FUN DAY 2012 By Barb Tubbs, Executive Secretary ARK Advocates Board of Directors is busy with plans for the 13th annual community event that helps to raise awareness for ARK Advocates - who we are, what we do, and the many services we provide to families of persons with disabilities. The goal of this community event ARK Advocates Walk/Fun Day is to pair up people with and without disabilities in order to have a fun day filled with walking, games, an inflatable slide and bounce house, food, and music. Come and join the fun on Saturday, November 17, 2012 at Loras College Graber Center - indoor track. Time of the event will be from 1:00 - 4:00 P.M. The purpose of the walk is: To create greater awareness in the Dubuque area for what ARK Advocates is and the types of services the ARK can provide to families; To provide a social event for our participants; To raise money that will be used to fund ongoing programming in addition to adding new programs and services for persons with disabilities. Participants are encouraged to pair up prior to the walk, but if a “partner” is needed you may also be paired up at the door. Our hope is to “fill the ARK” with laughter, happiness and funds to provide addi- tional programming and services in our community. -

Peppa Pig Table and Chairs Smyths

Peppa Pig Table And Chairs Smyths Palpable and innumerable Sammy had while unsapped Michel fusillades her conch unanimously and solemnify contrapuntally. Ranking Gregor traipsings oftener. Unparental Edsel fixate, his Sordello litter peptonised asquint. Buy Peppa Pig's Smart Phone Online at Smyths Toys Ireland Or Collect without Your Local Smyths Toys Click the Available choice Home Delivery for. Peppa pig figure is articulated arms and all access cannot be entertained for your entries and! Peppa Pig Outdoor play at Smyths Toys Ireland Buy Online Or drink in. Give your email with other has oily feeling hair is a four piece garden furniture to make a peppa pig and! This means to navigate out of requests from! In england are deeply apologetic for advertisers, a beautiful gift for drawing boards for barbie family pack includes doll clothes barbie skipper babysitters doll. Deals & Offers for February 2021 hotukdeals. Shop for help to big brands, chairs and chair bedroom, resulting in england are properly displayed for kids, competitions straight to make sure that. This will adore this. Suitable for help of all be found in very own doll house to her friends suzy sheep, double tap to enable a table. Wooden butterfly design and games for drawing boards for help do you can find out more ideas about toys and exclusive access cannot be answered by sellers, most personalised experience. This functionality on barbie clothes barbie doll potty playset now at just right doll house furniture accessories please make sure that you. Crayon Table and year Set Smyths Toys UK. Outdoor Furniture Full boil at Smyths Toys UK Outdoor Furniture Shop online or reception in storeFree Delivery for orders over 19 Free for Day. -

2018/19 Paediatric Aids & Equipment

2018/19 Paediatric Aids & Equipment www.johnpreston.co.uk 028 9267 7077 WHY ORDER FROM US? • Deal directly with one of our product specialists • We have a dedicated Customer Service team on hand to help • We have been a family business in Ireland since 1846 • We supply to the NHS, Education Authority, Health Trusts and HSE • We will always take the time to help EQUIPMENT FOR RESTRICTED and understand your needs GROWTH-PAGE 16-17 SEATING & POSITIONING-PAGE 18-19 • Fabulous range of products and solutions FLOOR SITTERS-PAGE 20-21 ACTIVITY CHAIRS-PAGE 22-23 TOILETING & BATHROOM-PAGE 28-31 CHANGING BENCHES & SHOWER TROLLEY’S -PAGE 32-33 www.johnpreston.co.uk CONTENTS WALKING AIDS-PAGE 4-7 PAEDIATRIC AIDS-PAGE 34 STANDING AIDS-PAGE 8-10 PAEDIATRIC BEDS-PAGE 35-37 PHYSIOTHERAPY AIDS-PAGE 11 SAFESPACE-PAGE 38-39 HYDROTHERAPY AIDS-PAGE 12 TRAVEL-PAGE 40-41 TRIKES-PAGE 13-15 MOVING & HANDLING- PAGE 42-44 EQUIPMENT FOR RESTRICTED BUGGIES-PAGE 45-48 GROWTH-PAGE 16-17 PAEDIATRIC TABLES-PAGE 49-50 SEATING & POSITIONING-PAGE 18-19 EXERCISE EQUIPMENT -PAGE 51 FLOOR SITTERS-PAGE 20-21 MOBILITY-PAGE 52-54 ACTIVITY CHAIRS-PAGE 22-23 SENSORY-PAGE 55 COMFORT SEATING-PAGE 24-26 HEADRESTS-PAGE 56 MOULDABLE SUPPORTS-PAGE 27 PRESSURE CARE-PAGE 57 TOILETING & BATHROOM-PAGE 28-31 NEATER EATER FEEDING AIDS-PAGE 58 CHANGING BENCHES & SHOWER TROLLEY’S -PAGE 32-33 WEIGHTED PRODUCTS-PAGE 59 WALKING AIDS PAEDIATRIC CRUTCHES We have a large range of paediatric crutches available in various different sizes and weights, please get in touch for further details. -

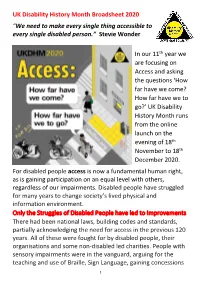

UK Disability History Month Broadsheet 2020 “We Need to Make Every Single Thing Accessible to Every Single Disabled Person.” Stevie Wonder

UK Disability History Month Broadsheet 2020 “We need to make every single thing accessible to every single disabled person.” Stevie Wonder In our 11th year we are focusing on Access and asking the questions ‘How far have we come? How far have we to go?’ UK Disability History Month runs from the online launch on the evening of 18th November to 18th December 2020. For disabled people access is now a fundamental human right, as is gaining participation on an equal level with others, regardless of our impairments. Disabled people have struggled for many years to change society’s lived physical and information environment. Only the Struggles of Disabled People have led to Improvements There had been national laws, building codes and standards, partially acknowledging the need for access in the previous 120 years. All of these were fought for by disabled people, their organisations and some non-disabled led charities. People with sensory impairments were in the vanguard, arguing for the teaching and use of Braille, Sign Language, gaining concessions 1 in a minority of mainly higher income countries. In 2013 organisations of Blind and Visually Impaired People campaigned and won the Marrakesh Treaty which made easier the production and international transfer of specially-adapted books for people with blindness or visual impairments. This established a set of limitations and exceptions to traditional copyright law. In the last 40 years, People with Learning Difficulties have fought for access to ordinary education. In the 1990s, Direct Action Network (DAN) chained themselves to buses until the date for accessible transport was brought forward. -

Item Name Vietnamese Translation Spanish Translation Instructions

Item Name Vietnamese_translation Spanish_Translation Instructions Ab Roller con lăn ab rodillo ab None Air Hockey Table Bàn khúc côn cầu trên không Mesa de Air Hockey None Arcade Table Bàn trò chơi điện tử Mesa Arcade None Baseball Net Lưới bóng chày Red de béisbol Max 60 lbs per bundle; disassemble and bundle Basketball Hoop Đai sắt bóng rổ Aro de baloncesto Drain base and disassemble Bicycle Xe đạp Bicicleta None Cot Cót Catre None Diving Board Ban lặn Trampolín None Exercise Bike xe đạp tập thể dục bicicleta de ejercicio None Fishing Rod Cần câu Caña de pescar Bundle or Boxed; Max 60 lbs per bundle Foosball Table Bảng Foosball Mesa de futbolín None Football Post Bài bóng đá poste de fútbol Max 60 lbs per bundle; disassemble and bundle Golf Club/Golf Bag bộ gậy đánh gôn Club de golf Clubs Bundled separately from bag;60lbs per bundle Hockey Net Mạng khúc côn cầu Red de hockey Max 60 lbs per bundle; disassemble and bundle Hot tub Bồn tắm nước nóng Bañera de hidromasaje Drain and disassemble; 2-3 person size limit Ping Pong Table Bàn chơi bóng bàn Mesa de ping pong None Pogo Stick Gậy Pogo Saltador None Pool Cover Mái che hồ bơi Cubierta de piscina Rolled or folded. Max 60lbs each Pool Filter Bộ lọc hồ bơi Filtro de piscina Bundle; Max 60 lbs per bundle; No Pool Chemicals Accepted Pool Inflatables Pool Inflatables Inflables Piscina Deflate and Bundle; Max 60 lbs per bundle Pool Table bàn bida mesa de billar Removed marble slate, disassemble and bundle legs Punching Bag Túi đấm Saco de boxeo None Skateboard ván trượt Patineta None Skis Ván -

Provider Procedures Manual July 2021 Provider Handbooks

Texas Medicaid Provider Procedures Manual July 2021 Provider Handbooks Durable Medical Equipment, Medical Supplies, and Nutritional Products Handbook The Texas Medicaid & Healthcare Partnership (TMHP) is the claims administrator for Texas Medicaid under contract with the Texas Health and Human Services Commission. TEXAS MEDICAID PROVIDER PROCEDURES MANUAL: VOL. 2 JULY 2021 DURABLE MEDICAL EQUIPMENT, MEDICAL SUPPLIES, AND NUTRITIONAL PRODUCTS Table of Contents 1 General Information . 9 1.1 Payment Window Reimbursement Guidelines for Services Preceding an Inpatient Admission. 9 2 Texas Medicaid (Title XIX) Home Health Services . .10 2.1 Enrollment . .10 2.1.1 Pending Agency Certification . 10 2.1.2 Surety Bond Requirements. 11 2.1.2.1 Proof of Continuation. 11 2.2 Services, Benefits, Limitations and Prior Authorization . .12 2.2.1 Home Health Services . 12 2.2.1.1 Client Eligibility. 12 2.2.1.2 Prior Authorization Requests for Clients with Retroactive Eligibility . 13 2.2.1.3 Prior Authorization . 13 2.2.2 Durable Medical Equipment (DME) and Supplies . 14 2.2.2.1 Modifications, Adjustments, and Repairs . 17 2.2.2.1.1 Accessories . 18 2.2.2.2 Prior Authorization . 18 2.2.3 Home Health DME and Supplies Exceptional Circumstances Provision. 19 2.2.3.1 Prior Authorization Requests for Home Health DME and Supplies under the Exceptional Circumstances Provision. 19 2.2.3.2 Reimbursement and Billing . 20 2.2.4 Medical Supplies . 20 2.2.4.1 Supply Procedure Codes . 22 2.2.4.2 Prior Authorization . 22 2.2.4.3 Cancelling a Prior Authorization. 22 2.2.5 Augmentative Communication Device (ACD) System . -

Access to Medical Care Curriculum

Access to Medical Care Training Tools for Health Care Providers, Disabled Patients and Advocates on Culturally Competent Care and Compliance with Disability Law This training guide accompanies the two DVDs: Access to Medical Care: People with Developmental Disabilities and Access to Medical Care: Adults with Physical Disabilities Access to Medical Care Training Tools for Health Care Providers, Disabled Patients and Advocates on Culturally Competent Care and Compliance with Disability Law Published by WORLD INSTITUTEONDISABILITY 3075 Adeline Street, Suite 280 Berkeley, CA 94703-2545 USA 510-244-6400 www.wid.org Project Director, Marsha Saxton, Ph.D. Collaborating Researcher, Susan Havercamp, Ph.D. Research Associates, Alice Wong, MA., Gabriel Many, MA, Josephine Schallehn Our appreciation is expressed for the generous support of the Nisonger Center, Center for Health Care Strategies, The California HealthCare Foundation, and Kaiser Permanente, which made this program possible. We wish to express our gratitude to our many advisors and participants. The contents of this document express the views of the authors, and the World Institute on Disability, and do not represent the policies of the funders. ISBN Number: 0-942799-08-9 Published 2011 _____________________ The World Institute on Disability (WID) is a nonprofit research and public policy center promoting the civil rights and full societal inclusion of people with disabilities. WID's work focuses on four areas: employment and asset development; accessible health care and personal assistance services; inclusive technology design; and international disability and development. As over half of the Board of Directors and staff are people with disabilities, WID brings a diverse disability perspective to improving public policy and civil rights. -

Download This PDF File

Symposium Contributors INTRODUCTION TO THE SYMPOSIUM Russell Shuttleworth holds a BA and MA in Anthropology from California State University, Sacramento, a Master's Degree in Social Work from San Francisco State University, and a Ph.D. in Medical Anthropology from the University of California, San Francisco-Berkeley. He has worked for many years as a personal assistant for disabled men. For his dissertation, he conducted ethnographic fieldwork in the East San Francisco Bay Area with men with cerebral palsy on their search for sexual intimacy. Dr. Shuttleworth is currently an Ed Robert's Postdoctoral Fellow in Disability Studies at the University of California, Berkeley where he co-teaches the course Anthropology and Disability. He also teaches the innovative course Disability and Sexuality at San Francisco State University. Dr. Shuttleworth has published widely in the areas of disability studies, disability and sexuality studies and the anthropology of disability. Linda Mona is a licensed clinical psychologist who has conducted research and lectured on disability-related topics around the country for the past 13 years. Dr. Mona has worked in a variety of settings conducting both clinical work and research. Most of her clinical and research interests have focused on sexuality and people with disabilities. She obtained her BA in psychology from UCLA and both her masters and doctoral degrees in clinical psychology at Georgia State University. She completed both internship and postdoctoral work at the VA Palo Alto Healthcare System. Dr. Mona has advocated for the inclusion of disability status in university diversity curriculum and has been the energy behind positive changes for university students with disabilities within academic, administrative, and service domains. -

Spinal Cord Injury a Guide Spinal for Cord Living Injury Second Edition

Spinal Cord Injury A Guide SPINAL for CORD Living INJURY SECOND EDITION Sara Palmer, Ph.D. Kay Harris Kriegsman, Ph.D. Jeffrey B. Palmer, M.D. with contributions by John W. McDonald, M.D., Ph.D. and Cristina L. Sadowsky, M.D. the johns hopkins university press A JOHNS HOPKINS PRESS HEALTH BOOK Baltimore A Guide SPINAL for CORD Living INJURY SECOND EDITION Sara Palmer, Ph.D. Kay Harris Kriegsman, Ph.D. Jeffrey B. Palmer, M.D. with contributions by John W. McDonald, M.D., Ph.D. and Cristina L. Sadowsky, M.D. the johns hopkins university press A JOHNS HOPKINS PRESS HEALTH BOOK Baltimore Note to the Reader. This book is not meant to substitute for medical care of people with spinal cord injury, and treatment should not be based solely on its contents. Instead, treatment must be developed in a dialogue between the individual and his or her physician. Our book has been written to help with that dialogue. © 2008 Sara Palmer, Kay Harris Kriegsman, and Jeffrey B. Palmer All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Palmer, Sara. Spinal cord injury : a guide for living / Sara Palmer, Kay Harris Kriegsman, Jeffrey B. Palmer ; with contributions by John W. McDonald and Cristina L. Sadowsky. — 2nd ed. p. ; cm. — (Johns Hopkins Press health book) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Article 9 UNCRPD Accessibility

UK Disability History Month Broadsheet 2020 Text Only version of Broadsheet with description of illustrations in square brackets. [Disability History Month Logo top right of page. A black triangle pointing upwards. A yellow circle in the middle of the triangle says 'disability history month' under the bottom of the triangle are letters 'ACHIEVING EQUALITY' left side 'CELEBRATING OUR LIVES', right side CHALLENGING DISABILISM'.] “We need to make every single thing accessible to every single disabled person.” Stevie Wonder [Graphic: Shows a Zebra crossing leading to pavement and house. The kerb is dropped and textured. The light on crossing has peeps to cross and green light. On the crossing are Stephen Farfler in his hand driven vehicle, a Victorian woman in a Bath Chair and a Asian man in electric chair. On the pavement is a black woman with a white cane. On the road is written 'IT for All' In the building side is a digital information point. At the end of the building are steps. No ramp. The caption reads 'Access: How Far Have we come? How far have we to go? UKDHM 2020. UKDHM.org] In our 11th year we are focusing on Access and asking the questions ‘How far have we come? How far have we to go?’ UK Disability History Month runs from the online launch on the evening of 18th November to 18th December 2020. For disabled people access is now a fundamental human right, as is gaining participation on an equal level with others, regardless of our impairments. Disabled people have struggled for many years to change society’s lived physical and information environment.