NRCS Plants for Pollinator Habitat in Nevada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molecular Identification of Commercialized Medicinal Plants in Southern Morocco

Molecular Identification of Commercialized Medicinal Plants in Southern Morocco Anneleen Kool1*., Hugo J. de Boer1.,A˚ sa Kru¨ ger2, Anders Rydberg1, Abdelaziz Abbad3, Lars Bjo¨ rk1, Gary Martin4 1 Department of Systematic Biology, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2 Department of Botany, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden, 3 Laboratory of Biotechnology, Protection and Valorisation of Plant Resources, Faculty of Science Semlalia, Cadi Ayyad University, Marrakech, Morocco, 4 Global Diversity Foundation, Dar Ylane, Marrakech, Morocco Abstract Background: Medicinal plant trade is important for local livelihoods. However, many medicinal plants are difficult to identify when they are sold as roots, powders or bark. DNA barcoding involves using a short, agreed-upon region of a genome as a unique identifier for species– ideally, as a global standard. Research Question: What is the functionality, efficacy and accuracy of the use of barcoding for identifying root material, using medicinal plant roots sold by herbalists in Marrakech, Morocco, as a test dataset. Methodology: In total, 111 root samples were sequenced for four proposed barcode regions rpoC1, psbA-trnH, matK and ITS. Sequences were searched against a tailored reference database of Moroccan medicinal plants and their closest relatives using BLAST and Blastclust, and through inference of RAxML phylograms of the aligned market and reference samples. Principal Findings: Sequencing success was high for rpoC1, psbA-trnH, and ITS, but low for matK. Searches using rpoC1 alone resulted in a number of ambiguous identifications, indicating insufficient DNA variation for accurate species-level identification. Combining rpoC1, psbA-trnH and ITS allowed the majority of the market samples to be identified to genus level. -

BOTANICAL FIELD RECONNAISSANCE REPORT Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit

BOTANICAL FIELD RECONNAISSANCE REPORT Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit Project: Burke Creek Highway 50 Crossing and Realignment Project FACTS ID: Location: portions of SEC 22 and SEC 23 T13 N R18 E UTM: Survey Dates:5/13/, 6/25, 8/12/2015 Surveyor/s: Jacquelyn Picciani for Wood Rodgers Directions to Site: Access to the west portion of Burke Creek is gained by turning west on Kahle Drive, and parking in the defined parking lot. Access to the east portion of Burke Creek is gained by turning east on Kahle Drive and parking to the north in the adjacent commercial development parking area. USGS Quad Name: South Lake Tahoe Survey type: General and Intuitive Controlled Describe survey route taken: Survey area includes all road shoulders and right –of –way within the proposed project boundaries, a commercial development on east side of US Highway 50 just north of Kahle Drive, and portions of the Burke Creek/Rabe Meadows complex (Figure 1). Project description: The project area includes open space administered by Nevada Tahoe Conservation District and the USFS, and commercial development, with the majority of the project area sloping west to Lake Tahoe. The Nevada Tahoe Conservation District is partnering with USFS, Nevada Department of Transportation (NDOT), Douglas County and the Nevada Division of State Lands to implement the Burke Creek Highway 50 Crossing and Realignment Project (Project). The project area spans from Jennings Pond in Rabe Meadow to the eastern boundary of the Sierra Colina Development in Lake Village. Burke Creek flows through five property ownerships in the project area including the USFS, private (Sierra Colina and 801 Apartments LLC), Douglas County and NDOT. -

KALMIOPSIS Journal of the Native Plant Society of Oregon

KALMIOPSIS Journal of the Native Plant Society of Oregon Kalmiopsis leachiana ISSN 1055-419X Volume 20, 2013 &ôùĄÿĂùñü KALMIOPSIS (irteen years, fourteen issues; that is the measure of how long Journal of the Native Plant Society of Oregon, ©2013 I’ve been editing Kalmiopsis. (is is longer than I’ve lived in any given house or worked for any employer. I attribute this longevity to the lack of deadlines and time clocks and the almost total freedom to create a journal that is a showcase for our state and society. (ose fourteen issues contained 60 articles, 50 book reviews, and 25 tributes to Fellows, for a total of 536 pages. I estimate about 350,000 words, an accumulation that records the stories of Oregon’s botanists, native )ora, and plant communities. No one knows how many hours, but who counts the hours for time spent doing what one enjoys? All in all, this editing gig has been quite an education for me. I can’t think of a more e*ective and enjoyable way to make new friends and learn about Oregon plants and related natural history than to edit the journal of the Native Plant Society of Oregon. Now it is time for me to move on, but +rst I o*er thanks to those before me who started the journal and those who worked with me: the FEJUPSJBMCPBSENFNCFST UIFBVUIPSTXIPTIBSFEUIFJSFYQFSUJTF UIFSFWJFXFST BOEUIF4UBUF#PBSETXIPTVQQPSUFENZXPSL* especially thank those who will follow me to keep this journal &ôùĄÿĂ$JOEZ3PDIÏ 1I% in print, to whom I also o*er my +les of pending manuscripts, UIFTFSWJDFTPGBOFYQFSJFODFEQBHFTFUUFS BSFMJBCMFQSJOUFSBOE &ôùĄÿĂùñü#ÿñĂô mailing service, and the opportunity of a lifetime: editing our +ne journal, Kalmiopsis. -

Northern Pygmy Owl (Glaucidium Gnoma) Pacific

Davis Creek Park BioBlitz Diversity List: (Last Updated 6/23/18) Birds: Northern Pygmy Owl (Glaucidium gnoma) Golden-crowned Kinglet (Regulus satrapa) Pacific Wren (Troglodytes pacificus) Yellow-rumped Warbler (Setophaga coronata) Calliope Hummingbird (Selasphorus calliope) Hairy Woodpecker (Leuconotopicus villosus) Bewick’s Wren (Thryomanes bewickii) Ruby-crowned Kinglet (Regulus calendula) Northern Flicker (Colaptes auratus) Stellar’s Jay (Cyanocitta stelleri) Red-breasted Nuthatch (Sitta canadensis) American Kestrel (Falco sparverius) Spotted Towhee (Pipilo maculatus) Bushtit (Psaltriparus minimus) White-headed Woodpecker Dark-eyed Junco, Oregon (Junco hyemalis) (Picoides albolarvatus) Eurasian Collared Dove Brown Creeper (Certhia americana) (Streptopelia decaocto) California Scrub Jay (Aphelocoma californica) Pygmy Nuthatch (Sitta pygmaea) Double-crested Cormorant Western Bluebird (Sialia mexicana) (Phalacrocorax auritus) Downy Woodpecker (Dryobates pubescens) Mountain Chickadee (Poecile gambeli) Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) Townsend’s Solitaire (Myadestes townsendi) White-crowned Sparrow Clark’s Nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana) (Zonotrichia leucophrys) Golden-crowned Sparrow Blue-gray Gnatcatcher (Polioptila caerulea) (Zonotrichia atricapilla) American Robin (Turdus migratorius) White-breasted Nuthatch (Sitta carolinensis) Mallard Duck (Anas platyrhynchos) American Coot (Fulica americana) Common Merganser (Mergus merganser) Lazuli Bunting (Passerina amoena) European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) Western Tanager (Piranga ludoviciana) -

Terrestrial Ecological Classifications

INTERNATIONAL ECOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION STANDARD: TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATIONS Alliances and Groups of the Central Basin and Range Ecoregion Appendix Accompanying Report and Field Keys for the Central Basin and Range Ecoregion: NatureServe_2017_NVC Field Keys and Report_Nov_2017_CBR.pdf 1 December 2017 by NatureServe 600 North Fairfax Drive, 7th Floor Arlington, VA 22203 1680 38th St., Suite 120 Boulder, CO 80301 This subset of the International Ecological Classification Standard covers vegetation alliances and groups of the Central Basin and Range Ecoregion. This classification has been developed in consultation with many individuals and agencies and incorporates information from a variety of publications and other classifications. Comments and suggestions regarding the contents of this subset should be directed to Mary J. Russo, Central Ecology Data Manager, NC <[email protected]> and Marion Reid, Senior Regional Ecologist, Boulder, CO <[email protected]>. Copyright © 2017 NatureServe, 4600 North Fairfax Drive, 7th floor Arlington, VA 22203, U.S.A. All Rights Reserved. Citations: The following citation should be used in any published materials which reference ecological system and/or International Vegetation Classification (IVC hierarchy) and association data: NatureServe. 2017. International Ecological Classification Standard: Terrestrial Ecological Classifications. NatureServe Central Databases. Arlington, VA. U.S.A. Data current as of 1 December 2017. Restrictions on Use: Permission to use, copy and distribute these data is hereby granted under the following conditions: 1. The above copyright notice must appear in all documents and reports; 2. Any use must be for informational purposes only and in no instance for commercial purposes; 3. Some data may be altered in format for analytical purposes, however the data should still be referenced using the citation above. -

Konzept Für Lokalfauna

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Mitteilungen der Entomologischen Arbeitsgemeinschaft Salzkammergut Jahr/Year: 2004 Band/Volume: 2004 Autor(en)/Author(s): Kallies Axel, Pühringer Franz Artikel/Article: Provisional checklist of the Sesiidae of the world (Lepidoptera: Ditrysia) 1-85 ©Salzkammergut Entomologenrunde; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mitt.Ent.Arb.gem.Salzkammergut 4 1-85 4.12.2004 Provisional checklist of the Sesiidae of the world (Lepidoptera: Ditrysia) Franz PÜHRINGER & Axel KALLIES Abstract: A checklist of Sesiidae of the world provides 2453 names, 1562 of which are currently considered valid taxa (1 family, 2 subfamilies, 10 tribes, 149 genera, 1352 species, and 48 subspecies). Data concerning distribution, type species or type genus, designation, incorrect spelling and emendation, preoccupation and replacement names, synonyms and homonyms, nomina nuda, and rejected names are given. Several new combinations and synonyms are provided. Key words: Sesioidea, systematics, taxonomy, zoogeographic regions. Introduction: Almost 25 years have passed since HEPPNER & DUCKWORTH (1981) published their 'Classification of the Superfamily Sesioidea'. In the meantime great progress has been made in the investigation and classification of the family Sesiidae (clearwing moths). Important monographs covering the Palearctic and Nearctic regions, and partly South America or South-East Asia have been made available (EICHLIN & DUCKWORTH 1988, EICHLIN 1986, 1989, 1995b and 1998, ŠPATENKA et al. 1999, KALLIES & ARITA 2004), and numerous descriptions of new taxa as well as revisions of genera and species described by earlier authors have been published, mainly dealing with the Oriental region (ARITA & GORBUNOV 1995c, ARITA & GORBUNOV 1996b etc.). -

Wildflowers Near Boise Cascade (Wenas) Campground (In the Upper

Wildflowers Near Boise Cascade (Wenas) Campground (in the upper Wenas Valley) Boise Cascade Lands Yakima County, WA from a trip held May 24, 2019 T16N R16E S3; T17N R16E S34, S35 Updated: December 13, 2019 Common Name Scientific Name Family Ferns and Horsetails ____ Fragile Fern Cystopteris fragilis Cystopteridaceae Monocots - Sedges, Rushes, Grasses & Herbaceous Wildflowers ____ Tapertip Onion Allium accuminatum Amaryllidaceae ____ Common Camas Camassia quamash (ssp. maxima ?) Asparagaceae ____ Douglas' Brodiaea Triteleia grandiflora v. grandiflora Asparagaceae ____ Elk Sedge Carex geyeri Cyperaceae ____ Grass Widows Olsynium douglasii v. douglasii Iridaceae ____ Sagebrush Mariposa Calochortus macrocarpus ssp. macrocarpus Liliaceae ____ Yellow Bells Fritillaria pudica Liliaceae ____ Panicled Deathcamas Toxicoscordion paniculatum Melanthiaceae ____ Meadow Deathcamas Toxicosordion venenosum Melanthiaceae ____ Common Western Needlegrass Achnatherum (occidentale ssp. pubescens ?) Poaceae ____ Field Meadow Foxtail Alopecurus pratensis Poaceae ____ Smooth Brome Bromus inermis Poaceae ____ Cheatgrass Bromus tectorum Poaceae ____ Onepike Oatgrass Danthonia unispicata Poaceae ____ Bottlebrush Squirreltail Elymus elymoides Poaceae ____ Bulbous Bluegrass Poa bulbosa Poaceae ____ Bluebunch Wheatgrass Pseudoroegenaria spicata v. spicata Poaceae Trees and Shrubs ____ Blue Elderberry Sambucus cerulea Adoxaceae ____ Stiff Sagebrush Artemisia rigida Asteraceae ____ Gray Rabbitbrush Ericameria nauseosa v. speciosa Asteraceae ____ Shining Oregon Grape Berberis aquifolium Berberidaceae ____ Mountain Alder Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia Betulaceae ____ Common Snowberry Symphoricarpos albus v. laevigatus Caprifoliaceae ____ Kinnikinnik Arctostaphylos nevadensis ssp. nevadensis Ericaceae ____ Wax Currant Ribes cereum v. cereum Grossulariaceae ____ Fir Abies amabilis or A. grandis Pinaceae ____ Ponderosa Pine Pinus ponderosa v. ponderosa Pinaceae ____ Douglas Fir Pseudotsuga menziesii v. menziesii Pinaceae ____ Snowbrush Ceanothus velutinus v. -

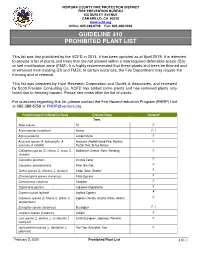

Guideline 410 Prohibited Plant List

VENTURA COUNTY FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICT FIRE PREVENTION BUREAU 165 DURLEY AVENUE CAMARILLO, CA 93010 www.vcfd.org Office: 805-389-9738 Fax: 805-388-4356 GUIDELINE 410 PROHIBITED PLANT LIST This list was first published by the VCFD in 2014. It has been updated as of April 2019. It is intended to provide a list of plants and trees that are not allowed within a new required defensible space (DS) or fuel modification zone (FMZ). It is highly recommended that these plants and trees be thinned and or removed from existing DS and FMZs. In certain instances, the Fire Department may require the thinning and or removal. This list was prepared by Hunt Research Corporation and Dudek & Associates, and reviewed by Scott Franklin Consulting Co, VCFD has added some plants and has removed plants only listed due to freezing hazard. Please see notes after the list of plants. For questions regarding this list, please contact the Fire Hazard reduction Program (FHRP) Unit at 085-389-9759 or [email protected] Prohibited plant list:Botanical Name Common Name Comment* Trees Abies species Fir F Acacia species (numerous) Acacia F, I Agonis juniperina Juniper Myrtle F Araucaria species (A. heterophylla, A. Araucaria (Norfolk Island Pine, Monkey F araucana, A. bidwillii) Puzzle Tree, Bunya Bunya) Callistemon species (C. citrinus, C. rosea, C. Bottlebrush (Lemon, Rose, Weeping) F viminalis) Calocedrus decurrens Incense Cedar F Casuarina cunninghamiana River She-Oak F Cedrus species (C. atlantica, C. deodara) Cedar (Atlas, Deodar) F Chamaecyparis species (numerous) False Cypress F Cinnamomum camphora Camphor F Cryptomeria japonica Japanese Cryptomeria F Cupressocyparis leylandii Leyland Cypress F Cupressus species (C. -

Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 9-17-2018 Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park" (2018). Botanical Studies. 85. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/85 This Flora of Northwest California-Checklists of Local Sites is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF THE REDWOOD NATIONAL & STATE PARKS James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State Univerity Arcata, California 14 September 2018 The Redwood National and State Parks are located in Del Norte and Humboldt counties in coastal northwestern California. The national park was F E R N S established in 1968. In 1994, a cooperative agreement with the California Department of Parks and Recreation added Del Norte Coast, Prairie Creek, Athyriaceae – Lady Fern Family and Jedediah Smith Redwoods state parks to form a single administrative Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosporum • northwestern lady fern unit. Together they comprise about 133,000 acres (540 km2), including 37 miles of coast line. Almost half of the remaining old growth redwood forests Blechnaceae – Deer Fern Family are protected in these four parks. -

2021 Award Recipients

2021 Charles Redd Center Award Recipients Notification and instruction emails will be sent out to all applicants with specifics Annaley Naegle Redd Assistantship Phil S. Allen, Plant and Wildlife Sciences, Brigham Young University, “Sub-alpine Wildflower Meadows as a Template for Water-Conserving Landscape Design” Richard A. Gill, Biology, Brigham Young University, “Biocrust Controls over Regional Carbon Cycling on the Colorado Plateau” Randy Larsen, Plant and Wildlife Sciences, Brigham Young University, “Mountain Lions (Puma concolor), Human Recreation, and the Wildland-Urban Interface: Improving Conservation of an Iconic Species Native to the West” Riley Nelson, Biology, Brigham Young University, “The Bee-Killers: Taxonomy and Phylogenetics of the Robber Fly Genus Proctacanthus (Insecta: Diptera: Asilidae) with Special Reference to Those of Western North America” Sam St. Clair, Plant and Wildlife Sciences, Brigham Young University, “Wildfire and Drought Impacts on Plant Invasions in the Western United States” Annaley Naegle Redd Student Award in Women’s History Amy Griffin, Interdisciplinary (Communications), Brigham Young University, “The Impact of Female Role Models in Television Media on the Perceived Electability of Women” Emily Larsen, History, University of Utah, “Artistic Frontiers: Women and the Making of the Utah Art Scene, 1880– 1950” Charles Redd Fellowship Award in Western American History David R M Beck, Native American Studies, University of Montana, “‘Bribed with Our Own Money,’ Federal Misuse of Tribal Funds in the Termination -

Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plant List

UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plants Below is the most recently updated plant list for UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve. * non-native taxon ? presence in question Listed Species Information: CNPS Listed - as designated by the California Rare Plant Ranks (formerly known as CNPS Lists). More information at http://www.cnps.org/cnps/rareplants/ranking.php Cal IPC Listed - an inventory that categorizes exotic and invasive plants as High, Moderate, or Limited, reflecting the level of each species' negative ecological impact in California. More information at http://www.cal-ipc.org More information about Federal and State threatened and endangered species listings can be found at https://www.fws.gov/endangered/ (US) and http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/ t_e_spp/ (CA). FAMILY NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME LISTED Ferns AZOLLACEAE - Mosquito Fern American water fern, mosquito fern, Family Azolla filiculoides ? Mosquito fern, Pacific mosquitofern DENNSTAEDTIACEAE - Bracken Hairy brackenfern, Western bracken Family Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens fern DRYOPTERIDACEAE - Shield or California wood fern, Coastal wood wood fern family Dryopteris arguta fern, Shield fern Common horsetail rush, Common horsetail, field horsetail, Field EQUISETACEAE - Horsetail Family Equisetum arvense horsetail Equisetum telmateia ssp. braunii Giant horse tail, Giant horsetail Pentagramma triangularis ssp. PTERIDACEAE - Brake Family triangularis Gold back fern Gymnosperms CUPRESSACEAE - Cypress Family Hesperocyparis macrocarpa Monterey cypress CNPS - 1B.2, Cal IPC -

Heterotheca Grandiflora

Invasive KISC Feasibility Combined Kauai Status HPWRA Impacts Status Score Score Score Heterotheca EARLY HIGH RISK Naturalized grandiflora DETECTION (14) 6.5 7.5 14 (telegraph weed) Initial Prioritization Assessment Report completed: December 2017 Report updated as of: N/A Current Recommendation for KISC: Pending Ranking and Committee approval Knowledge Gaps and Contingencies: 1) Delimiting surveys near the known location are necessary to ensure it hasn’t spread beyond its known distribution 2) Discussions with the landowner about seed mix and control around agricultural areas and watercourses are needed. 3) The control crew likely needs to be trained to identify this weed. Background Heterotheca grandiflora (Asteraceae) or “telegraph weed” is a large herb sometimes growing over 1m tall that has been accidentally introduced by way of its sticky seeds throughout Hawaii, mainland USA and Australia (Wagner et al. 1999, HPWRA 2015). H. grandiflora has not been considered for control by KISC; the purpose of this prioritization assessment report is to evaluate whether KISC should attempt eradication (i.e. accept “Target” status) or joint control with partnering agencies (i.e. accept as “Partnership” species status). This will be informed by scoring and comparing H. grandiflora to other “Early Detection” species known to Kauai (See Table 5 in KISC Plant Early Detection Report for status terminology). Detection and Distribution Statewide, H. grandiflora is considered naturalized on all of the main Hawaiian islands (Wagner et al. 1999, Imada 2012). However, only one herbarium voucher collected in 1971 (Hobdy 261, BISH) designates its presence on Kauai. An apparently small population near Mana was detected during the 2014 Statewide Noxious Invasive Pest Program (SNIPP) Surveys, and again during 2015-2017 Surveys (Figure C24- 1).