Tuckerman's Ravine Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

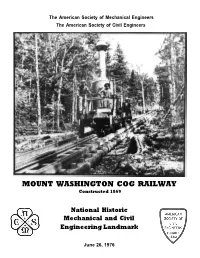

MOUNT WASHINGTON COG RAILWAY Constructed 1869

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers The American Society of Civil Engineers MOUNT WASHINGTON COG RAILWAY Constructed 1869 National Historic Mechanical and Civil Engineering Landmark June 26, 1976 MOUNT WASHINGTON COG RAILWAY Mount Washington, rising 6288 feet above sea level in the mountainous north country of New Hampshire, is the highest peak in the Northeast. The world's first cog railway ascends a western spur of the mountain between Burt and Ammonoosuc Ravines from the Marshfield Base Station which is almost 3600 feet below the summit. The railway is a tribute to the ingenuity and perseverance of its founder, a civil-mechanical engineer, Sylvester Marsh. History attributes the conception and the execution of the railway idea directly to Mr. Marsh. Indeed, his very actions personify the exacting requirements of the National Historic Engineering Landmark programs of The American Society of Civil Engineers and The American Society of Mechanical Engi- neers. The qualities of the Cog Railway are so impressive that, for the first time, two national engineering societies have combined their conclusions in order to designate the train system as a National Historic Mechanical and Civil Engineering Landmark. Sylvester Marsh was born in Campton, New Hampshire on September 30, 1803. When he was nineteen he walked the 150 miles to Boston in three days to seek a job. There he worked on a farm, returned home for a short time, and then again went to Boston where he entered the provision business. After seven years, he moved to Chicago, then a young town of about 300 settlers. From Chicago, Marsh shipped beef and pork to Boston as he developed into a founder of the meat packing industry in the midwestern city. -

Ownership History of the Mount Washington Summit1

STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE Inter-Department Communication DATE: July 23, 2018 FROM: K. Allen Brooks AT (OFFICE) Department of Justice Senior Assistant Attorney General Environmental Protection Bureau SUBJECT: Ownership of Mount Washington Summit TO: The Mount Washington Commission ____________________________________ Ownership History of the Mount Washington Summit1 The ownership history of the summit of Mount Washington is interwoven with that of Sargent’s Purchase, Thompson and Meserve’s Purchase, and numerous other early grants and conveyances in what is now Coos County. Throughout these areas, there has never been a shortage of controversy. Confusion over what is now called Sargent’s Purchase began as far back as 1786 when the Legislature appointed McMillan Bucknam to sell certain state lands. Bucknam conveyed land described as being southwest of Roger’s Location, Treadwell’s Location, and Wentworth’s 1 The following history draws extensively from several N.H. Supreme Court opinions (formerly called the Superior Court of Judicature of New Hampshire) and to a lesser extent from various deeds and third-party information, specifically – Wells v. Jackson Iron Mfg. Co., 44 N.H. 61 (1862); Wells v. Jackson Iron Mfg. Co., 47 N.H. 235 (1866); Wells v. Jackson Iron Mfg. Co., 48 N.H. 491 (1869); Wells v. Jackson Iron Co., 50 N.H. 85 (1870); Coos County Registry of Deeds – (“Book/Page”) B8/117; B9/241; B9/245; B9/246; B9/247; B9/249; B9/249; 12/170; 12/172; B15/122; B15/326; 22/28; B22/28; B22/29; 22/68; B25/255; B28/176; B28/334; B30/285; B30/287; -

VIA EMAIL Pamela G. Monroe, Administrator New Hampshire Site Evaluation Committee 21 South Fruit Street, Suite Concord, NH 03301-2429

............................................................................................................. VIA EMAIL Pamela G. Monroe, Administrator New Hampshire Site Evaluation Committee 21 South Fruit Street, Suite Concord, NH 03301-2429 January 25, 20016 Re: Joint Application of Northern Pass Transmission, LLC and Public Service Company of New Hampshire d/b/a/ Eversource Energy for a Certificate of Site and Facility (SEC Docket No. 2015-6) – Intervention of the Appalachian Mountain Club Dear Ms. Monroe : Enclosed is the intervention filing for the Appalachian Mountain Club relative to the “Joint Application of Northern Pass Transmission, LLC and Public Service Company of New Hampshire d/b/a/ Eversource Energy for a Certificate of Site and Facility ” before the Site Evaluation Committee (SEC Docket No. 2015-6)”. Copies of this letter and enclosure have of this date been forwarded via email to all parties on the email distribution list. We hereby also request that the following individuals be added to the interested party distribution list on behalf of the Appalachian Mountain Club: (i) Dr. Kenneth Kimball, Director of Research, Appalachian Mountain Club, PO Box 298, Gorham, NH 03581, 603-466-8149, [email protected] , (ii) Aladdine Joroff, Staff Attorney, Emmett Environmental Law & Policy Clinic, Harvard Law School, 6 Everett Street, Suite 4119, Cambridge, MA 02138 617- 495-5014 [email protected] (iii) Wendy B. Jacobs, Clinical Professor and Director of the Emmett Environmental Law and Policy Clinic, Harvard Law School, 6 Everett Street, Suite 4119, Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] Main Headquarters : 5 Joy Street • Boston, MA 02108-1490 • 617-523-0636 • outdoors.org Regional Headquarters : Pinkham Notch Visitor Center • 361 Route 16 • Gorham, NH 03581-0298 • 603 466-2721 Additional Offices : Bretton Woods, NH • Greenville, ME • Portland, ME • New York, NY • Bethlehem, PA ............................................................................................................ -

Mountains of Maine Title

e Mountains of Maine: Skiing in the Pine Tree State Dedicated to the Memory of John Christie A great skier and friend of the Ski Museum of Maine e New England Ski Museum extends sincere thanks An Exhibit by the to these people and organizations who contributed New England Ski Museum time, knowledge and expertise to this exhibition. and the e Membership of New England Ski Museum Glenn Parkinson Ski Museum of Maine Art Tighe of Foto Factory Jim uimby Scott Andrews Ted Sutton E. John B. Allen Ken Williams Traveling exhibit made possible by Leigh Breidenbach Appalachian Mountain Club Dan Cassidy Camden Public Library P.W. Sprague Memorial Foundation John Christie Maine Historical Society Joe Cushing Saddleback Mountain Cate & Richard Gilbane Dave Irons Ski Museum of Maine Bruce Miles Sugarloaf Mountain Ski Club Roland O’Neal Sunday River Isolated Outposts of Maine Skiing 1870 to 1930 In the annals of New England skiing, the state of Maine was both a leader and a laggard. e rst historical reference to the use of skis in the region dates back to 1871 in New Sweden, where a colony of Swedish immigrants was induced to settle in the untamed reaches of northern Aroostook County. e rst booklet to oer instruction in skiing to appear in the United States was printed in 1905 by the eo A. Johnsen Company of Portland. Despite these early glimmers of skiing awareness, when the sport began its ascendancy to popularity in the 1930s, the state’s likeliest venues were more distant, and public land ownership less widespread, than was the case in the neighboring states of New Hampshire and Vermont, and ski area development in those states was consequently greater. -

Opuscula Philolichenum, 8: 1-7. 2010

Opuscula Philolichenum, 8: 1-7. 2010. A brief lichen foray in the Mount Washington alpine zone – including Claurouxia chalybeioides, Porina norrlinii and Stereocaulon leucophaeopsis new to North America 1 ALAN M. FRYDAY ABSTRACT. – A preliminary investigation of the lichen biota of Mt. Washington (New Hampshire) is presented based on two days spent on the mountain in August 2008. Claurouxia chalybeioides, Porina norrlinii and Stereocaulon leucophaeopsis are reported for the first time from North America and Frutidella caesioatra is reported for the first time from the United States. A full list of the species recorded during the visit is also presented. INTRODUCTION Mt. Washington, at 1918 m, is the highest peak in northeast North America and has the most alpine tundra of any site in the eastern United States. In spite of this, its lichen biota is very poorly documented with the only published accounts to specifically mention Mt. Washington or the White Mountains by name obtained from the Recent Literature on Lichens web-site (Culberson et al. 2009), which includes all lichenological references since 1536, being an early work by Farlow (1884), and the ecological work by Bliss (1963, 1966), which included a few macrolichens. However, the mountain was a favorite destination of Edward Tuckerman and many records can be extracted from his published taxonomic works (e.g., Tuckerman 1845, 1847, 1882, 1888). More recently Richard Harris and William Buck of the New York Botanical Garden, and Clifford Wetmore of the University of Minnesota have collected lichens on the mountain. Their records have not been published, although the report Wetmore produced for the U.S. -

New Hampshirestate Parks M New Hampshire State Parks M

New Hampshire State Parks Map Parks State State Parks State Magic of NH Experience theExperience nhstateparks.org nhstateparks.org Experience theExperience Magic of NH State Parks State State Parks Map Parks State New Hampshire nhstateparks.org A Mountain Great North Woods Region 19. Franconia Notch State Park 35. Governor Wentworth 50. Hannah Duston Memorial of 9 Franconia Notch Parkway, Franconia Historic Site Historic Site 1. Androscoggin Wayside Possibilities 823-8800 Rich in history and natural wonders; 56 Wentworth Farm Rd, Wolfeboro 271-3556 298 US Route 4 West, Boscawen 271-3556 The timeless and dramatic beauty of the 1607 Berlin Rd, Errol 538-6707 home of Cannon Mountain Aerial Tramway, Explore a pre-Revolutionary Northern Memorial commemorating the escape of Presidential Range and the Northeast’s highest Relax and picnic along the Androscoggin River Flume Gorge, and Old Man of the Mountain plantation. Hannah Duston, captured in 1697 during peak is yours to enjoy! Drive your own car or take a within Thirteen Mile Woods. Profile Plaza. the French & Indian War. comfortable, two-hour guided tour on the 36. Madison Boulder Natural Area , which includes an hour Mt. Washington Auto Road 2. Beaver Brook Falls Wayside 20. Lake Tarleton State Park 473 Boulder Rd, Madison 227-8745 51. Northwood Meadows State Park to explore the summit buildings and environment. 432 Route 145, Colebrook 538-6707 949 Route 25C, Piermont 227-8745 One of the largest glacial erratics in the world; Best of all, your entertaining guide will share the A hidden scenic gem with a beautiful waterfall Undeveloped park with beautiful views a National Natural Landmark. -

THE BROWN BULLETIN Er Stating Reason, on FORM 3547, Postage for Which Is Guaranteed

U. 3. Postage PAID BERLIN, N. H. Permit No. 227 POSTMASTER: If undeliverable FOR ANY REASON notify send- THE BROWN BULLETIN er stating reason, on FORM 3547, postage for which is guaranteed. Published By And For The Employees Of Brown Company Brown Company, Berlin, N. EL Volume BERLIN, NEW HAMPSHIRE, JULY 11, 1950 Number 12 New Insurance Benefits New Contract Provides Wage Available To Employees On July 1, 1950 the new schedule of insurance rates Increase - Three Weeks Norman McRae's and benefits became effective Death Felt By and the old plan was termin- ated. The Company has ar- Many Friends ranged for this increase in Vacation - More Holidays Norman L. McRae, an em- benefits with the Company Results Fruitful ployee of Brown Company carrying a major share of the nr urii D -l since January of 1925, died added premium and the em- Berlin Mills Railway In Many Ways Wednesday, June 28th, fol- ployee contributing an addi- tional 20 cents per month for A new contract was approv- lowing a long period of fail- Buys Forty New Steel Cars ed at a general meeting of ing health. Mr. McRae was the added insurance. With the increased personal benefits, the Union recently after the born in Chatham, New Bruns- favorable completion of dis- wick in 1884 and moved to rates paid by the employee have changed from 40 cents cussions between Brown Com- Berlin, N. H. at the age of 36 pany and Local Union No. 75 to work for Brown Company. to 60 cents per month and de- ductions are being made as of the International Brother- His first work for the com- usual. -

Regional Issues

Regional Issues Without a doubt, Berlin has the most stunning location of any community its size in New Hampshire, if not in New England and beyond. The Androscoggin River courses through it, plunging dramatically over a series of falls that were the original source of Berlin’s economic pre-eminence. The Northern Presidentials soar above the community. On a clear day, the 6288’ summit of Mount Washington, New England’s tallest peak, is clearly visible from most parts of the city. Since the closing of the paper mill in nearby Groveton in 2005 and the closing of the pulp mill in Berlin in 2006, a number of demographic, economic development, and marketing efforts have been undertaken focused on Coos County. There is a higher level of cooperation across the county now than many people have seen in years. It is critical for the county that this cooperation continues. As the largest community in the county, it is probably most critical for Berlin that this spirit continues, and that the observations, recommendations, and initiatives are followed through on. As studies are completed, as implementation efforts are considered, there is occasionally a tendency to focus on the details, to lose track of the comprehensive and cohesive view that was intended. Because the success of these regional efforts is so important to Berlin, their major conclusions are summarized here, so that there is one location where all of those initiatives may be viewed collectively, so that as it views its own implementation efforts, the City can readily review the accompanying recommendations to see that those items are being worked on as well. -

The Neil and Louise Tillotson Anniversary Publication

A BOLD VISION FOR NEW HAMPSHIRE’S NORTH COUNTRY Celebrating the legacy of Neil and Louise Tillotson Neil and Louise Tillotson made the North Country their home. And their legacy is helping make it a better home for others. n 2016, we celebrate 10 years of The Tillotsons’ gift was among the grantmaking from the Neil and Louise largest charitable gifts in the history of I Tillotson Fund, and we celebrate the the state. The fund is one of the largest legacy of these generous people. permanent rural philanthropies in the Neil Tillotson was the ultimate self- country, and is positioned to support the made man: an entrepreneur who, from region in perpetuity. the humblest beginnings, built numerous Look around, and the Tillotsons’ legacy is companies that employed thousands of visible everywhere — a new pharmacy here, people in the region and far beyond. His a ball field there, thriving arts venues, high- wife, Louise, was a force all her own — she quality early childhood education, jobs at small had worked for the BBC, had once built her businesses, magnificent natural resources own house and her own business. preserved, scholarships for great North They traveled the world, but always Country students. And so much more. — always — came back to the North We invite you to celebrate with us — Country. During their lifetimes, they gave with a series of free events honoring quietly and consistently and generously to the Tillotsons, the great work that their hundreds of community efforts. generosity makes possible, and this When Neil Tillotson died in 2001, he beautiful and rugged place that they left the bulk of his assets for charitable loved best of all. -

Passing Through: the Allure of the White Mountains

Passing Through: The Allure of the White Mountains The White Mountains presented nineteenth- century travelers with an American landscape: tamed and welcoming areas surrounded by raw and often terrifying wilderness. Drawn by the natural beauty of the area as well as geologic, botanical, and cultural curiosities, the wealthy began touring the area, seeking the sublime and inspiring. By the 1830s, many small-town tav- erns and rural farmers began lodging the new travelers as a way to make ends meet. Gradually, profit-minded entrepreneurs opened larger hotels with better facilities. The White Moun- tains became a mecca for the elite. The less well-to-do were able to join the elite after midcentury, thanks to the arrival of the railroad and an increase in the number of more affordable accommodations. The White Moun- tains, close to large East Coast populations, were alluringly beautiful. After the Civil War, a cascade of tourists from the lower-middle class to the upper class began choosing the moun- tains as their destination. A new style of travel developed as the middle-class tourists sought amusement and recreation in a packaged form. This group of travelers was used to working and commuting by the clock. Travel became more time-oriented, space-specific, and democratic. The speed of train travel, the increased numbers of guests, and a widening variety of accommodations opened the White Moun- tains to larger groups of people. As the nation turned its collective eyes west or focused on Passing Through: the benefits of industrialization, the White Mountains provided a nearby and increasingly accessible escape from the multiplying pressures The Allure of the White Mountains of modern life, but with urban comforts and amenities. -

Mount Washington

. 1 . Mount Washington WHEN MONROE COUPER and Erik Lattey left Harvard Cabin in Huntington Ravine, the weather was not bad, considering that they were on Mount Washington. The temperature was in the teens, and the wind gusts ranged from forty to sixty miles an hour on the summit. The weather was forecast to hold, and since they didn’t plan to go to the summit, they weren’t worried. They were going to climb a frozen waterfall known as Pinnacle Gully and be back at the cabin before dark. They decided to travel light and leave their larger overnight packs at the cabin. Climbing magazine had recently published an article about an ascent of Pinnacle Gully, an exciting story of triumph over adversity, which had attracted a lot of climbers to that route. No one knows if Couper and Lattey had read it, but they were enthusiastic novice ice climbers and well may have. The story worried Mountain Rescue Service volunteers who felt that it might encour- age people to push on beyond their abilities. Couper and Lattey thought of Pinnacle as an easy climb, a natural next step after the guided trips and climbs the two had completed during previous seasons. They were wrong. While the two men were hiking up the broad and rugged trail toward Pinnacle, Alain Comeau, a leader with Mountain Rescue Service and a local guide, was taking a group up another trail. He saw fast-moving clouds on the horizon. As he said later, “I’ve been in the worst weather on Mount Washington.” He knew how bad it could be. -

White Mountains of New Hampshire PO Box 10 • Rte. 112 / Kancamagus Highway • North Woodstock, New Hampshire, USA 03262 W

MOUN E T T A I I N H S White Mountains of New Hampshire PO Box 10 • Rte. 112 / Kancamagus Highway • North Woodstock, New Hampshire, USA 03262 W N E E W IR H HAMPS contact: Kate Wetherell, [email protected], or call 603-745-8720 | VisitWhiteMountains.com TAKE A TRAIN RIDE The Conway Scenic and Hobo Railroads offer scenic excursions along the river and through the valley. The Mt. Washington Cog Railway offers locomotive rides to the top of Mt. Washington, New England’s highest peak. At Clark’s Trading Post, ride across the world’s only Howe-Truss railroad covered bridge. DISCOVER NATURE At The Flume Gorge, discover Franconia Notch through a free 20 minute High Definition DVD about the area. Enjoy scenic nature walks, PEI stroll along wooden boardwalks and marvel at glacial gorges and boulder caves at Lost River Gorge and Polar Caves Park. TIA TO CONNECTICUT LAKES TO DIXVILLE NOTCH LANCASTER O BERLIN A SC 3 2 CONNECTICUT RIVER Halifax 135 D 16 SANTA’S VILLAGE WHITEFIELD 116 MOUNT WASHINGTON VA JEFFERSON GORHAM A LITTLETON PRESIDENTIAL RANGE 2 3 2 AINE 18 M 93 NO 115 N BETHLEHEM MT. WASHINGTON 16 eal A 95 302 93 302 TWIN MOUNTAIN AUTO ROAD NEW HAMPSHIRE FRANCONIA MOUNT Montr C 302 WASHINGTON LISBON 117 3 WILDCAT Yarmouth COG RAILWAY MOUNTAIN 10 CANNON MOUNTAIN FRANCONIA RANGE AERIAL TRAMWAY PINKHAM NOTCH BATH FRANCONIA NOTCH APPALACHIAN CRAWFORD NOTCH rtland 116 WHITE MOUNTAIN MOUNTAIN CLUB Po 93 STATE PARK 89 112 KINSMAN NOTCH VERMON NATIONAL FOREST JACKSON THE FLUME GORGE LOST RIVER WHALE'S TALE CRAWFORD NOTCH GORGE and WATER PARK STORY LINCOLN BARTLETT GLEN LAND 93 BOULDER CAVES CLARK’S LOON MOUNTAIN RESORT TRADING POST ALPINE ADVENTURES The White Mountains Trail 302 HOBO RAILROAD ATTITASH 112 25 NORTH A National Scenic Byway MOUNTAIN NORTH W 91 WOODSTOCK RESORT CONWAY o NE PASSACONAWAY T 93 CONWAY CRANMORE 81 anchester MOUNTAIN ront M oston KANCAMAGUS HIGHWAY SCENIC RAILROAD ORK B 118 RESORT To Y 25C WARREN 16 ASS.