“It's Not Just a Diet, It's a Lifestyle”: an Exploratory Study Into Preferences of Vegan Definitions Madelon Northa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Derogatory Discourses of Veganism and the Reproduction of Speciesism in UK 1 National Newspapers Bjos 1348 134..152

The British Journal of Sociology 2011 Volume 62 Issue 1 Vegaphobia: derogatory discourses of veganism and the reproduction of speciesism in UK 1 national newspapers bjos_1348 134..152 Matthew Cole and Karen Morgan Abstract This paper critically examines discourses of veganism in UK national newspapers in 2007. In setting parameters for what can and cannot easily be discussed, domi- nant discourses also help frame understanding. Discourses relating to veganism are therefore presented as contravening commonsense, because they fall outside readily understood meat-eating discourses. Newspapers tend to discredit veganism through ridicule, or as being difficult or impossible to maintain in practice. Vegans are variously stereotyped as ascetics, faddists, sentimentalists, or in some cases, hostile extremists. The overall effect is of a derogatory portrayal of vegans and veganism that we interpret as ‘vegaphobia’. We interpret derogatory discourses of veganism in UK national newspapers as evidence of the cultural reproduction of speciesism, through which veganism is dissociated from its connection with debates concerning nonhuman animals’ rights or liberation. This is problematic in three, interrelated, respects. First, it empirically misrepresents the experience of veganism, and thereby marginalizes vegans. Second, it perpetuates a moral injury to omnivorous readers who are not presented with the opportunity to understand veganism and the challenge to speciesism that it contains. Third, and most seri- ously, it obscures and thereby reproduces -

Vegetarian Starter Guide

do good • fEEL GREAt • LOOK GORGEOUS FREE The VegetarianSTARTER GUIDE YUM! QUICK, EASY, FUN RECIPES +30 MOUTHWATERING MEATLESS MEALS EASy • affordABLE • inspirED FOOD Welcome If you’re reading this, you’ve already taken your first step toward a better you and a better world. Think that sounds huge? It is. Cutting out chicken, fish, eggs and other animal products saves countless animals and is the best way to protect the environment. Plus, you’ll never feel more fit or look more fabulous. From Hollywood A-listers like Kristen Bell and Ellen, to musicians like Ariana Grande and Pink, to the neighbors on your block, plant-based eating is everywhere. Even former president Bill Clinton and rapper Jay-Z are doing it! Millions of people have ditched chicken, fish, eggs and other animal products entirely, and tens of millions more are cutting back. You’re already against cruelty to animals. You already want to eat healthy so you can have more energy, live longer, and lower your risk of chronic disease. Congratulations for shaping up your plate to put your values into action! And here’s the best part: it’s never been easier. With this guide at your fingertips, you’re on your way to a fresher, happier you. And this is just the start. You’ll find more recipes, tips, and personal support online at TheGreenPlate.com. Let’s get started! Your Friends at Mercy For Animals reinvent revitalize rewrite rediscover your routine. With the your body. Healthy, plant- perfection. This isn’t about flavor. Prepare yourself easy tips in this guide, based food can nourish being perfect. -

Food Habits and Nutritional Status of East Indian Hindu

FOOD HABITS AND NUTRITIONAL STATUS OF EAST INDIAN HINDU CHILDREN IN BRITISH COLUMBIA by CLARA MING LEE£1 B.Sc.(Food Science), McGill University, 1975 A THESIS.: SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in the Division of HUMAN NUTRITION SCHOOL OF HOME ECONOMICS We accept this thesis as confirming to the required standard. THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, 1977 fcT) CLARA MING LEE PI, 1978 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of HOME ECONOMICS The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1WS FEB 8, 1978 i ABSTRACT A cross-sectional study was carried out to assess the nutritional stutus of a sample of East Indian children in the Vancouver area. The study sample consisted of 132 children from 3 months to 1$ years of age, whose parents belonged to the congregation of the Vishwa Hindu Parished Temple in Bur- naby, B.C. In the dietary assessment of nutritional status, a 24-hour diet recall and a food habits questionnaire were em• ployed on the 132 children. The Canadian Dietary Standard (revised 1975) and Nutrition Canada categories were used for an evaluation of their dietary intake. -

219 No Animal Food

219 No Animal Food: The Road to Veganism in Britain, 1909-1944 Leah Leneman1 UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH There were individuals in the vegetarian movement in Britain who believed that to refrain from eating flesh, fowl, and fish while continuing to partake of dairy products and eggs was not going far enough. Between 1909 and 1912, The Vegetarian Society's journal published a vigorous correspond- ence on this subject. In 1910, a publisher brought out a cookery book entitled, No Animal Food. After World War I, the debate continued within the Vegetarian Society about the acceptability of animal by-products. It centered on issues of cruelty and health as well as on consistency versus expediency. The Society saw its function as one of persuading as many people as possible to give up slaughterhouse products and also refused journal space to those who abjured dairy products. The year 1944 saw the word "vergan" coined and the breakaway Vegan Society formed. The idea that eating animal flesh is unhealthy and morally wrong has been around for millennia, in many different parts of the world and in many cultures (Williams, 1896). In Britain, a national Vegetarian Society was formed in 1847 to promulgate the ideology of non-meat eating (Twigg, 1982). Vegetarianism, as defined by the Society-then and now-and by British vegetarians in general, permitted the consumption of dairy products and eggs on the grounds that it was not necessary to kill the animal to obtain them. In 1944, a group of Vegetarian Society members coined a new word-vegan-for those who refused to partake of any animal product and broke away to form a separate organization, The Vegan Society. -

An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide

AN AHIMSA CRISIS: YOU DECIDE An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 1 2Prakrit Bharati academy,An Ahimsa Crisis: Jai YouP Decideur Prakrit Bharati Pushpa - 356 AN AHIMSA CRISIS: YOU DECIDE Sulekh C. Jain An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 3 Publisher: * D.R. Mehta Founder & Chief Patron Prakrit Bharati Academy, 13-A, Main Malviya Nagar, Jaipur - 302017 Phone: 0141 - 2524827, 2520230 E-mail : [email protected] * First Edition 2016 * ISBN No. 978-93-81571-62-0 * © Author * Price : 700/- 10 $ * Computerisation: Prakrit Bharati Academy, Jaipur * Printed at: Sankhla Printers Vinayak Shikhar Shivbadi Road, Bikaner 334003 An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 4by Sulekh C. Jain An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide Contents Dedication 11 Publishers Note 12 Preface 14 Acknowledgement 18 About the Author 19 Apologies 22 I am honored 23 Foreword by Glenn D. Paige 24 Foreword by Gary Francione 26 Foreword by Philip Clayton 37 Meanings of Some Hindi & Prakrit Words Used Here 42 Why this book? 45 An overview of ahimsa 54 Jainism: a living tradition 55 The connection between ahimsa and Jainism 58 What differentiates a Jain from a non-Jain? 60 Four stages of karmas 62 History of ahimsa 69 The basis of ahimsa in Jainism 73 The two types of ahimsa 76 The three ways to commit himsa 77 The classifications of himsa 80 The intensity, degrees, and level of inflow of karmas due 82 to himsa The broad landscape of himsa 86 The minimum Jain code of conduct 90 Traits of an ahimsak 90 The net benefits of observing ahimsa 91 Who am I? 91 Jain scriptures on ahimsa 91 Jain prayers and thoughts 93 -

Does a Vegan Diet Contribute to Prevention Or Maintenance of Diseases? Malia K

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Kinesiology and Allied Health Senior Research Department of Kinesiology and Allied Health Projects Fall 11-14-2018 Does a Vegan Diet Contribute to Prevention or Maintenance of Diseases? Malia K. Burkholder Cedarville University, [email protected] Danae A. Fields Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ kinesiology_and_allied_health_senior_projects Part of the Kinesiology Commons, and the Public Health Commons Recommended Citation Burkholder, Malia K. and Fields, Danae A., "Does a Vegan Diet Contribute to Prevention or Maintenance of Diseases?" (2018). Kinesiology and Allied Health Senior Research Projects. 6. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/kinesiology_and_allied_health_senior_projects/6 This Senior Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kinesiology and Allied Health Senior Research Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: THE VEGAN DIET AND DISEASES Does a vegan diet contribute to prevention or maintenance of diseases? Malia Burkholder Danae Fields Cedarville University THE VEGAN DIET AND DISEASES 2 Does a vegan diet contribute to prevention or maintenance of diseases? What is the Vegan Diet? The idea of following a vegan diet for better health has been a debated topic for years. Vegan diets have been rising in popularity the past decade or so. Many movie stars and singers have joined the vegan movement. As a result, more and more research has been conducted on the benefits of a vegan diet. In this article we will look at how a vegan diet may contribute to prevention or maintenance of certain diseases such as cancer, diabetes, weight loss, gastrointestinal issues, and heart disease. -

Legal Research Paper Series

Legal Research Paper Series NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY By Rita K. Lomio and J. Paul Lomio Research Paper No. 6 October 2005 Robert Crown Law Library Crown Quadrangle Stanford, California 94305-8612 NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRPAHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY I. Books II. Reports III. Law Review Articles IV. Newspaper Articles (including legal newspapers) V. Sound Recordings and Films VI. Web Resources I. Books RESEARCH GUIDES AND BIBLIOGRAPHIES Hoffman, Piper, and the Harvard Student Animal Legal Defense Fund The Guide to Animal Law Resources Hollis, New Hampshire: Puritan Press, 1999 Reference KF 3841 G85 “As law students, we have found that although more resources are available and more people are involved that the case just a few years ago, locating the resource or the person we need in a particular situation remains difficult. The Guide to Animal Law Resources represents our attempt to collect in one place some of the resources a legal professional, law professor or law student might want and have a hard time finding.” Guide includes citations to organizations and internships, animal law court cases, a bibliography, law schools where animal law courses are taught, Internet resources, conferences and lawyers devoted to the cause. The International Institute for Animal Law A Bibliography of Animal Law Resources Chicago, Illinois: The International Institute for Animal Law, 2001 KF 3841 A1 B53 Kistler, John M. Animal Rights: A Subject Guide, Bibliography, and Internet Companion Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000 HV 4708 K57 Bibliography divided into six subject areas: Animal Rights: General Works, Animal Natures, Fatal Uses of Animals, Nonfatal Uses of Animals, Animal Populations, and Animal Speculations. -

Critical Perspectives on Veganism

CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES ON VEGANISM Edited by Jodey Castricano and Rasmus R. Simonsen The Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series Series Editors Andrew Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford , United Kingdom Priscilla Cohn Villanova , Pennsylvania, USA Aim of the series In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the ethics of our treatment of animals. Philosophers have led the way, and now a range of other scholars have followed from historians to social scientists. From being a marginal issue, animals have become an emerging issue in ethics and in multidisciplinary inquiry. Th is series will explore the challenges that Animal Ethics poses, both conceptually and practically, to traditional understandings of human-animal relations. Specifi cally, the Series will: • provide a range of key introductory and advanced texts that map out ethical positions on animals • publish pioneering work written by new, as well as accomplished, scholars; • produce texts from a variety of disciplines that are multidisciplinary in character or have multidisciplinary relevance. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14421 Jodey Castricano • Rasmus R. Simonsen Editors Critical Perspectives on Veganism Editors Jodey Castricano Rasmus R. Simonsen Th e University of British Columbia Copenhagen School of Design and Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada Technology Copenhagen, Denmark Th e Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series ISBN 978-3-319-33418-9 ISBN 978-3-319-33419-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-33419-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016950059 © Th e Editor(s) (if applicable) and Th e Author(s) 2016 Th is work is subject to copyright. -

Veganism Through a Racial Lens: Vegans of Color Navigating Mainstream Vegan Networks

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 5-24-2018 Veganism through a Racial Lens: Vegans of Color Navigating Mainstream Vegan Networks Iman Chatila Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Chatila, Iman, "Veganism through a Racial Lens: Vegans of Color Navigating Mainstream Vegan Networks" (2018). University Honors Theses. Paper 562. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.569 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Running head: VEGANISM THROUGH A RACIAL LENS 1 Veganism Through a Racial Lens: Vegans of Color Navigating Mainstream Vegan Networks by Iman Chatila An undergraduate honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Science degree in University Honors and Psychology. Thesis Advisor: Charles Klein, PhD, Department of Anthropology Portland State University 2018 Contact: [email protected] VEGANISM THROUGH A RACIAL LENS 2 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Background 5 Methods 7 Positionality 7 Research Questions 7 Interviews & Analysis 8 Results & Discussion 8 Demographics: Race, Age, Education, & Duration of Veganism 8 Social Norms of Vegan Communities 9 Leadership & Redefining Activism 13 Food -

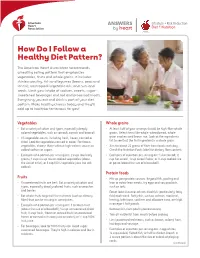

How Do I Follow a Healthy Diet Pattern?

ANSWERS Lifestyle + Risk Reduction by heart Diet + Nutrition How Do I Follow a Healthy Diet Pattern? The American Heart Association recommends a healthy eating pattern that emphasizes vegetables, fruits and whole grains. It includes skinless poultry, fish and legumes (beans, peas and lentils); nontropical vegetable oils; and nuts and seeds. Limit your intake of sodium, sweets, sugar- sweetened beverages and red and processed meats. Everything you eat and drink is part of your diet pattern. Make healthy choices today and they’ll add up to healthier tomorrows for you! Vegetables Whole grains • Eat a variety of colors and types, especially deeply • At least half of your servings should be high-fiber whole colored vegetables, such as spinach, carrots and broccoli. grains. Select items like whole-wheat bread, whole- • All vegetables count, including fresh, frozen, canned or grain crackers and brown rice. Look at the ingredients dried. Look for vegetables canned in water. For frozen list to see that the first ingredient is a whole grain. vegetables, choose those without high-calorie sauces or • Aim for about 25 grams of fiber from foods each day. added sodium or sugars. Check the Nutrition Facts label for dietary fiber content. • Examples of a portion per serving are: 2 cups raw leafy • Examples of a portion per serving are: 1 slice bread; ½ greens; 1 cup cut-up raw or cooked vegetables (about cup hot cereal; 1 cup cereal flakes; or ½ cup cooked rice the size of a fist); or 1 cup 100% vegetable juice (no salt or pasta (about the size of a baseball). -

Speciesism and Language: a Sociolinguistic Approach to the Presence of Speciesism in Current

FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA UNIVERSIDAD DE SALAMANCA FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA GRADO EN ESTUDIOS INGLESES Trabajo de Fin de Grado Speciesism and Language: A sociolinguistic approach to the presence of speciesism in current British speech Salamanca, 2017 Abstract [EN] This paper is an attempt to study the presence of speciesism in the British culture by analyzing its language. Being this form of discrimination still highly prevalent worldwide, the aim of the essay is to analyze to what extent the English language used in Britain is influenced by it. For this purpose, two popular forms of the language have been analyzed: insults and proverbs. The research has been based on the answers of a survey addressed to young British English speakers and the results obtained from oral entries of the British National Corpus. The results of the study have shown a high influence of speciesism in the language and how normalized it is, proving that this form of discrimination is still highly accepted in the British society and therefore present in its language. Keywords: Speciesism, language, discrimination based on species, insults, proverbs. Abstract [ES] El propósito de este trabajo es el de estudiar la presencia del especismo en la cultura británica analizando su lenguaje. Debido al hecho de que esta forma de discriminación está todavía muy extendida alrededor de todo el mundo, este estudio pretende analizar hasta qué punto ha influenciado al inglés hablado en Reino Unido. Para esto hemos analizado dos formas populares del lenguaje: los insultos y los refranes. El estudio se ha basado en las respuestas de una encuesta completada por jóvenes Británicos y en los resultados obtenidos del análisis en entradas orales del British National Corpus. -

Vegan-Friendly Restaurants

WELCOME Hello and thank you for taking a look inside this guide! We, the Animal Advocates of South Central PA, created it for you to use as a compass on your path towards a kinder, healthier life. We are an organization promoting a conscious and compassionate lifestyle which can be summed up in one word: Veganism. It isn’t like other vegan guides, though. It’s tailored for individuals living in South Central Pennsylvania (SCPA) to make your transition as easy as possible. We will lightly touch on the reasons to go vegan (but we highly suggest doing research elsewhere!) and how to make those changes. We will cover everything from where to go out to eat on a Friday night, to what cruelty-free body care brands to check out, and everything in between. We would like to thank you for considering this impactful, wonderful lifestyle, and hope we can assist you on your journey! After exploring this guide, please visit our website, which has many helpful resources, including local restaurant lists, blog articles, and links for further reading. www.animaladvocatesscpa.com Follow us on social media to see what we are up to! “Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better”. -Maya Angelou 2 Vegan Guide for South Central PA WHY GO VEGAN? For The Animals | For The Environment For Our Health | For Everything! There are many reasons people go vegan. In some cases, it’s for the environment. Animal agriculture is a significant ecological problem, contributing more greenhouse gas emissions than the entire transportation sector.