The Introduction of Delftware Tiles to North America and Their Enduring Legacy in Charleston, South Carolina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7 Great Pottery Projects

ceramic artsdaily.org 7 great pottery projects | Second Edition | tips on making complex pottery forms using basic throwing and handbuilding skills This special report is brought to you with the support of Atlantic Pottery Supply Inc. 7 Great Pottery Projects Tips on Making Complex Pottery Forms Using Basic Throwing and Handbuilding Skills There’s nothing more fun than putting your hands in clay, but when you get into the studio do you know what you want to make? With clay, there are so many projects to do, it’s hard to focus on which ones to do first. So, for those who may wany some step-by-step direction, here are 7 great pottery projects you can take on. The projects selected here are easy even though some may look complicated. But with our easy-to-follow format, you’ll be able to duplicate what some of these talented potters have described. These projects can be made with almost any type of ceramic clay and fired at the recommended temperature for that clay. You can also decorate the surfaces of these projects in any style you choose—just be sure to use food-safe glazes for any pots that will be used for food. Need some variation? Just combine different ideas with those of your own and create all- new projects. With the pottery techniques in this book, there are enough possibilities to last a lifetime! The Stilted Bucket Covered Jar Set by Jake Allee by Steve Davis-Rosenbaum As a college ceramics instructor, Jake enjoys a good The next time you make jars, why not make two and time just like anybody else and it shows with this bucket connect them. -

'A Mind to Copy': Inspired by Meissen

‘A Mind to Copy’: Inspired by Meissen Anton Gabszewicz Independent Ceramic Historian, London Figure 1. Sir Charles Hanbury Williams by John Giles Eccardt. 1746 (National Portrait Gallery, London.) 20 he association between Nicholas Sprimont, part owner of the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, Sir Everard Fawkener, private sec- retary to William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, the second son of King George II, and Sir Charles Hanbury Williams, diplomat and Tsometime British Envoy to the Saxon Court at Dresden was one that had far-reaching effects on the development and history of the ceramic industry in England. The well-known and oft cited letter of 9th June 1751 from Han- bury Williams (fig. 1) to his friend Henry Fox at Holland House, Kensington, where his china was stored, sets the scene. Fawkener had asked Hanbury Williams ‘…to send over models for different Pieces from hence, in order to furnish the Undertakers with good designs... But I thought it better and cheaper for the manufacturers to give them leave to take away any of my china from Holland House, and to copy what they like.’ Thus allowing Fawkener ‘… and anybody He brings with him, to see my China & to take away such pieces as they have a mind to Copy.’ The result of this exchange of correspondence and Hanbury Williams’ generous offer led to an almost instant influx of Meissen designs at Chelsea, a tremendous impetus to the nascent porcelain industry that was to influ- ence the course of events across the industry in England. Just in taking a ca- sual look through the products of most English porcelain factories during Figure 2. -

Ihmi^^Rawm^Miw^Ii^^^^^^^ TITLE of SURVEY: "' - I -'• .'' ,! • •'-' •••'•'

I Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE New Hampshire COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Rockingham INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FQR-.NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATei?^!^ hi ( 1976 (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) '. -•----•.--.--- - .---:..:, ..-.._-..-: ,..-.-:. J..-. (iiiiiiiiiii^^ COMMON :^~-^. •...-..... • , j ." '••••• •-••-•• -\ ••'*.•••:. ^ •;. #t The^ Oilman "Garrison" House" ^ - w , -•<. .-v;. \ AND/ OR HISTORIC: ,. .. .:..._.... - -'-. '^\ \ ''- ; f / ."^ /^- , The Oilman "Garrisbn" House, ' ill ^^;:l||fili?f;lli;;|||&:l:p^>^ STREET ANDNUMBER: .. • . 12 Water Sftree"t; : ,.. i: -:--ir' -"••'•'•' L^'l- "'•.'.•'•>' lr-----.I'iv>rV/-Uj./l. CITY OR TOWN: . '.."'""' CON GRESSIONAL DISTRICT: .; ::. ..,.'—*-; Exeter' ; •• " • '- : '^: ;;••'- •'•••'•; ••'•' :^/-'.--;\- -"•-•.- :-i .-i ••.-• .- ?.-M\-.-. "^.'/'i ! •!Q,M,-I » /rr,-/ N'TYf- ' ' y-^V^ ; -'•'-' '!'-.'-"-- (-CODE STATE "• . .;.-;,- ,"• ' .'- .'->,",-.".' • :.CODE. CO-U .New Hampshire .. _; ;, . 33 Rockinffham VV.-r-l. ^-\\ 015 tiiliiAssfFiciA^fQN^^ fiififffffi^ •-.,-• CATEGORY--.; .. : .,., , OWNERSHIP ^ - STATUS ACCESSIBLE •z. .. (Check One) • ; v ": ' - TO THE PUBLIC Q : District '(X' Building • • CD' Public. , Public Acquisition: . JC] Occupied Yes: o n Site - • .Q Structure' ® Private" '-., Q In Process. "; Q ' Unoccupied ".. ' ^' Restricted ,0 Object ,.-,--.":. ' D- Both. , ". D,. Being Considered . \ B Preservailon work Derestricted " ' • ' • .... " " • ' *| —— I Kl ' ••.-'.'• . • '• • -.-'•'.-• -

Fast Fossils Carbon-Film Transfer on Saggar-Fired Porcelain by Dick Lehman

March 2000 1 2 CERAMICS MONTHLY March 2000 Volume 48 Number 3 “Leaves in Love,” 10 inches in height, handbuilt stoneware with abraded glaze, by Michael Sherrill, Hendersonville, North FEATURES Carolina. 34 Fast Fossils 40 Carbon-Film Transfer on Saggar-Fired Porcelain by Dick Lehman 38 Steven Montgomery The wood-firing kiln at Buck Industrial imagery with rich texture and surface detail Pottery, Gruene, Texas. 40 Michael Sherrill 62 Highly refined organic forms in porcelain 42 Rasa and Juozas Saldaitis by Charles Shilas Lithuanian couple emigrate for arts opportunities 45 The Poetry of Punchong Slip-Decorated Ware by Byoung-Ho Yoo, Soo-Jong Ree and Sung-Jae Choi by Meghen Jones 49 No More Gersdey Borateby JejfZamek Why, how and what to do about it 51 Energy and Care Pit Firing Burnished Pots on the Beach by Carol Molly Prier 55 NitsaYaffe Israeli artist explores minimalist abstraction in vessel forms “Teapot,” approximately 9 inches in height, white 56 A Female Perspectiveby Alan Naslund earthenware with under Female form portrayed by Amy Kephart glazes and glazes, by Juozas and Rasa Saldaitis, 58 Endurance of Spirit St. Petersburg, Florida. The Work of Joanne Hayakawa by Mark Messenger 62 Buck Pottery 42 17 Years of Turnin’ and Burnin’ by David Hendley 67 Redware: Tradition and Beyond Contemporary and historical work at the Clay Studio “Bottle,” 7 inches in height, wheel-thrown porcelain, saggar 68 California Contemporary Clay fired with ferns and sumac, by The cover:“Echolalia,” San Francisco invitational exhibition Dick Lehman, Goshen, Indiana. 29½ inches in height, press molded and assembled, 115 Conquering Higher Ground 34 by Steven Montgomery, NCECA 2000 Conference Preview New York City; see page 38. -

H. H. Richardson's House for Reverend Browne, Rediscovered

H. H. Richardson’s House for Reverend Browne, Rediscovered mark wright Wright & Robinson Architects Glen Ridge, New Jersey n 1882 Henry Hobson Richardson completed a mod- flowering, brief maturity, and dissemination as a new Amer- est shingled cottage in the town of Marion, overlook- ican vernacular. To abbreviate Scully’s formulation, the Iing Sippican Harbor on the southern coast of Shingle Style was a fusion of imported strains of the Eng- Massachusetts (Figure 1). Even though he had only seen it lish Queen Anne and Old English movements with a con- in a sadly diminished, altered state and shrouded in vines, in current revival of interest in the seventeenth-century 1936 historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock would neverthe- colonial building tradition in wood shingles, a tradition that less proclaim, on the walls of the Museum of Modern Art survived at that time in humble construction up and down (MoMA) in New York, that the structure was “perhaps the the New England seaboard. The Queen Anne and Old most successful house ever inspired by the Colonial vernac- English were both characterized by picturesque massing, ular.”1 The alterations made shortly after the death of its the elision of the distinction between roof and wall through first owner in 1901 obscured the exceptional qualities that the use of terra-cotta “Kent tile” shingles on both, the lib- marked the house as one of Richardson’s most thoughtful eral use of glass, and dynamic planning that engaged func- works; they also caused it to be misunderstood—in some tionally complex houses with their landscapes. -

E. Heritage Health Index Participants

The Heritage Health Index Report E1 Appendix E—Heritage Health Index Participants* Alabama Morgan County Alabama Archives Air University Library National Voting Rights Museum Alabama Department of Archives and History Natural History Collections, University of South Alabama Supreme Court and State Law Library Alabama Alabama’s Constitution Village North Alabama Railroad Museum Aliceville Museum Inc. Palisades Park American Truck Historical Society Pelham Public Library Archaeological Resource Laboratory, Jacksonville Pond Spring–General Joseph Wheeler House State University Ruffner Mountain Nature Center Archaeology Laboratory, Auburn University Mont- South University Library gomery State Black Archives Research Center and Athens State University Library Museum Autauga-Prattville Public Library Troy State University Library Bay Minette Public Library Birmingham Botanical Society, Inc. Alaska Birmingham Public Library Alaska Division of Archives Bridgeport Public Library Alaska Historical Society Carrollton Public Library Alaska Native Language Center Center for Archaeological Studies, University of Alaska State Council on the Arts South Alabama Alaska State Museums Dauphin Island Sea Lab Estuarium Alutiiq Museum and Archaeological Repository Depot Museum, Inc. Anchorage Museum of History and Art Dismals Canyon Bethel Broadcasting, Inc. Earle A. Rainwater Memorial Library Copper Valley Historical Society Elton B. Stephens Library Elmendorf Air Force Base Museum Fendall Hall Herbarium, U.S. Department of Agriculture For- Freeman Cabin/Blountsville Historical Society est Service, Alaska Region Gaineswood Mansion Herbarium, University of Alaska Fairbanks Hale County Public Library Herbarium, University of Alaska Juneau Herbarium, Troy State University Historical Collections, Alaska State Library Herbarium, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa Hoonah Cultural Center Historical Collections, Lister Hill Library of Katmai National Park and Preserve Health Sciences Kenai Peninsula College Library Huntington Botanical Garden Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park J. -

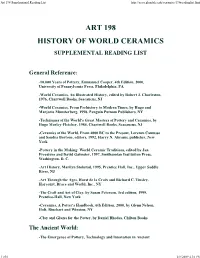

Art 198 Supplemental Reading List

Art 198 Supplemental Reading List http://seco.glendale.edu/ceramics/198readinglist.html ART 198 HISTORY OF WORLD CERAMICS SUPPLEMENTAL READING LIST General Reference: -10,000 Years of Pottery, Emmanuel Cooper, 4th Edition, 2000, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA -World Ceramics, An Illustrated History, edited by Robert J. Charleston, 1976, Chartwell Books, Seacaucus, NJ -World Ceramics, From Prehistory to Modern Times, by Hugo and Marjorie Munsterberg, 1998, Penguin Putnam Publishers, NY -Techniques of the World's Great Masters of Pottery and Ceramics, by Hugo Morley-Fletcher, 1984, Chartwell Books, Seacaucus, NJ -Ceramics of the World, From 4000 BC to the Present, Lorenzo Camusso and Sandra Bortone, editors, 1992, Harry N. Abrams, publisher, New York -Pottery in the Making: World Ceramic Traditions, edited by Jan Freestone and David Gaimster, 1997, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D. C. -Art History, Marilyn Stokstad, 1995, Prentice Hall, Inc., Upper Saddle River, NJ -Art Through the Ages, Horst de la Croix and Richard C. Tinsley, Harcourt, Brace and World, Inc., NY -The Craft and Art of Clay, by Susan Peterson, 3rd edition, 1999, Prentice-Hall, New York -Ceramics, A Potter's Handbook, 6th Edition, 2000, by Glenn Nelson, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, NY -Clay and Glazes for the Potter, by Daniel Rhodes, Chilton Books The Ancient World: -The Emergence of Pottery, Technology and Innovation in Ancient 1 of 6 2/8/2009 4:10 PM Art 198 Supplemental Reading List http://seco.glendale.edu/ceramics/198readinglist.html Societies, by William K.Barnett and John W. Hoopes, 1995, Simthsonian Institution Press, 1995, Washington, DC -Cycladic Art: The N. -

2013 EFP Catalog 19 April

Ephraim Pottery Studio Collection April 2013 Welcome! Dear pottery and tile enthusiasts, As you can see from this catalog, we’ve been busy working on new pottery and tiles over the past several months. While this is an ongo- ing process, we have also been taking a closer look at what we want our pottery to represent. Refocusing on our mission, we have been reminded how important the collaborative work environment is to our studio. When our artists bring their passion for their work to the group and are open to elevating their vision, boundaries seem to drop away. I like to think that our world would be a much better place if a collaborative approach could be emphasized in our homes, schools, and workplaces... in all areas of our lives, in fact. “We are better to- gether” is a motto that is in evidence every day at EFP. Many times in the creative process, we can develop a new concept most of the way quickly. Often, it’s that last 10% that requires work, grit and determination. It can take weeks, months, or even years to bring a new concept to fruition. Such has been the case with frames and stands for our tiles. Until recently, John Raymond was in charge of glaz- ing. As some of you know, John is also a talented woodworker who has been developing a line of quarter-sawn oak frames and stands for our tiles. While we have been able to display some of these at shows and in our galleries over the past year, we would like to make frames and stands available to all our customers. -

Leeds Arts Calendar LEEDS ARTS CALENDAR MICROFILMED Starting with the First Issue Published in 1947, the Entire Leeds Art Calendar Is Now Available on Micro- Film

Leeds Arts Calendar LEEDS ARTS CALENDAR MICROFILMED Starting with the first issue published in 1947, the entire Leeds Art Calendar is now available on micro- film. Write for information or send orders direct to: University Microfilms, Inc., 300N Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106, U.S.A. Leeds Art Collections Fund This is an appeal to all who are interested in the Arts. The Leeds Art Collections Fund is the source of regular funds for buying works of art for the Leeds collection. We want more subscribing members to give one and a half guineas or upwards each year. Why not identify yourself with the Art Gallery and Temple Newsam; receive your Arts Calendar free, receive invitations to all functions, private views and organised visits to places ot Cover Design interest, by writing for an application form to the Detail of a Staffordshire salt-glaze stoneware mug Hon Treasurer, E. M. Arnold Butterley Street, Leeds 10 with "Scratch Blue" decoration of a cattle auction Esq., scene; inscribed "John Cope 1749 Hear goes". From the Hollings Collection, Leeds. LEEDS ARTS CALENDAR No. 67 1970 THE AMENITIES COMMITTEE The Lord Mayor Alderman J. T. V. Watson, t.t..s (Chairman) Alderman T. W. Kirkby Contents Alderman A. S. Pedley, D.p.c. Alderman S. Symmonds Councillor P. N. H. Clokie Councillor R. I. Ellis, A.R.A.M. Councillor H. Farrell Editorial 2 J. Councillor Mrs. E. Haughton Councillor Mrs. Collector's Notebook D. E. Jenkins A Leeds 4 Councillor Mrs. A. Malcolm Councillor Miss C. A. Mathers Some Trifles from Leeds 12 Councillor D. -

CERAMICS MONTHLY a Letter from the Editor

lili.~o;.; ...... "~,~ I~,~.'il;:---.-::::~ ! 1 ~li~'. " " " -"-- :" ' " " ~ ''~: P #~" ...................... ~.c .~ ~7',.~,c-" =---.......... ,.,_,. ~-,~ !,' .......... i."' "~"" ~' ...... !I "'" ~ r~P.tfi.~. ......"-~ .............~:- - -~-~:==-.- .,,,~4~i t,_,i..... ,; ................... ~,~ ,~.i~'~ ..... -. ~,'...;;,. :,,,~.... ..... , , . ,¶~ ~'~ .... ...... i.,>-- ,,~ ........... ., ~ ~...... ~. ~' i .,.... .i .. - i .,.it ....... ~-i ;~ "~" o.., I llili'i~'lii llilillli'l " "" ............... i ill '~l It qL[~ ,, ,q ...... ..... .i~! 'l • IN ~, L'.,.-~':';" ............. ........ 'i'.~'~ ......... ~':',q. ~....~ • ~.,i ................... dl ..... i~,%,...;,, ......................... Ill ltj'llll 1". ........ : ...... " - "- ~1 ~,~.,.--..• ~:I,'.s ...... .................... I' '#~'~ .......................... ~; ~"" .. • .,:,.. _., I;.~P~,,,,...-...,,,.,l.,. ........,..._ .~ -.. ,,~l."'~ ........ ,~ ~,~'~'i '.. .................. ....... -,- l'..~ .......... .,.,.,,........... r4" ...." ' ~'~'"" -'- ~i i~,~'- ~>'- i ill. ....................... ,'., i,'; "" " ........ " • . it, 1 ~,:. i ~1' ~ ~'$~'~-,~,s',il~.;;;:.;' - " ~!'~~!" "4"' '~ "~'" "" I I~i', ~l~ I,J ..v ~,J ,.,, ,., i o. ~.. pj~ ~. ....... yit .~,,. .......... :,~ ,,~ t; .... ~ | I ~li~,. ,~ i'..~.. ~.. .... I TL-8, Ins Economical Chamber TOP-LOADING $14715 high f.o. bus, cra ELECTRIKILNS py .... ter Save your time . cut power costs! These ElectriKilns are de- signed for the special needs of hobbyist and teacher. Fast-firing up to 2300 ° F .... heat-saving . low -

Greek Pottery Gallery Activity

SMART KIDS Greek Pottery The ancient Greeks were Greek pottery comes in many excellent pot-makers. Clay different shapes and sizes. was easy to find, and when This is because the vessels it was fired in a kiln, or hot were used for different oven, it became very strong. purposes; some were used for They decorated pottery with transportation and storage, scenes from stories as well some were for mixing, eating, as everyday life. Historians or drinking. Below are some have been able to learn a of the most common shapes. great deal about what life See if you can find examples was like in ancient Greece by of each of them in the gallery. studying the scenes painted on these vessels. Greek, Attic, in the manner of the Berlin Painter. Panathenaic amphora, ca. 500–490 B.C. Ceramic. Bequest of Mrs. Allan Marquand (y1950-10). Photo: Bruce M. White Amphora Hydria The name of this three-handled The amphora was a large, two- vase comes from the Greek word handled, oval-shaped vase with for water. Hydriai were used for a narrow neck. It was used for drawing water and also as urns storage and transport. to hold the ashes of the dead. Krater Oinochoe The word krater means “mixing The Oinochoe was a small pitcher bowl.” This large, two-handled used for pouring wine from a krater vase with a broad body and wide into a drinking cup. The word mouth was used for mixing wine oinochoe means “wine-pourer.” with water. Kylix Lekythos This narrow-necked vase with The kylix was a drinking cup with one handle usually held olive a broad, relatively shallow body. -

Volume 18 (2011), Article 3

Volume 18 (2011), Article 3 http://chinajapan.org/articles/18/3 Lim, Tai Wei “Re-centering Trade Periphery through Fired Clay: A Historiography of the Global Mapping of Japanese Trade Ceramics in the Premodern Global Trading Space” Sino-Japanese Studies 18 (2011), article 3. Abstract: A center-periphery system is one that is not static, but is constantly changing. It changes by virtue of technological developments, design innovations, shifting centers of economics and trade, developmental trajectories, and the historical sensitivities of cultural areas involved. To provide an empirical case study, this paper examines the material culture of Arita/Imari 有田/伊万里 trade ceramics in an effort to understand the dynamics of Japan’s regional and global position in the transition from periphery to the core of a global trading system. Sino-Japanese Studies http://chinajapan.org/articles/18/3 Re-centering Trade Periphery through Fired Clay: A Historiography of the Global Mapping of Japanese Trade Ceramics in the 1 Premodern Global Trading Space Lim Tai Wei 林大偉 Chinese University of Hong Kong Introduction Premodern global trade was first dominated by overland routes popularly characterized by the Silk Road, and its participants were mainly located in the vast Eurasian space of this global trading area. While there are many definitions of the Eurasian trading space that included the so-called Silk Road, some of the broadest definitions include the furthest ends of the premodern trading world. For example, Konuralp Ercilasun includes Japan in the broadest definition of the silk route at the farthest East Asian end.2 There are also differing interpretations of the term “Silk Road,” but most interpretations include both the overland as well as the maritime silk route.