MODERN ART and IDEAS 4 1914–1928 a Guide for Educators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Etoth Dissertation Corrected.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School The College of Arts and Architecture FROM ACTIVISM TO KIETISM: MODERIST SPACES I HUGARIA ART, 1918-1930 BUDAPEST – VIEA – BERLI A Dissertation in Art History by Edit Tóth © 2010 Edit Tóth Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 The dissertation of Edit Tóth was reviewed and approved* by the following: Nancy Locke Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Head of the Department of Art History Michael Bernhard Associate Professor of Political Science *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT From Activism to Kinetism: Modernist Spaces in Hungarian Art, 1918-1930. Budapest – Vienna – Berlin investigates modernist art created in Central Europe of that period, as it responded to the shock effects of modernity. In this endeavor it takes artists directly or indirectly associated with the MA (“Today,” 1916-1925) Hungarian artistic and literary circle and periodical as paradigmatic of this response. From the loose association of artists and literary men, connected more by their ideas than by a distinct style, I single out works by Lajos Kassák – writer, poet, artist, editor, and the main mover and guiding star of MA , – the painter Sándor Bortnyik, the polymath László Moholy- Nagy, and the designer Marcel Breuer. This exclusive selection is based on a particular agenda. First, it considers how the failure of a revolutionary reorganization of society during the Hungarian Soviet Republic (April 23 – August 1, 1919) at the end of World War I prompted the Hungarian Activists to reassess their lofty political ideals in exile and make compromises if they wanted to remain in the vanguard of modernity. -

El Lissitzky Letters and Photographs, 1911-1941

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf6r29n84d No online items Finding aid for the El Lissitzky letters and photographs, 1911-1941 Finding aid prepared by Carl Wuellner. Finding aid for the El Lissitzky 950076 1 letters and photographs, 1911-1941 ... Descriptive Summary Title: El Lissitzky letters and photographs Date (inclusive): 1911-1941 Number: 950076 Creator/Collector: Lissitzky, El, 1890-1941 Physical Description: 1.0 linear feet(3 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California, 90049-1688 (310) 440-7390 Abstract: The El Lissitzky letters and photographs collection consists of 106 letters sent, most by Lissitzky to his wife, Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, along with his personal notes on art and aesthetics, a few official and personal documents, and approximately 165 documentary photographs and printed reproductions of his art and architectural designs, and in particular, his exhibition designs. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in German Biographical/Historial Note El Lissitzky (1890-1941) began his artistic education in 1909, when he traveled to Germany to study architecture at the Technische Hochschule in Darmstadt. Lissitzky returned to Russia in 1914, continuing his studies in Moscow where he attended the Riga Polytechnical Institute. After the Revolution, Lissitzky became very active in Jewish cultural activities, creating a series of inventive illustrations for books with Jewish themes. These formed some of his earliest experiments in typography, a key area of artistic activity that would occupy him for the remainder of his life. -

Henryk Berlewi

HENRYK BERLEWI HENRYK © 2019 Merrill C. Berman Collection © 2019 AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F T HENRYK © O H C E M N 2019 A E R M R R I E L L B . C BERLEWI (1894-1967) HENRYK BERLEWI (1894-1967) Henryk Berlewi, Self-portrait,1922. Gouache on paper. Henryk Berlewi, Self-portrait, 1946. Pencil on paper. Muzeum Narodowe, Warsaw Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Design and production by Jolie Simpson Edited by Dr. Karen Kettering, Independent Scholar, Seattle, USA Copy edited by Lisa Berman Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2019 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2019 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Élément de la Mécano- Facture, 1923. Gouache on paper, 21 1/2 x 17 3/4” (55 x 45 cm) Acknowledgements: We are grateful to the staf of the Frick Collection Library and of the New York Public Library (Art and Architecture Division) for assisting with research for this publication. We would like to thank Sabina Potaczek-Jasionowicz and Julia Gutsch for assisting in editing the titles in Polish, French, and German languages, as well as Gershom Tzipris for transliteration of titles in Yiddish. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Marek Bartelik, author of Early Polish Modern Art (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005) and Adrian Sudhalter, Research Curator of the Merrill C. -

The Russian Avant-Garde 1912-1930" Has Been Directedby Magdalenadabrowski, Curatorial Assistant in the Departmentof Drawings

Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art leV'' ST,?' T Chairm<ln ,he Boord;Ga,dner Cowles ViceChairman;David Rockefeller,Vice Chairman;Mrs. John D, Rockefeller3rd, President;Mrs. Bliss 'Ce!e,Slder";''i ITTT V P NealJ Farrel1Tfeasure Mrs. DouglasAuchincloss, Edward $''""'S-'ev C Burdl Tn ! u o J M ArmandP Bar,osGordonBunshaft Shi,| C. Burden,William A. M. Burden,Thomas S. Carroll,Frank T. Cary,Ivan Chermayeff, ai WniinT S S '* Gianlui Gabeltl,Paul Gottlieb, George Heard Hdmilton, Wal.aceK. Harrison, Mrs.Walter Hochschild,» Mrs. John R. Jakobson PhilipJohnson mM'S FrankY Larkin,Ronalds. Lauder,John L. Loeb,Ranald H. Macdanald,*Dondd B. Marron,Mrs. G. MaccullochMiller/ J. Irwin Miller/ S.I. Newhouse,Jr., RichardE Oldenburg,John ParkinsonIII, PeterG. Peterson,Gifford Phillips, Nelson A. Rockefeller* Mrs.Albrecht Saalfield, Mrs. Wolfgang Schoenborn/ MartinE. Segal,Mrs Bertram Smith,James Thrall Soby/ Mrs.Alfred R. Stern,Mrs. Donald B. Straus,Walter N um'dWard'9'* WhlTlWheeler/ Johni hTO Hay Whitney*u M M Warbur Mrs CliftonR. Wharton,Jr., Monroe * HonoraryTrustee Ex Officio 0'0'he "ri$°n' Ctty ot^New^or^ °' ' ^ °' "** H< J Goldin Comptrollerat the Copyright© 1978 by TheMuseum of ModernArt All rightsreserved ISBN0-87070-545-8 TheMuseum of ModernArt 11West 53 Street,New York, N.Y 10019 Printedin the UnitedStates of America Foreword Asa resultof the pioneeringinterest of its first Director,Alfred H. Barr,Jr., TheMuseum of ModernArt acquireda substantialand uniquecollection of paintings,sculpture, drawings,and printsthat illustratecrucial points in the Russianartistic evolution during the secondand third decadesof this century.These holdings have been considerably augmentedduring the pastfew years,most recently by TheLauder Foundation's gift of two watercolorsby VladimirTatlin, the only examplesof his work held in a public collectionin the West. -

Staging Revolution: the Constructivist Debate About Composition

Staging Revolution: The Constructivist Debate about Composition Introduction Among the relatively few areas of agreement after the 1917 Russian Revolution, two are particularly noteworthy. The first is the widespread perception that the urban environment was chaotic. Whereas few people agreed as to the source of this chaos (choosing to blame it on the capitalists, the architects, or the intelligentsia), almost everyone believed that urban life after the revolution did not justify the sacrifices and traumas imposed by three years of civil war. The second area of agreement concerned the role of the theater: despite continued and almost irreconcilable differences about what the future should look like, there was almost complete agreement that art and theater could be “weapons” or tools in the revolution. Theater, in particular, would lead the way: from Lenin’s project for monumental propaganda (1918) to the Russian futurists’ declaration that the “streets should be a holiday of art for the people,” there was widespread agreement that art should be taken to the streets, that it was capable of communicating messages in a voice which would be understood, and that theatricality was the key to the unification of the arts. Ironically, one of the reasons why constructivism has been so difficult to study is the fact that it was long understood as a form of art which was against the creation of art. But one of the core values of constructivism was not the rejection of art but the belief that the only type of art which has meaning is one which challenges boundaries and definitions, and that part of this challenge concerns the relationship between the audience and the art work, whether we talk about theater, cinema, photography, or objects. -

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Samuel. 2015. "The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463124 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 A dissertation presented by Samuel Johnson to The Department of History of Art and Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Art and Architecture Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 Samuel Johnson All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Maria Gough Samuel Johnson “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 Abstract Although widely respected as an abstract painter, the Russian Jewish artist and architect El Lissitzky produced more works on paper than in any other medium during his twenty year career. Both a highly competent lithographer and a pioneer in the application of modernist principles to letterpress typography, Lissitzky advocated for works of art issued in “thousands of identical originals” even before the avant-garde embraced photography and film. -

David Quigley Learning to Live: Preliminary Notes for a Program Of

David Quigley In an essay published in 2009, Boris could play in a broader social context influenced the founding director John Groys makes the claim that “today art beyond the narrow realm of the art Andrew Rice, as well as the professors Learning to Live: education has no definite goal, no world. Josef Albers, Merce Cunningham, Robert Preliminary Notes method, no particular content that can Motherwell, John Cage, and the poets be taught, no tradition that can be Performing Pragmatism: Robert Creeley and Charles Olson. for a Program of Art transmitted to a new generation—which Art as Experience Unlike other trajectories of the critique Education for the is to say, it has too many.”69 While one On the first pages of Dewey’s Art as of the art object, the Deweyian tradition might agree with this diagnosis, one Experience from 1934, we read: did not deny the special status of art in 21st Century. immediately wonders how we should itself but rather resituated it within a Après John Dewey assess it. Are we to merely tacitly “By one of the ironic perversities that continuum of human experience. Dewey, acknowledge this situation or does this often attend the course of affairs, the as a thinker of egalitarianism and critique imply a call for change? Is this existence of the works of art upon which democracy, created a theory of art lack (or paradoxical overabundance) of the formation of an aesthetic theory based on the fundamental continuity goals, methods or content inherent to depends has become an obstruction of experience and practice, making the very essence of art education, or is to theory about them. -

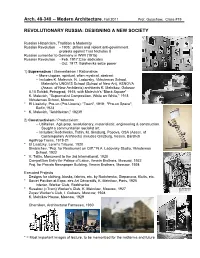

C:\Users\Kai\Documents\CMU Teaching\Modern\Handouts

Arch. 48-340 -- Modern Architecture, Fall 2011 Prof. Gutschow, Class #19 REVOLUTIONARY RUSSIA: DESIGNING A NEW SOCIETY Russian Historicism, Tradition & Modernity Russian Revolution - 1905: strikes and violent anti-government protests against Tsar Nicholas II Russian surrender to Germany in WWI (1915) Russian Revolution - Feb. 1917:Czar abdicates - Oct. 1917: Bolsheviks seize power 1) Suprematism / Elementarism / Rationalism -- More utopian, spiritual, often mystical, abstract -- Includes K. Malevich, N. Ladovsky, Vkhutemas School, Malevich's UNOVIS School (School of New Art), ASNOVA (Assoc. of New Architects) architects K. Melnikov, Golosov 0.10 Exhibit, Petrograd, 1915, with Malevich’s “Black Square” K. Malevich, "Suprematist Composition, White on White," 1918 Vkhutemas School, Moscow * El Lissitzky, Pro-un (Pro-Unovis): "Town", 1919; "Pro-un Space", Berlin,1923 * K. Malevich, "Arkhitekton," 1923ff 2) Constructivism / Productivism: -- Utilitarian, Agit-prop, revolutionary, materialistic, engineering & construction. Sought a communitarian socialist art. -- Includes: Rodchenko, Tatlin, M. Ginsburg, Popova, OSA (Assoc. of Contemporary Architects) includes Ginzburg, Vesnin, Barshch AgitProp Trains, 1919-21 * El Lissitzky, Lenin's Tribune, 1920 Simbirchev, “Proj. for Restaurant on Cliff," N.A. Ladovsky Studio, Vkhutemas School, 1922 * V. Tatlin, Monument to the 3rd International, 1920 Competition Entry for Palace of Labor, Vesnin Brothers, Moscow, 1922 Proj. for Pravda Newspaper Building, Vesnin Brothers, Moscow, 1924 Executed Projects Designs for clothing, kiosks, fabrics, etc. by Rodchenko, Stepanova, Klutis, etc. * Soviet Pavilion at Expo. des Art Décoratifs, K. Melnikov, Paris, 1925 Interior, Worker Club, Rodchenko * Rusakov (=Tram) Worker's Club, K. Melnikov, Moscow, 1927 Zuyev Worker's Club, I. Golosov, Moscow, 1928 K. Melnikov House, Moscow, 1929 Chernikov, Architectural Fantasies, 1930 * = Most important images of lecture, to be memorized for the midterms and future . -

The Distancing-Embracing Model of the Enjoyment of Negative Emotions in Art Reception

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2017), Page 1 of 63 doi:10.1017/S0140525X17000309, e347 The Distancing-Embracing model of the enjoyment of negative emotions in art reception Winfried Menninghaus1 Department of Language and Literature, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, 60322 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected] Valentin Wagner Department of Language and Literature, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, 60322 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected] Julian Hanich Department of Arts, Culture and Media, University of Groningen, 9700 AB Groningen, The Netherlands [email protected] Eugen Wassiliwizky Department of Language and Literature, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, 60322 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected] Thomas Jacobsen Experimental Psychology Unit, Helmut Schmidt University/University of the Federal Armed Forces Hamburg, 22043 Hamburg, Germany [email protected] Stefan Koelsch University of Bergen, 5020 Bergen, Norway [email protected] Abstract: Why are negative emotions so central in art reception far beyond tragedy? Revisiting classical aesthetics in the light of recent psychological research, we present a novel model to explain this much discussed (apparent) paradox. We argue that negative emotions are an important resource for the arts in general, rather than a special license for exceptional art forms only. The underlying rationale is that negative emotions have been shown to be particularly powerful in securing attention, intense emotional involvement, and high memorability, and hence is precisely what artworks strive for. Two groups of processing mechanisms are identified that conjointly adopt the particular powers of negative emotions for art’s purposes. -

Rayonists and Futurists: a Manifesto, 1913

MIKHAIL LARIONOV AND NATALYA GONCHAROVA Rayonists and Futurists: A Manifesto, 1913 For biographies see pp. 79 and 54. The text of this piece, "Luchisty i budushchniki. Manifest," appeared in the miscel- lany Oslinyi kkvost i mishen [Donkey's Tail and Target] (Moscow, July iQn), pp. 9-48 [bibl. R319; it is reprinted in bibl. R14, pp. 175-78. It has been translated into French in bibl. 132, pp. 29-32, and in part, into English in bibl. 45, pp. 124-26]. The declarations are similar to those advanced in the catalogue of the '^Target'.' exhibition held in Moscow in March IQIT fbibl. R315], and the concluding para- graphs are virtually the same as those of Larionov's "Rayonist Painting.'1 Although the theory of rayonist painting was known already, the "Target" acted as tReTormaL demonstration of its practical "acKieveffllBnty' Becau'S^r^ffie^anous allusions to the Knave of Diamonds. "A Slap in the Face of Public Taste," and David Burliuk, this manifesto acts as a polemical гейроп^ ^Х^ШШУ's rivals^ The use of the Russian neologism ШШ^сТиШ?, and not the European borrowing futuristy, betrays Larionov's current rejection of the West and his orientation toward Russian and East- ern cultural traditions. In addition to Larionov and Goncharova, the signers of the manifesto were Timofei Bogomazov (a sergeant-major and amateur painter whom Larionov had befriended during his military service—no relative of the artist Alek- sandr Bogomazov) and the artists Morits Fabri, Ivan Larionov (brother of Mikhail), Mikhail Le-Dantiyu, Vyacheslav Levkievsky, Vladimir Obolensky, Sergei Romano- vich, Aleksandr Shevchenko, and Kirill Zdanevich (brother of Ilya). -

Read Book Kazimir Malevich

KAZIMIR MALEVICH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Achim Borchardt-Hume | 264 pages | 21 Apr 2015 | TATE PUBLISHING | 9781849761468 | English | London, United Kingdom Kazimir Malevich PDF Book From the beginning of the s, modern art was falling out of favor with the new government of Joseph Stalin. Red Cavalry Riding. Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students. The movement did have a handful of supporters amongst the Russian avant garde but it was dwarfed by its sibling constructivism whose manifesto harmonized better with the ideological sentiments of the revolutionary communist government during the early days of Soviet Union. What's more, as the writers and abstract pundits were occupied with what constituted writing, Malevich came to be interested by the quest for workmanship's barest basics. Black Square. Woman Torso. The painting's quality has degraded considerably since it was drawn. Guggenheim —an early and passionate collector of the Russian avant-garde—was inspired by the same aesthetic ideals and spiritual quest that exemplified Malevich's art. Hidden categories: Articles with short description Short description matches Wikidata Use dmy dates from May All articles with unsourced statements Articles with unsourced statements from June Lyubov Popova - You might like Left Right. Harvard doctoral candidate Julia Bekman Chadaga writes: "In his later writings, Malevich defined the 'additional element' as the quality of any new visual environment bringing about a change in perception Retrieved 6 July A white cube decorated with a black square was placed on his tomb. It was one of the most radical improvements in dynamic workmanship. Landscape with a White House. -

The Left Front : Radical Art in the "Red Decade," 1929-1940

LEFT FRONT EVENTS All events are free and open to the public Saturday, January 18, 2pm Winter Exhibition Opening with W. J. T. Mitchell Wednesday, February 5, 6pm Lecture & Reception: Julia Bryan-Wilson, Figurations Wednesday, February 26, 6pm Poetry Reading: Working Poems: An Evening with Mark Nowak Saturday, March 8, 2pm Film Screening and Discussion: Body and Soul with J. Hoberman Saturday, March 15, 2pm Guest Lecture: Vasif Kortun of SALT, Istanbul Thursday, April 3, 6pm Gallery Performance: Jackalope Theatre, Living Newspaper, Edition 2014 Saturday, April 5, 5pm Gallery Performance: Jackalope Theatre, Living Newspaper, Edition 2014 Wednesday, April 16, 2014, 6pm Lecture: Andrew Hemingway, Style of the New Era: THE LEFT FRONT John Reed Clubs and Proletariat Art RADICAL ART IN THE "RED DECADE," 1929-1940 Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art Northwestern University 40 Arts Circle Drive, Evanston, IL, 60208-2140 www.blockmuseum.northwestern.edu Generous support for The Left Front is provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art, as well as the Terra Foundation on behalf of William Osborn and David Kabiller, and the MARY AND LEIGH BLOCK MUSEUM OF ART Myers Foundations. Additional funding is from the Carlyle Anderson Endowment, Mary and Leigh Block Endowment, the Louise E. Drangsholt Fund, the Kessel Fund at the NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSIty Block Museum, and the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. theleftfront-blockmuseum.tumblr.com January 17–June 22, 2014 DIRECTOR'S FOREWORD The Left Front: Radical Art in the “Red Decade”, 1929–1940 was curated by John Murphy undergraduate seminar that focused on themes in the exhibition and culminated in and Jill Bugajski, doctoral candidates in the Department of Art History at Northwestern student essays offering close examinations of particular objects from the show.