Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue Number 1, 2016

Issue Number 1, 2016 A sub-regional UNESCO-ICH project Supported by the Flanders Government SAICH NEWS Senior officials, consultants and coordinators of the SAICH Platform Prof. David J. Simbi Mr. Damir Dijakovic Dr. Thokozile Chitepo Vice Chancellor, Regional Cultural Advisor, Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Rural Development, Promotion and Preservation Chinhoyi University of UNESCO Regional Office of National Cultural Heritage, Zimbabwe Technology for Southern Africa Mr. Stephen Chifunyise Dr. Marc Jacobs Mr. Lovemore Mazibuko UNESCO ICH Expert/ UNESCO ICH Expert/ UNESCO ICH Expert/ Consultant Flanders Government Consultant Representative Prof. Herbert Chimhundu Prof. Jacob Mapara Dr. Manase K. Chiweshe Coordinator Associate Coordinator Associate Coordinator SAICH Platform SAICH Platform SAICH Platform Editor-in-Chief Cover Page Professor Herbert Chimhundu Event: Great Limpopo Cultural Trade Fair, Location: Boli Muhlanguleni, Editor Chiredzi, Zimbabwe, Photograph by: Mr. Eugene Ncube Professor Jacob Mapara Contacts Contributors SAICH Platform Dr Manase K. Chiweshe Chinhoyi University of Technology Ms Varaidzo Chinokwetu P. Bag 7724, Ms Jacqueline Tanhara Chinhoyi Design Off Harare-Kariba Highway Mr. Eugene Ncube Zimbabwe Printing Telephone: +2636727496 CUT Printing Press E-mail: [email protected] | [email protected] SAICH NEWS SAFEGUARDING SAICH NEWS Participating Countries ParticipatingParticipating Countries Countries Participating Countries ParticipatingParticipatingParticipating CountriesCountries Countries BotswanaParticipatingBotswana -

MIDLANDS STATE UNIVERSITY APPROVAL FORM The

MIDLANDS STATE UNIVERSITY APPROVAL FORM The undersigned certify that they have supervised, read and recommend to the Midlands State University for acceptance of dissertation entitled: Violation of Children `s rights by Varemba cultural practise in Mberengwa District 1980-2013 submitted by Nokuthula Bula-Bula in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in History and International studies Honours Degree Signature of Student........................................................................................................................... Signature of Supervisor...................................................................................................................... Signature of the Chairperson............................................................................................................. Signature of the Examiner(s)............................................................................................................. 1 DECLARATION I, Bula-bula Nokuthula (R103446R), certify that this dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Bachelor of Arts honours degree in History and International Studies at Midlands State University has not been submitted for a degree at any other University, and that it is entirely my work. Student’s name Nokuthula.L Bula-Bula Signature ……………………………… Date ........../......../............ 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to thank the almightys God who gave me the wisdom and knowledge to accomplish the work. My appreciation is -

Country Advice Zimbabwe Zimbabwe – ZWE36759 – Movement for Democratic Change – Returnees – Spies – Traitors – Passports – Travel Restrictions 21 June 2010

Country Advice Zimbabwe Zimbabwe – ZWE36759 – Movement for Democratic Change – Returnees – Spies – Traitors – Passports – Travel restrictions 21 June 2010 1. Deleted. 2. Deleted. 3. Please provide a general update on the situation for Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) members, both rank and file members and prominent leaders, in respect to their possible treatment and risk of serious harm in Zimbabwe. The situation for MDC members is precarious, as is borne out by the following reports which indicate that violence is perpetrated against them with impunity by Zimbabwean police and other Law and Order personnel such as the army and pro-Mugabe youth militias. Those who are deemed to be associated with the MDC party either by family ties or by employment are also adversely treated. The latest Country of Origin Information Report from the UK Home Office in December 2009 provides recent chronology of incidents from July 2009 to December 2009 where MDC members and those believed to be associated with them were adversely treated. It notes that there has been a decrease in violent incidents in some parts of the country; however, there was also a suspension of the production of the „Monthly Political Violence Reports‟ by the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum (ZHRF), so that there has not been a comprehensive accounting of incidents: POLITICALLY MOTIVATED VIOLENCE Some areas of Zimbabwe are hit harder by violence 5.06 Reporting on 30 June 2009, the Solidarity Peace Trust noted that: An uneasy calm prevails in some parts of the country, while in others tensions remain high in the wake of the horrific violence of 2008…. -

19 October 2009 Edition

19 October 2009 Edition 017 HARARE-Embattled‘I Deputy Agriculturewill Minister-Designate not quit’He was ordered to surrender his passport and title deeds of Roy Bennett has vowed not to give up politics despite his one of his properties and not to interfere with witnesses. continued ‘persecution and harassment.’ His trial was supposed to start last week on Tuesday at the Magistrate Court, only to be told on the day that the State was “I am here for as long as I can serve my country, my people applying to indict him to the High Court. The application was and my party to the best of my ability. Basically, I am here until granted the following day by Magistrate Lucy Mungwira and we achieve the aspirations of the people of Zimbabwe,” said he was committed to prison. Bennett in an interview on Saturday, quashing any likelihood that he would leave politics soon. On Friday, Justice Charles Hungwe reinstated his bail granted He added: “I have often thought of it (quitting) and it is an by the Supreme Court in March, resulting in his release. easiest thing to do, by the way. But if you have a constituency you have stood in front of and together you have suffered, “It is good to be out again, it is not a nice place (prison) to be. there is no easy walking away from that constituency. There are a lot of lice,” said Bennett. He said he had hoped So basically I am there until we return democracy and that with the transitional government in existence he would freedoms to Zimbabwe.” not continue to be ‘persecuted and harassed”. -

Bulawayo City Mpilo Central Hospital

Province District Name of Site Bulawayo Bulawayo City E. F. Watson Clinic Bulawayo Bulawayo City Mpilo Central Hospital Bulawayo Bulawayo City Nkulumane Clinic Bulawayo Bulawayo City United Bulawayo Hospital Manicaland Buhera Birchenough Bridge Hospital Manicaland Buhera Murambinda Mission Hospital Manicaland Chipinge Chipinge District Hospital Manicaland Makoni Rusape District Hospital Manicaland Mutare Mutare Provincial Hospital Manicaland Mutasa Bonda Mission Hospital Manicaland Mutasa Hauna District Hospital Harare Chitungwiza Chitungwiza Central Hospital Harare Chitungwiza CITIMED Clinic Masvingo Chiredzi Chikombedzi Mission Hospital Masvingo Chiredzi Chiredzi District Hospital Masvingo Chivi Chivi District Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chimombe Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chinyika Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Chitando Rural Health Centre Masvingo Gutu Gutu Mission Hospital Masvingo Gutu Gutu Rural Hospital Masvingo Gutu Mukaro Mission Hospital Masvingo Masvingo Masvingo Provincial Hospital Masvingo Masvingo Morgenster Mission Hospital Masvingo Mwenezi Matibi Mission Hospital Masvingo Mwenezi Neshuro District Hospital Masvingo Zaka Musiso Mission Hospital Masvingo Zaka Ndanga District Hospital Matabeleland South Beitbridge Beitbridge District Hospital Matabeleland South Gwanda Gwanda Provincial Hospital Matabeleland South Insiza Filabusi District Hospital Matabeleland South Mangwe Plumtree District Hospital Matabeleland South Mangwe St Annes Mission Hospital (Brunapeg) Matabeleland South Matobo Maphisa District Hospital Matabeleland South Umzingwane Esigodini District Hospital Midlands Gokwe South Gokwe South District Hospital Midlands Gweru Gweru Provincial Hospital Midlands Kwekwe Kwekwe General Hospital Midlands Kwekwe Silobela District Hospital Midlands Mberengwa Mberengwa District Hospital . -

1 Daily Media Monitoring Report Issue 4: 3 June 2018 Table of Contents

Daily Media Monitoring Report Issue 4: 3 June 2018 Table of Contents 1.1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Key Events .......................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Media Monitored ................................................................................................................. 2 Methodology ............................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 Did the media represent political parties in a fair and balanced manner? .......................... 3 2.1 Space and time dedicated to political parties in private and public media ...................... 3 2.2 Space and time dedicated to political actors in private and public media ....................... 4 2.3 Tone of coverage for political parties .............................................................................. 5 2.4 Gender representation in election programmes ............................................................. 7 2.5 Youth representation in election programmes ................................................................ 8 2.6 Time dedicated to political players in the different programme types in broadcast media .............................................................................................................................................. 9 3.0 Conclusion ....................................................................................................................... -

Midlands Province

School Province District School Name School Address Level Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BARU KUSHINGA PRIMARY BARU KUSHINGA VILLAGE 48 CENTAL ESTATES Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BUSH PARK MUSENA RESETTLEMENT AREA VILLAGE 1 MUSENA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BUSH PARK 2 VILLAGE 5 WARD 19 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CAMBRAI ST MATHIAS LALAPANZI TOWNSHIP CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAKA NDARUZA VILLAGE HEAD CHAKA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAKASTEAD FENALI VILLAGE NYOMBI SIDING Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAMAKANDA TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT SCHEME MVUMA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAPWANYA HWATA-HOLYCROSS ROAD RUDUMA VILLAGE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIHOSHO MATARITANO VILLAGE HEADMAN DEBWE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHILIMANZI NYONGA VILLAGE CHIEF CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIMBINDI CHIMBINDI VILLAGE WARD 5 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHINGEGOMO WARD 18 TOKWE 4 VILLAGE 16 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHINYUNI CHINYUNI WARD 7 CHUKUCHA VILLAGE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIRAYA (WYLDERGROOVE) MVUMA HARARE ROAD WASR 20 VILLAGE 1 Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHISHUKU CHISHUKU VILAGE 3 CHIEF CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHITENDERANO TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT AREA WARD 11 Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWESHE PONDIWA VILLAGE MAPIRAVANA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA CHIWODZA RESETTLEMENT AREA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA NO 2 VILLAGE 66 CHIWODZA CENTRAL ESTATES Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIZVINIRE CHIZVINIRE PRIMARY SCHOOL RAMBANAPASI VILLAGE WARD 4 Primary Midlands -

The Undersigned Authenticate That the the Midlands State University for Assessing Zimbabwean Local Housing: Challenges and Oppor

APPROVAL FORM The undersigned authenticate that they have supervised and recommended to the Midlands State University for acceptance the dissertation entitled: Assessing Zimbabwean Local Authorities` capacity to deliver affordable housing: Challenges and Opportunities. Case Of Kwekwe City Council. Submitted by :Christiner Mjanga Reg. No. R134524H in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Bachelor of Sciences Honours Degree in Local Governance Studies. ..................................................... ...................................................... SUPERVISIOR DATE .................................................... ........................................................ CHAIRPERSON DATE i FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE RELEASE FORM Name of Student: Christiner Mjanga Registration Number: R134524H Dissertation title: Assessing Zimbabwean Local Authorities` capacity to deliver affordable housing- Challenges and Opportunities: Case of Kwekwe City Council. Degree to which Dissertation was presented: Bsc Honours in Local governance studies Year this degree granted: 2016 Permission is hereby granted to the Midlands State University library to produce single copies of this dissertation and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research only. The author reserves other publication rights and neither the dissertation nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author`s written permission. Signed ...................................................... -

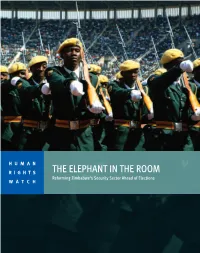

VII. the Unity Government Response

HUMAN RIGHTS THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM Reforming Zimbabwe’s Security Sector Ahead of Elections WATCH The Elephant in the Room Reforming Zimbabwe’s Security Sector Ahead of Elections Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0220 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2013 ISBN: 978-1-62313-0220 The Elephant in the Room Reforming Zimbabwe’s Security Sector Ahead of Elections List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... ii I. Summary ........................................................................................................................ -

How South Africa Can Nudge Zimbabwe Toward Stability

How South Africa Can Nudge Zimbabwe toward Stability Crisis Group Africa Briefing N°164 Johannesburg/Nairobi/Brussels, 17 December 2020 What’s new? As Zimbabwe’s political and economic crises worsen, South Africa is moving beyond its policy of “quiet diplomacy” with its northern neighbour and apply- ing more pressure on Harare to open up political space and reform its economy. Why does it matter? With Zimbabwe’s people slipping further into destitution, crackdowns fostering a growing sense of grievance within the opposition, and politi- cal divisions pitting ruling-party members against one another, the country could tip into even greater crisis through mass unrest or another coup. What should be done? Pretoria should press Harare to halt repression and start dialogue with the political opposition to address Zimbabwe’s economic woes. It should work with Washington on a roadmap for reforms that the U.S. and others can use to guide decisions on reversing sanctions and supporting debt relief for Zimbabwe. I. Overview Three years after a coup ended Robert Mugabe’s rule, the situation in Zimbabwe has gone from bad to worse, as political tensions mount, the economy falls apart and the population faces hunger and COVID-19. Having signalled a desire to stabilise the economy and ease repression, President Emmerson Mnangagwa has disappointed. The state is arresting opponents who protest government corruption and incompe- tence. Meanwhile, government-allied businessmen are tightening their grip on what is left of the economy, while citizens cope with austerity measures and soaring infla- tion. Violence and lawlessness are on the rise. -

Wits ACSUS Media Analysis Sept-Nov 2018.Indd

Africa Media Analysis Report SEPTEMBER - NOVEMBER 2018 Tangaza Africa Media 20 Baker Street, Rosebank 2196 P O Box 1953, Houghton 2041 Tel: +27 11 447 4017 Fax: +27 86 545 7357 email: [email protected] Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 Overall Scorecard 3 Analysis of daily issue coverage, April 2018 4 Eastern Africa & Great Lakes 5 Analysis of daily issue coverage 5 Politics 6 Economy, Trade & Development 7 Peace, Security & Terrorism 8 Health & Food issues 9 Tourism, Travel & Leisure 10 Business & Investments 11 Science, Technology & Innovation 12 Entertainment 13 Education, Arts & Culture 14 Southern Africa 15 Analysis of daily issue coverage 15 Politics 16 Economy, Trade & Development 17 Tourism, Travel & Leisure 18 Health & Food issues 19 Business & Investments 20 Science, Technology & Innovation 21 Peace, Security & Terrorism 22 Entertainment 23 West Africa 24 Analysis of daily issue coverage 24 Politics 25 Economy, Trade & Development 26 Peace, Security & Terrorism 27 Health & Food issues 27 Business & Investments 28 Science, Technology & Innovation 28 Education 29 Entertainment 29 North Africa 30 Analysis of News Categories 30 Peace, Security & Terrorism 31 Politics 51 Economy, Trade & Development 53 2 Overall Scorecard ĂƐƚ tĞƐƚ EŽƌƚŚ ^ŽƵƚŚĞƌŶ dŽƚĂů ĨƌŝĐĂ ĨƌŝĐĂ ĨƌŝĐĂ ĨƌŝĐĂ ;ŶͿ ;ŶͿ ;ŶͿ ;ŶͿ E й WŽůŝƚŝĐƐ ϲϳϯ ϯϱϲ ϱϵϯ ϳϭϱ Ϯ͕ϯϯϳ ϯϱ͘ϳϮ WĞĂĐĞ͕^ĞĐƵƌŝƚLJΘdĞƌƌŽƌŝƐŵ ϱϰϬ ϯϮϲ ϳϳ Ϯϱϲ ϭ͕ϭϵϵ ϭϴ͘ϯϯ ĐŽŶŽŵLJ͕dƌĂĚĞΘĞǀĞůŽƉŵĞŶƚ ϯϱϲ ϰϵ ϮϮϵ ϮϬϵ ϴϰϯ ϭϮ͘ϴϵ ,ĞĂůƚŚΘ&ŽŽĚŝƐƐƵĞƐ ϮϮϳ ϭϬ ϴϯ ϮϱϮ ϱϳϮ ϴ͘ϳϰ dŽƵƌŝƐŵ͕dƌĂǀĞůΘ>ĞŝƐƵƌĞ Ϯϲϯ ϲϴ ϭϬϯ ϴϯ ϱϭϳ ϳ͘ϵϬ ƵƐŝŶĞƐƐΘ/ŶǀĞƐƚŵĞŶƚƐ -

The Food Poverty Atlas

Zimbabwe Food Poverty Atlas2016_FINAL.qxp_Layout 1 4/10/2016 10:44 Page 1 The Food Poverty Atlas SMALL AREA FOOD POVERTY ESTIMATION Statistics for addressing food and nutrition insecurity in Zimbabwe SEPTEMBER, 2016 Zimbabwe Food Poverty Atlas2016_FINAL.qxp_Layout 1 4/10/2016 10:44 Page 2 2 Zimbabwe Food Poverty Atlas2016_FINAL.qxp_Layout 1 4/10/2016 10:44 Page i The Food Poverty Atlas SMALL AREA FOOD POVERTY ESTIMATION Statistics for addressing food and nutrition insecurity in Zimbabwe SEPTEMBER, 2016 i Zimbabwe Food Poverty Atlas2016_FINAL.qxp_Layout 1 4/10/2016 10:44 Page ii © UNICEF Zimbabwe, The World Bank and Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency 20th Floor, Kaguvi Building, Cnr 4th Street and Central Avenue, Harare, Zimbabwe P.O. Box CY342, Causeway, Harare, Zimbabwe. Tel: (+263-4) 706681/8 or (+263-4) 703971/7 Fax: (+263-4) 762494 E-mail: [email protected] This publication is available on the following websites: www.unicef.org/zimbabwe www.worldbank.org/ www.zimstat.co.zw/ ISBN: 978-92-806-4824-9 The Food Poverty Atlas was produced by the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT). Technical and financial support was provided by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Bank Design and layout: K. Moodie Photographs by: © UNICEF/2015/T. Mukwazhi ii Zimbabwe Food Poverty Atlas2016_FINAL.qxp_Layout 1 4/10/2016 10:44 Page iii Food poverty prevalence at a glance Map 1: Food poverty prevalence by district* Figure 1 400,000 Number of food poor 350,000 and non poor households 300,000 250,000 by province* 200,000 150,000 100,000 50,000 0 Harare Central N.B 1.