How South Africa Can Nudge Zimbabwe Toward Stability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ms Modise Came to Listen NCOP Chairperson Meets Mpondomise Royal Council Vision

Parliament: Following up on our commitments to the people. Vol. 16 ISSUE 9 2016 Ms Modise came to listen NCOP Chairperson meets Mpondomise Royal Council Vision An activist and responsive people’s Parliament that improves the quality of life of South Africans and ensures enduring equality in our society. Mission Parliament aims to provide a service to the people of South Africa by providing the following: • A vibrant people’s Assembly that intervenes and transforms society and addresses the development challenges of our people; • Effective oversight over the Executive by strengthening its scrutiny of actions against the needs of South Africans; Provinces of Council National of • Participation of South Africans in the decision-making of National Assembly National of processes that affect their lives; • A healthy relationship between the three arms of the Black Rod Mace Mace State, that promotes efficient co-operative governance between the spheres of government, and ensures appropriate links with our region and the world; and • An innovative, transformative, effective and efficient parliamentary service and administration that enables Members of Parliament to fulfil their constitutional responsibilities. Strategic Objectives 1. Strengthening oversight and accountability 2. Enhancing public involvement 3. Deepening engagement in international fora 4. Strengthening co-operative government 5. Strengthening legislative capacity contents m essage 5 FrOm natiOnal AsseMBly 6 highlights FrOm the Committee rooms This is a summary of a selection -

19 October 2009 Edition

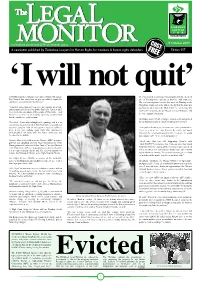

19 October 2009 Edition 017 HARARE-Embattled‘I Deputy Agriculturewill Minister-Designate not quit’He was ordered to surrender his passport and title deeds of Roy Bennett has vowed not to give up politics despite his one of his properties and not to interfere with witnesses. continued ‘persecution and harassment.’ His trial was supposed to start last week on Tuesday at the Magistrate Court, only to be told on the day that the State was “I am here for as long as I can serve my country, my people applying to indict him to the High Court. The application was and my party to the best of my ability. Basically, I am here until granted the following day by Magistrate Lucy Mungwira and we achieve the aspirations of the people of Zimbabwe,” said he was committed to prison. Bennett in an interview on Saturday, quashing any likelihood that he would leave politics soon. On Friday, Justice Charles Hungwe reinstated his bail granted He added: “I have often thought of it (quitting) and it is an by the Supreme Court in March, resulting in his release. easiest thing to do, by the way. But if you have a constituency you have stood in front of and together you have suffered, “It is good to be out again, it is not a nice place (prison) to be. there is no easy walking away from that constituency. There are a lot of lice,” said Bennett. He said he had hoped So basically I am there until we return democracy and that with the transitional government in existence he would freedoms to Zimbabwe.” not continue to be ‘persecuted and harassed”. -

News Covering in the Online Press Media During the ANC Elective Conference of December 2017 Tigere Paidamoyo Muringa 212556107

News covering in the online press media during the ANC elective conference of December 2017 Tigere Paidamoyo Muringa 212556107 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the academic requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) at Centre for Communication, Media and Society in the School of Applied Human Sciences, College of Humanities, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban. Supervisor: Professor Donal McCracken 2019 As the candidate's supervisor, I agree with the submission of this thesis. …………………………………………… Professor Donal McCracken i Declaration - plagiarism I, ……………………………………….………………………., declare that 1. The research reported in this thesis, except where otherwise indicated, is my original research. 2. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. 3. This thesis does not contain other persons' data, pictures, graphs or other information unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other persons. 4. This thesis does not contain other persons' writing unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other researchers. Where other written sources have been quoted, then: a. Their words have been re-written, but the general information attributed to them has been referenced b. Where their exact words have been used, then their writing has been placed in italics and inside quotation marks and referenced. 5. This thesis does not contain text, graphics or tables copied and pasted from the Internet, unless specifically acknowledged, and the source being detailed in the thesis and the References sections. Signed ……………………………………………………………………………… ii Acknowledgements I am greatly indebted to the discipline of CCMS at Howard College, UKZN, led by Professor Ruth Teer-Tomaselli. It was the discipline’s commitment to academic research and academic excellence that attracted me to pursue this degree at CCMS (a choice that I don’t regret). -

1 Daily Media Monitoring Report Issue 4: 3 June 2018 Table of Contents

Daily Media Monitoring Report Issue 4: 3 June 2018 Table of Contents 1.1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Key Events .......................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Media Monitored ................................................................................................................. 2 Methodology ............................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 Did the media represent political parties in a fair and balanced manner? .......................... 3 2.1 Space and time dedicated to political parties in private and public media ...................... 3 2.2 Space and time dedicated to political actors in private and public media ....................... 4 2.3 Tone of coverage for political parties .............................................................................. 5 2.4 Gender representation in election programmes ............................................................. 7 2.5 Youth representation in election programmes ................................................................ 8 2.6 Time dedicated to political players in the different programme types in broadcast media .............................................................................................................................................. 9 3.0 Conclusion ....................................................................................................................... -

The 2020 National Budget Speech

Embargoed till end of delivery ZIMBABWE THE 2020 NATIONAL BUDGET SPEECH “Gearing for Higher Productivity, Growth and Job Creation” Presented to the Parliament of Zimbabwe on November 14, 2019 By The Hon. Prof. Mthuli Ncube Minister of Finance & Economic Development MOTION 1. Mr Speaker Sir, I move that leave be granted to present a Statement of the Estimated Revenues and Expenditures of the Republic of Zimbabwe for the 2020 Financial Year and to make Provisions for matters ancillary and incidental to this purpose. INTRODUCTION 2. Mr Speaker Sir, allow me to start by thanking the President –His Excellency, E. D. Mnangagwa, and the Honourable Vice Presidents, Cde Kembo Mohadi and Cde Constantino Chiwenga, for their valuable leadership and guidance as we advance the necessary reforms geared towards achieving Vision 2030. The President’s vision and political will has facilitated the implementation of a number of bold policy measures, under a challenging economic environment. This was clear from the State of the Nation Address by His Excellency on 1 October 2019. 3. Concurrently, I wish to appreciate the cooperation and contributions received from my colleagues, Honourable Ministers in Cabinet and look forward to their continued engagement as we implement this 2020 Budget. 3 4. Mr Speaker Sir, allow me to also express my indebtedness for the support I have received from this August House through its oversight functions. In particular, I have benefited immensely from the contributions of the Budget, Finance and Investment Portfolio Committee, Public Accounts Committee as well as other Portfolio Committees. 5. The recent engagement with all the Portfolio Committees of this August House during the 2020 Parliamentary Pre Budget Seminar, held in Victoria Falls over the period 31st October – 3rd November, 2019, facilitated very useful in-depth discussions and recommendations. -

We Marched, Now What?

By Monica Cheru-Mpambawashe 18 November 2017. A day that polarised Zimbabweans. The majority of Harareans heeded the call to march for Robert Gabriel Mugabe to resign after 37 years in power. People who had never attended a single political gathering came out from the suburbs, the ghettos, everywhere. “I had to play my part in putting paid to the ever increasing horrific prospect of his loose cannon mouthed wife, Grace becoming our next president,” said Tatenda Shava (27) of Highlands, one of the affluent areas of Harare. This was the “Walk” crew. Zimbabwe had been simmering for some time. The economic downturn was worsening by the day. But the ruling party leadership was focused on its own factional fights instead of looking at the plight of the people. In a perfect world no one would have wanted the army to step in. But they did and there was no turning back. Rumours of the regional block Southern African Development Community (SADC) intervention to prop Mugabe’s continued rule galvanised the people. Anything, even the army, had to be better than that. But even then, there was a small number who were warning that unwary citizens were celebrating a military coup and would soon live to yearn for the return of Mugabe. Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa, the deposed Vice President, and his miltary handlers would turn on the citizens and cause us untold suffering. Someone quickly labelled these naysayers the “Woke Brigade”. ‘Why join ZANU in their rejuvenation?’one of them, a Zimbabwean writer, asked. Despite this, Mugabe was toppled and Mnangagwa is now the interim President. -

Wits ACSUS Media Analysis Sept-Nov 2018.Indd

Africa Media Analysis Report SEPTEMBER - NOVEMBER 2018 Tangaza Africa Media 20 Baker Street, Rosebank 2196 P O Box 1953, Houghton 2041 Tel: +27 11 447 4017 Fax: +27 86 545 7357 email: [email protected] Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 Overall Scorecard 3 Analysis of daily issue coverage, April 2018 4 Eastern Africa & Great Lakes 5 Analysis of daily issue coverage 5 Politics 6 Economy, Trade & Development 7 Peace, Security & Terrorism 8 Health & Food issues 9 Tourism, Travel & Leisure 10 Business & Investments 11 Science, Technology & Innovation 12 Entertainment 13 Education, Arts & Culture 14 Southern Africa 15 Analysis of daily issue coverage 15 Politics 16 Economy, Trade & Development 17 Tourism, Travel & Leisure 18 Health & Food issues 19 Business & Investments 20 Science, Technology & Innovation 21 Peace, Security & Terrorism 22 Entertainment 23 West Africa 24 Analysis of daily issue coverage 24 Politics 25 Economy, Trade & Development 26 Peace, Security & Terrorism 27 Health & Food issues 27 Business & Investments 28 Science, Technology & Innovation 28 Education 29 Entertainment 29 North Africa 30 Analysis of News Categories 30 Peace, Security & Terrorism 31 Politics 51 Economy, Trade & Development 53 2 Overall Scorecard ĂƐƚ tĞƐƚ EŽƌƚŚ ^ŽƵƚŚĞƌŶ dŽƚĂů ĨƌŝĐĂ ĨƌŝĐĂ ĨƌŝĐĂ ĨƌŝĐĂ ;ŶͿ ;ŶͿ ;ŶͿ ;ŶͿ E й WŽůŝƚŝĐƐ ϲϳϯ ϯϱϲ ϱϵϯ ϳϭϱ Ϯ͕ϯϯϳ ϯϱ͘ϳϮ WĞĂĐĞ͕^ĞĐƵƌŝƚLJΘdĞƌƌŽƌŝƐŵ ϱϰϬ ϯϮϲ ϳϳ Ϯϱϲ ϭ͕ϭϵϵ ϭϴ͘ϯϯ ĐŽŶŽŵLJ͕dƌĂĚĞΘĞǀĞůŽƉŵĞŶƚ ϯϱϲ ϰϵ ϮϮϵ ϮϬϵ ϴϰϯ ϭϮ͘ϴϵ ,ĞĂůƚŚΘ&ŽŽĚŝƐƐƵĞƐ ϮϮϳ ϭϬ ϴϯ ϮϱϮ ϱϳϮ ϴ͘ϳϰ dŽƵƌŝƐŵ͕dƌĂǀĞůΘ>ĞŝƐƵƌĞ Ϯϲϯ ϲϴ ϭϬϯ ϴϯ ϱϭϳ ϳ͘ϵϬ ƵƐŝŶĞƐƐΘ/ŶǀĞƐƚŵĞŶƚƐ -

China ‘Threatens Zimbabwe President for Looking West’

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 11/20/2019 1:14:11 PM hePrm Resign or face action — China ‘threatens Zimbabwe President for looking West’ Beijing has reportedly asked Zimbabwe President Emmerson Mnangagwa to hand over power to China-leaning Vice-President Constantino Chiwenga. SRIJAN SHUKLA 14 November, 2019 7:12 pm 1ST New Delhi: The Chinese government has told Zimbabwe President Emmerson Mnangagwa to either “resign or retire” from office or face “political action” from Beijing, according to a report in Spotlight Zimbabwe, an online media publication. The report said Beijing has also asked Mnangagwa to hand over power to China-leaning Vice-President General Constantino Chiwenga (Retd), who has been in China since July for medical treatment. Reports suggest that China was responsible for promoting Mnangagwa as Vice-President in 2015 during the presidency of the late Robert Mugabe, who was deposed in 2017 after nearly four decades in power. Now, Beijing is said to be displeased with Mnangagwa for slowly walking away from Zimbabwe’s “Look East Policy” and refusing to grant several development projects to Chinese firms. DISSEMINATED BY MERCURY PUBLIC AFFAIRS, LLC, A REGISTERED FOREIGN AGENT, ON BEHALF OF THE MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE OF ZIMBABWE. MORE INFORMATION IS ON FILE WITH THE DEPT. OF JUSTICE, WASHINGTON, DC Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 11/20/2019 1:14:11 PM Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 11/20/2019 1:14:11 PM For a long time, smaller nations have been anxious about China’s “debt-trap diplomacy”, especially through its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative, but such overt interference by the Asian giant in another country’s domestic politics is unheard of. -

'Reporter Voice' and 'Objectivity'

THE ‘REPORTER VOICE’ AND ‘OBJECTIVITY’ IN CROSS- LINGUISTIC REPORTING OF ‘CONTROVERSIAL’ NEWS IN ZIMBABWEAN NEWSPAPERS. AN APPRAISAL APPROACH BY COLLEN SABAO Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University SUPERVISOR: PROF MW VISSER MARCH 2013 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za ii DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 17 September 2012 Copyright © 2013 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za iii ABSTRACT The dissertation is a comparative analysis of the structural (generic/cognitive) and ideological properties of Zimbabwean news reports in English, Shona and Ndebele, focusing specifically on the examination of the proliferation of authorial attitudinal subjectivities in ‘controversial’ ‘hard news’ reports and the ‘objectivity’ ideal. The study, thus, compares the textuality of Zimbabwean printed news reports from the English newspapers (The Herald, Zimbabwe Independent and Newsday), the Shona newspaper (Kwayedza) and the Ndebele newspaper (Umthunywa) during the period from January 2010 to August 2012. The period represents an interesting epoch in the country’s political landscape. It is a period characterized by a power- sharing government, a political situation that has highly polarized the media and as such, media stances in relation to either of the two major parties to the unity government, the Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front (ZANU PF) and the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC-T). -

URGENT Ms Baleka Mbete Speaker of the National Assembly by Fax: 021 461 9462 by Email: [email protected] Dear Speaker A

URGENT Ms Baleka Mbete Speaker of the National Assembly By fax: 021 461 9462 By email: [email protected] 10 Fricker Road, Illovo Boulevard Johannesburg, 2196 PO Box 61771, Marshalltown Johannesburg, 2107, South Africa Docex 26 Johannesburg T +27 11 530 5000 F +27 11 530 5111 www.webberwentzel.com Your reference Our reference Date D Milo / S Scott 14 April 2015 2583744 Dear Speaker APPOINTMENT PROCESS FOR THE INSPECTOR-GENERAL OF INTELLIGENCE BY THE JOINT STANDING COMMITTEE FOR INTELLIGENCE 1. As you are already aware, we act for the M&G Centre for Investigative Journalism ("amaBhungane"). We confirm that we also act for the Right2Know Campaign ("Right2Know"), the Council for the Advancement of the South African Constitution ("CASAC") and the Institute for Security Studies ("ISS") (collectively "our clients"). 2. We understand that the Joint Standing Committee on Intelligence ("the Committee") is still in the process of appointing the new Inspector-General of Intelligence ("IGI") in terms of section 210(b) of the Constitution and section 7 of the Intelligence Services Oversight Act 40 of 1994 ("the Act"). We are instructed that the interview process of shortlisted candidates commenced on 17 March 2015 in closed proceedings. 3. Moreover, we understand that the Committee has now finalised its consideration of the matter and will soon be reporting to the National Assembly in relation to its nominated candidate, in terms of section 7(1)(b) of the Act (see in this regard a letter from the Chairperson of the National Council of Provinces to the Right2Know Campaign, dated 30 March 2015 and annexed hereto marked "A"). -

Political Culture in the New South Africa

Political Culture in the New South Africa 7 September 2005 Sunnyside Park Hotel, Parktown, Johannesburg South Africa KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG • SEMINAR REPORT • NO 16 • JOHANNESBURG • OCTOBER 2006 © KAS, 2006 All rights reserved While copyright in this publication as a whole is vested in the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, copyright in the text rests with the individual authors, and no paper may be reproduced in whole or part without the express permission, in writing, of both authors and the publisher. It should be noted that any opinions expressed are the responsibility of the individual authors and that the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung does not necessarily subscribe to the opinions of contributors. ISBN: 0-620-37571-X Published by: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 60 Hume Road Dunkeld 2196 Johannesburg Republic of South Africa PO Box 1383 Houghton 2041 Johannesburg Republic of South Africa Telephone: (+27 +11) 214-2900 Telefax: (+27 +11) 214-2913/4 E-mail: [email protected] www.kas.org.za Editing, DTP and production: Tyrus Text and Design Printing: Stups Printing Foreword THE AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENTISTS GABRIEL ALMOND AND SIDNEY VERBA HAVE, MORE THAN anyone else, attempted to define the term political culture. According to them: Political culture is the pattern of individual attitudes and orientations towards politics among the members of a political system. It is the subjective realm that underlies and gives meaning to political actions.1 Although this definition captures succinctly what political culture is, it falls short in differentiating between the political culture that exists at an elite level and the political culture that exists among the citizens of a given system. -

Zimbabwe Democracy Institute (Zdi) Access to Public Health

ZIMBABWE DEMOCRACY INSTITUTE (ZDI) ACCESS TO PUBLIC HEALTH MONTHLY MONITORING REPORT AUGUST 2021 ABUSE OF COVID-19 FUNDS: A CASE OF A PANDEMIC IN A PANDEMIC Source: ZDI 2021, Dataset from Ministry of Health and Child Care Covid-19 daily Situation Reports, 26/08/2021 About the Zimbabwe Democracy Institute (ZDI) The Zimbabwe Democracy Institute (ZDI) is a politically independent and not for profit public policy think-tank based in Zimbabwe. Founded and registered as a trust in terms of the laws of Zimbabwe in November 2012, ZDI serves to generate and disseminate innovative ideas, cutting-edge research and policy analysis to advance democracy, development, good governance and human rights in Zimbabwe. The institute also aims to promote open, informed and evidence-based debate by bringing together pro-democracy experts to platforms for debate. The idea is to offer new ideas to policy makers with the view to entrenching democratic practices in Zimbabwe. The ZDI researches, publishes and conducts national policy debates and conferences in democratization, good governance, public policy, human rights and transitional justice, media and democracy relations, electoral politics and international affairs. nd Zimbabwe Democracy Institute (ZDI) - 66 Jason Moyo Avenue, 2 Floor Bothwell House, Harare, Zimbabwe Introduction 2021, Covid-19 infections in Zimbabwe stood at 108 860 and deaths were 3 532.1 From this date The month of August 2021 saw the Auditor to 26 August 2021, Zimbabwe sustained a 13.8% General’s latest special audit report on the increase in infection as it stood at 123 986 financial management and utilization of public infections2.