Chapter 1 - the Changing Face of Hampton Hill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HA16 Rivers and Streams London's Rivers and Streams Resource

HA16 Rivers and Streams Definition All free-flowing watercourses above the tidal limit London’s rivers and streams resource The total length of watercourses (not including those with a tidal influence) are provided in table 1a and 1b. These figures are based on catchment areas and do not include all watercourses or small watercourses such as drainage ditches. Table 1a: Catchment area and length of fresh water rivers and streams in SE London Watercourse name Length (km) Catchment area (km2) Hogsmill 9.9 73 Surbiton stream 6.0 Bonesgate stream 5.0 Horton stream 5.3 Greens lane stream 1.8 Ewel court stream 2.7 Hogsmill stream 0.5 Beverley Brook 14.3 64 Kingsmere stream 3.1 Penponds overflow 1.3 Queensmere stream 2.4 Keswick avenue ditch 1.2 Cannizaro park stream 1.7 Coombe Brook 1 Pyl Brook 5.3 East Pyl Brook 3.9 old pyl ditch 0.7 Merton ditch culvert 4.3 Grand drive ditch 0.5 Wandle 26.7 202 Wimbledon park stream 1.6 Railway ditch 1.1 Summerstown ditch 2.2 Graveney/ Norbury brook 9.5 Figgs marsh ditch 3.6 Bunces ditch 1.2 Pickle ditch 0.9 Morden Hall loop 2.5 Beddington corner branch 0.7 Beddington effluent ditch 1.6 Oily ditch 3.9 Cemetery ditch 2.8 Therapia ditch 0.9 Micham road new culvert 2.1 Station farm ditch 0.7 Ravenbourne 17.4 180 Quaggy (kyd Brook) 5.6 Quaggy hither green 1 Grove park ditch 0.5 Milk street ditch 0.3 Ravensbourne honor oak 1.9 Pool river 5.1 Chaffinch Brook 4.4 Spring Brook 1.6 The Beck 7.8 St James stream 2.8 Nursery stream 3.3 Konstamm ditch 0.4 River Cray 12.6 45 River Shuttle 6.4 Wincham Stream 5.6 Marsh Dykes -

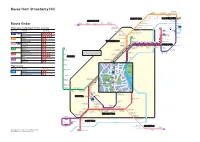

Buses from Strawberry Hill

Buses from Strawberry Hill Hammersmith Stamford Brook Hammersmith Grove Gunnersbury Bus Garage for Hammersmith & City line Turnham Green Ravenscourt Church Park Kew Bridge for Steam Museum 24 hour Brentford Watermans Arts Centre HAMMERSMITH 33 service BRENTFORD Hammersmith 267 Brentford Half Acre Bus Station for District and Piccadilly lines HOUNSLOW Syon Park Hounslow Hounslow Whitton Whitton Road River Thames Bus Station Treaty Centre Hounslow Church Admiral Nelson Isleworth Busch Corner 24 hour Route finder 281 service West Middlesex University Hospital Castelnau Isleworth War Memorial N22 Twickenham Barnes continues to Rugby Ground R68 Bridge Day buses including 24-hour services Isleworth Library Kew Piccadilly Retail Park Circus Bus route Towards Bus stops London Road Ivy Bridge Barnes Whitton Road Mortlake Red Lion Chudleigh Road London Road Hill View Road 24 hour service ,sl ,sm ,sn ,sp ,sz 33 Fulwell London Road Whitton Road R70 Richmond Whitton Road Manor Circus ,se ,sf ,sh ,sj ,sk Heatham House for North Sheen Hammersmith 290 Twickenham Barnes Fulwell ,gb ,sc Twickenham Rugby Tavern Richmond 267 Lower Mortlake Road Hammersmith ,ga ,sd TWICKENHAM Richmond Road Richmond Road Richmond Road Richmond Twickenham Lebanon Court Crown Road Cresswell Road 24 hour Police Station 281 service Hounslow ,ga ,sd Twickenham RICHMOND Barnes Common Tolworth ,gb ,sc King Street Richmond Road Richmond Road Richmond Orleans Park School St Stephen’s George Street Twickenham Church Richmond 290 Sheen Road Staines ,gb ,sc Staines York Street East Sheen 290 Bus Station Heath Road Sheen Lane for Copthall Gardens Mortlake Twickenham ,ga ,sd The yellow tinted area includes every Sheen Road bus stop up to about one-and-a-half Cross Deep Queens Road for miles from Strawberry Hill. -

Please Enter Name Here

Audit and Risk Annual Sustainability Report for the Year Ended 31st March 2018. Distribution The Audit & Risk Committee The Executive Board The NAO The Board of Trustees Issued: May 2018 Andrew Favell (Health, Safety and Environment Adviser) Sustainability Report 2017/18 1. Basis of Opinion The overall rating remains as Good, as the various reports that have been collected on all of our key sustainability themes have improved year on year. 2. Sustainability Strategy A sustainability strategy has been developed and agreed in 2017/18 with key stakeholders across HRP Directorates to further focus on six key areas of sustainability, with a sponsor on the Executive Board. Regular sustainability group meetings are being held to embed the strategy into the organisation and an agenda item for sustainability will remain on the quarterly local Fire, Health and Safety Committee meetings. 3. Conserve Water This year saw a 3% decrease in water consumption at HRP. All sites continue the progress that has been made over the years, and which is now supported by regular environmental audit and impact assessments for all HRP sites. Initiatives have included: The installation of automated meter readings across the main palaces; which has enabled close monitoring of water leaks and allowed prompt repair. Grey water used at some sites where possible to irrigate and flush some of the public toilets. Some visitor toilets have been fitted with sensor taps The water pressure was reduced at the taps, thereby reducing overall consumption at some sites. Rain water and river water is used for irrigation where possible. Visitor urinals have been fitted with an electrical flow rate controller at some sites. -

Village Plan – Hampton

HAMPTON Draft Supplementary Planning Document I March 2017 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Planning Policy and Wider Context 3. Spatial Context 4. Vision for Hampton 5. Objectives 6. Character Area Assessments Character Area 1: Longford River Estates Character Area 2: Queenswood Avenue Estate and west of Hanworth Road Character Area 3: Gloucester Road and the Ormonds Character Area 4: Hampton Village Conservation Area Character Area 5: Hampton Court Green Conservation Area Character Area 6: Hampton Court Park Conservation Area CharacterArea 7: Platt’s Eyot Conservation Area Character Area 8: Hampton Waterworks Character Area 9: Oldfield Road Character Area 10: Priory Road West Character Area 11: Priory Road East and Surroundings Character Area 12: Oak Avenue Estates Character Area 13: Hanworth Road Conservation Area 7. Features and Materials 8. Guidance for Development Sites 9. Shop Front Guidance 10. Forecourt Parking 11. Flood Risk Appendix 1: Relevant Policies and Guidance 1. Introduction The purpose of this Village Planning Guidance Supplementary Planning The London Borough of Richmond Document (SPD) is primarily to establish upon Thames has been divided into a vision and planning policy aims for the a series of smaller village areas. area, in light of existing and emerging Each village is distinctive in terms of Local Plan policy. The SPD intends the community, facilities and local character – as are many sub areas to define, maintain and enhance the within the villages. character of Hampton, and to provide guidance in this regard. The SPD forms The villages of the London Borough part of the wider Village Plan. Richmond upon Thames are attractive with many listed buildings By identifying key features of the village, and Conservation Areas, the local the SPD clarifies the most important character of each being unique, aspects and features that contribute to recognisable and important to the local character to guide those seeking community and to the aesthetic of to make changes to their properties or the borough as a whole. -

AA/Wellington House SUBJECT to CONTRACT DATE AS POSTMARK Dear Sir/Madam, WELLINGTON HOUSE, 209-217 HIGH STREET, HAMPT

Our ref: AA/Wellington House SUBJECT TO CONTRACT DATE AS POSTMARK Dear Sir/Madam, WELLINGTON HOUSE, 209-217 HIGH STREET, HAMPTON HILL Following the successful letting of the ground floor, we can now offer the following office accommodation within this superb air-conditioned office building. FLOOR SUITE USE SQ FT SQ M First 1 Office 900 83 First 2 Office 1,300 121 First 3 Office 1,600 148.6 Ground (left rear) 4 Office 312 29 Total approx 4,112 382 The accommodation is available on flexible sub leases for a term to be agreed at an annual rent of £19.50 per sq ft per annum exclusive. For further information please do not hesitate to contact Andrew Armiger of Cattaneo Commercial on 020 8546 2166 or our Joint Agents Martin Campbell. Yours faithfully Andrew Armiger Cattaneo Commercial Enc. Newly refurbished high specification wellington office suites with 12 car spaces TO LET 312 – 5,257 sqft (29 - 488 sqm) approx house 209-217 HIGH STREET HAMPTON HILL MIDDX TW12 1NP A406 CENTRAL 15 4 M4 1 LONDON A305 wellington 6 3 4a A4 A205 M25 RICHMOND Heathrow A316 TWICKENHAM house A30 A305 A307 13 A310 WANDSWORTH A313 A308 A23 A312 TEDDINGTON A30 STAINES 1 A3 209-217 HIGH STREET HAMPTON HILL MIDDX TW12 1NP HAMPTON MORDEN A308 KINGSTON A24 UPON THAMES 12 M3 A307 CROYDON A307 SUTTON WEYBRIDGE ESHER REFURBISHED OPEN PLAN OFFICES A3 EPSOM 10 A23 WOKING 9 M25 9 7 • FULL AIR CONDITIONING. • IMPRESSIVE ENTRANCE / RECEPTION AREA. A3 7/8 • SUSPENDED CEILINGS WITH • PASSENGER LIFT. A24 8 GUILDFORD REIGATE M23 RECESSED CATEGORY II LIGHTING. -

Hampton Village Consultation Material

Hampton Village INTRODUCTION TO VILLAGE PLANNING GUIDANCE FOR HAMPTON What is Village Planning Guidance? How can I get involved? London Borough of Richmond upon Thames (LBRuT) wants residents and businesses to help prepare ‘Village Planning There will be two different stages of engagement and consultation Guidance’ for the Hampton Village area. This will be a before the guidance is adopted. document that the Council considers when deciding on planning During February and March residents and businesses are being asked applications. Village Planning Guidance can: about their vision for the future of their area, thinking about: • Help to identify what the ‘local character’ of your area is and • the local character what features need to be retained. • heritage assets • Help protect and enhance the local character of your area, • improvement opportunities for specific sites or areas particularly if it is not a designated ‘Conservation Area’. • other planning policy or general village plan issues • Establish key design principles that new development should respond to. Draft guidance will be developed over the summer based on your views and a formal (statutory) consultation carried out in late The boundary has been based on the Village Plan area to reflect summer/autumn 2016 before adoption later in the year. the views of where people live, as well as practical considerations to support the local interpretation of planning policy. How does Village Planning Guidance work? How does the ‘Village Planning Guidance’ relate to Village Plans? The Village Planning Guidance will become a formal planning policy ‘Supplementary Planning Document’ (SPD) which The Planning Guidance builds on the ‘Village Plans’ which were the Council will take account of when deciding on planning developed from the 2010 ‘All in One’ survey results, and from ongoing applications, so it will influence developers and householders consultation, including through the engagement events currently in preparing plans and designs. -

Draft Trustees Report 10/11

IMPACT REPORT 2014 - 2015 SPEAR Impact Report 2014 – 15 1 | P a g e Contents Letter from the Chair and Chief Executive 3 Part 1: an overview Our strategy 4 Our purpose, approach and values 4 Homelessness: a problem that isn’t going away 5 Highlights of 2014/15 6 New service developments: continuing our pioneering role 7 Community involvement: how SPEAR is spreading the word 8 Part 2: a closer look at key areas of our work Working with young people 9 Working with women 9 Promoting health and wellbeing 10 Progression to employment 11 Partnering in community safety 12 Running a volunteering programme 13 Thanks from SPEAR 14 SPEAR Impact Report 2014 – 15 2 | P a g e Letter from the Chair and Chief Executive SPEAR has continued to build its effective and unique response to increased street homelessness. We have seen a further increase in the number of people sleeping rough this year and a steep increase in the number of people struggling with other types of homelessness. The proportion of our clients with complex health and social care needs has increased again and we are concerned by the rising number of street homeless women and young people in our services. In a context of continued funding cuts across the homelessness sector, we are pleased that our income has remained consistent this year. This allows us to continue to deliver our strategic aims of helping the most vulnerable people in our community effectively – people who have often failed to engage with alternative support and who struggle to access mainstream services. -

The Big Breakfast Page 4

FEBRUARY 2016 the stjames-hamptonhill.org.ukspire FREE please take a copy The Big Breakfast Page 4 Start your day the Fairtrade way AROUND THE SPIRE P5 A-Z SACRED PLACES P6 WHAT’S ON P7 Our Church From the Editor... Registered Charity No 1129286 This year promises to be an exciting one for us with Clergy Jacky Cammidge being priested in July and the appointment of a new vicar. Vicar Each year we review the articles in our magazine and Vacant forward plan for the coming year. The 10 Favourites All enquiries regarding page has proved so popular that we are able to continue baptisms, weddings and for a third year as many people have offered to do funerals should go through articles. We also have some very interesting centre- the Parish Office. spreads planned. One new article will appear to replace the recipes which Griselda Barrett produced so expertly for two years. We shall be running a feature called A-Z of Sacred Places on Page 6 which Laurence Sewell has agreed to write for us. It doesn’t seem possible that daffodils and snowdrops were out even before Christmas Curate with the very warm weather. This year everything happens early and this edition has The Revd Jacky Cammidge details of our Lent services and the popular Lent group meetings as well as two parish Jacky, pictured right, was born in Abertillery, meals, one in the church hall on Sunday 7 February, the other on Shrove Tuesday, 9 South Wales. She is a self-supporting February. Do support them if you can. -

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 29Rn JANUARY 1993 1695

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 29rn JANUARY 1993 1695 A copy of the Order, and of the Council's statement of reasons for Private and Independent Schools making the Order together with plans showing the lengths of road 1. Athelstan House, Percy Road, Hampton. affected can be seen at: 2. Broomfield House, Broomfield Road, Kew. (a) the offices of the Chief Officer, Planning, Transport and Client 3. Denmead, Wensleydale Road, Hampton. Services, Civic Centre, (Second Floor), 44 York Street, 4. Hampton, Hanworth Road, Hampton. Twickenham between 9.15 a.m. and 5 pjn. Mondays to 5. Kew College, Cumberland Road, Kew. Fridays; 6. Kings House, Kings Road, Richmond. (b) Central Reference Library, The Old Town Hall, Whittaker 7. The Lady Eleanor Holies, Hanworth Road, Hampton. Avenue, Richmond, during opening hours; 8. The Mall, Hampton Road, Twickenham. (c) Twickenham Reference Library, Garfield Road, 9. Newland House, Waldegrave Park, Teddington. Twickenham, during opening hours; 10. Old Vicarage, Ellerker Gardens, Richmond. (d) Castelnau Library, 75 Castelnau, Barnes, during opening 11. St. Catherines, Cross Deep, Twickenham. hours; 12. St. Pauls, Lonsdale Road, Barnes. 13. The Swedish School, Lonsdale Road, Barnes. (e) East Sheen Library, Sheen Lane, during opening hours; 14. Tower House, Sheen Lane, East Sheen. (0 Ham Library, Ham Street, Ham, during opening hours; 15. Twickenham, First Cross Road, Twickenham. (g) Hampton Hill Library, Windmill Road, Hampton Hill, 16. Unicorn, Kew Road, Kew. during opening hours; (b) Hampton Library, Rosehill, Hampton, during opening hours; 29th January 1993. (743) (i) Heathfield Library, Percy Road, Whitton, during opening hours; LONDON BOROUGH OF RJCHMOND-UPON-THAMES (j) Kew Library, North Road, Kew, during opening hours; (k) Teddington Library, Waldegrave Road, Teddington, during London Borough ofRichmond-upon-Thames (Waiting and Loading opening hours; Restriction) (Amendment No. -

Sequential Assessment Department for Education

SEQUENTIAL ASSESSMENT DEPARTMENT FOR EDUCATION/BOWMER AND KIRKLAND LAND OFF HOSPITAL BRIDGE ROAD, TWICKENHAM, RICHMOND -UPON- THAMES LALA ND SEQUENTIAL ASSESSMENT On behalf of: Department for Education/Bowmer & Kirkland In respect of: Land off Hospital Bridge Road, Twickenham, Richmond-upon-Thames Date: October 2018 Reference: 3157LO Author: PD DPP Planning 66 Porchester Road London W2 6ET Tel: 0207 706 6290 E-mail [email protected] www.dppukltd.com CARDIFF LEEDS LONDON MANCHESTER NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE ESFA/Bowmer & Kirkland Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 4 2.0 QUANTITATIVE NEEDS ANALYSIS ....................................................... 5 3.0 POLICY CONTEXT .............................................................................11 4.0 SEQUENTIAL TEST METHODOLOGY .................................................17 5.0 ASSESSMENT OF SITES .....................................................................22 6.0 LAND OFF HOSPITAL BRIDGE ROAD ................................................55 7.0 CONCLUSION ...................................................................................57 Land at Hospital Bridge Road, Twickenham, Richmond-upon-Thames 3 ESFA/Bowmer & Kirkland 1.0 Introduction 1.1 This Sequential Assessment has been prepared on behalf of the Department for Education (DfE) and Bowmer & Kirkland, in support of a full planning application for a combined 5FE secondary school and sixth form, three court MUGA and associated sports facilities, together with creation of an area of Public Open Space at Land off Hospital Bridge Road, Twickenham, Richmond-upon- Thames (the ‘Site’). Background 1.2 Turing House School is a 5FE 11-18 secondary school and sixth form, which opened in 2015 with a founding year group (Year 7) on a temporary site on Queens Road, Teddington. The school also expanded onto a further temporary site at Clarendon School in Hampton in September 2018, and plans to remain on both of these temporary sites until September 2020. -

St James's Avenue

CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL LONDON BOROUGH OF RICHMOND UPON THAMES ST JAMES’S AVENUE CONSERVATION AREA NO.82 Consultation Draft, November 2020 Note: Every effort has been made interest. Therefore, the omission of any process a more detailed and up to date to ensure the accuracy of this feature does not necessarily convey assessment of a particular site and its document but due to the complexity a lack of significance. The Council will context is undertaken. This may reveal of conservation areas, it would be continue to assess each development additional considerations relating to impossible to include every facet proposal on its own merits, on a character or appearance which may be ST JAMES’S AVENUE contributing to the area’s special site-specific basis. As part of this of relevance to a particular case. 1 CONSERVATION AREA NO.82 CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL LONDON BOROUGH OF RICHMOND UPON THAMES Introduction PURPOSE OF THIS DOCUMENT The principal aims of conservation • Raise public interest and This document has been area appraisals are to: awareness of the special produced using the guidance set character of their area; out by Historic England in the 2019 • Describe the historic and publication titled Understanding architectural character and • Identify the positive features Place: Conservation Area appearance of the area which should be conserved, Designation, Appraisal and which will assist applicants in as well as negative features Management, Historic England making successful planning which indicate scope for future Advice Note 1 (Second Edition). applications and decision enhancements. makers in assessing planning This document will be a material applications; consideration when assessing planning applications. -

Air Quality Progress Report 2010

London Borough of Richmond upon Thames 2010 Air Quality Progress Report for The London Borough of Richmond upon Thames In fulfillment of Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 Local Air Quality Management Progress Report i London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Local Mr John Coates Authority Officer Department Special Projects Team Address Civic Centre, York Street, Twickenham, TW1 3BZ Telephone 0208 891 7877 e-mail [email protected] Version Updated with ratified data January 2011 Date April 2010 ii Progress Report London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Executive Summary Executive Summary This progress report documents the LBRuT air quality monitoring data over the last eight years, for all the pollutants monitored, namely for nitrogen dioxide (NO2), particulates (PM10), ozone (O3), sulphur dioxide (SO2), carbon monoxide (CO) and benzene (C6H6). The results indicate that both PM10 and NO2 exceeded the air quality objectives. Dependant on weather conditions, some years have been worse than others. Although emission rates may have not varied much, background pollution received from outside the London area sometimes affects levels significantly. In London NO2 levels have been rising, and the reasons for this are being investigated (i.e. the recent (2008) AQEG Report on direct NO2). It therefore remains as important as ever to find ways to reduce emissions so that air pollution levels actually improve. In 2002, the detailed Stage 4 modelling assessment indicated that the objectives would be exceeded, mainly along the major road transport corridors. This was again confirmed by the 2009 USA assessment which identified that: 1) There was a risk of exceeding the objectives for NO2 across the LBRuT.