A Case Study of Antioch College: from Prestige to Closure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Catalog

CURRICULUM CATALOG 2014 – 2016 2 CURRICULUM CATALOG Catalog of Entry Though academic program and graduation requirements of the College may change while a student is enrolled, it is expected that each student will meet the requirements outlined in the catalog that is in effect at the time he or she entered Antioch. The “catalog of entry” is considered applicable for students who leave the College and whose interrupted course of study is not longer than five years. This policy shall come into effect on October 1, 2013, despite the designation of the 2014-2016 edition of the catalog. Catalog Changes The curriculum catalog is a general summary of programs, policies and procedures for academic and student life, and is provided for the guidance of students. However, the catalog is not a complete statement of all programs, policies, and procedures in effect at the College. In addition, the College reserves the right to change without notice any programs, policies and procedures that appear in this catalog. The 2014-2016 edition of the curriculum catalog was published and distributed beginning October 1, 2013. Anyone seeking clarification on any of this information should consult with the registrar. Statement of Non-Discrimination Antioch College is committed to a policy of equal opportunity and non-discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, age, disability, or sexual orientation, as protected by law, in all educational programs and activities, admission of students and conditions of employment. Questions or concerns about this College policy should be directed to the Human Resources Office. Students who have learning disabilities should contact the Office of Academic Support Services. -

2007 Ogde Ut

OMB No 1545-0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947(aXl) of the Internal Revenue Code 2007 (excopt black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 1 Open to Public Department of the Treasu ry Inspection Internal Revenue Service(]]) ► The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting rec irements A For the 2007 calendar year, or tax year beginning NCI `+ i , 2007, and ending EG E I E -fl, aoo-7 B Check if applicable C Employer Identification Number e Address change IRSlabeI NATL CHRISTIAN CHARITABLE FDN, INC. 58-1493949 or print Name change or tee 11625 RAINWATER DRIVE #500 E Telephone number See ALPHARETTA, GA 30004 Initial return specific 404.252.0100 Instruc- Accounting Termination tions. F method: Cash X Accrual Amended return Other (spec ify) ► M Application pending • Section 501 (cx3) organizations and 4947(a)('1 ) nonexempt H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations charitable trusts must attach a completed Schedule A H (a) Is this a group return for affdiates7 Yes No (Form 990 or 990-EZ). H (b) If 'Yes,' enter number of affiliates ► f- WAh cifn • GTG1GT RTDTT0TTATI'T4T?TQTTAAT CflM ► H (e) Are all affiliates included' Yes No F1 (If 'No,' attach a list See instructions ) J Organization ty e (check onl y one) ► X 501(c) 3 4 (insert no) 4947(a)(1) or LI 527 H (d) Is this a separate return filed by an organization covered by a group ruling? F-1 Yes W No K Check here ► [1 if the organization is not a 509(a)(3) supporting organization and its gross receipts are normally not more than $25,000 A return is not required, but if the I Group Exemption Number organization chooses to file a return, be sure to file a complete return M ► Check ► U if the organization is not required to attach Schedule B (Form 990, 990-EZ , or 990- PF) L Gross recei pts Add lines 6b, 8b, 9b, and 10b to line 12 ► 490, 398, 639 . -

A L U M N I M a G a Z I N E 17 24 6 21 30 8 12 10

ANTIOCH 2019 FALL ALUMNI MAGAZINE Creative Minds Using Their AU Education a Better World to Pursue Their AU Creative Minds Using 6 8 10 12 17 21 24 30 Kenny Jude Darby Jessica Markus Mary Lou Leatrice Creative Arts Alexander Bergkamp Bailey Barry Rogan Finley Eiseman Therapies Stand. Together. Live the mission. Take a stand. Win victories for humanity. Since 1852, Antioch has provided the space for ideas to blossom, perspectives to widen, and the pursuit of greater good, but it is the combined voice of our alumni, students, and faculty that has given us our enduring legacy of promoting justice and providing socially engaged learning. We welcome you to continue your Antioch education with our on-campus, online, and low-residency degrees and classes. ANTIOCH.EDU Craig Stockwell ‘90 (New England, Master of Education) began his studies at Dartmouth College and Rhode Island School of Design, where he studied with glass artist Dale Chihuly. He went on to do work in glass in Minneapolis, Boulder, and Boston. His work moved on to conceptually based sculptural installations and was shown in New York, notably at PS 1 (MOMA). In 1998, he made an intentional decision to confine his work to the restrictions of painting as a method of creating a sustainable daily practice. He has shown his drawings and paintings extensively in New England and nationally. His work is in many permanent private and public collections including the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. He earned an MFA degree from Vermont College of Fine Arts and is the Director of the Visual Arts Program at the low-residency MFA at NH Institute for Arts. -

College Fair

Sunday, October 13, 2019 • 1:00 - 3:30 pm COLUMBUS SUBURBAN COLLEGE FAIR helpful hints NEW for a successful LOCATION! college fair Westerville Central High School Pre-Register 7118 Mt. Royal Ave., Westerville, Oh 43082 your profile now to receive information from your college(s) of interest. The Columbus Suburban College Fair sophomores. Each college has a separate 1. Text MASCOT to 75644 and complete your offers you and your family the opportunity table where information is displayed and a profile at the link in the reply text. to explore a variety of colleges and speak representative is available to answer your 2. Colleges will receive your profile directly with admissions representatives. questions. Approximately 200 colleges will information when you select the colleges of your interest This event is a must for all juniors and be arranged alphabetically, And don't and text their 4-digit codes, one by one, to 75644. You most seniors and a great introduction to forget – Financial Aid sessions begin can text more college codes during, and even after, the the college search process for freshmen and at 2:00 p.m. and 3:00 p.m. college fair. Colleges’ 4-digit codes can be found on the college fair website, www.college-fair.org Sponsored by these area Central Ohio High Schools: At the College Fair 1. Introduce yourself to the representative and Bexley Hilliard Davidson St. Francis DeSales Bishop Watterson New Albany Thomas Worthington get his or her name, phone number, and email address. Dublin Coffman Olentangy Upper Arlington This is your contact at that college. -

AUSB Catalog 2014-2015

AUSB Catalog 2014-2015 AUSB Catalog 2014-2015 AUSB Catalog 2014-2015 Table Of Contents Catalog Home ......................................................... 1 General Information .................................................... 2 Accreditation ......................................................... 3 A Message from the President .............................................. 5 The Antioch Story ...................................................... 6 Admissions .......................................................... 11 Undergraduate Program ................................................ 13 Graduate Programs .................................................... 15 International Students .................................................. 17 Transfer Students from Other Antioch Campuses ............................... 19 Readmitted Students ................................................... 20 Admission Decisions ................................................... 21 Deferring Admission ................................................... 22 Financial Aid ........................................................ 23 What Types of Financial Aid Are Available? .................................. 24 Applying for Financial Aid ............................................... 26 Financial Aid Cautions ................................................. 27 Satisfactory Academic Progress (SAP) ....................................... 28 Tuition & Fees ....................................................... 29 Tuition ............................................................ -

Report to the Community 2016

GIVING VOICE WYSO inspires people to tell their stories and makes these stories accessible to all. 2016 - 2017 REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY our community. our nation. our world. TABLE OF CONTENTS GIVING VOICE INTRO | 3 AWARDS | 10 ABOUT WYSO BUDGET NUMBERS | 11 MISSION | 4 WYSO LEADERS | 12-13 LETTER FROM NEENAH | 5 UNDERWRITERS | 14-15 2016-2017 HIGHLIGHTS | 6-7 FOUNDATION SUPPORT | 16 VOLUNTEERS | 8 RESOURCE BOARD | 9 WYSO • 150 East South College Street • Yellow Springs, OH 45387-1607 • Phone: 769.1388 • Fax: 769.1382 • [email protected] WYSO Staff with a special visitors from NPR: Robert Siegel and producer Jess Cheung Our programs give voice to our community. GIVING VOICE Sometimes these are the voices of your neighbors. Sometimes they’re total strangers and you get to walk in their shoes for WYSO inspires people to tell their a moment. stories and makes these stories Sometimes they are the voices that are left out of mainstream media – accessible to all. voices from the periphery. WYSO reaches out to students, veterans, artists, activists, and curious people. Our community. WYSO • 150 East South College Street • Yellow Springs, OH 45387-1607 • Phone: 769.1388 • Fax: 769.1382 • [email protected] our community. our nation. our world. ABOUT US WYSO began with 19 watts of power on February 8, 1958 as a student-run station on the campus of Antioch College. We were on the air four hours a day with an emphasis on local public affairs and music programming. Today we broadcast 24 hours a day, seven days a week with 50,000 watts of power and we reach twelve counties in southwest Ohio with a potential audience of nearly two million listeners. -

Colleges & Universities

Bishop Watterson High School Students Have Been Accepted at These Colleges and Universities Art Institute of Chicago Fordham University Adrian College University of Cincinnati Franciscan University of Steubenville University of Akron Cincinnati Art Institute Franklin and Marshall College University of Alabama The Citadel Franklin University Albion College Claremont McKenna College Furman University Albertus Magnus College Clemson University Gannon University Allegheny College Cleveland Inst. Of Art George Mason University Alma College Cleveland State University George Washington University American Academy of Dramatic Arts Coastal Carolina University Georgetown University American University College of Charleston Georgia Southern University Amherst College University of Colorado at Boulder Georgia Institute of Technology Anderson University (IN) Colorado College University of Georgia Antioch College Colorado State University Gettysburg College Arizona State University Colorado School of Mines Goshen College University of Arizona Columbia College (Chicago) Grinnell College (IA) University of Arkansas Columbia University Hampshire College (MA) Art Academy of Cincinnati Columbus College of Art & Design Hamilton College The Art Institute of California-Hollywood Columbus State Community College Hampton University Ashland University Converse College (SC) Hanover College (IN) Assumption College Cornell University Hamilton College Augustana College Creighton University Harvard University Aurora University University of the Cumberlands Haverford -

Xavier University Newswire

Xavier University Exhibit All Xavier Student Newspapers Xavier Student Newspapers 1961-04-21 Xavier University Newswire Xavier University (Cincinnati, Ohio) Follow this and additional works at: https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/student_newspaper Recommended Citation Xavier University (Cincinnati, Ohio), "Xavier University Newswire" (1961). All Xavier Student Newspapers. 2101. https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/student_newspaper/2101 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Xavier Student Newspapers at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Xavier Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Xavier University Library . .tYR 21 1901 XAVIER. UNIVERSITY NEWS VOLUME XLV CINCINNATI, OHIO, FRIDAY, APRIL 21, 1961 No. 19 Clef Club Season Approaches End; Nancy Hesselbrock Reigns· Dean's Speech Two Toledo Concerts This 'Weekend As Queen Of Jun.ior Prom Finals Wednesday Only four we~ks remain before at the Shertaon~Gibson Hotel on Xavier Unive1·sity's seventh an• the Xavier U~iversity Clef Club Friday, May 12, as part of the nual Dean's Speech Tout·nament brings to a close its 1961 concert season. Under .the direction of Mr. Xavier University Family Day will be held during the week ot April 23. Franklin ·Bens and accompa.nied program. It will . be presented at by Mr. Henri Golembiewski, the .the Sheraton-Gibson Roof Garden Beginning with the semi-final9 singers have had a busy: season in and will be followed by a dance on Monday, April 24, at 11:30 in · the t~o ·months since it opened, which will last until 2:00 a.~. -

Ohio Colleges and University Websites

OHIO COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITY WEBSITES 4-Year Public Universities & Regional Campuses Bowling Green State University www.bgsu.edu BGSU-Firelands www.firelands.bgsu.edu Central State University www.centralstate.edu Cleveland State University www.csuohio.edu Kent State University www.kent.edu Kent State Ashtabula www.ashtabula.kent.edu Kent State East Liverpool www.eliv.kent.edu Kent State Geauga www.geauga.kent.edu Kent State Salem www.salem.kent.edu Kent State Stark www.stark.kent.edu Kent State Trumbull www.trumbull.kent.edu Kent State Tuscarawas www.tusc.kent.edu Miami University www.muohio.edu Miami University Hamilton www.regionals.muohio.edu Miami University Middletown www.regionals.muohio.edu Ohio State University www.osu.edu Ohio State Agricultural Tech. Inst. www.ati.ohio-state.edu Ohio State Lima www.lima.ohio-state.edu Ohio State Mansfield www.mansfield.ohio-state.edu Ohio State Marion www.marion.ohio-state.edu Ohio State Newark www.newark.osu.edu Ohio University www.ohio.edu Ohio University-Eastern Campus www.ohio.edu/eastern Ohio University-Chillicothe Campus www.chillicothe.ohio.edu Ohio University-Lancaster Campus www.ohio.edu/lancaster Ohio University-Southern Campus www.southern.ohio.edu Ohio University-Zanesville Campus www.ohio.edu/ zanesville Shawnee State University www.shawnee.edu The University of Akron www.uakron.edu University of Akron-Wayne www.wayne.uakron.edu University of Cincinnati www.uc.edu University of Cincinnati-Clermont www.clc.uc.edu University of Cincinnati- Raymond Walters www.rwc.uc.edu University -

AU 2021 Fact Sheet

ANTIOCH UNIVERSITY GRANTS AND FOUNDATION RELATIONS FACT SHEET Addresses for Official Correspondence Antioch University Central 900 Dayton Street Midwest Yellow Springs, OH 45387-1745 Graduate School of Leadership and Change Phone: 937-769-1340 Fax: 937-769-1350 Antioch University New England 40 Avon Street New England Keene, NH 03431-3516 Phone: 603-283-2150 Fax: 603-357-0718 Antioch University Los Angeles 400 Corporate Pointe Los Angeles Culver City, CA 90230-7615 Phone: 310-578-1080 Antioch University Seattle 2400 3rd Avenue, Suite 200 Seattle Seattle, WA 98121-4090 Phone: 206-441-5352 Antioch University Santa Barbara 602 Anacapa St. Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA 93101 Phone: 805-962-8179 Private, not for profit Institution of Higher Type of Organization Education 501(c)(3) Non Profit Corporation Federal Congressional Districts & Counties Central/Midwest/ PhD LC OH - 008 Greene County New England NH – 002 Cheshire County Los Angeles CA – 037 Los Angeles County Seattle WA - 007 King County Santa Barbara CA - 024 Santa Barbara County Authorized University Officials for Proposals, Certifications and Assurances William Groves, Chancellor 900 Dayton Street Antioch University Yellow Springs, OH 45387 Graduate School of Leadership and Change 937-769-1340 [email protected] Shawn Fitzgerald, Provost 40 Avon Street New England Keene, NH 03431-3516 603-283-2436 [email protected] AU Fact Sheet 10-2018.doc Allan Gozum, CFO 900 Dayton Street Midwest Yellow Springs, OH 45387 937-769-1304 [email protected] Mark Hower, Provost 400 Corporate Pointe Los Angeles Culver City, CA 90230 310-578-1080 [email protected] Benjamin Pryor, Provost 2400 3rd Avenue, Suite 200 Seattle Seattle, WA 98121 206-441-5352 [email protected] Barbara Lipinski, Provost 602 Anacapa St. -

Antioch University COMMON THREAD

Antioch University COMMON THREAD MARCH 22, 2018 GSLC | STUDENT NAMED INTERIM CHAIRMAN FOR CONSCIOUS CAPITALISM CONNECTICUT AWARDS President and CEO at South Central Connecticut Regional Water Authority, Larry “Bing” Bingaman is the Interim Chairman for Conscious Capitalism Connecticut and announced that the nonprofit association recently received full chapter status from the national organization, joining 25 other Conscious Capitalism chapters across the United States and 14 internationally. Conscious Capitalism believes that business has the capacity to improve society while still making a profit. ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ GSLC | STUDENT’S WORK IMPACTS HIGHER ED INCLUSION Assistant Dean of Community Outreach and Inclusion for the University of Phoenix, Saray E. Lopez is was recently featured in Diverse: Issues in Higher Education magazine for her work to increase outreach to Hispanic students. Read the full article here. ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ GSLC | GSLC STUDENT HONORED FOR STUDENT AFFAIRS VALUES WORK Program Director for the Office of Student Leadership at Temple University, Lauren Bullock was recently awarded the University’s Division of Student Affairs Values Award for Inclusiveness. Additionally, she attended the PA Conference for Women for the third time in five years. The conference focuses on helping women to increase their capacity to lead in business and professional environments and offers an opportunity for women in Pennsylvania to connect and learn with and from each other, as well as becoming better leaders for our businesses and communities. The amazing lineup of global speakers was highlighted by former First Lady Michelle Obama, who served as this year’s featured speaker in an interview by entertainment pioneer Shonda Rhimes. More here. -

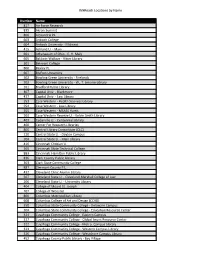

PDF of All Names and Numbers

INNReach Locations by Name Number Name 817 Air Force Research 835 Akron-Summit 800 Alexandria PL 603 Antioch College 604 Antioch University - Midwest 415 Ashland U. - Main 601 Athenaeum of Ohio - E. H. Maly 605 Baldwin-Wallave - Ritter Library 301 Belmont College 800 Bexley PL 607 Blufton University 502 Bowling Green University - Firelands 202 Bowling Green University - W,. T. Jerome Library 261 Bradford Public Library 407 Capital Univ. - Blackmore 427 Capital Univ. - Law Library 553 Case Western - Health Sciences Library 554 Case Western - Law Library 555 Case Western - MSASS Harris 203 Case Western Reserve U. - Kelvin Smith Library 403 Cedarville U. - Centennial Library 400 Center For Research Libraries 800 Central Library Consortium (CLC) 220 Central State U. - Dayton Campus 204 Central State U. - Main Library 416 Cincinnati Chrisian U. 305 Cincinnati State Technical College 883 Cincinnati-Hamilton Public Library 836 Clark County Public Library 303 Clark State Community College 887 Clermont County P.L. 432 Cleveland Clinic Alumni Library 507 Cleveland State U. - Cleveland-Marshall College of Law 206 Cleveland State U. - University Library 404 College of Mount St. Joseph 707 College of Wooster 800 Columbus Metropolitan Library 608 Columbus College of Art and Design (CCAD) 350 Columbus State Community College - Delaware Campus 304 Columbus State Community College - Education Resource Center 324 Cuyahoga Community College - Eastern Campus 327 Cuyahoga Community College - Global Issues Resource Center 322 Cuyahoga Community College - Metro.