Our Kids, Their Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban and Historic Context

Architectural Rejuvenation Project URBAN AND HISTORIC CONTEXT Barry Padolsky Associates Inc., Architects, Urban Design and Heritage Consultants February 13, 2015 Aerial view of National Arts Centre (2010) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction..................................................................................................................................2 Urban and Historic Context........................................................................................................2 . The Holt/Bennett Plan ................................................................................................................4 The Gréber Plan .........................................................................................................................6 The Parkin Plan ...........................................................................................................................8 Architecture and National Identity: the Centennial Projects .......................................................9 NAC: The Architectural Challenge ............................................................................................10 The Architectural Response .....................................................................................................13 Architectural Style: Polite “Brutalism” ......................................................................................16 Re-inventing “Brutalism”..........................................................................................................17 NCC Canada’s -

2015-April.Pdf

2015 April 2/28/2015 SDTCA-3 April, 2015 04/01/2015( ) 3:00PM Brian Hu Asian Films 04/04/2015( ) 9:00AM : Old Coach Trail – Highland Valley Road 14225 Highland Valley Road, Escondido,CA 92025 860-904-3844(Cell) 858-208-5223(Cell) 04/04/2015( ) 1:00PM 04/05/2015( ) 4:00PM Song H. An Technical Performance Review and Discussion on the Biotech Stocks in Our Group Watch List [email protected] 04/11/2015( ) 2:00PM : 04/18/2015( ) 9:00AM : Volcan Mountain at Julian (need carpool) Dudley’s Famous Bakery (30218 Highway 78, Santa Ysabel CA 92070 860- 904-3844(Cell) 858-208-5223(Cell) 04/22/2015( ) 2:15PM : 04/25/2015( ) 2:00PM : Conjoined Twins: A Fascinating Story 05/02/2015( ) 9:00AM : Iron Mountain Trail head parking lot 860-904-3844(Cell) 858-208-5223(Cell) 05/03/2015( ) 4:00PM Long Lee Prediction of Market Trend Added by Technical Analysis [email protected] 02/28/2015( ) 5:30PM TAFSD/TACC 03/14/2015( ) 2:00PM : SDTCA-4 April, 2015 2015 4 15 -1 2015 15 -0 $30 (SDTCA) 15 -0 858-603-0135, [email protected] $120 $60 ( ) $140 $70 ( ) $10 $20 $30 ( ) 858-444-7164 [email protected]. Rosa Ken Fu / SDTCA-5 April, 2015 Kenneth Fu 228 228 228 228 Kenneth Tonya Tonya / slideshow 2014 SDTCA-6 check out DVD April, 2015 handout - Nissan Toyota Prius (2008) Leaf 1. $40000 2. 10,000 rebates 3. 5 cents per mile. Nissan overall 4. 1980 carpool El Cajon 5. / 440V 220V 10 miles highway < 65mph 110V < 40mph 3 miles 6. -

Community Profile for LOWER TOWN, OTTAWA, ON

Community Profile for LOWER TOWN, OTTAWA, ON LEGEND A child’s early development is shaped by different sectors of influence: Map WHAT DOES OUR COMMUNITY LOOK LIKE? DEMOGRAPHICS AGE DISTRIBUTION CHILD FAMILY COMMUNITY Demographics L. Town Ottawa Population in 2011 12,183 883,391 19+ Years 0 to 6 years Why are Population Demographics Important? 4% Population in 2006 11,377 812,129 Collectively, population counts by age group and population growth can 90% 10% 3% 7 to 12 years Population change (%) 7.1% 8.8% help us to adapt to the needs of the population as it changes over time. 3% 13 to 18 years Population density measures how closely people live together in a Land area (square km) 2.1 2,790 geographic area. The higher the number, the more people live within Population per km2 5,918 317 that area. Park area (square km) 0.08 43.1 Population Counts L. Town Ottawa 2 Total 12,180 882,355 Why are Park Areas Important? Population per km 146,024 20,500 Aged 0 to 18 yrs 1,240 193,795 Source: 2011 Census, Population and Dwelling Counts. Green spaces, like park areas, can enhance the community’s well-being Aged 0 to 6 yrs 500 68,440 in several areas: social, recreational, environmental, physical and Source: 2011 Census, Age Characteristics. mental health, educational and economic. They filter pollutants and dust from the air, they provide shade and lower temperatures in urban CRIME RATES AND CIVIC ENGAGEMENT areas, and they even reduce erosion of soil into our waterways. -

Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers Stephen D. Feeley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Stephen D., "Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623324. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4nn0-c987 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers Volume I Stephen Delbert Feeley Norcross, Georgia B.A., Davidson College, 1996 M.A., The College of William and Mary, 2000 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. APPROVAL SHEET This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Stephen Delbert F eele^ -^ Approved by the Committee, January 2007 MIL James Axtell, Chair Daniel K. Richter McNeil Center for Early American Studies 11 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Members 1909 (PDF)

THE ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF CANADA Officers for 1909 Honorary President—W. F. K i n g , C.M.G., LL.D., Chief Astronomer, Ottawa. President—W . B a l f o u r M u s s o n . First Vice-President—Professor A l f r e d T. D e L u r y . Second Vice-President—Professor Louis B. S t e w a r t . Secretary—J. R. C o l l i n s . Treasurer—C h a s . P. S p a r l i n g , Recorder—Miss E lsie A. Dent. Librarian—A. S i n c l a i r , M.A. Curator—R o b e r t S. D u n c a n . Council—The above Officers and the following members :— J o s e p h P o p e , C.M.G., Ottawa; A. F. M i l l e r , Toronto; Rev. I. J. K a v a n a g h , S.J., Montreal; R. S t e w a r t M u i r , Toronto ; D r . A. D. W a t s o n , Toronto; J. S. P l a s k e t t , B.A., Ottawa; and Past Presidents A n d r e w E l v i n s , J o h n A. P a t e r s o n , K.C., M.A., R. F. S t u p a r t , F.R.S.C., Professor C. A. C h a n t ; and the presiding officer at each Centre as follows : D r . -

Table 5 Number of WITB Recipients and Amount Credited by Federal Electoral District, 2017 Table 5 Number of WITB Recipients

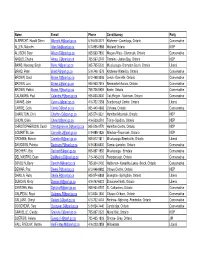

Table 5 Number of WITB recipients and amount credited by Federal Electoral District, 2017 Assessed WITB Federal Electoral District Number of WITB Credit Recipients ($ dollars) Abbotsford 4,500 3,486,000 Abitibi--Baie-James--Nunavik--Eeyou 3,490 2,603,000 Abitibi--Témiscamingue 2,490 1,885,000 Acadie--Bathurst 3,050 2,136,000 Ahuntsic-Cartierville 5,720 4,838,000 Ajax 6,060 5,296,000 Alfred-Pellan 3,800 3,288,000 Algoma--Manitoulin--Kapuskasing 2,620 1,994,000 Argenteuil--La Petite-Nation 3,830 3,225,000 Aurora--Oak Ridges--Richmond Hill 5,450 4,925,000 Avalon 2,220 1,624,000 Avignon--La Mitis--Matane--Matapédia 1,890 1,359,000 Banff--Airdrie 4,950 3,765,000 Barrie--Innisfil 4,990 4,188,000 Barrie--Springwater--Oro-Medonte 4,590 3,666,000 Battle River--Crowfoot 4,450 3,520,000 Battlefords--Lloydminster 2,680 2,107,000 Bay of Quinte 4,240 3,244,000 Beaches--East York 5,240 4,286,000 Beauce 2,610 2,135,000 Beauport--Côte-de-Beaupré--Île d’Orléans--Charlevoix 2,140 1,774,000 Beauport--Limoilou 3,280 2,651,000 Beauséjour 2,680 2,000,000 Bellechasse--Les Etchemins--Lévis 2,710 2,185,000 Beloeil--Chambly 2,960 2,466,000 Berthier--Maskinongé 3,410 2,764,000 Bonavista--Burin--Trinity 2,070 1,457,000 Bourassa 6,410 5,345,000 Bow River 4,480 3,643,000 (Continued) Notes: 1. All counts are rounded to the nearest ten and all amounts are rounded to the nearest thousand. -

R:\Facility Management\Seating Plans\2021\2021.02.15\CAD Dwgs

Legislative Assembly of Ontario Seating Plan MPPs and various House officers sit in the legislative chamber when the House is in session. The Speaker’s dais is at one end of the chamber, and the main doors are at the opposite end of the chamber. The Speaker sits facing the main doors. The government sits on the right side of the Speaker in four rows. The opposition sits on the left side of the Speaker in three rows. The first row is closest to the centre of the chamber. The seats in each row are ordered from the Speaker’s dais to the main doors. Speaker and other House officers The Speaker of the House sits at one end of the chamber. Above the Speaker’s dais is the press gallery. To the right of the Speaker’s dais are two seats designated for legislative counsel. One is assigned to M. Spakowski; the second is unassigned. In front of the Speaker, in the middle of the chamber, is the clerks’ table. The Clerks-at-the-Table include Todd Decker, Trevor Day, Tonia Grannum, William Short, Valerie Quioc Lim, and Meghan Stenson. Beyond the clerks’ table is the Hansard table with two seats for Hansard reporters. Beyond the Hansard table, just before the main doors, sits the Sergeant-at-Arms, Jackie Gordon. Above the Sergeant-at-Arms is the Speaker’s gallery. Government side, row 1: Hon. Jeff Yurek Elgin—Middlesex—London Minister of the Environment, Conservation and Parks Hon. Stephen Lecce King—Vaughan Minister of Education Hon. Caroline Mulroney York—Simcoe Minister of Transportation; Minister of Francophone Affairs Hon. -

Grid Export Data

Public Registry of Designated Travellers In accordance with the Members By-law, a Member of the House of Commons may designate one person, other than the Member’s employee or another Member who is not the Member’s spouse, as their designated traveller. The Clerk of the House of Commons maintains the Public Registry of Designated Travellers. This list discloses each Member’s designated traveller. If a Member chooses not to have a designated traveller, that Member’s name does not appear on the Public Registry of Designated Travellers. The Registry may include former Members as it also contains the names of Members whose expenditures are reported in the Members’ Expenditures Report for the current fiscal year if they ceased to be a Member on or after April 1, 2015 (the start of the current fiscal year). Members are able to change their designated traveller once every 365 days, at the beginning of a new Parliament, or if the designated traveller dies. The Public Registry of Designated Travellers is updated on a quarterly basis. Registre public des voyageurs désignés Conformément au Règlement administratif relatif aux députés, un député de la Chambre des communes peut désigner une personne comme voyageur désigné sauf ses employés ou un député dont il n’est pas le conjoint. La greffière de la Chambre des communes tient le Registre public des voyageurs désignés. Cette liste indique le nom du voyageur désigné de chaque député. Si un député préfère ne pas avoir de voyageur désigné, le nom du député ne figurera pas dans le Registre public des voyageurs désignés. -

Ottawa Centre

Sick of living without enough income? Tired of being in need of affordable housing? In this federal election, Poverty and Housing Matter! Vote for the candidate in the Party that speaks to your concerns! Conservative Party Green Party Liberal Party New Democratic Party Ottawa www.conservative.ca www.greenparty.ca www.liberal.ca (NDP) www.ndp.ca Centre Leader: Stephen Harper Leader: Elizabeth May Leader: Justin Trudeau Leader: Tom Mulcair Candidate: Candidate: Candidate: Candidate: Paul Dewar Riding Damian Konstantinakos Tom Milroy Catherine McKenna Where do Parties *Increase the allowable *Create a National *Renew federal leadership *Prioritize affordable stand on tax free withdrawals from Housing Strategy that in affordable housing. housing and homelessness Affordable RRSP accounts by $10,000 would provide permanent across Canada. (Home Buyers’ Plan) *Help build more housing Housing? housing and supports. *Take concrete action in units, refurbish existing *Commit to federal coordination with ones, renew existing co- government being a “long *Make private developers provinces to curb foreign operative agreements, and term stable partner in speculation in Canada’s include a percentage of provide operational funding building affordable residential real estate affordable housing in their support for municipalities. housing”. market housing projects. Where do Parties *Introduce National stand on *In 2007, Conservatives *Establish a Guaranteed *Create new National Poverty Elimination Act, a Poverty introduced Workers Livable Income, to ensure Child Benefit that would federal plan to eliminate Reduction? Income Tax Benefit: no Canadian falls below an combine family tax and poverty with affordable federal refundable tax credit income level needed to live transfers, with higher housing, affordable that boosts the earned with dignity. -

MP-Email and Phone List.Xlsm

Name E-mail Phone Constituency Party ALBRECHT, Harold Glenn [email protected] 519-578-3777 Kitchener--Conestoga, Ontario Conservative ALLEN, Malcolm [email protected] 613-995-0988 Welland Ontario NDP ALLISON, Dean [email protected] 905-563-7900 Niagara West--Glanbrook, Ontario Conservative ANGUS, Charlie [email protected] 705-567-2747 Timmins--James Bay, Ontario NDP BAINS, Navdeep Singh [email protected] 905-795-5220 Mississauga--Brampton South, Ontario Liberal BRAID, Peter [email protected] 519-746-1573 Kitchener-Waterloo, Ontario Conservative BROWN, Gord [email protected] 613-498-3096 Leeds--Grenville, Ontario Conservative BROWN, Lois [email protected] 905-953-7515 Newmarket-Aurora, Ontario Conservative BROWN, Patrick [email protected] 705-726-5959 Barrie, Ontario Conservative CALANDRA, Paul [email protected] 905-833-3030 Oak Ridges - Markham, Ontario Conservative CANNIS, John [email protected] 416-752-2358 Scarborough Centre, Ontario Liberal CARRIE, Colin [email protected] 905-440-4868 Oshawa, Ontario Conservative CHARLTON, Chris [email protected] 905-574-3331 Hamilton Mountain, Ontario NDP CHOW, Olivia [email protected] 416-533-2710 Trinity--Spadina, Ontario NDP CHRISTOPHERSON, David [email protected] 905-526-0770 Hamilton Centre, Ontario NDP COMARTIN, Joe [email protected] 519-988-1826 Windsor--Tecumseh, Ontario NDP CROMBIE, Bonnie [email protected] 905-812-1811 Mississauga-Streetsville, Ontario Liberal DAVIDSON, Patricia [email protected] 519-383-6600 Sarnia--Lambton, Ontario Conservative -

2018 Election Liberal Party of Ontario Candidates

2018 Election Liberal Party of Ontario Candidates NAME RIDING WEBSITE LINK Joe Dickson Ajax [email protected] Naheed Yaqubian Aurora-Oak Ridges- [email protected] Richmond Hill Ann Hoggarth Barrie-Innisfil [email protected] Robert Quaiff Bay of Quinte [email protected] Arthur Potts Beaches-East York [email protected] Safdar Hussain Brampton Centre [email protected] Dr. Parminder Singh Brampton East [email protected] Harinder Malhi Brampton North [email protected] Sukhwant Thethi Brampton South [email protected] Vic Dhillon Brampton West [email protected] Ruby Toor Brantford-Brant [email protected] Francesca Dobbyn Bruce-Grey-Owen Sound [email protected] Eleanor McMahon Burlington [email protected] Kathryn McGarry Cambridge [email protected] Theresa Qadri Carleton [email protected] Margaret Schleier Stahl Chatham-Kent-Leamington [email protected] Cristina Martins Davenport [email protected] Michael Coteau Don Valley East [email protected] Shelley Carroll Don Valley North [email protected] Kathleen Wynne Don Valley West [email protected] Bob Gordanier Dufferin-Caledon [email protected] Granville Anderson Durham [email protected] 1 | P a g e NAME RIDING WEBSITE LINK Mike Colle Eglinton-Lawrence [email protected] Carlie Forsythe -

Obituary by Carolyn Quinn

Heritage Ottawa NEWSLETTER Dedicated to Preserving Our Built Heritage Fall 2003 Volume 30, No. 3 President’s Report by David B. Flemming Buildings at Risk The demolition of the Caplan building has entered its second month and the last portions of the Rideau Street facade are coming down slowly so as not to rain bricks upon pedestrians on the street below. With the demolition of the Caplan building, Ottawa has lost one of the best examples of its 19th century commercial architecture. The next preservation battle will be the one to save the former Registry Office on Nicholas Street. Built in 1873, it is a designated heritage building owned by Viking-Rideau Corporation who have recently said that the building has no part in their proposed expansion This interesting mural for more than a decade, graced the west wall of the Bowles Lunch of Rideau Centre and the Congress Building on Sparks Street facing the site once occupied by the Citizen Building and the place Centre. A few years ago, Viking-Rideau where D’Arcy Mc Gee was assassinated. The vacant lot was latterly used by individual offered to move the building to another orators to deliver their messages to passers-by, and so acquired the name Speakers’ Corner location and it is hoped that if we after that part of Hyde Park, London,U.K., which has for a much longer period served a cannot change their minds about similar purpose, though on a grander scale. preserving it on-site, they will still agree Heritage Ottawa supported the mixed-use development of this site, with the facade to a move.