Cumbria and Lancashire Network for Collaborative Outreach (CLNCO) January 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College Employer Satisfaction League Table

COLLEGE EMPLOYER SATISFACTION LEAGUE TABLE The figures on this table are taken from the FE Choices employer satisfaction survey taken between 2016 and 2017, published on October 13. The government says “the scores calculated for each college or training organisation enable comparisons about their performance to be made against other colleges and training organisations of the same organisation type”. Link to source data: http://bit.ly/2grX8hA * There was not enough data to award a score Employer Employer Satisfaction Employer Satisfaction COLLEGE Satisfaction COLLEGE COLLEGE responses % responses % responses % CITY COLLEGE PLYMOUTH 196 99.5SUSSEX DOWNS COLLEGE 79 88.5 SANDWELL COLLEGE 15678.5 BOLTON COLLEGE 165 99.4NEWHAM COLLEGE 16088.4BRIDGWATER COLLEGE 20678.4 EAST SURREY COLLEGE 123 99.2SALFORD CITY COLLEGE6888.2WAKEFIELD COLLEGE 78 78.4 GLOUCESTERSHIRE COLLEGE 205 99.0CITY COLLEGE BRIGHTON AND HOVE 15088.0CENTRAL BEDFORDSHIRE COLLEGE6178.3 NORTHBROOK COLLEGE SUSSEX 176 98.9NORTHAMPTON COLLEGE 17287.8HEREFORDSHIRE AND LUDLOW COLLEGE112 77.8 ABINGDON AND WITNEY COLLEGE 147 98.6RICHMOND UPON THAMES COLLEGE5087.8LINCOLN COLLEGE211 77.7 EXETER COLLEGE 201 98.5CHESTERFIELD COLLEGE 20687.7WEST NOTTINGHAMSHIRE COLLEGE242 77.4 SOUTH GLOUCESTERSHIRE AND STROUD COLLEGE 215 98.1ACCRINGTON AND ROSSENDALE COLLEGE 14987.6BOSTON COLLEGE 61 77.0 TYNE METROPOLITAN COLLEGE 144 97.9NEW COLLEGE DURHAM 22387.5BURY COLLEGE121 76.9 LAKES COLLEGE WEST CUMBRIA 172 97.7SUNDERLAND COLLEGE 11487.5STRATFORD-UPON-AVON COLLEGE5376.9 SWINDON COLLEGE 172 97.7SOUTH -

Leading Wellbeing Retreat in Indonesia in February

Abstracts, Keywords and Biographies RESEARCH F LEADESINTIGVA WL ELLBEING 20 15 Twitter Feed Hashtag: #leadingwell Access wifi with the following code: brathaywifiaccess Who are Brathay Trust and the University of Cumbria? Brathay Trust At Brathay we know that everyone has the capacity to do extraordinary things that can inspire and benefit others. This drives our mission to improve the life chances of children, young people and families by inspiring them to engage positively in their communities. We support our charitable eforts through enterprising fundraising and events, together with the knowledge in our research hub, and complimentary professional activity that delivers organisational and people development consultancy to private and public sector organisations. Contents Our dynamic approach is built upon a mutual trust that reaches out to touch communities across the UK from our inspiring Lake District base. Our expert teams engage with people of all ages and from all walks of life to discover the Brathay efect, Page 3 to 5 enthused by a simple belief in the transformational power of people working together. Who are Brathay Trust and the University of Cumbria? People and Organisational Development at Brathay – from Page 6 to 11 inspirational individuals to inspiring people At a glance Paper Sessions In 1968, a management development consultant called John Adair found his way to Brathay Hall and experimented with his ideas, developed at Sandhurst Military Academy, Page 12 to 22 with commercial clients. Brathay was able to observe and learn from John, who was to take his Action Centred Leadership model to a global audience. At the same time, Paper Session 1: Thursday 17:00 to 18:00 apprentice managers who had seen the impact Brathay had on their young employees, asked Brathay to work with more senior staf, developing their leadership and team Page 23 to 37 working skills to enhance business efectiveness. -

Brathay Trust

BRATHAY TRUST CHILD PROTECTION AND SAFEGUARDING POLICY & PROCEDURES [INCLUDING SAFEGUARDING VULNERABLE ADULTS] DESIGNATED CHILD PROTECTION OFFICER: GODFREY OWEN, CHIEF EXECUTIVE CONTACT DETAILS: MOBILE PHONE: 07739 646144 EMAIL: [email protected] 1 DOCUMENT MANAGEMENT RECORD CHILD PROTECTION POLICY & SAFEGUARDING PROCEDURES (REPLACES PREVIOUS SAFEGUARDING POLICY, DATED Dec. 2011) Originated: November 2011 Next Full Document Review Date: March 2017 Document Status Issue Date Notes Originator Authorised by: 1 January 2011 Draft Document issued for Leadership Team Jon Owen n/a consultation 2. February 2011 Document issued to Trustees for review and Godfrey J. Burdon-Bailey signed off in principle Owen (Chair) 3. February 2011 Document issued to Management Group for Jon Owen Godfrey Owen review 4. March 2011 Document issued to Leadership Team for final Jon Owen Godfrey Owen sign-off 5. 21 April 2011 CEO sign-off; Document distributed to staff via Jon Owen Godfrey Owen email 6. 23 November Two new draft sections added: Child Sexual Jon Owen n/a 2011 Exploitation & Use of Reasonable Force; Draft issued for Leadership Team consultation 7. 12 December New policy signed off by Leadership Team and Jon Owen Godfrey Owen 2011 Mgmnt Group; distributed to staff via email 8. December Policy review commenced by Director of Young Dale Godfrey Owen 2013 People Services Tomlinson 9. February 2014 Policy review completed. Policy reviewed by Godfrey Owen CEO and circulated to Management Group for review 10. March 2014 Management review completed and final Godfrey Owen version circulated to entire organisation 11 March 2014 Policy circulated to Trustees Godfrey Owen 12 February 2015 Edits made: double waking night cover, Dave Godfrey Owen overnight supervision at venues, instant Harvey messaging guidelines, staff recruitment sections 13 November Incorporated Lone Working policy & procedure Godfrey Godfrey Owen 2015 into a procedure of main policy and placed as Owen appendix. -

Outcomes from IQER: 2010-11 the Student Voice

Outcomes from IQER: 2010-11 The student voice July 2012 Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................... 1 Summary ................................................................................................................................ 2 Student engagement: context ................................................................................................. 3 Themes .................................................................................................................................. 6 Theme 1: Student submissions for the IQER reviews ......................................................... 6 Theme 2: Student representation in college management: extent of student representation, specific student-focused committees and contact with senior staff ............. 7 Theme 3: How colleges gather and use student feedback information ................................ 8 The themes in context ............................................................................................................ 9 Conclusions .......................................................................................................................... 10 Areas of strength as indicated by the evidence from the reports ....................................... 10 Areas where further work is required ................................................................................ 11 Appendix A: Good practice relating to student engagement ................................................ -

Trip Notes: Lake District Rock and Roll, 3

Trip notes: Lake District rock and roll, 3 - 5 November 2017 Many thanks for joining us for what I’m sure will be an awesome weekend. While we need to be flexible, the plan is to ride from our accommodation on Saturday – lowish level but awesome riding with some great techie sections. Weather permitting, we’ll use the mini bus to get a day in the mountains on Sunday – maybe Nan Bield, Helvellyn or High Street, or possibly a little lower but equally as exhilarating, above Coniston. We’ll have a full briefing over dinner on Friday evening and probably again on Saturday! Our accommodation We’re staying in Shackleton Lodge on the Brathay Estate, just outside Ambleside – details below. It’s a huge place with a large lounge and plenty of rooms. The beds are mainly bunks in large rooms and we won’t need to have more than 2 to a room. Remember to bring a sleeping bag, pillow and towel. We can get access to the lodge from 5pm on Friday evening and we aim dinner for 8pm on the first night, to give folk time to arrive. We’ll have breakfast together before heading out on Saturday and Sunday and enjoy more of Jo’s wonderful cooking for dinner on Saturday. Lunch arrangements will remain reasonably flexible to fit in with the day’s riding. Getting there: Satnav postcode is LA22 0HP. From the south, exit the M6 at junction 36 and merge onto the A590 (signposted Barrow A590 and Windermere, Kendal A591). Follow the A591 to Ambleside. -

Framework Users (Clients)

TC622 – NORTH WEST CONSTRUCTION HUB MEDIUM VALUE FRAMEWORK (2019 to 2023) Framework Users (Clients) Prospective Framework users are as follows: Local Authorities - Cheshire - Cheshire East Council - Cheshire West and Chester Council - Halton Borough Council - Warrington Borough Council; Cumbria - Allerdale Borough Council - Copeland Borough Council - Barrow in Furness Borough Council - Carlisle City Council - Cumbria County Council - Eden District Council - South Lakeland District Council; Greater Manchester - Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council - Bury Metropolitan Borough Council - Manchester City Council – Oldham Metropolitan Borough Council - Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council - Salford City Council – Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council - Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council - Trafford Metropolitan Borough - Wigan Metropolitan Borough Council; Lancashire - Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council – Blackpool Borough Council - Burnley Borough Council - Chorley Borough Council - Fylde Borough Council – Hyndburn Borough Council - Lancashire County Council - Lancaster City Council - Pendle Borough Council – Preston City Council - Ribble Valley Borough Council - Rossendale Borough Council - South Ribble Borough Council - West Lancashire Borough Council - Wyre Borough Council; Merseyside - Knowsley Metropolitan Borough Council - Liverpool City Council - Sefton Council - St Helens Metropolitan Borough Council - Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council; Police Authorities - Cumbria Police Authority - Lancashire Police Authority - Merseyside -

North West Introduction the North West Has an Area of Around 14,100 Km2 and a Population of Almost 6.9 Million

North West Introduction The North West has an area of around 14,100 km2 and a population of almost 6.9 million. The metropolitan areas of Greater Manchester and Merseyside are the most significant centres of population; other major urban areas include Liverpool, Blackpool, Blackburn, Preston, Chester and Carlisle. The population density is 490 people per km2, making the North West the most densely populated region outside London. This population is largely concentrated in the southern half of the region; Cumbria in the north has just 24 people per km2. The economy The economic output of the North West is almost £119 billion, which represents 13 per cent of the total UK gross value added (GVA), the third largest of the nine English regions. The region is very varied economically: most of its wealth is created in the heavily populated southern areas. The unemployment rate stood at 7.5 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2010, compared with the UK rate of 7.9 per cent. The North West made the highest contribution to the UK’s manufacturing industry GVA, 13 per cent of the total in 2008. It was responsible for 39 per cent of the UK’s GVA from the manufacture of coke, refined petroleum products and nuclear fuel, and 21 per cent of UK manufacture of chemicals, chemical products and man-made fibres. It is also one of the main contributors to food products, beverages, tobacco and transport equipment manufacture. Gross disposable household income (GDHI) of North West residents was one of the lowest in the country, at £13,800 per head. -

Regional Profiles North-West 29 ● Cumbria Institute of the Arts Carlisle College__▲■✚ University of Northumbria at Newcastle (Carlisle Campus)

North-West Introduction The North-West has an area of around 14,000 km2 and a population of over 6.3 million. The metropolitan area of Greater Manchester is by far the most significant centre of population, with 2.5 million people in the city and its wider conurbation. Other major urban areas are Liverpool, Blackpool, Blackburn, Preston, Chester and Carlisle. The population density is 477 people per km2, making the North-West the most densely populated region outside London. However, the population is largely concentrated in the southern half of the region. Cumbria, by contrast, has the third lowest population density of any English county. Economic development The economic output of the North-West is around £78 billion, which is 10 per cent of the total UK GDP. The region is very varied economically, with most of its wealth created in the heavily populated southern areas. Important manufacturing sectors for employment and wealth creation are chemicals, textiles and vehicle engineering. Unemployment in the region is 5.9 per cent, compared with the UK average of 5.4 per cent. There is considerable divergence in economic prosperity within the region. Cheshire has an above average GDP, while Merseyside ranks as one of the poorest areas in the UK. The total income of higher education institutions in the region is around £1,400 million per year. Higher education provision There are 15 higher education institutions in the North-West: eight universities and seven higher education colleges. An additional 42 further education colleges provide higher education courses. There are almost 177,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) students in higher education in the region. -

South Lakeland District Council Cabinet 9 April 2014

South Lakeland District Council Cabinet 9th April 2014 South Lakeland District Council Royal Wedding Fund-Future Options PORTFOLIO: Councillor Graham Vincent – Health and Wellbeing Portfolio Holder REPORT FROM: Shelagh McGregor - Assistant Director (Resources) and Chief Finance Officer REPORT AUTHOR: Matthew Neal - Solicitor to the Council WARDS: not applicable KEY DECISION NO: not applicable 1.0 EXPECTED OUTCOME 1.1 The purpose of this report is to seek approval from Cabinet to wind up the South Lakeland District Council Fund originally set up in Commemoration of the Wedding of His Royal Highness Prince Charles to Lady Diana Spencer (“the Trust”) and to pass the Trust fund to 3 other organisations with similar purposes as set out in the report. 1.2 A consequential amendment to the constitution would enable Audit Committee to take an oversight role in terms of ensuring that the money is spent for the appropriate purposes RECOMMENDATION Cabinet is recommended to give approval to the following: (1) The winding up of the South Lakeland District Council Fund in Commemoration of the Wedding of His Royal Highness Prince Charles to Lady Diana Spencer (“the Trust”); and (2) The assets of the Trust be passed to three charities in the following proportions: (a) One-sixth of the assets of the Trust to the Leeds Children’s Holiday Camp Association (otherwise known as the Leeds Children’s Charity); (b) One third of the assets of the Trust to Bendrigg Trust ; and (c) Half of the assets of the Trust to Brathay Trust; and (3) The Assistant Director (Resources) and Chief Finance Officer be authorised to take all necessary steps to give effect to the winding up of the Trust and (4) Full Council be recommended to approve that the Audit Committee’s terms of reference be extended to include, under the heading of Audit Activity, monitoring the expenditure of funds transferred from the Trust to the above charities. -

PROSPECTUS Full-Time Courses & Apprenticeships 2019 - 2020

PROSPECTUS Full-Time Courses & Apprenticeships 2019 - 2020 www.kendal.ac.uk T: 01539 814700 E: [email protected] @kendalcollege Contents Welcome to STUDYING AT KENDAL COLLEGE Welcome to Kendal College ........................... 3 Kendal College Creating Bright Futures ........................................ 4 What our former students say ....................... 5 State-of-the-Art Facilities .......................................6-7 I am delighted that you are thinking about coming to Kendal College Dedicated Study Spaces & for the next phase of your education. Progression Centre .................................................. 8 Student Life ................................................................... 9 We are a modern and forward-thinking Our superb facilities are matched by our Opportunities to Consider ...........................10-11 college offering a variety of qualifications, team of staff. You will be taught by experts Understanding Levels ...........................................12 and just by considering Kendal College as a who are highly qualified, professional and Careers Advice ..........................................................13 place to study you have already taken the friendly, and are passionate about their Visit Us .............................................................................14 first step towards a bright future. We have subject and teaching. Applying to College ..............................................15 a lot to offer, so I am sure you will find a Kendal College is a fantastic -

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

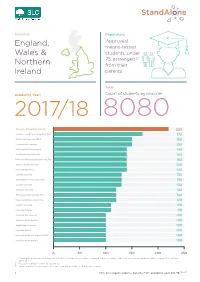

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill -

People Achieveto

® inspiring young people achieveto Annual Review 2014-2015 Including the Annual Report and Financial Statements THE DUKE OF EDINBURGH’S AWARD Contents Overview .................................................................... 3 Thank you to all our supporters .................................. 4 Our Licensed Organisation partners ............................ 6 Chairman’s Report .................................................... 10 Our strategic objectives ............................................ 12 Supporting DofE delivery .......................................... 13 Extending the reach .................................................. 13 Driving achievement ................................................. 13 Fuelling growth ......................................................... 15 Financial performance .............................................. 16 Funding the DofE ...................................................... 18 Trustees’ commitment .............................................. 19 Thank you ................................................................ 19 Independent Auditors’ Report ................................... 20 Statutory accounts ................................................... 22 Appendices .............................................................. 42 Trustees .................................................................... 49 The Trustees present their report and the financial statements of the Royal Charter Corporation for the year ended 31 March 2015. In preparing this report the