Return to Cooper's Creek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks

Department for Environment and Heritage Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks Part of the Far North & Far West Region (Region 13) Historical Research Pty Ltd Adelaide in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd Lyn Leader-Elliott Iris Iwanicki December 2002 Frontispiece Woolshed, Cordillo Downs Station (SHP:009) The Birdsville & Strzelecki Tracks Heritage Survey was financed by the South Australian Government (through the State Heritage Fund) and the Commonwealth of Australia (through the Australian Heritage Commission). It was carried out by heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd, in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd, Lyn Leader-Elliott and Iris Iwanicki between April 2001 and December 2002. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia and they do not accept responsibility for any advice or information in relation to this material. All recommendations are the opinions of the heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd (or their subconsultants) and may not necessarily be acted upon by the State Heritage Authority or the Australian Heritage Commission. Information presented in this document may be copied for non-commercial purposes including for personal or educational uses. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires written permission from the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia. Requests and enquiries should be addressed to either the Manager, Heritage Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001, or email [email protected], or the Manager, Copyright Services, Info Access, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601, or email [email protected]. -

Innamincka Regional Reserve About

<iframe src="https://www.googletagmanager.com/ns.html?id=GTM-5L9VKK" height="0" width="0" style="display:none;visibility:hidden"></iframe> Innamincka Regional Reserve About Check the latest Desert Parks Bulletin (https://cdn.environment.sa.gov.au/parks/docs/desert-parks-bulletin- 21092021.pdf) before visiting this park. Innamincka Regional Reserve is a park of contrasts. Covering more than 1.3 million hectares of land, ranging from the life-giving wetlands of the Cooper Creek system to the stark arid outback, the reserve also sustains a large commercial beef cattle enterprise, and oil and gas fields. The heritage-listed Innamincka Regional Reserve park headquarters and interpretation centre gives an insight into the natural history of the area, Aboriginal people, European settlement and Australia's most famous explorers, Burke and Wills. From the interpretation centre, visit the sites where Burke and Wills died, and the historic Dig Tree site (QLD) which once played a significant part in their ill-fated expedition. Shaded by the gums, the waterholes provide a relaxing place for a spot of fishing or explore the creek further by canoe or boat. Opening hours Open daily. Fire safety and information Listen to your local area radio station (https://www.cfs.sa.gov.au/public/download.jsp?id=104478) for the latest updates and information on fire safety. Check the CFS website (https://www.cfs.sa.gov.au/site/home.jsp) or call the CFS Bushfire Information Hotline 1800 362 361 for: Information on fire bans and current fire danger ratings (https://www.cfs.sa.gov.au/site/bans_and_ratings.jsp) Current CFS warnings and incidents (https://www.cfs.sa.gov.au/site/warnings_and_incidents.jsp) Information on what to do in the event of a fire (https://www.cfs.sa.gov.au/site/prepare_for_a_fire.jsp) Please refer to the latest Desert Parks Bulletin (https://cdn.environment.sa.gov.au/parks/docs/desert-parks-bulletin- 21092021.pdf) for current access and road condition information. -

A Review of Lake Frome & Strzelecki Regional Reserves 1991-2001

A Review of Lake Frome and Strzelecki Regional Reserves 1991 – 2001 s & ark W P il l d a l i f n e o i t a N South Australia A Review of Lake Frome and Strzelecki Regional Reserves 1991 – 2001 Strzelecki Regional Reserves Lake Frome This review has been prepared and adopted in pursuance to section 34A of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972. Published by the Department for Environment and Heritage Adelaide, South Australia July 2002 © Department for Environment and Heritage ISBN: 0 7590 1038 2 Prepared by Outback Region National Parks & Wildlife SA Department for Environment and Heritage Front cover photographs: Lake Frome coastline, Lake Frome Regional Reserve, supplied by R Playfair and reproduced with permission. Montecollina Bore, Strzelecki Regional Reserve, supplied by C. Crafter and reproduced with permission. Department for Environment and Heritage TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................................................iii LIST OF TABLES..................................................................................................................................................iii LIST OF ACRONYMS and ABBREVIATIONS...................................................................................................iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ......................................................................................................................................iv FOREWORD .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Vol No Artist Title Date Medium Comments 1 Acraman, William

Tregenza PRG 1336 SOUTH AUSTRALIAN HISTORICAL PICTURES INDEX ARTIST INDEX (Series 1) (Information taken from photo - some spellings may be incorrect) Vol No Artist Title Date Medium Comments 1 Acraman, William Residence of E Castle Esq re Hackham Morphett Vale 1856 Pencil 1 Adamson, James Hazel Early South Australian view 1 Adamson, James Hazel Lady Augusta & Eureka Capt Cadell's first vessels on Murray 1853 Lithograph 1 Adamson, James Hazel The Goolwa 1853 Lithograph 1 Adamson, James Hazel Agricultural show at Frome Road 1853 W/c 1 Adamson, James Hazel Jetty at Port Noarlunga with Yatala in background 1855 W/c 1 Adamson, James Hazel Panorama of Goolwa from water showing Steamer Lady Augusta 1854 Pencil & wash No photo 1 Angas, George French SA Illustrated photocopies of plates List in front 1 Angas, George French Portraits (2) 1 Angas, George French Devil's Punch Bowl 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Encounter Bay looking south 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Interior of crater, Mount Shanck 1844 W/c Plus current 1 Angas, George French Lake Albert 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Mt Lofty from Rapid Bay W/c 1 Angas, George French Interior of Principal Crater Mt Gambier - evening 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Penguin Island near Rivoli Bay 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Port Adelaide 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French Port Lincoln from Winter's Hill 1845 W/c 1 Angas, George French Scene of the Coorong at the Narrows 1844 W/c 1 Angas, George French The Goolwa - evening W/c 1 Angas, George French Sea mouth of the Murray 1844-45 W/c 1 Angas, -

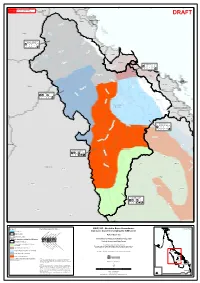

GWQ1203 - Burdekin Basin Groundwater Location Map Watercourse Cainozoic Deposits Overlying the GAB Zones

144°0'0"E 145°0'0"E 146°0'0"E 147°0'0"E 148°0'0"E 149°0'0"E Tully 18°0'0"S This map must not be used for marine navigation. 18°0'0"S Comprehensive and updated navigation WARNING information should be obtained from published Mitchell hydrographic charts. Murray DRAFT Hinchinbrook Island Herbert r ve Ri ekin urd B Ingham ! er iv D R ry Gilbert ry Ri D v er r e iv 19°0'0"S Scattered Remnants Northern R 19°0'0"S g Burdekin Headwaters in n n R u Black Townsville ! er r iv e R v rke i la R C r ta S Ross Broken River Ayr ! er ver Riv i ry lt R Haughton go Basa e r Don and Bogie Coastal Area G h t r u ve o i ton R S h ug Ha Bowen ! 20°0'0"S 20°0'0"S r Charters Towers e v ! i Don R B n o o g i D e Riv er Bur dek in R ive r Whitsunday Island Proserpine B owe Proserpine Flinders n ! er R Riv iver e sp a R amp C o Don River l l s to n R iv C e a r North West Suttor Catchment pe R r iv ve e i r R r o t t u S r e Broken v R i iv S e R e r llh L e e i O'Connell p im t t a l R e C iv er B o w e B u r d ekin n B u r d ekin R 21°0'0"S i 21°0'0"S v e BB a a s s in in r B ro Mackay ke ! n River Pioneer Plane Sarina ! Eastern Weathered Su ttor R Cainozoic Remnants Belyandor River iv e er iv R o d n lya e B r e v i R o d Moranbah n ! a ly 22°0'0"S e 22°0'0"S l R B ae iver ich Carm r ive R Diamantina s r o n n o C Styx Belyando River Saline Tertiary Sediments Dysart ! Is a a c R iv B Clermont Middlemount er e ! ! l y an do Riv e r er iv Cooper Creek R ie nz Aramac e ! k c a M 23°0'0"S 23°0'0"S Capella -

Innamincka Regional Reserve Draft Management Plan 2017

Innamincka Regional Reserve Draft Management Plan 2017 Recognising the cultural and interconnected nature of Innamincka Regional Reserve, and working together towards sustainable land use Your views are important A management plan for the Innamincka Regional Reserve is being prepared to ensure the long term protection of the regional reserve’s natural values and advance spiritual, cultural, social and economic opportunities for the traditional custodians – the Yandruwandha people and the Yawarrawarrka people. The Innamincka Regional Reserve Draft Management Plan is now released for public consultation. Members of the community are encouraged to express their views on the future management of this regional reserve. A final plan will be prepared in response to submissions received on this draft plan. Once prepared, the final plan will be forwarded to the Minister for Sustainability, Environment and Conservation for consideration, together with a detailed analysis of submissions received. Notice of the adoption of the final plan will be published in the Government Gazette and the final Innamincka Regional Reserve Management Plan will be made available at: www.environment.sa.gov.au/parkmanagement. I encourage you to make a submission on this draft plan. John Schutz Director of National Parks and Wildlife Cultural Sensitivity Warning Aboriginal people are warned that this publication may contain culturally sensitive material. 1 Developing this draft plan This draft management plan was developed by the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources (DEWNR) with advice from the Yandruwandha Yawarrawarrka Parks Advisory Committee. It draws on feedback received in response to a stakeholder workshop and a discussion paper that was released to the public in 2015. -

Innamincka/Cooper Creek State Heritage Area Innamincka/Cooper Creek Was Declared a State Heritage Area on 16 May 1985

Innamincka/Cooper Creek State Heritage Area Innamincka/Cooper Creek was declared a State Heritage Area on 16 May 1985. HISTORY Innamincka and Cooper Creek have a rich history. The area has also been associated with many other facets of the state's history since colonial settlement. Names such as Charles Sturt, Sidney Kidman, Cordillo Downs, the Australian Inland Mission and the Reverend John Flynn are intrinsically woven into the stories of Innamincka and the Cooper Creek. Its significance for Aboriginal people spans thousands of years as a trade route and a source of abundant food and fresh water. The area's Aboriginal history also includes significant contacts with explorers, pastoralists and settlers. Many sources believe that the name 'Innamincka' comes from two Aboriginal words meaning ' your shelter' or 'your home'. European contact with the region came first with the explorers and later with the establishment of the pastoral industry, transport routes and service centres. Cooper Creek was named by Captain Charles Sturt on 13 October 1845, when he crossed the watercourse at a point approximately 24 kilometres west of the current Innamincka township. The water was very low at the time, hence his use of the term 'creek' rather than 'river' to describe what often becomes a deep torrent of water. Charles Cooper, after whom the waterway was named, was a South Australian judge - later Chief Justice Sir Charles Cooper. On the same expedition, Sturt also named the Strzelecki Desert after the eccentric Polish explorer, Paul Edmund de Strzelecki, who was the first European to climb and name Mount Kosciusko. -

Narrative of an Expedition Into Central Australia Performed Under the Authority of Her Majesty's Government During the Years 1844, 5, and 6

Narrative of an Expedition into Central Australia Performed under the Authority of Her Majesty's Government during the Years 1844, 5, and 6 Together with a Notice of the Province of South Australia in 1847 Sturt, Charles (1795-1869) A digital text sponsored by William and Sarah Nelson University of Sydney Library Sydney 2001 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/ozlit/ © University of Sydney Library. The texts and Images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: Prepared from the print edition published by T. and W. Boone, 29, New Bond Street. London 1849 All quotation marks retained as data All unambiguous end-of-line hyphens have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line. First Published: 1849 Languages: F5202 Australian Etexts 1840-1869 exploration and explorers (land) prose nonfiction 2001 Creagh Cole Coordinator Final Checking and Parsing Narrative of an Expedition into Central Australia Performed under the Authority of Her Majesty's Government during the Years 1844, 5, and 6. Together with a Notice of the Province of South Australia in 1847 By F.L.S. F.R.G.S. etc. etc. Author of “Two Expeditions Into Southern Australia” London T. and W. Boone, 29, New Bond Street. 1849 To The Right Honorable The Earl Grey, ETC. ETC. ETC. MY LORD, ALTHOUGH the services recorded in the following pages, which your Lordship permits me to dedicate to you, have not resulted in the discovery of any country immediately available for the purposes of colonization, I would yet venture to hope that they have not been fruitlessly undertaken, but that, as on the occasion of my voyage down the Murray River, they will be the precursors of future advantage to my country and to the Australian colonies. -

Grs 513/11/P

GPO Box 464 Adelaide SA 5001 Tel (+61 8) 8204 8791 Fax (+61 8) 8260 6133 DX:336 [email protected] www.archives.sa.gov.au Special List GRS 513 Lodged company documents of defunct companies Series These files contain documents lodged by companies in Description accordance with the varying Companies Acts. Company files may contain some or all of the following lodged documents: Memorandum of Agreement, Articles of Association, Certificate of Incorporation, lists of shareholders, lists of directors, special resolutions ie. issues of shares, underwriting agreements and annual returns. Note: The term 'defunct' should not be understood to refer to the company. In this context it refers to the file being defunct, although given the age of the records some of the companies will have become defunct. Series date range 1844 - 1986 Agency State Records of South Australia responsible Access Open. Determination Contents 1874 – 1935 1 June 2016 GRS 513/11/P DEFUNCT COMPANIES FILES 4/1S74 The Stonyfell Olive Company Limited (Scm) \ 4/1874 The Stonyfell Olive Co. Limited (1 file) 1/1875 The East End Market Company (16cm)) 1/1S75 The East End Market Coy. Ltd. (1 file) 3/1SSO The Executor Trust & Agency Company of South Australia Limited (9cm &9cm)(2 bundles)) 10/1S7S Adelaide Underwriters Association Limited (3cm) 10/1S7S Marine Underwriters Association of South Australia Limited (1 file) 20/1SS2 Elder's Wool and Produce Company Limited (Scm) 4/1SS2 Northern Territory Laud Company Limited (4cm) 3/1SSO Executor Trustee & Agency Company of South Australia (Scm) 3/1SSO Executor Trustee & Agency Company of South Australia Limited (1 file) 7/1SS2 Northern Territory Land Company (1 file) 20/1SS2 Elder Smith & Co. -

2018 September Quarter

Hancock Agriculture September 2018 3, Issue 3 Hancock Kidman Making us the best Cattle Company National Agriculture and Related Industries Day National Agriculture and Related Industries Day will be held again this year on Wednesday 21 November 2018. To all pastoral properties and employees you should start thinking of how we can all start celebrating this important day. Santa Gertrudis and Coolibah Composite bulls in forage oats on Rockybank Staon Inside this issue Naonal Agriculture and Related Industries Day ................1 Wed, 21 November 2018 Message from Your Chairman .....2 Sydney CBD Speech by Mrs Gina Rinehart Reserve your tables or seats AmCham 50th Anniversary Gala now for the annual gala dinner Dinner .........................................4 (Akubras and boots welcome!) [email protected] Message from Your CEO ..............10 Capex / Opex upgrades ...............11 General Manager Updates ..........12 Health and Wellbeing Mental Health Month..................14 Staon News ...............................15 Done Training Courses ................16 Future Important Dates Staff Achievements Hancock Agriculture 2019 recruitment ad ...........................17 Santa Gertrudis cale at S. Kidman & Co Pty Ltd Naryilco Staon, Qld Message from Your Chairman Dear team members I hope you are all doing well and I appreciate the wonderful efforts and commitment that you are making including through the drought – rain is, together with you all, the key to life on staons and farms too. We should see a moratorium on all government fees and charges for at least two years to allow people to recover on the land. Of course this is not the first me I have called for red tape and taxes to be reduced, for instance I refer to this in my speech to AmCham in the newsleer, and why this has been so successful in the USA, as making people more able to get on with business and get out of debt, is much beer than loans which push people further into debt, with interest and me consuming reporng obligaons. -

100 the SOUTH-WEST CORNER of QUEENSLAND. (By S

100 THE SOUTH-WEST CORNER OF QUEENSLAND. (By S. E. PEARSON). (Read at a meeting of the Historical Society of Queensland, August 27, 1937). On a clear day, looking westward across the channels of the Mulligan River from the gravelly tableland behind Annandale Homestead, in south western Queensland, one may discern a long low line of drift-top sandhills. Round more than half the skyline the rim of earth may be likened to the ocean. There is no break in any part of the horizon; not a landmark, not a tree. Should anyone chance to stand on those gravelly rises when the sun was peeping above the eastem skyline they would witness a scene that would carry the mind at once to the far-flung horizons of the Sahara. In the sunrise that western region is overhung by rose-tinted haze, and in the valleys lie the purple shadows that are peculiar to the waste places of the earth. Those naked, drift- top sanddunes beyond the Mulligan mark the limit of human occupation. Washed crimson by the rising sun they are set Kke gleaming fangs in the desert's jaws. The Explorers. The first white men to penetrate that line of sand- dunes, in south-western Queensland, were Captain Charles Sturt and his party, in September, 1845. They had crossed the stony country that lies between the Cooper and the Diamantina—afterwards known as Sturt's Stony Desert; and afterwards, by the way, occupied in 1880, as fair cattle-grazing country, by the Broad brothers of Sydney (Andrew and James) under the run name of Goyder's Lagoon—and the ex plorers actually crossed the latter watercourse with out knowing it to be a river, for in that vicinity Sturt describes it as "a great earthy plain." For forty miles one meets with black, sundried soil and dismal wilted polygonum bushes in a dry season, and forty miles of hock-deep mud, water, and flowering swamp-plants in a wet one. -

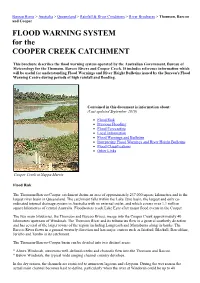

FLOOD WARNING SYSTEM for the COOPER CREEK CATCHMENT

Bureau Home > Australia > Queensland > Rainfall & River Conditions > River Brochures > Thomson, Barcoo and Cooper FLOOD WARNING SYSTEM for the COOPER CREEK CATCHMENT This brochure describes the flood warning system operated by the Australian Government, Bureau of Meteorology for the Thomson, Barcoo Rivers and Cooper Creek. It includes reference information which will be useful for understanding Flood Warnings and River Height Bulletins issued by the Bureau's Flood Warning Centre during periods of high rainfall and flooding. Contained in this document is information about: (Last updated September 2019) Flood Risk Previous Flooding Flood Forecasting Local Information Flood Warnings and Bulletins Interpreting Flood Warnings and River Height Bulletins Flood Classifications Other Links Cooper Creek at Nappa Merrie Flood Risk The Thomson-Barcoo-Cooper catchment drains an area of approximately 237,000 square kilometres and is the largest river basin in Queensland. The catchment falls within the Lake Eyre basin, the largest and only co- ordinated internal drainage system in Australia with no external outlet, and which covers over 1.1 million square kilometres of central Australia. Floodwaters reach Lake Eyre after major flood events in the Cooper. The two main tributaries, the Thomson and Barcoo Rivers, merge into the Cooper Creek approximately 40 kilometres upstream of Windorah. The Thomson River and its tributaries flow in a general southerly direction and has several of the larger towns of the region including Longreach and Muttaburra along its banks. The Barcoo River flows in a general westerly direction and has major centres such as Isisford, Blackall, Barcaldine, Jericho and Tambo in its catchment. The Thomson-Barcoo-Cooper basin can be divided into two distinct areas: * Above Windorah, numerous well-defined creeks and channels flow into the Thomson and Barcoo.