Transforming Development Knowledge Volume 51 | Number 2 | September 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Becoming a Feminist Architect, … Visible, Momentous, With

1 ISSN: 1755-068 www.field-journal.org vol.7 (1) Becoming a Feminist Architect, … visible, momentous, with Karin Reisinger and Meike Schalk 1 Besides this issue, the conference has led This issue is one of three publications subsequent to the 13th International to Hélène Frichot, Catharina Gabrielsson Architectural Humanities Research Association (AHRA) Conference and Helen Runting, eds., Architectures “Architecture & Feminisms: Ecologies, Economies, Technologies,” which and Feminisms: Ecologies, Economies, th Technologies (London: Routledge, was held at KTH School of Architecture, Stockholm, between the 17 to 2017) and Karin Reisinger and Meike 19th November in 2016.1 The conference gathered around 200 participants Schalk, eds., “Styles of Queer Feminist and included over a hundred paper presentations and performances, Practices and Objects,” Architecture and Culture Vo. 5 Issue 3 (2017). as well as two exhibitions. The overwhelming interest in reviving the feminist discourse in architecture gave us the opportunity to reflect on the 2 Elizabeth Grosz, ed., Becomings: process of becoming feminist architects. Becoming a feminist architect Explorations in Time, Memory, and is a complex process, rife with strategies, tactics, frictions, advances and Futures (Ithaca and London: Cornell retreats, that will continue to engage us in the future as it does now. University Press,1999), 77-157. This became clear through the presentations of a wide range of different 3 Doina Petrescu. “Foreword: From feminist architectural practices, both historical and contemporary, Alterities and Beyond,” in Altering their diverse theoretical underpinnings and methodological reflections Practices: Feminist Politics and Poetics and speculations. The present publication assembles a series of vital of Space, ed. Doina Petrescu (London and New York: Routledge, 2007), xvii. -

1. AC Michael, Christian Activist for Human Rights

Endorsed by - (In alphabetical order) 1. A C Michael, Christian Activist For Human Rights And Former Member Delhi Minorities Commission 2. A. Hasan, Retired Banker 3. A. K Singh, NA 4. A. Reyna Shruti, Student 5. A. Giridhar Rao, NA 6. A. M. Roshan, Concerned Citizen 7. A. Selvaraj, Former Chief Commissioner Of Income Tax 8. Aakanksha, Student 9. Aakash Gautam, NA 10. Aakshi Sinha, NA 11. Aastha, Student/Teacher 12. Abde Mannaan Yusuf, Moderator IAD 13. Abdul Ghaffar, Manager, Private Firm 14. Abdul Kalam, NA 15. Abdul Mabood, Citizen 16. Abdul Wahab, Social Activist / Business 17. Abha Choudhuri, Homemaker And Caregiver 18. Abha Dev Habib, Assistant Professor, Miranda House, DU 19. Abha Rani Devi, NA 20. Abha, Research Scholar 21. Abhay Kardeguddi, CEO 22. Abhay, Lawyer 23. Abhijit Kundu, Faculty, DU 24. Abhijit Sinha, Mediaman 25. Abhinandan Sinha, NA 26. Achin Chakraborty, NA 27. Achla Sawhney, NA 28. Adithi, Teacher 29. Aditi Mehta, IAS Retd. 30. Aditya Mukherjee, Professor 31. Aditya Nigam, Academic, Delhi 32. Admiral L Ramdas, Former Chief Of Naval Staff 33. Adnan Jamal, Student 34. Adv. Ansar Indori, Human Rights Lawyer 35. Afaq Ullah, Social Worker 36. Aftab, Advocate 37. Agrima, Student 38. Ahmar Raza, Retired Scientist 39. Aiman Khan, Researcher 40. Aiman Siddiqui, Journalist 41. Aishah Kotecha, Principal 42. Aishwarya Bajpai, Student 43. Aishwarya, NA 44. Ajay Singh Mehta, NA 45. Ajay Skaria, Professor, History And Global Studies, University Of Minnesota 46. Ajay T G, Filmmaker 47. Ajin K Thomas, Researcher, Ahmedabad 48. Ajmal V, Freelance Journalist 49. Akash Bhatnagar, IT 50. Akha, NA 51. -

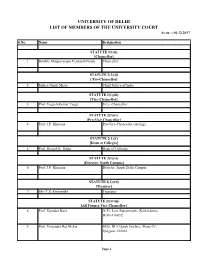

UNIVERSITY of DELHI LIST of MEMBERS of the UNIVERSITY COURT As on :- 04.12.2017

UNIVERSITY OF DELHI LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE UNIVERSITY COURT As on :- 04.12.2017 S.No. Name Designation STATUTE 2(1)(i) [Chancellor] 1 Hon'ble Muppavarapu Venkaiah Naidu Chancellor STATUTE 2(1)(ii) [ Pro-Chancellor] 2 Justice Dipak Misra Chief Justice of India STATUTE 2(1)(iii) [Vice-Chancellor] 3 Prof. Yogesh Kumar Tyagi Vice -Chancellor STATUTE 2(1)(iv) [Pro-Vice-Chancellor] 4 Prof. J.P. Khurana Pro-Vice-Chancellor (Acting) STATUTE 2(1)(v) [Dean of Colleges] 5 Prof. Devesh K. Sinha Dean of Colleges STATUTE 2(1)(vi) [Director, South Campus] 6 Prof. J.P. Khurana Director, South Delhi Campus STATUTE 2(1)(vii) [Tresurer] 7 Shri T.S. Kripanidhi Treasurer STATUTE 2(1)(viii) [All Former Vice-Chancellor] 8 Prof. Upendra Baxi A-51, Law Appartments, Karkardoma, Delhi-110092 9 Prof. Vrajendra Raj Mehta 5928, DLF Qutab Enclave, Phase-IV, Gurgaon-122002 Page 1 10 Prof. Deepak Nayyar 5-B, Friends Colony (West), New Delhi-110065 11 Prof. Deepak Pental Q.No. 7, Ty.V-B, South Campus, New Delhi-110021 12 Prof. Dinesh Singh 32, Chhatra Marg, University of Delhi, Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(ix) [Librarian] 13 Dr. D.V. Singh Librarian STATUTE 2(1)(x) [Proctor] 14 Prof. Neeta Sehgal Proctor (Offtg.) STATUTE 2(1)(xi) [Dean Student's Welfare] 15 Prof. Rajesh Tondon Dean Student's Welfare STATUTE 2(1)(xii) [Head of Departments] 16 Prof. Christel Rashmi Devadawson The Head Department of English University of Delhi Delhi-110007 17 Prof. Sharda Sharma The Head Department of Sanskrit University of Delhi Delhi-110007 18 Prof. -

DEPARTMENT of POLITICAL SCIENCE 2019-20.Docx

DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE The Department of Political Science has actively and substantively organized a gamut of academic events and programmes throughout the session of 2019-20. On 20th August 2019, the functioning of La Politique, the association of the department, commenced with the orientation programme arranged particularly for the 1st year students of the department. On September 2, 2019, democratically elected Union of the department was formed, with Heena Makwana and Pankaj Yadav elected as the President and Vice President respectively. General Secretary Surabhi Das along with the worthy Joint Secretaries and Executive Council members further glorified the team. On 20th September 2019, La Politique organized an official Fresher’s Welcomeprogramme with a view to promote interaction and bonding among all the students of the department. On 18th October 2019, La Politique in collaboration with North East Students' Cell of Kirori Mal College organized a panel discussion on National Register of Citizens (NRC) and Citizenship Rights. Two eminent penalists, namely, Ms. Sangeeta BarooahPisharoty, Deputy Editor, The Wire and Prof. Apoorvanand, Professor of Hindi, University of Delhi delivered an engaging and enriching session. Enthusiastic participation of students with their inquisitive interventions and critical questioning marked the success of the event. The fresh week of January 2020 witnessed a remarkable session on "The USA and West Asia: Global Implications”. Prof. Sanjeev Kumar HM of University of Delhi was the keynote speaker who delivered an insightful and thought- provoking lecture on the theme. The session was followed by book launch of the book titled “Global Politics”writtenbyDr. RupakDattagupta. La Politique also promoted and facilitated in-house discussion among the students of the department offering them an exposure to democratic culture of debate and deliberation. -

A Reflection on NEP 2020

ISSN: 2456-9550 JMC November 2020 ACADEMIC FREEDOM, INSTITUTIONAL AUTONOMY AND INSTITUTIONALISING ACCOUNTABILITY: A REFLECTION ON THE NATIONAL EDUCATION POLICY 2020 SAUMEN CHATTOPADHYAY Email: [email protected] Zakir Husain Centre for Educational Studies, School of Social Sciences Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Volume 4, 2020 THE JMC REVIEW An Interdisciplinary Social Science Journal of Criticism, Practice and Theory http://www.jmc.ac.in/the-jmc-review/content/ JESUS AND MARY COLLEGE UNIVERSITY OF DELHI NEW DELHI-110021 The JMC Review, Vol. IV 2020 ACADEMIC FREEDOM, INSTITUTIONAL AUTONOMY AND INSTITUTIONALISING ACCOUNTABILITY: A REFLECTION ON THE NATIONAL EDUCATION POLICY 2020 SAUMEN CHATTOPADHYAY Abstract A series of reforms have been mooted in the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 to rejuvenate the Indian higher education system. It appears that overhauling of the entire structure of regulatory intervention is crucially dependent on giving autonomy to the students, teachers and universities. An examination of the NEP through the lens of the faculty would reveal how the role and performance of the professoriate have been assessed in the overall diagnosis of the challenges facing the Indian higher education system. This paper discusses the concept of autonomy of the teachers as well as of the university and how the issue of institutionalisation of accountability has been dealt in the NEP. This paper critically examines two fundamental policy recommendations, one, the proposal to raise public funding to 6 per cent of GDP for the education sector as a whole and two, to curb commercialisation and encourage philanthropy in higher education. The way entire architecture of regulatory intervention has been designed, it seems that a quasi-market for higher education is to be constructed to foster competitiveness both within the higher education institution and within the higher education system. -

Violence and Discrimination Against India's Religious Minorities

briefing A Narrowing Space: Violence and discrimination against India's religious minorities Center for Study of Society and Secularism & Minority Rights Group International Friday prayer at the Jama Masjid, New Delhi. Mays Al-Juboori. Acknowledgements events. Through these interventions we seek to shape public This report has been produced with the assistance of the opinion and influence policies in favor of stigmatized groups. Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. In recognition of its contribution to communal harmony, CSSS The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of was awarded the Communal Harmony award given by the Minority Rights Group International and the Center for Study Ministry of Home Affairs in 2015. of Society and Secularism, and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Swedish International Development Minority Rights Group International Cooperation Agency. Minority Rights Group International (MRG) is a non-governmental organization (NGO) working to secure the rights of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and indigenous peoples worldwide, and to promote cooperation and understanding between communities. Our activities are focused on international advocacy, training, publishing and outreach. We are guided by the needs expressed by our worldwide partner network of organizations, which represent Center for Study of Society and Secularism minority and indigenous peoples. The Centre for Study of Society and Secularism (CSSS) is a non profit organization founded in 1993 by the celebrated MRG works with over 150 organizations in nearly 50 Islamic scholar Dr. Asghar Ali Engineer. CSSS works in countries. Our governing Council, which meets twice a different states of India. CSSS works for the rights of the year, has members from 10 different countries. -

Parlour: the First Five Years

143 ISSN: 1755-068 www.field-journal.org vol.7 (1) Parlour: The First Five Years Naomi Stead, Gill Matthewson, Justine Clark, and Karen Burns Parlour: women, equity, architecture is a group whose name derives from a rather subversive feminist take on the 'parlour' as the room in a house traditionally used for receiving and conversing with visitors. In its first five years, Parlour has grown from a scholarly research project into an activist group with an international reach, but a localised approach to working through issues of equity and diversity in architecture. This paper is a lightly edited version of a keynote 'lecture' given jointly by four of the key members of the Parlour collective. 144 www.field-journal.org vol.7 (1) Some readers may be familiar with the work of the activist group Parlour: 1 Please note that the order of women, equity, architecture.1 Some might even know the origins of our authors’ names are listed by the name: a rather subversive feminist take on the ‘parlour’ as the room in a order in which we spoke – as house traditionally used for receiving and conversing with visitors. The opposed to a hierarchical account of importance or contribution. name itself derives from the French parler – to speak – hence, a space to speak. But even if you knew these things, you might not realize that what has become an internationally recognized activist organization, working towards greater gender equity in the architecture profession, began its existence as a scholarly research project. This paper is a lightly edited version of a keynote ‘lecture’ given jointly by four of the key members of the Parlour collective. -

Annual Report 2016-17 SAS

Annual Report 2017 Honourable guests, members of the college community and my dear students, I heartily welcome you all to the College Annual Day, the Day for which you have really worked hard, right from your academic scores to sports events, from NCC parades to NSS camps, from Departmental societies to the Arts & Culture Society. Well, the day has arrived and we all are here with our distinguished guest and invited dignitaries to appreciate your efforts. It is a pleasure to introduce the chief guest for the day, Prof. J.P.Khurana – Pro-Vice-Chancellor, University of Delhi. Prof. Jitendra P. Khurana is the Pro-Vice-Chancellor of Delhi University. As Head of the Plant and Molecular Biology Department, he was an avid believer in the ability to convert knowledge into practical application for the welfare of human beings. He specializes in Photoperception and Signal Transduction Mechanisms in plants; Plant Hormone Action Mechanisms; Structural and Functional Genomics in Plants. A recipient of the prestigious the Professor Birbal Sahni Medal by the Indian Botanical Society in the year 2011, the Professor Panchanan Maheshwari Memorial Lecture Award by the Indian National Science Academy in the year 2008; and the Prof. Shri Ranjan Memorial Award by the National Academy of Sciences, India in the year 2006; his research Interests and contributions to the field are noteworthy. He was awarded the ‘Tata Innovation Fellowship’ by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India from 2010 to 2013. With over a 150 publications to his credit; his research group has contributed extensively to the area of light perception and signal transduction mechanisms in plants. -

Over 500 Academicians, Activists, Artists and Writers Including Eminent Professors Noam Chomsky, Gayatri Spivak, Barbara Hariss

Over 500 academicians, activists, artists and writers including eminent Professors Noam Chomsky, Gayatri Spivak, Barbara Hariss-White, Michael Davis among others condemn the ongoing state violence and unlawful detention of faculty and student protesters of the University of Hyderabad. We, academicians, activists, artists and writers, condemn the ongoing brutal attacks on and unlawful detention of peacefully protesting faculty and students at the University of Hyderabad by the University administration and the police. We also condemn the restriction of access to basic necessities such as water and food on campus. The students and faculty members of the University of Hyderabad were protesting the reinstatement of Dr. Appa Rao Podile as the Vice-Chancellor despite the ongoing judicial enquiry against him related to the circumstances leading to the death of the dalit student Rohith Vemula on January 17th, 2016. Students and faculty members of the university community are concerned that this may provide him the opportunity to tamper with evidence and to influence witnesses. Suicides by dalit students have been recurring in the University of Hyderabad and other campuses across the country. The issue spiraled into a nationwide students’ protest with the death of the dalit scholar Rohith Vemula. The protests have pushed into the foreground public discussion and debate on the persistence of caste-based discrimination in educational institutions, and surveillance and suppression of dissent and intellectual debate in university spaces. Since the morning of March 22 when Dr. Appa Rao returned to campus, the students and staff have been in a siege-like situation. The peacefully protesting staff and students were brutally lathi-charged by the police, and 27 people were taken into custody. -

Mapping the (Invisible) Salaried Woman Architect: the Australian Parlour Research Project Karen Burns, Justine Clark and Julie Willis

143 Review Article Mapping the (Invisible) Salaried Woman Architect: The Australian Parlour Research Project Karen Burns, Justine Clark and Julie Willis The (invisible) salaried woman architect: The architects in the service of bureaucracies. This Parlour project special journal issue retrieves a domain of ‘invis- During the 1970s, feminist historians highlighted ible’ architects, and our paper offers a distinctive ‘women’s invisibility’ in written histories and argued focus on the topic by exploring the gendering of the that these absences exposed structural biases in salaried architect. We begin by drawing attention to history writing.1 Through mainstream history and its the over-representation of women as salaried archi- privileging of particular topics and institutional struc- tects in both the historical record and contemporary tures, history’s very objects of inquiry threatened practice. Moving beyond this demographic outline, to perpetuate women’s invisibility. For example, the paper studies women architects’ everyday work although women had been political participants in the office.5 Focusing the gaze of historians and throughout history, they had organised and oper- theorists on the office rather than the building site ated in informal ways and their practices were provides an important shift of attention that chal- marginalised within the historical record.2 For some lenges them to conceptualise the production of historians, it was not simply a task of adding women buildings within the organisation of the architectural in and -

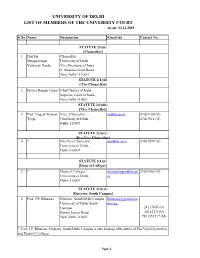

UNIVERSITY of DELHI LIST of MEMBERS of the UNIVERSITY COURT As On: 12.11.2018

UNIVERSITY OF DELHI LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE UNIVERSITY COURT As on: 12.11.2018 S.No Name Designation Email ids Contact No. STATUTE 2(1)(i) [Chancellor] 1 Hon'ble Chancellor Muppavarapu University of Delhi Venkaiah Naidu Vice-President of India 6, Maulana Azad Road, New Delhi - 110011 STATUTE 2(1)(ii) [ Pro-Chancellor] 2 Justice Ranjan Gogoi Chief Justice of India Supreme Court of India New Delhi-110001 STATUTE 2(1)(iii) [Vice-Chancellor] 3 Prof. Yogesh Kumar Vice -Chancellor [email protected] 27001100 (O) Tyagi University of Delhi, 27667011 (O) Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(iv) [Pro-Vice-Chancellor] 4 * Pro-Vice-Chancellor [email protected] 27667899 (O) University of Delhi, Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(v) [Dean of Colleges] 5 * Dean of Colleges [email protected]. 27667066 (O) University of Delhi, in Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(vi) [Director, South Campus] 6 Prof. J.P. Khurana Director, South Delhi Campus khuranaj@genomein University of Delhi South dia.org Campus 24117005 (O) Benito Jaurez Road 24112231(O) New Delhi-110021 9811351217 (M) * Prof. J.P. Khurana, Director, South Delhi Campus is also looking after duties of Pro-Vice-Chancellor and Dean of Colleges Page 1 STATUTE 2(1)(vii) [Tresurer] 7 Shri T.S. Kripanidhi Treasurer kripanidhits@yahoo. 9818928162 University of Delhi co.in Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(viii) [All Former Vice-Chancellor] 8 Prof. Upendra Baxi A-51, Law Appartments, [email protected] 8447944106 (M) Karkardoma, n Delhi-110092 baxiupendra@gmail. 9 Prof. Vrajendra Raj 5928, DLF Qutab Enclave, 9350292197 (M) Mehta Phase-IV, Gurgaon-122002 10 Prof. -

The Politics of Friends in Modern Architecture, 1949-1987”

Title: “The politics of friends in modern architecture, 1949-1987” Name of candidate: Igea Santina Troiani, B. Arch, B. Built Env. Supervisor: Professor Jennifer Taylor This thesis was submitted as part of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Design, Queensland University of Technology in 2005 i Key words Architecture - modern architecture; History – modern architectural history, 1949-1987; Architects - Alison Smithson, Peter Smithson, Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi, Elia Zenghelis, Rem Koolhaas, Philosophy - Jacques Derrida, Politics of friendship; Subversive collaboration ii Abstract This thesis aims to reveal paradigms associated with the operation of Western architectural oligarchies. The research is an examination into “how” dominant architectural institutions and their figureheads are undermined through the subversive collaboration of younger, unrecognised architects. By appropriating theories found in Jacques Derrida’s writings in philosophy, the thesis interprets the evolution of post World War II polemical architectural thinking as a series of political friendships. In order to provide evidence, the thesis involves the rewriting of a portion of modern architectural history, 1949-1987. Modern architectural history is rewritten as a series of three friendship partnerships which have been selected because of their subversive reaction to their respective establishments. They are English architects, Alison Smithson and Peter Smithson; South African born architect and planner, Denise Scott Brown and North American architect, Robert Venturi; and Greek architect, Elia Zenghelis and Dutch architect, Rem Koolhaas. Crucial to the undermining of their respective enemies is the friends’ collaboration on subversive projects. These projects are built, unbuilt and literary. Warring publicly through the writing of seminal texts is a significant step towards undermining the dominance of their ideological opponents.