The Historical Evolution of Commons in Flanders: Results from a Microstudy (18Th-19Th Century) ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belgian Beer Experiences in Flanders & Brussels

Belgian Beer Experiences IN FLANDERS & BRUSSELS 1 2 INTRODUCTION The combination of a beer tradition stretching back over Interest for Belgian beer and that ‘beer experience’ is high- centuries and the passion displayed by today’s brewers in ly topical, with Tourism VISITFLANDERS regularly receiving their search for the perfect beer have made Belgium the questions and inquiries regarding beer and how it can be home of exceptional beers, unique in character and pro- best experienced. Not wanting to leave these unanswered, duced on the basis of an innovative knowledge of brew- we have compiled a regularly updated ‘trade’ brochure full ing. It therefore comes as no surprise that Belgian brew- of information for tour organisers. We plan to provide fur- ers regularly sweep the board at major international beer ther information in the form of more in-depth texts on competitions. certain subjects. 3 4 In this brochure you will find information on the following subjects: 6 A brief history of Belgian beer ............................. 6 Presentations of Belgian Beers............................. 8 What makes Belgian beers so unique? ................12 Beer and Flanders as a destination ....................14 List of breweries in Flanders and Brussels offering guided tours for groups .......................18 8 12 List of beer museums in Flanders and Brussels offering guided tours .......................................... 36 Pubs ..................................................................... 43 Restaurants .........................................................47 Guided tours ........................................................51 List of the main beer events in Flanders and Brussels ......................................... 58 Facts & Figures .................................................... 62 18 We hope that this brochure helps you in putting together your tours. Anything missing? Any comments? 36 43 Contact your Trade Manager, contact details on back cover. -

2015 BJCP Beer Style Guidelines

BEER JUDGE CERTIFICATION PROGRAM 2015 STYLE GUIDELINES Beer Style Guidelines Copyright © 2015, BJCP, Inc. The BJCP grants the right to make copies for use in BJCP-sanctioned competitions or for educational/judge training purposes. All other rights reserved. Updates available at www.bjcp.org. Edited by Gordon Strong with Kristen England Past Guideline Analysis: Don Blake, Agatha Feltus, Tom Fitzpatrick, Mark Linsner, Jamil Zainasheff New Style Contributions: Drew Beechum, Craig Belanger, Dibbs Harting, Antony Hayes, Ben Jankowski, Andew Korty, Larry Nadeau, William Shawn Scott, Ron Smith, Lachlan Strong, Peter Symons, Michael Tonsmeire, Mike Winnie, Tony Wheeler Review and Commentary: Ray Daniels, Roger Deschner, Rick Garvin, Jan Grmela, Bob Hall, Stan Hieronymus, Marek Mahut, Ron Pattinson, Steve Piatz, Evan Rail, Nathan Smith,Petra and Michal Vřes Final Review: Brian Eichhorn, Agatha Feltus, Dennis Mitchell, Michael Wilcox TABLE OF CONTENTS 5B. Kölsch ...................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION TO THE 2015 GUIDELINES............................. IV 5C. German Helles Exportbier ...................................... 9 Styles and Categories .................................................... iv 5D. German Pils ............................................................ 9 Naming of Styles and Categories ................................. iv Using the Style Guidelines ............................................ v 6. AMBER MALTY EUROPEAN LAGER .................................... 10 Format of a -

Archeologienota Ichtegem Moerdijkstraat 94 Verslag Van Resultaten

2018.085 Archeologienota Ichtegem Moerdijkstraat 94 Verslag van Resultaten Bert ACKE en Maarten BRACKE 9-7-2018 2018.085 2 Archeologienota Ichtegem Moerdijkstraat 94 Titel: Archeologienota Ichtegem Moerdijkstraat 94 Erkend archeoloog: Maarten Bracke, OE/ERK/Archeoloog/2015/00036 Auteurs: Bert Acke en Maarten Bracke Kaartmateriaal opgemaakt door Archeopunt gcv; Uittreksels uit CartoWeb.be met toelating van het Nationaal Geografisch Instituut C18020 - www.ngi.be Projectcode bureauonderzoek: 2018F110 Intern projectnummer: 2018.085 Locatiegegevens: Ichtegem Moerdijkstraat 94 Lambertcoördinaten onderzoeksgebied: X: 54943,8 en Y: 200034,69; X: 55135,9 en Y: 200161,76 Kadastergegevens: Ichtegem, afdeling 1, sectie A, percelen 634A2, 634D2, 634E2, 634W, 634X, 634Y, 634Z, 635M (zie figuur 8) Topografische kaart: zie figuur 6 en 7 Betrokken actoren: Bert Acke (assistent-archeoloog), Maarten Bracke (erkend archeoloog), Kris Van Quaethem (assistent-archeoloog) en Frederik Demeyere (contactpersoon initiatiefnemer) Wetenschappelijke advisering: / Plaats en datum: Zelzate, 09/07/2018 © Acke & Bracke bvba, Damstraat 206A, 9180 Moerbeke-Waas. De auteurs aanvaarden geen aansprakelijkheid voor eventuele schade voortvloeiend uit het gebruik van de resultaten van dit onderzoek of de toepassing van de adviezen. Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar worden gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke wijze ook, zonder voorafgaandelijke schriftelijke toestemming van de auteurs. 2018.085 3 Archeologienota Ichtegem Moerdijkstraat 94 1. INLEIDING 4 1.1. WETTELIJK KADER 4 1.2. ONDERZOEKSOPDRACHT 4 1.2.1. VRAAGSTELLING 4 1.2.2. RANDVOORWAARDEN 4 1.3. WERKWIJZE EN STRATEGIE 5 1.3.1. MOTIVERING ONDERZOEKSSTRATEGIE 5 1.3.2. ORGANISATIE VAN HET VOORONDERZOEK 6 1.3.3. -

Hulpverleningszones Van Belgïe Zones De Secours De Belgique 11/2017 ESSEN HOOGSTRATEN

Hulpverleningszone Brandweer Zone Taxandria Brandweer Rand Zone Antwerpen Hulpverleningszone 1 Hulpverlenings- Hulpverleningszone zone Waasland Hulpverleningszone Meetjesland Brandweer zone Noord-Limburg Kempen Hulpverlenings- zone Centrum Hulpverlenings- Hulpverleningszone zone Oost Rivierenland Brandweerzone Midwest Brandweerzone Brandweer Hulpverlenings- Hulpverleningszone Oost-Limburg Westhoek zone West Hulpverleningszone Zuid-Oost Zuidwest Hulpverleningszone Hulpverleningszone DBDMH Oost Vlaamse Ardennen Brussel Hulpverleningszone SIAMU Fluvia Bruxelles Zone de secours Zone de secours Zone de secours du Brabant wallon de Hesbaye Liège Zone 2 Wallonie Picarde IILE-SRI Zone de secours Vesdre – Hoëgne & Plateau Zone de secours Zone de secours Hainaut-Centre Zone de secours HEMECO Zone de NAGE secours Zone de secours 5 Zone de secours Val de Warche Amblève Lienne Hainaut-Est (ZS5 W.A.L.) Sambre Zone DG Zone de secours DINAPHI Zone de secours de Luxembourg Hulpverleningszones van Belgïe Zones de secours de Belgique 11/2017 ESSEN HOOGSTRATEN BAARLE-HERTOG WUUSTWEZEL RAVELS KALMTHOUT MERKSPLAS Brandweer Zone Hulpverleningszone Rand RIJKEVORSEL STABROEK Taxandria BRECHT ARENDONK TURNHOUT KAPELLEN OUD- BRASSCHAAT BEERSE TURNHOUT VOSSELAAR MALLE RETIE SCHOTEN SCHILDE Brandweer Zone ZOERSEL LILLE ANTWERPEN DESSEL KASTERLEE Antwerpen WIJNEGEM ZWIJNDRECHT VORSELAAR WOMMELGEM ZANDHOVEN MOL BORSBEEK RANST Brandweer zone MORTSEL BOECHOUT GROBBENDONK HERENTALS GEEL BALEN EDEGEM OLEN Kempen NIJLEN HOVE HERENTHOUT HEMIKSEM MEERHOUT AARTSELAAR LINT -

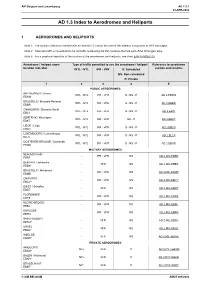

AD 1.3 Index to Aerodromes and Heliports

23-APR-2020 AIP Belgium and Luxembourg AD 1.3-1 23-APR-2020 AD 1.3 Index to Aerodromes and Heliports 1 AERODROMES AND HELIPORTS Note 1: The location indicators marked with an asterisk (*) cannot be used in the address component of AFS messages. Note 2: National traffic is considered to be all traffic not leaving the EU countries that are part of the Schengen area. Note 3: For a graphical depiction of the location of the aerodromes and heliports, see chart ENR 6-INDEX.09. Aerodrome / heliport name Type of traffic permitted to use the aerodrome / heliport Reference to aerodrome location indicator INTL - NTL IFR - VFR S: Scheduled section and remarks NS: Non-scheduled P: Private 1 2 3 4 5 PUBLIC AERODROMES ANTWERPEN / Deurne INTL - NTL IFR - VFR S - NS - P AD 2.EBAW EBAW BRUSSELS / Brussels-National INTL - NTL IFR - VFR S - NS - P AD 2.EBBR EBBR CHARLEROI / Brussels South INTL - NTL IFR - VFR S - NS - P AD 2.EBCI EBCI KORTRIJK / Wevelgem INTL - NTL IFR - VFR NS - P AD 2.EBKT EBKT LIÈGE / Liège INTL - NTL IFR - VFR S - NS - P AD 2.EBLG EBLG LUXEMBOURG / Luxembourg INTL - NTL IFR - VFR S - NS - P AD 2.ELLX ELLX OOSTENDE-BRUGGE / Oostende INTL - NTL IFR - VFR S - NS - P AD 2.EBOS EBOS MILITARY AERODROMES BEAUVECHAIN - IFR - VFR NS AD 2.MIL-EBBE EBBE BERTRIX / Jehonville - VFR NS AD 2.MIL-EBBX EBBX* BRUSSELS / Melsbroek - IFR - VFR NS AD 2.MIL-EBMB EBMB CHIÈVRES - IFR - VFR NS AD 2.MIL-EBCV EBCV* DIEST / Schaffen - VFR NS AD 2.MIL-EBDT EBDT FLORENNES - IFR - VFR NS AD 2.MIL-EBFS EBFS KLEINE-BROGEL - IFR - VFR NS AD 2.MIL-EBBL EBBL KOKSIJDE - -

New Acquisition of 13 Housing Units and Completion of 56 Additional Units

PRESS RELEASE Brussels, under embargo until June 7, 2021, 5:45 PM CET New acquisition of 13 housing units and completion of 56 additional units 1. Acquisition of an existing building in Oudenburg Inclusio purchased at the end of May 2021 a property located in Oudenburg (West Flanders). The building consists of 13 apartments and a common laundry room. These affordable units are leased to the Social Rental Agency “Woondienst JOGI” (Jabbeke, Oudenburg, Gistel, Ichtegem, Torhout) and to the Center for Public Social Assistance of Oudenburg. 2. Completion of two projects In addition, at the beginning of June, Inclusio completed two new affordable housing projects : one in Wallonia and the second one in Brussels. Inclusio’s own development team was in charge of these two reconversion projects. 2.1. Clos de l’Auflette – Phase 3 (Mons) In Mons (Cuesmes), the third phase of the “Clos de l’Auflette” project was completed on June 1st, 2021. The project consists in the complete refurbishment of two old school buildings in individual apartments leased for a period of 9 years to the Social Rental Agency “Mon(s) Logement”. The third phase counts 15 housing units (7 apartments with 2 bedrooms and 8 apartments with 3 bedrooms). Before reconversion After reconversion Inclusio SA/NV Avenue Herrmann-Debrouxlaan 40, 1160 Brussels, Belgium Page 1 of 3 www.inclusio.be – BE 0840.020.295 – Tel + 32 2 675 78 82 PRESS RELEASE Brussels, under embargo until June 7, 2021, 5:45 PM CET 2.2. Pavillon 7-9 (Schaerbeek) In Schaerbeek (Brussels), the apartments of the “Pavillon 7-9” project were completed in early June. -

Technical Guide Dwars Door West-Vlaanderen

Technical Guide Dwars door West-Vlaanderen UCI Europe Tour 1.1 Sunday 4th of March, 2018 Nieuwpoort - Ichtegem KVC Ichtegem Sportief W www.ddwvl.be E [email protected] Edited by Frederik Van Eyck F www.facebook.be/ddwvl Een nieuwe wielerlente, een nieuw geluid… opnieuw een nieuwe wielerkoers. In 2017 was onze nieuwe boreling Dwars door West-Vlaanderen een succesverhaal. Ondanks het slechte weer kregen we een flandrienfinale om vingers en duimen af te likken : Jos van Emden won het in een slopende spurt van de jonge Zwitser Sylvan Dillier. Beiden wonnen later in de Giro ‘d Italia een rit. Onze wedstrijd kreeg in 2017 extra glans daar we de kans kregen te mogen toetreden tot de Napoleon Games Cup, met live uitzending op de nationale TV zender VTM. Een enorme meerwaarde voor onze wielergemeente en onze wielerclub. Meer dan een half miljoen kijkers volgden vanuit de huiskamer het wielerspektakel. Meteen komen we in 2018 met een nieuwe wedstrijd op de proppen : De Omloop van de Westhoek-Memorial Stive Vermaut voor dames Elite UCI. Beide wedstrijden starten in Nieuwpoort en kennen hun finale in Ichtegem. Met Dwars door West-Vlaanderen ontwaakt het wielrennen uit zijn winterslaap en als het een beetje meezit proeven we al iets van de lente gedurende onze hoogdag. Deze wedstrijd is dan ook al jaren een mooie voorproef, het ingangsexamen voor de komende wielerklassiekers. Hoe je het ook draait of keert, Ichtegem is en blijft een wielergekke gemeente. Het is altijd een apotheose om de wielerkaravaan Ichtegem te zien binnenrijden. Onze wedstrijd is en blijft een venster op West-Vlaanderen : de wielerwereld kijkt mee naar de wedstrijden die hier gereden worden. -

Een Nieuwe Huisstijl

LEEFT! 2-maandelijks informatieblad voor Adinkerke en De Panne 31e jaargang n° 2 • Afgiftekantoor 8660 De Panne 05 I 06 Een nieuwe huisstijl Eenheid als sleutelwoord naar de vele bogen die je terug- De kleuren spreken voor zich: het Adinkerke en De Panne en ook vindt op het openbaar domein in blauw verwijst naar de zee en het de verschillende diensten van het onze gemeente. De rechte lijn bo- geel-groen doet denken aan onze OCMW en van de gemeente … venaan oogt krachtig en loopt mooi prachtige natuur, maar ook aan elk heeft zijn eigen karakter en zijn evenwijdig met de bovenste rand ons brede strand. voorwoord eigen doelstellingen. Maar samen van het blad. staan we zo veel sterker. Daarom De letters ogen modern en ook de Met enige fierheid stel ik u het is er gekozen voor eenheid, dit wil schrijfwijze is apart. De woor- nieuwe logo en de nieuwe slogan zeggen één logo voor de beide den ‘de’ en ‘panne’ van onze gemeente voor. deelgemeenten en voor alle Niet dat het oude logo niet goed diensten samen. Dat moet meer was … maar we zijn toch op zorgen voor een grotere zoek gegaan naar iets anders. herkenbaarheid. En dat actieve natuur We willen immers een dynamisch moet er dan weer voor zor- bestuur zijn en ons aanpassen gen dat we ons als toeristi- aan een maatschappij die snel sche gemeente duidelijker kun- verandert. Dus moeten we ook nen positioneren op de nationale een logo hebben dat modern en en zelfs op de internationale kaart. actieve dynamisch overkomt. natuur actieve natuur We zullen dat logo vanaf nu Een krachtig concept consequent gebruiken, in al De ontwerpers van de huisstijl kre- actieve onze communicatie. -

Linkebeek 10.60%

Geografische indicatoren (gebaseerd op Census 2011) De referentiedatum van de Census is 01/01/2011. Filters: Buitenlanders met een Europese nationaliteit België Gewest Provincie Arrondissement Gemeente Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Oudenaarde Lierde 0.29% Provincie West-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Roeselare Lichtervelde 0.44% Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Aalst Herzele 0.49% Arrondissement Diksmuide Koekelare 0.52% Provincie West-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Kortrijk Anzegem 0.52% Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Gent Oosterzele 0.54% Provincie West-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Roeselare Ledegem 0.55% Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Aalst Lede 0.58% Arrondissement Diksmuide Houthulst 0.60% Arrondissement Kortrijk Lendelede 0.60% Provincie West-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Oostende Ichtegem 0.61% Arrondissement Diksmuide Kortemark 0.62% Arrondissement Oostende Oudenburg 0.62% Arrondissement Dendermonde Laarne 0.67% Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Oudenaarde Maarkedal 0.68% Provincie West-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Brugge Zedelgem 0.71% Arrondissement Aalst Erpe-Mere 0.71% Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen Kluisbergen 0.73% Arrondissement Oudenaarde Zingem 0.75% Provincie Vlaams-Brabant Arrondissement Halle-Vilvoorde Pepingen 0.76% Provincie West-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Roeselare Staden 0.76% Arrondissement Dendermonde Berlare 0.77% Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Oudenaarde Zwalm 0.77% Provincie West-Vlaanderen Arrondissement Ieper Vleteren 0.78% Arrondissement Oudenaarde Brakel 0.78% Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen -

BDO Benchmark Gemeenten

BDO-BENCHMARK GEMEENTEN 2017 vs. 2016 PROVINCIE WEST-VLAANDEREN 1 INLEIDING Dit rapport toont u vrijblijvend enkele kerncijfers voor uw gemeente en de gemeenten binnen uw provincie. In totaal worden 6 kerncijfers getoond en vergeleken met het vorige boekjaar (2017 vs. 2016). De betekenis van deze cijfers/ratio’s wordt opgenomen in de bijlage bij deze analyse. De bijlage bevat ook nog 3 extra kerncijfers. Via de en knoppen op de inhoudsopgave kunt u snel en efficiënt door het rapport scrollen. Via de knoppen en komt u respectievelijk terug op de inhoudsopgave of bijlagen. Indien u hierover meer info of een toelichting wenst, aarzel niet om ons te . Veel leesplezier, BDO Public Sector september 2018 2 INHOUDSOPGAVE Inwoners provincie (samenstelling gemeenten) 3 INHOUDSOPGAVE - BIJLAGEN Realisatiegraad investeringen APB per inwoner OOV per inwoner 4 AANDACHTSPUNTEN 4 • Cijfers jaarrekening 2017 - 2016 zoals gepubliceerd door ABB • 10 gemeenten over de provincies heen zijn niet opgenomen omwille van laattijdige publicatie van de cijfers • 4 categorieën van gemeenten op basis van 1/1/2018: <10.000 inwoners XS >10.000 en < 20.000 inwoners S >20.000 en < 30.000 inwoners M >30.000 inwoners L • Resultaten worden getoond voor uw bestuur, globaal en per categorie • in EUR totaal, gemiddeld, per inwoner • voor de top 3 (hoogste of laagste) 5 INWONERS PROVINCIE WEST-VL. Kleinste gemeenten 9x L Mesen 1.040 499k inw. Spiere-Helkijn 2.087 Zuienkerke 2.730 9x M Lo-Reninge 3.289 210k inw. Grootste gemeenten 25x S Brugge 118.284 335k inw. Kortrijk 76.265 Oostende 71.332 19x XS gemiddeld Roeselare 62.301 126k inw. -

Deel 2.2. Oostende

Vervoergebied Oostende 1. Overzicht van vervoerbewijzen en tarieven Vervoergebied Oostende bevolking. 228.990 243 ALVERINGEM 4.898 250 KOEKELARE 8.254 244 BREDENE 14.982 251 KOKSIJDE 21.033 245 DE HAAN 11.847 252 MIDDELKERKE 17.690 246 DE PANNE 9.961 253 NIEUWPOORT 10.856 247 DIKSMUIDE 15.636 254 OOSTENDE 68.594 248 GISTEL 11.159 255 OUDENBURG 8.884 249 ICHTEGEM 13.340 256 VEURNE 11.856 2. Aan het vervoergebied toegewezen lijnen film lijn prodatanr 59 Belbus Diksmuide - Koekelare - Ichtegem 5059 KT Tramlijn Knokke - De Panne (deels) 5500 41 Diksmuide - Nieuwpoort 5641 47 Belbus Kortemark - Diksmuide 5647 49 Belbus Diksmuide - Pervijze 5649 53 Diksmuide - Leke - Oostende 5653 57 Belbus Veurne - Zoutenaaie 5657 58 Ieper - Diksmuide - Moere - Oostende 5658 64 Diksmuide - Torhout - Aartrijke 5664 1 Centrumbus Oostende 5901 4 Oostende Marie-José - Bredene 5904 5 Raversijde - Oostende - Stene 5905 6 Stene - Station - Raversijde 5906 7 Oostende Station - Steense Dijk 5907 9 Oostende Marie-José - Bredene 5909 21 Oostende - Oudenburg - Eernegem 5921 22 Oostende - Zandvoorde - Oudenburg - Ettelgem 5922 23 Oostende - Oudenburg - Westkerke 5923 24 Avondlijn Oostende Meiboom - Zandvoorde 5924 46 Oostende - Klemskerke 5946 50 Oostende Station - Meiboom - Gistel 5950 51 Oostende - Gistel - Eernegem - Torhout 5951 55 De Panne-Adinkerke 5955 56 Veurne - De Panne via Oosthoek 5956 59 Belbus Veurne - Roesbrugge 5959 60 Oostende-Leffinge 5960 69 Oostende-Nieuwpoort-Veurne 5969 3. Overzicht versterkingsritten A. Specifieke versterkingsritten in het vervoergebied -

West-Vlaanderen: Deelnemende Sportclubs "Maand Van De Sportclub 2021"

West-Vlaanderen: Deelnemende Sportclubs "Maand van de Sportclub 2021" Gemeente /stad Naam sportclub Sporttak Website en/of sociale media Mailadres Telefoonnummer Ardooie; Dansschool Starlight Dansen dansschoolstarlight.be [email protected] 0498845118 Judoclub Ardooie (3073) Judoma https://www.judoclubardooie.be [email protected] 0472955446 KVC ARDOOIE Voetbal www.kvcardooie.be [email protected] 0478480641 Avelgem; Karate Do Karate https://karate.vlaanderen/ [email protected] 0484/417503 Koninklijke Basket Avelgem Basketbal www.basketavelgem.be / [email protected] 0474676889 www.facebook.com/KoninklijkebasketAvelgem / Young Dance4friends Dansen www.dance4friends.be [email protected] 0470850750 Dance4friends Dansen www.dance4friends.be [email protected] 0470850750 Tennisclub Avelgem / GO4TennisA Tennis www.tcavelgem.be [email protected] +32 483 570292 www.kerdavo.be; FaceBook & Instagram: Damesvolley Volleybalclub Kerdavo Avelgem volleybal Kerdavo Avelgem. [email protected] 0472 740 056 Beernem Goodheart Linedancers Dansen www.goodheartlinedancers.com [email protected] 0473 53 37 41 WTC KONINKLIJKE VELOSPORT OEDELEM Wielrennen geen [email protected] B-EASYDIVERS VZW Duiken WWW.b-easydivers.be [email protected] +32468308717 Mc hulstlo Motorcross Facebook mc hulstlo [email protected] 0478276707 Rugbyclub Beernem Rugby @rugbyclubbeernem [email protected] 0486213940 Facebook: Sint-Joris Sportief Website: KFC Sint-Joris Sportief Voetbal kfcsintjorissportief.peepl.be