STRATEG EYES: Workplace Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE 300 CLUB (39 Players)

THE 300 CLUB (39 players) App Player Club/s Years 423 Cameron Smith Melbourne 2002-2020 372 Cooper Cronk Melbourne, Sydney Roosters 2004-2019 355 Darren Lockyer Brisbane 1995-2011 350 Terry Lamb Western Suburbs, Canterbury 1980-1996 349 Steve Menzies Manly, Northern Eagles 1993-2008 348 Paul Gallen Cronulla 2001-2019 347 Corey Parker Brisbane 2001-2016 338 Chris Heighington Wests Tigers, Cronulla, Newcastle 2003-2018 336 Brad Fittler Penrith, Sydney Roosters 1989-2004 336 John Sutton South Sydney 2004-2019 332 Cliff Lyons North Sydney, Manly 1985-1999 330 Nathan Hindmarsh Parramatta 1998-2012 329 Darius Boyd Brisbane, St George Illawarra, Newcastle 2006-2020 328 Andrew Ettingshausen Cronulla 1983-2000 326 Ryan Hoffman Melbourne, Warriors 2003-2018 325 Geoff Gerard Parramatta, Manly, Penrith 1974-1989 324 Luke Lewis Penrith, Cronulla 2001-2018 323 Johnathan Thurston Bulldogs, North Queensland 2002-2018 323 Adam Blair Melbourne, Wests Tigers, Brisbane, Warriors 2006-2020 319 Billy Slater Melbourne 2003-2018 319 Gavin Cooper North Queensland, Gold Coast, Penrith 2006-2020 318 Jason Croker Canberra 1991-2006 317 Hazem El Masri Bulldogs 1996-2009 316 Benji Marshall Wests Tigers, St George Illawarra, Brisbane 2003-2020 315 Paul Langmack Canterbury, Western Suburbs, Eastern Suburbs 1983-1999 315 Luke Priddis Canberra, Brisbane, Penrith, St George Illawarra 1997-2010 313 Steve Price Bulldogs, Warriors 1994-2009 313 Brent Kite St George Illawarra, Manly, Penrith 2002-2015 311 Ruben Wiki Canberra, Warriors 1993-2008 309 Petero Civoniceva Brisbane, -

Sir Peter Leitch Club at MT SMART STADIUM, HOME of the MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS

Sir Peter Leitch Club AT MT SMART STADIUM, HOME OF THE MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS 27th July 2016 Newsletter #132 Parker v Haumono Photos courtesy of www.photosport.nz At the Parker Fight in Christchurch Great to catch up with the legend Me and Butterbean who is doing Kevin Barry giving Mike Morton Monty Betham at the boxing. Monty some fantastic work in the communi- from the Mad Butcher some stick left on Tuesday for the Rio Olympics ty. Very proud of this boy. after Mike won the meat raffle in as part of Sky TV’s team. Top man! the pub (no it was not mad butcher meat). Me and my mate Dexter ready to rock My grandson Matthew caught up The boys ready to hit the town in the night away in Christchurch. with Joseph Parker after his win in Christchurch. Nino, Rodney, Butch Christchurch. and Daniel. Was great to catch up with my old mate, international boxing com- mentator, Colonel Bob Sheridan. Bob is based in Las Vegas and has called over 10,000 fights including Muhammed Ali, George Foreman and Larry Holmes to name a few. He has been inducted into the boxing Hall of Fame and is a top bloke. Also at the boxing 3 former Kiwis Logan Edwards, Justin Wallace, Mark Woods. Hi all Feel free to share this coverage with your friends & ust wanted to give you a heads up on the feature community .. that screened yesterday on The Hui (TV3) about J the NZRL Taurahere camp on the Gold Coast this Watch full feature here month. -

23Rd June.Indd

The Norfolk ISLANDER The World of Norfolk’s Community Newspaper for more than 45 Years FOUNDED 1965 Successors to - The Norfolk Island Pioneer c. 1885 The Weekly News c 1932 : The Norfolk Island Monthly News c. 1933 The N.I. Times c. 1935 : Norfolk Island Weekly c. 1943 : N.I.N.E. c. 1949 : W.I.N. c. 1951 : Norfolk News c. 1965 Volume 47, No. 21 SATURDAY, 23rd JUNE 2012 Price $2.75 incl GST Marine Safety Legislation Update Minister for Tourism, Industry and Development, Hon Andre Nobbs is pleased to advise that the Marine Safety Working Group met last week to approve the final steps in the preparation of the Marine Safety Legislation Drafting Instructions. It is then to be finally approved by me and forwarded to Legislative Counsel to draft the Norfolk Island Marine Safety Bill. The Working Group is also supportive of a radio information exchange regarding the work that has been carried out to date and the practical outcomes being sought. “Following this process I am hopeful that the Bill will be tabled in the Legislative Assembly at the August meeting of the Parliament, following upon which Members of Parliament, along with interested members of the local community will have further opportunity to have input prior to the Bill passing in the Parliament and becoming Law,” the Minister advised. “During the past eight months I have tried to Welcome to the facilitate opportunities for local stakeholders and interested members of the local community to have Wonderful World of input into the preparation of this Bill. -

Research Repository

RESEARCH REPOSITORY This is the author’s final version of the work, as accepted for publication following peer review but without the publisher’s layout or pagination. The definitive version is available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/466624 Miller, T. (1995) A short history of the penis. Social Text (43). pp. 1-26. http://researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/id/eprint/39914/ Copyright: © 1995 Duke University Press It is posted here for your personal use. No further distribution is permitted. 1995 “A Short History of the Penis.” Social Text 43: 1-26. cism, the encouragement of violence through the fear of castration, and the development and sustenance of nationalistic chauvinism, men's sport is now something significantly more, a useful place to do cultural analysis. Sport has been isolated as a site of the "expression of sexuality in men" (Reekie 33). As Alice Jardine notes, the last twenty years of gender criti- cism directs men to address a number of issues. In calling on them to be "talking your body, not talking about it," she presents a research program that looks at men and war, men and textual representation, and men and sport as its axes of concern (Jardine 61). This does not have to be a self- lacerating experience for men. It might, in fact, even leaven such processes. For while pain is a crucial component of most sports, sporting pain that is produced directly from contact with other bodies remains as gendered (male) as it is violent (Synnott 166). Despite its fashionability within left, feminist, and postcolonial literary theory, "the body" is of minimal interest to theorists when it plays sport. -

Sport Culture and the Media.Pdf

Sport culture-media 11/14/03 10:57 AM Page 1 I S SUE S in CULTURAL and MEDIA STUDIES I S SUE S in CULTURAL and MEDIA STUDIES SERIES EDITOR: STUART ALLAN Rowe Sport, Culture and the Media Second Edition Reviewer’s comments on the first edition: David Rowe “Marks the coming of age of the academic study of media sport.” Media, Culture & Society “The book is extremely well-written – ideal as a student text, yet also at the forefront of innovation.” International Review of Cultural Studies “A thoroughly worthwhile read and an excellent addition to the growing literature on media sport.” Sport, Education and Society Sport, Culture and the Media comprehensively analyses two of the most powerful cultural forces of our times: sport and media. It examines the ways in which media sport has established itself in contemporary everyday life, and how sport and media have made themselves mutually dependent. This new edition examines the latest developments in sports media, including: • Expanded material on new media sport and technology developments • Updated coverage of political economy, including major changes in the ownership of sports broadcasting • New scholarship and research on recent sports events like the Olympics and the World Cup, sports television and press, and theoretical developments in areas like Edition Second Sport, and Culture the Media globalization and spectatorship The first part of the book,“Making Media Sport”, traces the rise of the sports media and the ways in which broadcast and print sports texts are produced, the values and Sport, Culture and practices of those who produce them, and the economic and political influences on and implications of ‘the media sports cultural complex’.The second part,“Unmaking the Media Sports Text”,concentrates on different media forms – television, still photography, news reporting, film, live commentary, creative sports writing and new media sports technologies. -

Steve MASCORD Opposite from Steve Mascord)

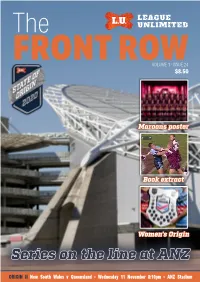

The FRONT ROWVOLUME 1 · ISSUE 24 $8.50 Maroons poster Book extract Women's Origin Series on the line at ANZ ORIGIN II New South Wales v Queensland - Wednesday 11 November 8:10pm - ANZ Stadium From the editor Tim Costello Hope Spring Origin is eternal? When we talk about the 'pointy end' of the season, this is it. The NRL is now long gone and we're deep into this new - unusual - Origin period in Australia (read more on that by Steve MASCORD opposite from Steve Mascord). Queensland overcame the odds to take game one, so inside Andrew Ferguson looks HEN Covid first hit, everyone back at the first Queensland outfit to overcome New South was fond of quoting the Wales way back during the days of interstate clashes in the early 20th century. Wspurious claim that the Chinese words for “crisis” and “opportunity” In the UK, the game has changed. It's finals time after were similar, or identical. the RFL and Super League agreed to cut short the season and play a six-team finals series over three weeks. More controversially, the powers that be have cut Toronto Nevertheless, in the vipers nest that is Wolfpack from the 2021 competition - more on that inside rugby league, some did manage to take it as well with Mascord. as a chance for seismic change. Channel Nine publicly criticised NRL CEO Todd We hope you enjoy this special edition of The Front Row. Greenberg, forcing his exit, and reduced its fee by a reported $28 million. In Britain, Toronto took the opportunity to pull out of Super League and Super League took the opportunity to kick them PRINTED IN out permanently. -

RUGBY LEAGUE and the LAW CHRIS DAVIES* Abstract Rugby

RUGBY LEAGUE AND THE LAW CHRIS DAVIES* Abstract Rugby league has been played in Australia for over a hundred years. While some cases originate from when the sport was semi-professional, the rise of professional leagues over the last two decades has also seen an increase in the involvement of the law. It is suggested that rugby league has been involved in more litigation than any other sport in Australia, with there being legal cases in areas such as competition law, restraint of trade, torts, criminal law and copyright. It is also suggested that some of these cases could have been avoided with better governance and administration. The draft system once implemented by rugby league, for example, was poorly designed and inevitably successfully challenged. However, other cases could have happened in a number of other sports and, at other times, other sports were actually involved in the litigation. Thus, there are a number of reasons why rugby league has experienced more litigation than other Australian sports. I INTRODUCTION The North Queensland Cowboys’ win in the 2015 National Rugby League (NRL) Grand Final was the culmination of over twenty years participation in a national competition, and represented the club’s first ever premiership. For South Sydney, meanwhile, the 2014 Premiership was its first in over forty years, the length of time this represented being indicated by the fact its previous premiership, in 1971, had been won in a competition organised by the New South Wales Rugby League (NSWLR). This competition, however, was not even the precursor of the NRL, Australia’s main rugby league competition having been run by the Australian Rugby League (ARL) in between those of the NSWRL and NRL. -

Defamation Law and Sport in Australia and New Zealand

669 A STORM DRIFTING BY? DEFAMATION LAW AND SPORT IN AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND Chris Davies* The law of defamation provides protection to people's reputations. An examination of the sports- related defamation cases in Australia and New Zealand indicates that such claims have been based on written comments, spoken words and also visual images. These cases can be internal comments made by those involved in a sport, as illustrated by the recent comments made by the coach of the Melbourne Storm, Craig Bellamy. However, as the recently decided case of Coates v Harbour Radio Pty Ltd indicates, most of the cases have involved comments made by people in the media rather than within the sport. An examination of defamation and sport, therefore, requires an examination of the sometimes delicate balance between the media's desire to report and comment on controversial sporting matters, and the desire of those involved in sport wishing to protect their reputations. I INTRODUCTION The lead up to the 2008 National Rugby League (NRL) Grand Final featured extensive media attention, not just in regard to the match, but also in relation to the criticisms made the previous week by Melbourne Storm coach, Craig Bellamy, concerning the performance of the NRL's judiciary. Bellamy and the Melbourne Storm were immediately fined $50,000 by the NRL, but this did not prevent members of the NRL judiciary from taking legal action. This is not the first time that the NRL judiciary has taken such defamation action: proceedings were taken against Phil Gould after similar criticisms.1 The President of the Australian Olympic Committee (AOC), John Coates, meanwhile, was awarded $360,000 damages against radio announcer Alan Jones in regard to his criticisms of Coates' handling of the Sally Robbins affair at the 2004 Athens Olympic Games.2 * Dr Chris Davies, BSc BA LLB (JCU) PhD (Syd), Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, Business and the Creative Arts, James Cook University. -

Athlete Endorsement Restrictions As Unreasonable Restraints of Trade

The University of New South Wales Master of Laws Thesis David Edward Thorpe Athlete Endorsement Restrictions as Unreasonable Restraints of Trade Supervisors: Professor Brendan Edgeworth and Deborah Healey of the Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales Admitted to the degree of Master of Laws by research: June, 2013 1 Preface The subject of athlete endorsement as a common law restraint of trade has been a largely ignored area of academic research or professional examination, in contrast to the plethora of articles and theses dealing with restraints of trade in sport, in particular salary caps and draft systems. As the first detailed analysis of the topic I have been very conscious that a broad approach to the subject matter was more valuable than a focus on a distinct aspect of it. It was necessary therefore, given the word limit of a Masters thesis, to pass over or merely touch upon material that, while relevant, was less important to the topic than that which is included. Issues concerned with inequality of bargaining power or insufficiency of contractual consideration as these relate to athlete endorsement are clearly relevant but were omitted to provide space to engage with the broader topic. For reasons of word length it has not been possible to consider in detail those arguments likely to be raised by sporting organisations that go to the question of reasonableness. Endorsement restraints are applied as a norm of the sports industry which itself suggests that the starting point of any research on this topic is to question the status quo. The imposition of endorsement restraints on athletes concerns matters of policy and fact that, although debated from time to time by athletes or in the media, has never been litigated. -

THE 300 CLUB (40 Players) App Player Club/S Years 424

THE 300 CLUB (40 players) App Player Club/s Years 424 Cameron Smith Melbourne 2002-2020 372 Cooper Cronk Melbourne, Sydney Roosters 2004-2019 355 Darren Lockyer Brisbane 1995-2011 350 Terry Lamb Western Suburbs, Canterbury 1980-1996 349 Steve Menzies Manly, Northern Eagles 1993-2008 348 Paul Gallen Cronulla 2001-2019 347 Corey Parker Brisbane 2001-2016 338 Chris Heighington Wests Tigers, Cronulla, Newcastle 2003-2018 336 Brad Fittler Penrith, Sydney Roosters 1989-2004 336 John Sutton South Sydney 2004-2019 333 Darius Boyd Brisbane, St George Illawarra, Newcastle 2006-2020 332 Cliff Lyons North Sydney, Manly 1985-1999 330 Nathan Hindmarsh Parramatta 1998-2012 328 Andrew Ettingshausen Cronulla 1983-2000 327 Adam Blair Melbourne, Wests Tigers, Brisbane, Warriors 2006-2020 326 Ryan Hoffman Melbourne, Warriors 2003-2018 325 Geoff Gerard Parramatta, Manly, Penrith 1974-1989 324 Luke Lewis Penrith, Cronulla 2001-2018 323 Johnathan Thurston Bulldogs, North Queensland 2002-2018 320 Benji Marshall Wests Tigers, St George Illawarra, Brisbane 2003-2020 319 Billy Slater Melbourne 2003-2018 319 Gavin Cooper North Queensland, Gold Coast, Penrith 2006-2020 318 Jason Croker Canberra 1991-2006 317 Hazem El Masri Bulldogs 1996-2009 315 Paul Langmack Canterbury, Western Suburbs, Eastern Suburbs 1983-1999 315 Luke Priddis Canberra, Brisbane, Penrith, St George Illawarra 1997-2010 313 Steve Price Bulldogs, Warriors 1994-2009 313 Brent Kite St George Illawarra, Manly, Penrith 2002-2015 311 Ruben Wiki Canberra, Warriors 1993-2008 309 Petero Civoniceva Brisbane, -

Annual Report 2005-2006

ANNUAL REPORT 2005-2006 NEW SOUTH WALES DEPARTMENT OF STATE AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 2005-2006 Annual Report Level 49 MLC Centre 19 Martin Place Sydney NSW 2000 GPO Box 5477 Sydney NSW 2001 Australia T: +61 2 9338 6600 F: +61 2 9338 6860 2 The Hon Morris Iemma MP Premier, Minister for State Development and Minister for Citizenship Level 39, Governor Macquarie Tower 1 Farrer Place SYDNEY NSW 2000 The Hon Frank Sartor MP Minister for Planning, Minister for Redfern Waterloo, Minister for Science and Medical Research and Minister Assisting the Minister for Health (Cancer) Level 34, Governor Macquarie Tower 1 Farrer Place SYDNEY NSW 2000 The Hon Sandra Nori MP Minister for Tourism and Sport and Recreation, Minister for Women and Minister Assisting the Minister for State and Regional Development Level 34, Governor Macquarie Tower 1 Farrer Place SYDNEY NSW 2000 The Hon David Campbell MP Minister for Water Utilities, Minister for Small Business, Minister for Regional Development and Minister for the Illawarra Level 36, Governor Macquarie Tower 1 Farrer Place SYDNEY NSW 2000 Dear Ministers In accordance with the Annual Reports (Departments) Act 1985, it is my pleasure to submit, for your information and presentation to Parliament, the Annual Report of the Department of State and Regional Development for the financial year ended 30th June 2006. The Report incorporates the Annual Reports for Tourism NSW, the Major Events Unit and the Office for Science and Medical Research which were added to the Department in March 2006. Yours sincerely Loftus Harris -

A Short History of the Penis.” Social Text 43: 1-26

1995 “A Short History of the Penis.” Social Text 43: 1-26. cism, the encouragement of violence through the fear of castration, and the development and sustenance of nationalistic chauvinism, men's sport is now something significantly more, a useful place to do cultural analysis. Sport has been isolated as a site of the "expression of sexuality in men" (Reekie 33). As Alice Jardine notes, the last twenty years of gender criti- cism directs men to address a number of issues. In calling on them to be "talking your body, not talking about it," she presents a research program that looks at men and war, men and textual representation, and men and sport as its axes of concern (Jardine 61). This does not have to be a self- lacerating experience for men. It might, in fact, even leaven such processes. For while pain is a crucial component of most sports, sporting pain that is produced directly from contact with other bodies remains as gendered (male) as it is violent (Synnott 166). Despite its fashionability within left, feminist, and postcolonial literary theory, "the body" is of minimal interest to theorists when it plays sport. Yet, as the principal site for the daily demonstration of the body, sport seems a critical space in which to assess the corporal mixture of the pri- mordially natural with the nostalgically postmodern. What does the suc- cessful body look like? How does it comport itself? Are examinations of male bodies part of a historic late modern shift towards the minute assessment of all bodies? Of course, there are other ways of talking about the male human subject than bodily contours, genetic assembly, public myth, and the cultural practices of men in sport.