Marking Loss, Memory, and Absence in the Korean Adoptee Diaspora A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DMZ Morning Half Day Tour

DMZ Morning Half Day Tour TOUR Special Tour No.1 TIME 08:00 ~ 14:30 DATE Available every day except Monday PRICE 39,000krw p/p (min.1person) INCLUSION Tour guide, transportation and entrance fees. Hotel Pick up – Imjingak Park – The Bridge of Freedom – The 3rd Infiltration Tunnel – DMZ ITINERYRA Theater/Exhibition Hall – Dora Observatory – Dorasan Station – Unification Village (Pass by) Y - Amethyst/Ginseng Center – Drop off at City Hall / Itaewon / Sheraton Grand Walkerhill Hotel. * This is the group package tour joining with other groups of people. * Hotel pick up service is available from Sheraton Grande Wakerhill and also other hotels in Seoul area. * Hotel sending service is available at Sheraton Grande Wakerhill for the people who are NOTE participating TAVI Summit2012. * Passport is needed on the tour day. * No special dress code for DMZ tour. * Personal action is not allowed at DMZ area. Information of Tourist Attraction Imjingak This park was built to console the refugees who left North Korea during the Korean War. A train called “the Iron horse wants to run” symbolizes the railway connecting the north and the south that was dismantled during the war. Also, at the park are the following attractions; Mangbaedan, an altar set up for refugees to bow in the direction of their ancestral graveyards; Freedom bridge, which was built to free 12,773 prisoners in 1953; Unification pond, which is in the shape of the Korean Peninsula; and the Peace bell. The 3rd Tunnel The 3rd Tunnel was discovered on October 17, 1978. It is located 52km from Seoul. Approximately 10,000 soldiers can move through this tunnel in 1 hour. -

Family, Mobile Phones, and Money: Contemporary Practices of Unification on the Korean Peninsula Sandra Fahy 82 | Joint U.S.-Korea Academic Studies

81 Family, Mobile Phones, and Money: Contemporary Practices of Unification on the Korean Peninsula Sandra Fahy 82 | Joint U.S.-Korea Academic Studies Moving from the powerful and abstract construct of ethnic homogeneity as bearing the promise for unification, this chapter instead considers family unity, facilitated by the quotidian and ubiquitous tools of mobile phones and money, as a force with a demonstrated record showing contemporary practices of unification on the peninsula. From the “small unification” (jageun tongil) where North Korean defectors pay brokers to bring family out, to the transmission of voice through the technology of mobile phones illegally smuggled from China, this paper explores practices of unification presently manifesting on the Korean Peninsula. National identity on both sides of the peninsula is usually linked with ethnic homogeneity, the ultimate idea of Koreanness present in both Koreas and throughout Korean history. Ethnic homogeneity is linked with nationalism, and while it is evoked as the rationale for unification it has not had that result, and did not prevent the ideological nationalism that divided the ethnos in the Korean War.1 The construction of ethnic homogeneity evokes the idea that all Koreans are one brethren (dongpo)—an image of one large, genetically related extended family. However, fissures in this ideal highlight the strength of genetic family ties.2 Moving from the powerful and abstract construct of ethnic homogeneity as bearing the promise for unification, this chapter instead considers family unity, facilitated by the quotidian and ubiquitous tools of mobile phones and money, as a force with a demonstrated record showing “acts of unification” on the peninsula. -

Metro Lines in Gyeonggi-Do & Seoul Metropolitan Area

Gyeongchun line Metro Lines in Gyeonggi-do & Seoul Metropolitan Area Hoeryong Uijeongbu Ganeung Nogyang Yangju Deokgye Deokjeong Jihaeng DongducheonBosan Jungang DongducheonSoyosan Chuncheon Mangwolsa 1 Starting Point Destination Dobongsan 7 Namchuncheon Jangam Dobong Suraksan Gimyujeong Musan Paju Wollong GeumchonGeumneungUnjeong TanhyeonIlsan Banghak Madeul Sanggye Danngogae Gyeongui line Pungsan Gireum Nowon 4 Gangchon 6 Sungshin Baengma Mia Women’s Univ. Suyu Nokcheon Junggye Changdong Baekgyang-ri Dokbawi Ssangmun Goksan Miasamgeori Wolgye Hagye Daehwa Juyeop Jeongbalsan Madu Baekseok Hwajeong Wondang Samsong Jichuk Gupabal Yeonsinnae Bulgwang Nokbeon Hongje Muakjae Hansung Univ. Kwangwoon Gulbongsan Univ. Gongneung 3 Dongnimmun Hwarangdae Bonghwasan Sinnae (not open) Daegok Anam Korea Univ. Wolgok Sangwolgok Dolgoji Taereung Bomun 6 Hangang River Gusan Yeokchon Gyeongbokgung Seokgye Gapyeong Neunggok Hyehwa Sinmun Meokgol Airport line Eungam Anguk Changsin Jongno Hankuk Univ. Junghwa 9 5 of Foreign Studies Haengsin Gwanghwamun 3(sam)-ga Jongno 5(o)-gu Sinseol-dong Jegi-dong Cheongnyangni Incheon Saejeol Int’l Airport Galmae Byeollae Sareung Maseok Dongdaemun Dongmyo Sangbong Toegyewon Geumgok Pyeongnae Sangcheon Banghwa Hoegi Mangu Hopyeong Daeseong-ri Hwajeon Jonggak Yongdu Cheong Pyeong Incheon Int’l Airport Jeungsan Myeonmok Seodaemun Cargo Terminal Gaehwa Gaehwasan Susaek Digital Media City Sindap Gajwa Sagajeong Dongdaemun Guri Sinchon Dosim Unseo Ahyeon Euljiro Euljiro Euljiro History&Culture Park Donong Deokso Paldang Ungilsan Yangsu Chungjeongno City Hall 3(sa)-ga 3(sa)-ga Yangwon Yangjeong World Cup 4(sa)-ga Sindang Yongmasan Gyeyang Gimpo Int’l Airport Stadium Sinwon Airprot Market Sinbanghwa Ewha Womans Geomam Univ. Sangwangsimni Magoknaru Junggok Hangang River Mapo-gu Sinchon Aeogae Dapsimni Songjeong Office Chungmuro Gunja Guksu Seoul Station Cheonggu 5 Yangcheon Hongik Univ. -

31 Hongkong and South Corea

Victoria Peak, Hong Kong Starts Hong Kong 3 Days – 2 Nights From $549* Day 1 Arrive Hong Kong Day 3 Depart from Hong Kong Welcome to Hong Kong. Meet your Global Holidays tour Check out & proceed to the airport for your onward destination. Manager/LocalGuide at the arrivals and proceed Hotel. Remaining Breakfast day will be at Leisure. Tour Highlights Hong Kong Day 2 Hong Kong city tour Half - Day morning tour of Hong Kong Island Witness Aberdeen's floating community Today get to know the ins and outs of Hong Kong island during Ride the Victoria Peak Tram Shop for bargains at Stanley Market this comprehensive half-day tour that touches on all the Pass by picturesque Repulse Bay Watch Craftsmen at work in a Jewelry factory. highlights. Learn about the history and culture as you visit major landmarks with your expert local guide. Make stops at Victoria Departure Dates & Prices Peak, Stanley Market and the traditional fishing village of Prices Departure Dates Aberdeen. Remaining day will be at Leisure Adult Child 02-11 Single Breakfast Any Date $549 $415 $740 Price Includes: Adult: Price per person based on 02/03 adults sharing a room 02 Night’s accommodation in 3*/4* Hotel with Breakfast Child : 02-11 years must share a room with 02/03 adults Ground Transportation by AC Deluxe Vehicle Infant : 0-23 Months is FREE Sightseeing as mentioned under tour highlights Max occupancy per room is 03 person (Excluding Infants) Service of english speaking guide Blue House, South Korea Korean Demilitarized Zone, South Korea Starts South Korea 3 Days – 2 Nights From $395* City Covered : Seoul Day 1 Seoul Tour Highlights Welcome to Seoul.Meet your Global Holidays tour SEOUL (Korea) Manager/LocalGuide at the arrivals and proceed Hotel. -

Dmz Full Day Tour

DMZ TOUR DMZ FULL DAY TOUR 08:30 ~ 17:00 (Lunch Included) US$67 Imjingak Pavilion → The Unification Bridge → ID Check → DMZ → Film Presentation → Exhibition Hall → The 3rd Infiltration Tunnel → Dora Observatory → Dorasan Station → Pass by Unification Village → Paju Shopping Outlet DMZ: Korea is the only divided country in the world. After the Korean War (June 25 1950 – July 27 1953), South Korea and North Korea established a border that cut the Korean peninsula roughly in half. Stretching for 2km on either side of this border is the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). Imjingak pavilion –The Unification Bridge – ID Check –DMZ –Film presentation -& Exhibition-Hall –The 3rdinfiltration tunnel – Dora observatory –Dorasan station –Pass by unification. It is strongly advised the attire should be casual with comfortable walking shoes as you will be walking inside tunnel. The guided tour will be followed with no one left astray as we move through the 3rd infiltration tunnel. (Every Monday – N/A) Paju Premium Outlets, Korea’s second Premium Outlet Center, is a one-hour drive from Seoul featuring 160 designer and name brand outlet stores at savings of 25% to 65% every day in an upscale, outdoor setting. (Some items may be excluded.) In addition to 160 stores, Paju Premium Outlets accommodates a food court with 600 seats and 20 restaurants & cafe to enhance the shopping enjoyment. Concierge service, stroller and wheelchair rentals and tour information are provided at the Information Center. Only 44 km (27 miles) from Seoul, the tunnel was discovered in October -

DMZ in Korea, the Scene of Movie 'The Interview'

DMZ in Korea, the Scene of Movie ‘The Interview’ The end of last year ‘2014’, the movie ‘The interview’ had brought enormous big issue all over the world. You would have seen many outdoor billboards of ‘The interview’ all over the streets. The movie story is A MC and a producer of talk show land an interview with North Korean dictator ‘Kim jong-un’, they are recruited by the CIA to turn their trip to Pyongyang into an assassination mission. Anyway, let’s visit ‘DMZ (Demilitarized Zone)’, the scene of the movie. The reality of division Korea into North and South It’s been 15 years, since I visited near Military Demarcation Line (MDL). When I was young, I visited ‘Unification Observatory’ with my family. The thing that I remembered was North residents who leading their life as usual over the MDL. I just felt surprising, the reason that even though it’s not quite far from South Korea, they had been living in a different world. I wondered before visiting DMZ again how I feel that after a long time. First of all, the DMZ is good for business because it’s one of the best tour programs in South Korea that many tourists can experience MDL of a divided country that world’s only. However at the same time, as a Korean, it was sad thing that it’s made into tour program, because millions of Korean families have been separated following the division in 1945 and the 1950 Korean War and left grief-stricken far more than half a century. -

The Loft Literary Center Announces 2018–19 Mirrors and Windows Fellows

The Loft Literary Center Open Book, Suite 200 1011 Washington Avenue South Minneapolis, MN 55415 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: CONTACT: Chris Jones 612-215-2589 [email protected] The Loft Literary Center Announces 2018–19 Mirrors and Windows Fellows Twelve Minnesota Emerging Children’s Writers of Color Selected for a Year-long Fellowship Program The Loft Literary Center is pleased to announce the recipients of the The Loft Mirrors and Windows Fellowship. While books for young readers is a thriving sector in publishing, those that are by or about Indigenous people and people of color are significantly underrepresented. This Fellowship’s focus is to mentor Indigenous writers and writers of color to write picture books, middle grade, and young adult literature, Mirrors and Windows. The name is inspired by Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop’s crucial essay, “Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors” (1990). The fellows will go through six different workshops with six different experts in the field, as well as be involved with annual Loft events such as Wordplay and Wordsmith. Fellows will also receive individual manuscript consultations. This program is funded by the Jerome Foundation and through Loft membership support. 2018–19 ENTRIES AND SELECTIONS The Loft Literary Center received 52 entries to the 2018–19 Loft Mirrors and Windows Fellowship. Three judges—the program’s community lead, and two of the workshop leaders—read through all applications and deliberated to the final twelve. 2018–19 FELLOWS The 2018-2019 cohort are: Saymoukda Vongsay, Vong Bidania, Tlahtoki Xochimeh, Taiyon Coleman, Venessa Fuentes, Shalini Gupta, Piyali Dalal, Marcelle Richards, Michael Torres, Zarlasht Niaz, Soojin Pate, and Maya Beck. -

Dr.Nina Smart

The Normandale Writing Center presents NORMANDALE WRITING FESTIVAL APRIL 7, 2016 ORGANIZED BY NORMANDALE’S WRITING CENTER ACTION COMMITTEE ABOUT OUR FESTIVAL: This festival, our seventh annual, is organized by the Writing Center Action Committee to expand the Writing Center’s mission to help students with all facets of their writing. Today, we celebrate the many ways students and the broader Normandale community use and enjoy writing. The interdisciplinary Writing Center Action Committee includes chair and Writing Center Director Kris Bigalk, Jenny Erickson, Amy Fladeboe, Robert Frame, Tom Maltman, Matt Mauch, Sadie Pendaz, Dee Larson-Quinn, Debra Sidd, Kim Socha, and Linda Tetzlaff. We thank everyone—presenters, helpers, Writing Center tutors, support staff, administrators, the Normandale Foundation, the President’s Diversity Council, and Phi Theta Kappa —who helped make this seventh annual festival possible. KEYNOTE SPEAKERS: At 11:o0 and 12:00 today, join us for the two keynote presentations of the festival. 11:00: DR. NINA SMART 12:00: REGINALD DWAYNE BETTS Location: Kopp Center Garden Room (K0462) FOOD & REFRESHMENTS: Both keynote presentations in the Kopp Center adjoin the cafeteria. Guests may bring food into the Garden Room during the presentation. 2 KEYNOTE SPEAKER BIOGRAPHIES DR. NINA SMART is a human rights activist, sociologist, and author who educates people about female genital mutilation (FGM) and works to eradicate the practice in Sierra Leone. Dr. Smart’s passion for human rights, academic expertise, and unique biography place her inside and outside of Sierra Leonean culture, allowing her to make important inroads. In 2004, Dr. Smart founded Servicing Wild Flowers –SWF International, a Los Angeles based non-profit NGO that raises awareness about FGM through lectures and presentations for students and socially conscious groups. -

The Dmz Tour Course Guidebook

THE DMZ TOUR COURSE GUIDEBOOK From the DMZ to the PLZ (Peace and Life Zone) According to the Korean Armistice Agreement of 1953, the cease-fire line was established from the mouth of Imjingang River in the west to Goseong, Gangwon-do in the east. The DMZ refers to a demilitarized zone where no military army or weaponry is permitted, 2km away from the truce line on each side of the border. • Establishment of the demilitarized zone along the 248km-long (on land) and 200km-long (in the west sea) ceasefire line • In terms of land area, it accounts for 0.5% (907km2) of the total land area of the Korean Peninsula The PLZ refers to the border area including the DMZ. Yeoncheon- gun (Gyeonggi-do), Paju-si, Gimpo-si, Ongjin-gun and Ganghwa-gun (Incheon-si), Cheorwon-gun (Gangwon-do), Hwacheon-gun, Yanggu- gun, Inje-gun and Goseong-gun all belong to the PLZ. It is expected that tourist attractions, preservation of the ecosystem and national unification will be realized here in the PLZ under the theme of “Peace and Life.” The Road to Peace and Life THE DMZ TOUR COURSE GUIDEBOOK The DMZ Tour Course Section 7 Section 6 Section 5 Section 4 Section 3 Section 2 Section 1 DMZ DMZ DMZ Goseong Civilian Controlled Line Civilian Controlled Line Cheorwon DMZ Yanggu Yeoncheon Hwacheon Inje Civilian Controlled Line Paju DMZ Ganghwa Gimpo Prologue 06 Section 1 A trail from the East Sea to the mountain peak in the west 12 Goseong•Inje 100km Goseong Unification Observatory → Hwajinpo Lake → Jinburyeong Peak → Hyangrobong Peak → Manhae Village → Peace & Life Hill Section 2 A place where traces of war and present-day life coexist 24 Yanggu 60km War Memoria → The 4th Infiltration Tunnel → Eulji Observatory → Mt. -

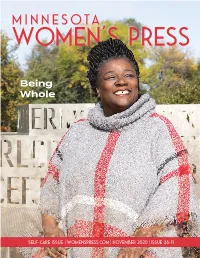

November 2020 | 3 Tapestry Practicing Self-Care Our Monthly Submissions from Readers

MINNESOTA WOMEN’S PRESS Being Whole GatekeepingSelf-Care Issue Issue | womenspress.com| womenspress.com | November | October 20202020 || IssueIssue 36-1136-10 MINNESOTA WOMEN’S PRESSPOWERFUL. EVERYDAY. WOMEN. Caring for myself is not self-indulgence. It is self-preservation. And that is an act of political warfare. PHOTO RODEL QUERUBIN QUERUBIN RODEL PHOTO — Audre Lorde What’s inside? Editor Letter 3 Regeneration Requires Wholeness Tapestry 4-5 Practicing Self-Care Perspective 6 Amanda Koonjebeharry Sun Yung Shin: Wholeness as Practice Page 18 2021 Themes 7 What to look forward to from MWP Contact Us MWP team GoSeeDo 8 Virtual and In-person Art, Flip the Script 651-646-3968 Publisher/Editor: Mikki Morrissette Identity 12-13 Submit a story: [email protected] Managing Editor: Sarah Whiting Jenna Gruen: Missing the Boat Subscribe: [email protected] Business Strategy Director: Shelle Eddy Art of Living 14-15 Advertise: [email protected] Digital Development: Mikki Morrissette Tia Keobounpheng: Unweaving Find a copy: womenspress.com/find-a-copy Photography/Design: Sarah Whiting BookShelf 16-17 Deneal Trueblood-Lynch: Releasing Secrets Associate Editor: Lydia Moran The Minnesota Women’s Press has been sharing the Trauma 18 stories of women since 1985, as one of the longest Advertising Sales: Shelle Eddy, Ashley Findlay, Amanda Koonjebeharry: Dancing Out of Dark continuously published feminist platforms in the Ryan Stevens country. It is distributed free at 500 locations. Health 22 Accounting: Fariba Sanikhatam Hedy Tripp: I Am a One-Breasted Woman Our mission: Amplify and inspire, with personal This month’s writers: Kate Brune, Suzanne Fenton, stories and action steps, the voice, vision, and In the News 23 Jenna Gruen, Tia Keobounpheng, Sun Yung Shin, leadership of powerful, everyday women. -

Renegotiating History: Representations of the Family in Post-1989 German Literature

RENEGOTIATING HISTORY: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE FAMILY IN POST-1989 GERMAN LITERATURE BY REGINE CRISER DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee Associate Professor Anke Pinkert, Chair Professor Peter A. Fritzsche Associate Professor Laurie R. Johnson Professor Carl Niekerk Associate Professor Yasemin Yildiz Abstract Scholars emphasize concepts of trauma and loss to describe literary responses to the collapse of socialism in 1989. In contrast, focusing on literary representations of family, this project reveals productive coping mechanisms developed in German literature after 1989. In artistic representation, family marks the site where the GDR’s dissolution and new post-1989 beginnings are negotiated. I draw on the concepts of agency, memory, and space to show how the historical transformation in 1989 affected existing family structures and how narrative family representations negotiate the historical meaning of 1989. Situated at the intersection of literature, cultural studies, and history, this project shows how family representations constitute a privileged site of post-socialist renewals. ii Für meine Eltern, Ingrid und Peter Kroh, deren Leitspruch “Die Familie ist immer das Wichtigste.” sich sowohl während als auch in dieser Arbeit bewahrheitet hat. iii Acknowledgements I am fortunate to have been supported by many people and institutions working on this study. I want to thank the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures as well as the School of Literatures, Cultures & Linguistics at the University of Illinois and the Max Kade Foundation for providing generous founding over the past years, which has allowed me to focus exclusively on my research and writing for an extended period of time. -

What's Left of the Left: Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging

What’s Left of the Left What’s Left of the Left Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging Times Edited by James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Duke University Press Durham and London 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: The New World of the Center-Left 1 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Part I: Ideas, Projects, and Electoral Realities Social Democracy’s Past and Potential Future 29 Sheri Berman Historical Decline or Change of Scale? 50 The Electoral Dynamics of European Social Democratic Parties, 1950–2009 Gerassimos Moschonas Part II: Varieties of Social Democracy and Liberalism Once Again a Model: 89 Nordic Social Democracy in a Globalized World Jonas Pontusson Embracing Markets, Bonding with America, Trying to Do Good: 116 The Ironies of New Labour James Cronin Reluctantly Center- Left? 141 The French Case Arthur Goldhammer and George Ross The Evolving Democratic Coalition: 162 Prospects and Problems Ruy Teixeira Party Politics and the American Welfare State 188 Christopher Howard Grappling with Globalization: 210 The Democratic Party’s Struggles over International Market Integration James Shoch Part III: New Risks, New Challenges, New Possibilities European Center- Left Parties and New Social Risks: 241 Facing Up to New Policy Challenges Jane Jenson Immigration and the European Left 265 Sofía A. Pérez The Central and Eastern European Left: 290 A Political Family under Construction Jean- Michel De Waele and Sorina Soare European Center- Lefts and the Mazes of European Integration 319 George Ross Conclusion: Progressive Politics in Tough Times 343 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Bibliography 363 About the Contributors 395 Index 399 Acknowledgments The editors of this book have a long and interconnected history, and the book itself has been long in the making.