Pack Monadnock Raptor Observatory Fall 2020 Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Town of Temple, New Hampshire Planning Board

TOWN OF TEMPLE, NEW HAMPSHIRE PLANNING BOARD NOVEMBER 30, 2011 FINAL MINUTES OF PUBLIC MEETING Board members present: John Kieley, Randy Martin, Bruce Kullgren, Allan Pickman, Richard Whitcomb, and Rose Lowry Call to order by Pickman at 7:20 p.m. after a slight delay in setting up the PowerPoint presentation. Public forum on Large Wind Energy Systems: Lowry welcomed the audience of approximately 60 people and gave an overview of the meeting format. She asked that questions be held until after the initial presentation. Lowry then provided commentary to a PowerPoint display. She explained that Pioneer Green Energy has proposed a multi-tower wind farm project in the neighboring town of New Ipswich, and is also considering placement of 1 to 3 towers in Temple in the area of Kidder Mountain. She indicated planning is still in the preliminary stages. She said Temple is considered an abutter to the New Ipswich project due to regional impact. Even if no turbines are installed in Temple, all New Ipswich towers would be visible in Temple. Lowry stated New Ipswich already has a large wind energy zoning ordinance in place to regulate commercial wind, and now Temple is considering creation of such an ordinance. This would help maintain local control, protect the character of the town, safeguard public health and safety, preserve property values, and protect wildlife and the environment. She also said without any local control the state Site Evaluation Committee (SEC) could become involved, as well as the local Zoning Board of Adjustment (ZBA). Lowry next discussed turbine size and the amount of energy created. -

Agency Real Property Reports Required by Rsa 4

STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE AGENCY REAL PROPERTY REPORTS REQUIRED BY RSA 4:39-e FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2019 4:39-e Real Property Owned or Leased by State Agencies; Reporting Requirement. I. On or before July 1, 2013, and biennially thereafter, each state agency, as defined in RSA 21-G:5, III, shall make a report identifying all real property owned or leased by the agency. For each parcel owned by the agency, the report shall include any reversion provisions, conservation or other easements, lease arrangements with third parties, and any other agreement that may affect the future sale of the property. For each parcel leased by the agency, the report shall include the lease term. II. Each state agency shall file the report with the governor, the senate president, the speaker of the house of representatives, the chairperson of the senate capital budget committee, the chairperson of the house public works and highways committee, the chairperson of the long range capital planning and utilization committee established in RSA 17-M:1, and the commissioner of the department of administrative services. III. The commissioner of the department of administrative services shall develop a standard format for agencies to use in submitting the report required under this section. The form of the report shall not be considered a rule subject to the provisions of RSA 541-A. (Source. 2012, 254:1, eff. June 18, 2012.) Introduction and Notes In developing a standard format for all agencies to use in submitting the report required by RSA 4:39-e, Administrative Services (DAS) staff designed and constructed a central state real property database to receive, store, maintain and manage information on all real property assets owned or leased by the State of New Hampshire, and from which all agency reports are generated. -

Hike Leader Handbook

Excursions Committee New Hampshire Chapter Of the Appalachian Mountain Club Hike Leader Handbook February, 2016 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 2 of 75. 2AMC–NH Chapter Excursions Committee Hike Leader Handbook Table of Contents Letter to New Graduates The Trail to Leadership – Part D Part 1 - Leader Requirements Part 2 – Hike Leader Bill of Rights Part 2a-Leader-Participant Communication Part 3 - Guidelines for Hike Leaders Part 4 - Hike Submission Procedures Part 5 – On-line Hike Entry Instructions (AMC Database) Part 5a – Meetup Posting Instructions Part 6 – Accident & Summary of Use Report Overview Part 7 - AMC Incident Report Form Part 8 - WMNF Use Report Form Part 9 - Excursions Committee Meetings Part 10 - Mentor Program Overview Part 11 – Leader Candidate Requirements Part 12 - Mentor Requirements Part 13 - Mentor Evaluation Form Part 14 - Class 1 & 2 Peaks List Part 15 - Class 3 Peaks List Part 16 - Liability Release Form Instructions Part 17 - Release Form FAQs Part 18 - Release Form Part 19 - Activity Finance Policy Part 20 - Yahoo Group Part 21 – Leadership Recognition Part 22 – Crosswalk between Classes and Committees NH AMC Excursion Committee Bylaws Page 1 of 2 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 3 of 75. Page 2 of 2 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 4 of 75. Hello, Leadership Class Graduate! We hope that you enjoyed yourself at the workshop, and found the weekend worthwhile. We also hope that you will consider becoming a NH Chapter AMC Hike leader—you’ll be a welcome addition to our roster of leaders, and will have a fun and rewarding experience to boot! About the Excursions Committee: We are the hikers in the New Hampshire Chapter, and we also lead some cycling hikes. -

New Hampshirestate Parks M New Hampshire State Parks M

New Hampshire State Parks Map Parks State State Parks State Magic of NH Experience theExperience nhstateparks.org nhstateparks.org Experience theExperience Magic of NH State Parks State State Parks Map Parks State New Hampshire nhstateparks.org A Mountain Great North Woods Region 19. Franconia Notch State Park 35. Governor Wentworth 50. Hannah Duston Memorial of 9 Franconia Notch Parkway, Franconia Historic Site Historic Site 1. Androscoggin Wayside Possibilities 823-8800 Rich in history and natural wonders; 56 Wentworth Farm Rd, Wolfeboro 271-3556 298 US Route 4 West, Boscawen 271-3556 The timeless and dramatic beauty of the 1607 Berlin Rd, Errol 538-6707 home of Cannon Mountain Aerial Tramway, Explore a pre-Revolutionary Northern Memorial commemorating the escape of Presidential Range and the Northeast’s highest Relax and picnic along the Androscoggin River Flume Gorge, and Old Man of the Mountain plantation. Hannah Duston, captured in 1697 during peak is yours to enjoy! Drive your own car or take a within Thirteen Mile Woods. Profile Plaza. the French & Indian War. comfortable, two-hour guided tour on the 36. Madison Boulder Natural Area , which includes an hour Mt. Washington Auto Road 2. Beaver Brook Falls Wayside 20. Lake Tarleton State Park 473 Boulder Rd, Madison 227-8745 51. Northwood Meadows State Park to explore the summit buildings and environment. 432 Route 145, Colebrook 538-6707 949 Route 25C, Piermont 227-8745 One of the largest glacial erratics in the world; Best of all, your entertaining guide will share the A hidden scenic gem with a beautiful waterfall Undeveloped park with beautiful views a National Natural Landmark. -

Birds of Mt. Philo State Park

Sp Su F W Sp Su F W __ Tree Swallow c u c - __ Magnolia Warbler c r c - Birds __ Barn Swallow u u u - __ Bay-breasted Warbler r - u - Chickadees and Titmice __ Blackburnian Warbler* c u c - __ Black-capped Chickadee* c c c c __ Chestnut-sided Warbler* c c c - of Mt. Philo __ Tufted Titmouse* c c c c __ Blackpoll Warbler u - c - Nuthatches __ Black-throated Blue Warbler* c c c - State Park __ Red-breasted Nuthatch* u u u r __ Pine Warbler* u u u - __ White-breasted Nuthatch* c c c c __ Yellow-rumped Warbler c r c - M Creepers __ Black-throated Green Warbler c r c - t __ Brown Creeper* u u u u __ Canada Warbler* u r u - . Wrens Sparrows P __ Winter Wren* c c c - __ Eastern Towhee* c c c - h Kinglets __ Chipping Sparrow* c c c - i __ Golden-crowned Kinglet c - c - __ Field Sparrow r r r - l __ Ruby-crowned Kinglet c - c - __ Savannah Sparrow r r r - o Thrushes __ Song Sparrow* c c c - S __ Veery* c c c - __ White-throated Sparrow c - c - t __ Swainson's Thrush u - u - __ Dark-eyed Junco* u u u - a __ Hermit Thrush* c c c - Cardinals and Relatives t e __ Wood Thrush* c c c - __ Scarlet Tanager* c c c - __ American Robin* c c c r __ Northern Cardinal* c c c c P Waxwings __ Rose-breasted Grosbeak* c c c - a __ Bohemian Waxwing r - - r __ Indigo Bunting* u u u - r Mt. -

State of New Hampshire

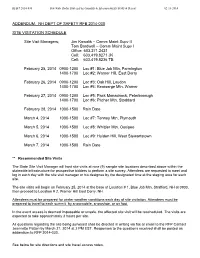

RFB # 2014-030 Statewide Radio System Functionality & Interoperability Study & Report 02-10-2014 ADDENDUM. NH DEPT OF SAFETY RFB 2014-030 SITE VISITATION SCHEDULE Site Visit Managers; Jim Kowalik – Comm Maint Supv II Tom Bardwell – Comm Maint Supv I Office: 603.271.2421 Cell: 603.419.8271 JK Cell: 603.419.8236 TB February 25, 2014 0900-1200 Loc #1: Blue Job Mtn, Farmington 1400-1700 Loc #2: Warner Hill, East Derry February 26, 2014 0900-1200 Loc #3: Oak Hill, Loudon 1400-1700 Loc #4: Kearsarge Mtn, Warner February 27, 2014 0900-1200 Loc #5: Pack Monadnock, Peterborough 1400-1700 Loc #6: Pitcher Mtn, Stoddard February 28, 2014 1000-1500 Rain Date March 4, 2014 1000-1500 Loc #7: Tenney Mtn, Plymouth March 5, 2014 1000-1500 Loc #8: Whittier Mtn, Ossipee March 6, 2014 1000-1500 Loc #9: Holden Hill, West Stewartstown March 7, 2014 1000-1500 Rain Date ** Recommended Site Visits The State Site Visit Manager will host site visits at nine (9) sample site locations described above within the statewide infrastructure for prospective bidders to perform a site survey. Attendees are requested to meet and log in each day with the site visit manager or his designee by the designated time at the staging area for each site. The site visits will begin on February 25, 2014 at the base of Location # 1, Blue Job Mtn, Strafford, NH at 0900, then proceed to Location # 2, Warner Hill East Derry, NH. Attendees must be prepared for winter weather conditions each day of site visitation. Attendees must be prepared to travel to each summit by snowmobile, snowshoe, or on foot. -

December 15, 2020, Volume 18, Number 12 Member Spotlight

MassLand E-News The Newsletter of the Massachusetts Land Conservation Community December 15, 2020, Volume 18, Number 12 Member Spotlight Saving an Iconic Landscape North County Land Trust has a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to protect 200 acres including the south peak of Mt. Watatic. Mt. Watatic is a 1,832-foot monadnock just south of the Massachusetts– New Hampshire border, at the southern end of the Wapack Range of mountains. It lies within Ashburnham and Ashby, in Massachusetts, and New Ipswich in New Hampshire. It’s the terminus for the 22-mile Wapack Trail (heading north into NH) and the 92-mile Midstate Trail (heading south to CT). This parcel is part of a quilt of iconic landscapes and provides a critical addition to an unfragmented block of natural habitat. It would complete preservation of the entire summit of the popular Mt. Watatic. NCLT is working in partnership with the Department Fish and Game, as this property has been on the region’s radar as a key property of conservation interest for decades due to its high conservation and recreational value. Learn more. Or contact NCLT with questions at [email protected] or 978-466-3900. Here's your opportunity to highlight a project in the works, or a current conservation success story! Send a short description and a photo to [email protected]. We'd like to highlight properties in various parts of the state, so if we don't get to you this month, we will soon. If you'd like to support MLTC's efforts to educate, connect, and advocate for the Massachusetts land conservation community, please consider making a monthly or one-time tax-deductible donation Thank you! Donate MassLand News What a pleasure to join Groundwork Lawrence in November for a tour of the Ferrous Site, a beautiful 7.5 acre woodland and meadow created on post-industrial land at the historic and scenic confluence of Lawrence's North Canal and the Spicket and Merrimack Rivers. -

2021-22 LRTA M&G Guideside Final Lo-Res (5-27-21).Indd

www.lakesregion.org 800-60-LAKES www.lakesregion.org 800-60-LAKES MEREDITH BAY ROBERT KOZLOW ROBERT n n n n n n EVP MARKETING and more than 260 other beautiful lakes & ponds! & lakes beautiful other 260 than more and PURITY SPRING RESORT SPRING PURITY Kezar Lake Lake Kezar Lake Highland Ossipee Lake Lake Ossipee n n Lake Winnisquam Lake Opechee Lake Newfound Lake Lake Newfound n n Squam Lake Lake Squam Lake Sunapee Lake Lake Winnipesaukee Winnipesaukee Lake n n WILL BE BE WILL VACATION VACATION LRTA FREE! FREE! OMOT New Hampshire New New Hampshire New of of LAKES REGION LAKES REGION LAKES Map & Guide & Map Guide & Map O F F I C I A L A I C I F F O L A I C I F F O OMOT NHBM Marinas & Boat Rentals E-3 Vacation Home Rentals OTHER EVENTS Popular Hikes for E-4 Families of all Ages E-4 Country Inns G-4 D-3 Shopping E-3 Attractions D-3 D-3 Lake House at E-3 Ferry Point B&B G-6 Healthcare D-3 E-2 E-3 E-4 E-4 Lakes Region Tour Dining E-3 F-3 Spas E-4, E-3, E-3 D-2 State Parks and Swimming Areas D-3 D-4 E-4 E-3 Camping E-2 B-2 n HOLIDAY ACTIVITIES Hotels and Resorts n D-3 Annual Events Christmas at the Castle E-4 Accommodations n n Cabins, Cottages, Golf n Condos and Motels BOAT SHOWS n The Gift of Lights n C-4 E-3 n C-3 E-4 And almost 300 Candlelight Christmas Tours at crystal clear lakes and ponds! ARTS & CRAFTS FAIRS and FESTIVALS Canterbury Shaker Village E-4 C-4 G-3 D-2 C-2 C-2 C-2 D-2 G-3 E-4 C-4 FESTIVALS and FAIRS CRAFTS & ARTS Canterbury Shaker Village Village Shaker Canterbury crystal clear lakes and ponds! and lakes clear crystal Candlelight -

Hellcat Boardwalk Trail Replacement Gets the Greenlight! by Matt Poole, Visitor Services Manager

United States Fish & Wildlife Service Summer/Fall, 2019 Hellcat Boardwalk Trail Replacement Gets the Greenlight! by Matt Poole, Visitor Services Manager I always describe the Hellcat Trail Boardwalk as the most valuable and most loved “piece of visitor ser- vices infrastructure” at Parker River National Wild- life Refuge. Hellcat is where LOTS of refuge visitors, from across a broad range of user groups, have been going to observe wildlife in natural habitats for al- most 50 years! The venerable foot path is also a place where one can go simply to enjoy and connect with the rhythms of the natural world. The current boardwalk was built by high school-age, Youth Conservation Corps workers over the course of a handful of summers, beginning in the early 1970s. In its nearly half century of public service, Hellcat has never experienced a major facelift or Photo: Matt Poole/FWS overhaul. I always marvel that the original pressure The new Hellcat Boardwalk Trail will be completely wheel- treated lumber out there continues to support ref- chair accessible. uge visitors’ wildlife and nature experiences all these years later. As I always say, that old lumber “doesn’t owe anyone anything!” Just imagine this: In This Issue... It’s literally possible, if not probable, that someone Hellcat Boardwalk Replacement Gets Greenlight .......... 1 who, as a child, scrambled along the Hellcat board- walk back in 1972 has, in 2019, chased their own Restoring the Lower Peverly Pond Dam ......................... 3 grandchild down that very same stretch of board- Making Watershed Connections Personal ..................... 5 walk! But, nothing lasts forever… Exploring Wapack National Wildlife Refuge .................. -

Fall 1997 Vol. 16 No. 3

NevnHomprhire Bird Records Foll | 997 Vol. | 6, No. 3 Fromrhe Ediror We are pleased to honor Kimball Elkins in this issue of New Hampshire Bird Records. Kimball was the Fall Editor for many years and later served as Technical Editor until his death in Septemberof L997. All of us will miss Kimball, who was not only a valuable resourceon birds in the statebut also a wonderful person. A special thank you to SusanFogleman for the cover illustration of a Barred Owl which originally appearedinlhe Atlas of Breeding Birds in New Hampshire. Susan's artworkmaybefoundthroughoutthisissueofNewHampshireBirdRecordsinmemory of Kimball Elkin's friendship and mentoring. We appreciate the support of the donors who sponsoredthis issue in Kimball's memory. Donations may also be made in Kimball's honor to a fund for the revision of his Checklist of the Birds of New Hampshire. Pleasecontact me at 224-9909 for more information. BeclcySuomala Managing Editor New HampshirizBird Records (NHBR) is published quarterly by the Audubon Society of New Hampshire (ASNH). Bird sightings are submitted to ASNH and are edited for publication. A computerized printout of all sightings in a seasonis available for a fee. To order a printout, purchaseback issues,or volunteer your observationsfor NfIBR, please contact the Managing Editor at224-9909. We are always interested in receiving sponsorshipfor NH Bird Records. If you or a company/organization you work for would be interested, pleasecontact Becky Suomalaat224-9909. Published by rhe Audubon Society of New Hompshire New Hampshire Bird Records @ ASNH 1998 \!rd^@^ Printedon RecycledPaper Dedicofion Kimball Elkins, a long-time editor of New Hampshire Bird Records, loved birds and birding. -

GRANIT 7.5' Quad Tile Index 1 2 3

GRANIT 7.5' Quad Tile Index 1 2 3 1 GREELEY BROOK 108 DANBURY 4 5 6 7 2 PROSPECT HILL 109 BRISTOL PITTSBURG 3 MOOSE BOG 110 WINNISQUAM LAKE 4 METALLAK MOUNTAIN 111 LACONIA 5 COWEN HILL 112 WEST ALTON 6 SECOND CONNECTICUT LAKE 113 WOLFEBORO 8 9 10 11 7 RUMP MTN 114 SANBORNVILLE 8 PITTSBURG 115 GREAT EAST LAKE CLARKSVILLE ATKINSON & 9 LAKE FRANCIS 116 WINDSOR GILMANTON 10 MAGALLOWAY MOUNTAIN 117 CLAREMONT NORTH 11 BOSEBUCK MTN 118 GRANTHAM STEWARTSTOWN 12 13 14 15T SECOND 16 12 MONADNOCK MTN, VT-NH 119 SUNAPEE LAKE NORTH N A COLLEGE R G GRANT 13 LOVERING MOUNTAIN 120 NEW LONDON COLEBROOK S ' X DIXVILLE I 14 DIAMOND POND 121 ANDOVER D 15 MOUNT PISGAH 122 FRANKLIN 16 WILSONS MILLS 123 NORTHFIELD WENTWORTHS COLUMBIA LOCATION 17 BLOOMFIELD 124 BELMONT 17 18 1ER9VINGS 20 21 22 18 TINKERVILLE 125 GILMANTON IRON WORKS LOCATION 19 BLUE MOUNTAIN 126 ALTON MILLSFIELD ERROL 20 DIXVILLE NOTCH 127 FARMINGTON 21 ERROL 128 MILTON ODELL 22 UMBAGOG LAKE NORTH 129 SPRINGFIELD STRATFORD 23 MAIDSTONE LAKE 130 CLAREMONT SOUTH 23 24 25 26 27 28 DUMMER 24 STRATFORD 131 NEWPORT CAMBRIDGE 25 PERCY PEAKS 132 SUNAPEE LAKES D N A 26 DUMMER PONDS 133 BRADFORD L R E B 27 TEAKETTLE RIDGE 134 WARNER M STARK U H 28 UMBAGOG LAKE SOUTH 135 WEBSTER T MILAN R 29 O 30 31 32 33 29 GROVETON 136 PENACOOK N 30 STARK 137 LOUDON Y 31 WEST MILAN 138 PITTSFIELD N N E K BERLIN SUCCESS L 32 MILAN 139 PARKER MOUNTAIN I LANCASTER K 33 SUCCESS POND 140 BAXTER LAKE 34 MILES POND 141 ROCHESTER 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 35 LANCASTER W 142 SOMERSWORTH GORHAM RANDOLPH D A L T O N JEFFERSON 36 LANCASTER E 143 BELLOWS FALLS SHELBURNE 37 PLINY RANGE W 144 ALSTEAD WHITEFIELD 38 PLINY RANGE E 145 EAST LEMPSTER MARTINS 39 BERLIN 146 WASHINGTON LITTLETON CARROLL LOW & LOCATION & . -

Mount Watatic Reservation RMP

Mount Watatic Reservation RMP Mount Watatic Reservation – Resource Management Plan References Ashburnham, Massachusetts. Open Space and Recreation Plan, 2004-2009. Ashby, Massachusetts. Open Space and Recreation Plan, 1999-2004. Clark, Frances (Carex Associates), 1999. Biological Survey of Mt. Watatic Wildlife Management Area and Vicinity. Prepared for Mass. Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Division of Conservation Services. 2000. Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan. Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program. 2001. Biomap: Guiding Land Conservation for Biodiversity in Massachusetts. Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program. 2003. Living Waters: Guiding the Protection of Freshwater Biodiversity in Massachusetts. Executive Office of Environmental Affairs, Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program. 2004. Species Data and Community Stewardship Information. Grifith, G.E., J.M. Omernik, S.M. Pierson, and C.W. Kiilsgaard. 1994. The Massachusetts Ecological Regions Project. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Publication No.17587-74-6/94-DEP. Johnson, Stephen F. 1995. Ninnuock (The People), The Algonquin People of New England. Bliss Publishing, Marlborough, Mass. Massachusetts Invasive Plant Advisory Group. 2005. Strategic Recommendations for Managing Invasive Plants in Massachusetts.